Franciszek Ptak

Franciszek Ptak (30 August 1859 – 29 July 1936) was a Polish peasant, innkeeper, politician and publisher active in the peasant movement, who was a member of the Diet of Galicia and Lodomeria between 1908–1913.

Franciszek Ptak | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 30 August 1859 |

| Died | 29 July 1936 (aged 76) |

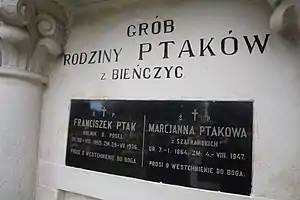

| Resting place | Raciborowice Parish Cemetery Raciborowice, Poland |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Occupation |

|

| Political party | Polish People's Party "Left", Polish People's Party "Piast" |

| Spouse(s) | Marcjanna Szafrańska

(m. 1886; |

He ran an inn in the village of Bieńczyce, on the outskirts of Kraków. Reportedly, the inn prospered, thanks to Ptak's entrepreneurship, outmatching the competitive Jewish innkeeper.

Ptak began his political activity in the 1890s. He published peasant magazines, that he distributed in his inn, and became a member of the Polish People's Party (PSL). He held various positions in the PSL local structures, and ran for the deputy of the Diet of Galicia and Lodomeria several times. He succeeded in 1908, when he was elected a representative of the rural communes of the Kraków poviat.

His lack of success in the elections to the Austrian Imperial Council some years earlier was mentioned in the plot of The Wedding by Stanisław Wyspiański (1901), in one of the dialogues: So it's Ptak that you were taking on the position?. According to Young Poland's notable literary critic Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński, Ptak was to some extent a model persona of Czepiec, one of the protagonists of The Wedding. Alongside his wife, Ptak was a special guest at the world premiere of The Wedding in the Kraków Municipal Theater.

From 1907, he was a member of the Supreme Council of the Polish People's Party. After the party split, he was a member of the Polish People's Party "Left" (1913–1924) and the Polish People's Party "Piast" (1924–1931). He co-financed the construction of the "Falcon" Polish Gymnastic Society House and the public school in his native village Bieńczyce, as well as in the construction of the Bonifratres Hospital in Kraków, and was friends with several artists, among them Włodzimierz Tetmajer.

Ptak was known for his defiant character, great posture and pomp. Wincenty Witos recalled that Ptak was “a man with a face full of pride, contentment, self-confidence and disrespect for the people who surrounded him”, and that he was disliked by the neighbouring peasants, who were “unable to endure the boasting parvenu”.

Biography

Early years

He was born to a peasant family, the son of Antoni Ptak, who owned seven acres, and Salomea née Włodek.[1] The family name Ptak means a bird in Polish.

Franciszek Ptak graduated from a peasant elementary school and was also a self-taught; he read a lot. He started with farming on his three acres. Periodically he was a wage worker in a mill. For nine years he charged a toll tax on the behalf of local authorities. In 1886 he married Marcjanna née Szafrańska (7 January 1864 – 4 August 1947). They had twelve children: five sons and seven daughters.[1]

Innkeeper

He founded and ran an inn in the village Bieńczyce outside Kraków. As an innkeeper, he always took care of laying current editions of the folk press on the tables so that the guests could read them. Thanks to his own entrepreneurship and diligence he managed to outmatch the competitive Jewish innkeeper. He was a co-founder and editor of the magazines Wieniec (Wreath) and Pszczółka (Little Bee) that focused on rural issues. His farm was considered exemplary in the district. He promoted the latest achievements in farming and breeding.[1]

Wincenty Witos, a prominent politician of the Polish People's Party and later a prime minister of Poland, recalled Ptak in his memoir. Witos described, among others, the first time he met Ptak in 1895 in Bieńczyce. According to Witos, other peasants expressed unflattering judgements about Ptak, “unable to endure the boasting parvenu”. Witos, who served at the time in the Austro-Hungarian Army, moved with his troop to the fort in the village of Krzesławice, and one day he “learned from the peasants coming with the potatoes to the barracks that in the neighboring village of Bieńczyce there is a host and an innkeeper, Franciszek Ptak, who deals with politics and receives folk newspapers.”[2]

