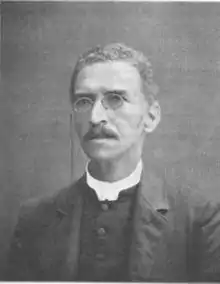

Francis James Grimké

Francis James Grimké[1] (October 10, 1850 – October 11, 1937) was an American Presbyterian minister in Washington, DC. He was regarded for more than half a century as one of the leading African-American clergy of his era[2] and was prominent in working for equal rights. He was active in the Niagara Movement and helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

Early life and education

Francis Grimké was the second of three sons born to Henry Grimké, a white (European-American) slaveholder of Charleston, South Carolina, and Nancy Weston, an enslaved woman of European and African descent. After becoming a widower, the senior Grimké began a relationship with Weston. He moved with her out of the city to his plantation where they and their family would have more privacy. She was his official domestic partner in the house. Both Henry and Nancy gave Francis and his brothers -- Archibald and John—their first lessons in reading and writing.

Henry Grimké had come from a large family. Among them were two sisters, Sarah and Angelina Grimké, who had become abolitionists and moved to the North to join activists there. His other siblings continued to represent and carry out the expected roles, as he mostly did, of their prominent slaveholding family of Charleston.

Discovery

Henry Grimké died in 1852. As he was dying, Henry tried to protect his second family by willing Nancy, who was pregnant with their third child, and their two sons Archibald and Francis to his son and heir Montague Grimké, by his first wife. He directed that they "be treated as members of the family."[3]

Henry's sister Eliza, executor of his will, brought the family to Charleston and allowed them to live as if they were free, but she did not aid them financially. Nancy Weston took in laundry and did other work; when the boys were old enough, they attended a public school with free blacks. In 1860 Montague "claimed them as slaves," bringing the boys into his home as servants.[3] Later he hired out both Archibald and Francis. During the American Civil War, Francis ran off and became a valet for a Confederate Army Officer stationed at Castle Pinckney, a jail for Union soldiers. Francis was found and jailed for a time before being returned to Montague Grimké, who sold him to another Confederate officer.[4] Archibald ran away and hid for two years with relatives until after the end of the Civil War.[5] Montague never provided well for his half-brothers or for their mother.

After the American Civil War ended, the three Grimké boys attended freedmen's schools, where their talents were recognized by the teachers. They gained support to send Archibald and Francis to the North. They studied at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, established for the education of blacks.[3]

Francis and his brother went through many hardships afterward, as their father had not provided for them financially. After the Civil War, which disrupted family fortunes further, Francis and Archibald were enrolled at Morris Street school, part of the Charleston public schools, a segregated system set up for the first time during the Reconstruction Era by a Republican-dominated, biracial legislature. Frank then went North to Stoneham, Massachusetts where he first stayed with a Dr. John Brown, and then with a Mr. and Mrs. Lyman Dyke. The brothers were then sponsored by Mrs. Pillsbury, sister-in-law of Parker Pillsbury, for higher education at Lincoln University. It was a historically black college founded in Pennsylvania for the education of blacks. They received tuition from a church committee, but had no money for books and clothing.[4]

In 1868, Angelina Grimké noted Archibald Grimké's surname in The Anti-Slavery Standard, after a speech of his was reported. Because of the unusual name, she wrote to learn whether he was related to her family. After learning that he was their nephew and about his brothers, Angelina and Sarah officially acknowledged the three mixed-race boys as family. The sisters supported the three boys while they were in college, and opened their home to them. The youngest brother, John Grimké, did not take to education and chose to stay in Charleston with their mother Nancy Weston.

Francis and Archibald both graduated from Lincoln University in 1870. Francis went on to graduate studies at Princeton Theological Seminary, from which he graduated in 1878.[6] Grimké became ordained as a Presbyterian minister.