On the subsequent Sunday, which was a day off, Witos with a friend of his went to visit the tavern in Bieńczyce, as Witos recalled: “Already on the way we learned from the neighbor of Mr. Ptak, who went to the village, that Ptak is an extremely rich man, but also no less a speculator and flay-flint, that he earns money on masters and priests, and for that money he buys estates and lends usury, that peasants and laborers give him the last pennies, etc. stuff. He also said that Mr. Ptak, in addition to the tavern, has a large stone house, a steam mill, a few dozen acres of land, and yet he rents all tolls in the poviat, takes military and poviat supplies, not giving anyone a chance to earn a penny.”[2] This “seemingly talkative and jealous” neighbor peasant, as Witos remarked, also said “that the current rich man, Mr. Ptak, although he comes from the beggar family, is himself worse than many a count. He considers peasants nothing, he only goes in with the masters, he travels to Vienna and Lviv for exhibitions, takes over his daughters around the world and introduces them to the great masters.”[2] Finally, the peasant “expressed the hope that this Sodom would end, and God's punishment would not pass Mr. Ptak.” Witos commented that “although these details have discouraged him a bit and prejudiced him, he decided to go to the inn”, the more that he and his friend were only about fifty steps away from it.[2]

Then Witos goes on describing his first direct encounter with Franciszek Ptak. “Having entered a very large inn, we found there a crowd of workers sipping vodka and beer, smoking pipes and cigarettes, talking loudly to each other. At a separate table Mr. Ptak was sitting with only few older hosts. In front of them stood a large, yet unfinished glass of beer. We put ourselves in a corner, and started reading the paper Przyjaciel Ludu (Friend of the People), which just lay on the table in front of us, heavily crumpled and stained. Not to be thrown out of the inn, we ordered a small glass of beer. At one point Mr. Ptak got up and went to another table. I looked at him closer. He was a tall, upright, handsome man of good corpulence and posture, a perfect model for a painter, sculptor or even a poet. His face was full of pride, contentment, self-confidence and disrespect for the people who surrounded him. I tried to talk to him in vain, he pushed away the intervening waiter and did not even look at me. And no wonder. I did not belong to those who would impress him with their property or office, or those who would make him earn more. He did not recognize others. I remembered his neighbor's chatter and I could not refuse him right. Although I went out a bit resentful from Mr. Ptak's inn, I did not fail to go there every Sunday afternoon, to read a newspaper and drink a small glass of beer, this way saving myself from being thrown out the door. I did not try to communicate Mr. Ptak any more, he also did not turn to me, always having a more urgent engagement.”[2]

Beginnings in the people's movement

Ptak went to politics, becoming a member of the Polish People's Party (PSL). He was associated with the Christian-folk movement of priest Stanisław Stojałowski. In 1892, unsuccessfully he stood for the supplementary election to the Diet of Galicia and Lodomeria. From 1898 to 1902 he was an editor of the magazine Obrona Ludu (The Defend of the People) issued by the Stojałowski group in Kraków.[1]

Together with Witos, Ptak financially supported the construction of the Bonifratres Hospital at Trynitarska Street in Kraków. He was inscribed on the list of benefactors of the Order of Bonifratres. When he later did not want to stay in the hospital during his illness, the monks took care of him at home due to his services to the convent.

He also contributed to the construction of a brick school in Bieńczyce, the first of its kind in the poviat, and to the construction of a parish house in Raciborowice, next to the gothic fifteenth century church of St. Margaret.

Ptak was friends with several artists. Among them was Włodzimierz Tetmajer. The correspondence of the two was preserved. In one of his pastels, Włodzimierz Tetmajer depicted Ptak and other peasant Błażej Czepiec. Ptak, on the other hand, made his old house available to the painter Józef Krasnowolski, who found himself together with his family in a difficult financial situation. The guests in Ptak's house, apart from Tetmajer and Krasnowolski, included Stanisław Wyspiański, Lucjan Rydel, Henryk Uziembło and Wojciech Kossak.

The Wedding episode

In December 1900 Franciszek Ptak ran unsuccessfully to the Austrian Imperial Council. A reference to that event appeared in one of the dialogues of Stanisław Wyspiański play The Wedding (1901). According to Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński, a notable figure of the Young Poland, the fictional figure of Czepiec brought to life by Wyspiański was modeled mainly after Błażej Czepiec, a peasant from the village of Bronowice, but in fact included some characteristics of both Błażej Czepiec and Franciszek Ptak. Boy-Żeleński pointed out that “Wyspiański, portraying Czepiec in several authentic situations of that wedding reception, strengthened his physiognomy with some of the features taken from another sub-Krakow peasant, Ptak. Mr. Ptak, even taller than Czepiec, a peasant of enormous strength, popular in the poviat, magnificent in his white coat, a figurehead on all “national parades” (...) also did not let others to push him around; when some kind of intellectual tried to offend his honor, Ptak said only: – Beware, sir, because I am of the Ptaks that beat in the face”[3] (in Polish: of the Birds that beat in the face).

Wyspiański invited Mr. and Mrs. Ptak to the premiere show of The Wedding in the Kraków Municipal Theatre.[1] Author of the play was particularly interested in the opinion of Mrs. Marcjanna Ptak, whom he “valued for practical peasant reason”.[4] A columnist, literary critic and wife of the then-director of the Municipal Theatre Lucyna Kotarbińska recalled: “Wyspiański wanted to check what impression would The Wedding make on the countrywoman who doesn't have any closer contact with our artistic and literary world. We have agreed that, following his wishes, we will invite a peasant from Tonie, near Kraków, Mr. Ptak, with his wife. Mr. Ptak was a wise peasant. Deputy. Editor of the magazine. The only one eager to help to make decorations during ceremonies. Indeed he made the Jew move out from the tavern in the village, but he took the tavern himself, and his wife traded well at the canteen. Apart from that, she was also very strict. So we go to them, on Sunday afternoon, with our sister Teofila Kotarbińska, who was staying at our place, and Włodzimierz Tetmajer. The host welcomed us like Piast. In a white sukmana with a loaf of bread, putting a jar of honey, which we liked so much that we forgot about the hour. And here's the show and we have to get on the train we just hear whistling. We run as if we were shot from a sling, as if we all had wings, trotting through the fields, with waving hands, handkerchiefs and screams, that the train stands in the middle of nowhere and takes us to Kraków. Well, that's when we invited Mr. and Mrs. Ptak to the lodge, in which Mrs. Ptak was the main subject of our observation. She behaved quite indifferently to the whole. She only reacted to one thing, namely, when in response to a long epistle of The Poet, Czepiec says: – Take a simple wife: much bliss, little cost. – If someone takes a simple wife, the costs are smaller, it's true, but that it gives much bliss – I do not believe it, judged Mrs. Ptak.”[5]

Member of the Diet of Galicia and Lodomeria

Ptak collaborated with Jan Stapiński, a priest and co-organizer of the People's Party (SL) in Galicia.[1] In 1897–1909, as a representative of the rural communes, he was a member of the Poviat Council of the People's Party in Kraków and the deputy member of the Poviat Department in Kraków. From 1904 he was a member of the Poviat Department of the People's Party in Kraków. From 1904 to 1910 he was a member of the District School Council in Kraków on behalf of the Poviat Council of the People's Party. On January 20, 1907, he was elected a member of the Supreme Council of the Polish People's Party. He resigned from candidacy for the benefit of Franciszek Wójcik before the elections to the Austrian Imperial Council in May 1907.[1]

In 1908, Ptak organised together with Władysław Bogacki a sizable live show in Vienna, titled The Cracovian Wedding. The show has been performed to the eyes of the Emperor of Austria Franz Joseph I to celebrate the sixtieth anniversary of his accession to the Austrian throne.[1] Ptak's daughter Zofia Ptak played the part of a bride, the painter Henryk Uziembło performed as the groom, while Wojciech Kossak played the starost. The performance sparked enthusiasm in Vienna and echoed widely in Galicia, in the latter also resulting in a wave of harsh criticism. Stanisław Szczepański referred to Ptak as “Kraków paradebauer”,[1] pejoratively meaning a peasant or farmer making an empty and meaningless performance in a parade just for the sake of the government to avoid claims of excluding peasantry from the public life.[6]

On February 25, 1908 Ptak was elected a member of the Diet of Galicia and Lodomeria (Sejm Krajowy), representing the rural communes of the Kraków poviat. In the Diet, he was a member of the petition committee and the commune committee. From 1910 he was also a member of the dearness committee. He spoke, among others, on the abolition of the national toll (October 1, 1908) and the establishment of a school of rural housewives in the poviat of Kraków (October 14, 1909), and was also a parliamentary auditor. He and his fellow Members made an urgent proposal to prevent hunger threatening populations throughout the country (March 19, 1913).[1]

On March 8, 1908, Ptak was re-elected a member of the Supreme Council of the Polish People's Party.[1]

In 1909 he founded a branch of the “Falcon” Polish Gymnastic Society in his village Bieńczyce.[7] The “Falcon” House was built from the contributions of the residents of Bieńczyce on the plot given by Ptak. The construction work took place under his leadership and with his significant financial participation.