Marriage and family

In December 1878, Grimké married Charlotte Forten, an abolitionist, teacher, and diarist. Charlotte was the granddaughter of James Forten, a prominent member of the free black elite of Philadelphia. Among her acquaintances were many members of the national abolitionist movement, including William Lloyd Garrison, Sarah Parker Remond, John Whittier, and Wendell Phillips. Charlotte was 41 and Francis was about 13 years her junior when they married. In 1880, they had one daughter, Theodora Cornelia, who died as an infant.

Career

Grimké began his ministry at the prominent 15th Street Presbyterian Church in Logan Circle, Washington, D.C., a major African-American congregation. He led that congregation until 1885, and was active throughout the community in Washington. He then moved to Woodlawn Presbyterian Church in Jacksonville, Florida in November 1886,[4] but in January 1889, returned to his former charge.

His elder brother Archibald was appointed as consul to the Dominican Republic from 1894 to 1898. During that time, Archibald's daughter Angelina Weld Grimké stayed with Grimké and his wife. Angelina later became a teacher, and a prominent writer and activist in her own right.

Francis was a participant in the March 5, 1897 meeting to celebrate the memory of Frederick Douglass which founded the American Negro Academy led by Alexander Crummell.[7] He became the organization's founding Treasurer, serving in this capacity until 1919. He played an active role among the scholars, editors, and activists of this first major African American learned society, which refuted racist scholarship, promoted black claims to individual, social, and political equality, and studied the history and sociology of African American life.[8]

Except for a few years' sojourn at Laura St. Presbyterian Church (now known as Woodlawn Presbyterian Church) in Jacksonville, Florida, Grimké continued to lead the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church in Washington, D.C. until 1928. He died in 1937, more than twenty years after Charlotte.

Francis Grimké said: "Race prejudice can't be talked down, it must be lived down."[9]

References

- Anyabwile, Thabiti (2007). The Faithful Preacher: Recapturing the Vision of Three Pioneering African-American Pastors. Crossway. ISBN 9781433519246. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- The Editors (November 22, 2013). "Francis Grimke: An African American Witness in Reformed Political Theology". Political Theology. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- Diedrich, Maria I. "Review: Lift Up Thy Voice:: The Grimké Family's Journey From Slaveholders to Civil Rights Leaders by Mark Perry", New York Times (December 2, 2001) Accessed: May 5, 2012

- Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. GM Rewell & Company, 1887. p608-612

- Botsch, Carol Sears (February 18, 1997). "Archibald Grimke". University of South Carolina-Aiken. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 15, 2008.

- Culp, Daniel Wallace (1902). Twentieth century Negro literature; or, A cyclopedia of thought on the vital topics relating to the American Negro. Atlanta: J.L. Nichols & Co. p. 426.

- Seraile, William. Bruce Grit: The Black Nationalist Writings of John Edward Bruce. Univ. of Tennessee Press, 2003. p110-111

- Alfred A. Moss. The American Negro Academy: Voice of the Talented Tenth. Louisiana State University Press, 1981.

- The Works of Francis J. Grimké, vol III, p. 323. Edited by Carter G. Woodson. The Associated Publishers, Inc. 1942

Bibliography

- Carol Sears Botsch (February 18, 1997). "Archibald Grimke". The University of South Carolina-Aiken. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- Mark R. Bradshaw-Miller (February 20, 2005). "The Life and Witness of Reverend Francis Grimke". Westminster Presbyterian Church. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- Thomas, Rhondda R. & Ashton, Susanna, eds. (2014). The South Carolina Roots of African American Thought, Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. "Francis Grimke (1850-1937)," p. 117-121.

- Woodson, Carter, ed. (1942). The Works of Francis J. Grimké. Three volumes. Washington, D.C.: The Associated Publishers, Inc.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Francis James Grimké |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Francis James Grimke. |

- Works by Francis James Grimké at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Francis James Grimké at Internet Archive

- Francis J. Grimke at the African American Registry

- Quotes