He was a member of the Supervisory Board of the National Central Fund for Agricultural Companies in Lviv (1913–1914).[1]

In the Polish People's Party "Left"

In the elections to the Diet of Galicia and Lodomeria on June 30, 1913, Ptak did not receive re-election, losing his mandate to the benefit of Józef Serczyk of the People's Party. Ptak was a member of the Polish People's Party Supreme Council during its meeting in Tarnów on December 13, 1913. At the meeting the party has split into the Polish People's Party "Left", which gathered supporters of Stapiński; and the Polish People's Party "Piast", led by Jakub Bojko and Wincenty Witos. Franciszek Ptak joined the Polish People's Party "Left" and was elected a member of its Supreme Council on April 5, 1914. On June 28, 1914, together with Franciszek Wójcik, he addressed the peasants with financial support for the Polish People's Party "Left".[8]

During World War I (1914–1918) Ptak did not serve in the army and remained at home. During the short-lived reunification of the Polish People's Party "Piast" and the Polish People's Party "Left", he was elected a member of the Central Board of the Polish People's Party at the congress in Tarnów on December 1, 1918.[1]

Wincety Witos in his memoir recalled a short conversation he had with Ptak in the spring of 1917. A resolution stating that the only pursuit of the Polish nation is to regain an independent, united Poland with access to the sea was then submitted to the Imperial Council in Vienna by Włodzimierz Tetmajer. Until then, territories of the former Polish Republic remained under foreign annexations, and ethnically Polish Galicia was a part of Austro-Hungary. Witos wrote: “In the evening, the Kraków peasants took up the deputy Tetmajer, proud of what had happened, satisfied with their chosen one. I saw Franciszek Ptak among them (...) and several others. Despite my will, I recalled all the galas and festivities in which they took part, appearing equally festive and having happy faces. The difference was that they were richly paid for imperial money there, and here they were the hosts. In a word, the Kraków peasants of that time were not the best. That's nothing surprising, however, because they were constantly demoralized, used for decorations and various decorative performances. They did not feel strong at that time, because when someone brought news that the police were to arrest the participants of the manifestation, they immediately remembered various urgent interests and began to leave alone. Franciszek Ptak, who was very defiant all the time, approached me and asked: – What do you think , Wicek, if Poland will rise, will it be a bit better for the peasants? Because I think that the governments of gentry and new serfdom will come. – Why do these thoughts come to you again? – I asked. – I know our masters – he said – they are taught to live through someone else's work and rush, and now they will be even worse, because they have less, and would like to use endlessly.”[9]

Witos also illustrated Ptak's parsimony with an episode that took place in the first months after the establishment of the Polish state, around 1919, when a Polish military detachment commandeered Ptak some oats. Poland was at the time in a war with the Soviet Union to the eastern border. “Mr. Ptak defended himself against giving away oats so much that they had to be overtaken by force. It resented and at the same time upset him so much that not only did he cover the soldiers with insults on the spot, but also in public.”[2]

In 1920 Ptak, outraged by the need to pay fines for not sending children to school, organized together with Franciszek Wójcik a meeting for about forty people and was to convince the gathered parents not to pay fines imposed by the District School Board. The School Board in the village of Krzesławice accused Ptak of anarchism. Ptak did not plead guilty, he replied, saying that he “did not announce that children should not be sent to school nor that the parents should not pay fines for not sending their children to school.” The case was discontinued.[10]

In the Polish People's Party "Piast" – the final years

In 1924, he left the Polish People's Party "Left" and joined the People's Party "Piast". In Bieńczyce he founded a branch of Kasa Stefczyka, a savings and loan cooperative created on the model of Raiffeisen cooperatives in several spots in Galicia, and served more than a dozen neighboring villages being a long-time president of the branch. In 1932, with the Banderia of Cracovians he welcomed Wincenty Witos who was going to nearby village of Pleszów.[1] Witos described this event as follows.

“Mr. Franciszek Ptak was this kind of person whose luck never leaves. His growth, beauty, and attitude were themselves simply an invaluable gift of God, which he did not waste at all. I did not know his origin, nor did I ever try to find out. On the other hand, the native serfs of Kraków, who knew him more closely, thought that he was nobody compared with them in this respect, and often maliciously told that it was Mr. Ptak that Wyspiański meant when writing about birds, eagles and shit. Maybe they did this out of envy, unable to endure the boasting parvenu. On the other hand, having gained a serious fortune, he threw himself into politics with panache and impudence typical for him, though he did not have much talent for it. Over the years, he passed almost all parties and tried to be their zealous follower. Not wanting to go against the trend, he even lost himself in the Socialist faction, and motivated a change of opinion saying that now the whole world is going to the left. (...) In spite of everything that happened, you can see that he did not lose his sentiment for me, because in 1932, when I was going to Pleszów through his village, not only did he, along with others, prepare a great honorary horse escort, but welcomed me very cordially, he did not fail to mention that he does so on the spot where Kościuszko rested, when he went to Racławice and expressed confidence that I would be given the completion of the work begun by Kościuszko and the assurance of freedom not only to Poland, but also to peasants who did not have it so far. I saw that he spoke honestly and powerfully, because the policeman, alarmed, had recorded his entire speech.”[2]

Franciszek Ptak died after long illness on July 29, 1936 at the Bonifratres Hospital in Kraków.[11] He was buried at the parish cemetery in Raciborowice three days later, on August 1.[1]

Family

Franciszek Ptak and Marcjanna née Szafrańska had twelve children: five sons and seven daughters. Among their grandchildren were Włodzimierz Ptak, an immunologist,[12] and Wiesław Ptak, a chemist.

Commemoration and cultural references

One of the streets in Kraków, in the district Bieńczyce, was named after Franciszek Ptak.[13]

A few souvenirs of Ptak have been preserved, including a wide leather belt, richly decorated and studded with brass studs. Natural-size oil portraits of Franciszek and Marcjanna Ptak by Józef Krasnowolski were put into a deposit of the Regional Chamber of Culture Center of the then Vladimir Lenin Steelworks in 1973 by Władysław Ptak, the son of Franciszek and Marcjanna. Currently, the portraits are owned by the C. K. Norwid Culture Centre in Kraków (Ośrodek Kultury im. Cypriana Kamila Norwida w Krakowie).

The old print depicting Franciszek Ptak is part of the decoration of the Eszeweria Café in Kraków at Józefa Street in the Jewish district Kazimierz.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Franciszek Ptak. |

- Korczyk, Henryk (1986). "Franciszek Ptak (1859–1936)". Polish Biographical Dictionary. XXIX/2. Polish Academy of Learning. pp. 287–288.

- Witos, Wincenty (1981). "Karczmarz z Bieńczyc". Moje wspomnienia. Ludowa Spółdzielnia Wydawnicza. pp. 177–179.

- Boy-Żeleński, Tadeusz (1963). "Zmarł Czepiec z Wesela". O Krakowie. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. p. 415.

- "Franciszek Ptak" (in Polish). nhpedia.pl. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- Kotarbińska, Lucyna (1930). Wokoło teatru. Moje wspomnienia. Warszawa: Księgarnia F. Hoesicka. pp. 202–203.

- Kopaliński, Władysław. Słownik wyrazów obcych i zwrotów obcojęzycznych.

- "Franciszek Ptak" (PDF) (in Polish). C. K. Norwid Culture Centre in Kraków. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- Przyjaciel Ludu, 26, 1914, p. 4.

- Witos, Wincenty (1981). Moje wspomnienia, p. 499.

- Drożdżak, Artur (16 September 2009). "Buntownik w oświacie". Gazeta Krakowska. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- "Zgon b. pos. Franciszka Ptaka". Ilustrowany Kuryer Codzienny. 212: 10. 1 August 1936.

- Kobos, Andrzej (2009). Po drogach uczonych. 4. Kraków: Polish Academy of Learning. pp. 383–398. ISBN 978-83-7676-021-6.

- "Alphabetical list of streets in Kraków" (PDF) (in Polish). iskrakow.krak.pl. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.