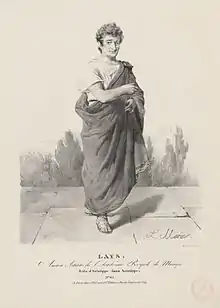

François Lays

François Lay, better known under the stage name Lays [1] (14 February 1758 – 30 March 1831[2]), was a French baritone and tenor opera singer. Originally destined for a career in the church, Lays was recruited by the Paris Opéra in 1779. He soon became a leading member of the company, in spite of quarrels with the management. Lays enthusiastically welcomed the French Revolution and became involved in politics with the encouragement of his friend Bertrand Barère. Barère's downfall led to Lays being imprisoned briefly, but he soon won back the public and secured the patronage of Napoleon, at whose coronation and second wedding he sang. This association with the Emperor caused him trouble when the Bourbon monarchy was restored and Lays's final years were darkened by disputes over his pension, mounting debts, the death of his only son and his wife's illness. After a career spanning more than four decades, he died in poverty.

Lays was famous for the beauty of his voice. One of the Opéra's most popular artistes, he enjoyed his greatest success singing comic roles, such as Anacreon in Grétry's Anacréon chez Polycrate (1797) and the bailiff in Lebrun's Le rossignol (1816).

Biography

Youth and education

Lays was born in the village of La Barthe-de-Neste in the region of Bigorre in what was then Gascony. His family intended him for a career in the Church at the Sanctuary of Notre-Dame-de-Garaison (Monléon-Magnoac), where he stayed until he was 17, receiving a solid musical education as a chorister and developing a remarkable baritenor voice. He was transferred to Auch for a short while to study philosophy and work as a teacher before returning to Garaison to study theology.[3] In 1778, the canons of the convent gave Lays a grant to study for a doctorate in theology in Toulouse. Lays was now determined to abandon a career in the Church and became increasingly active as a singer, joining the cathedral choir and accepting invitations to perform at local salons. In Toulouse, Lays formed a lifelong friendship with the young lawyer Bertrand Barère, the future French Revolutionary politician and member of the Committee of Public Safety. Barère introduced Lays to the city's Enlightenment circles. On Easter Sunday 1779, Lays was singing the liturgy in the cathedral when he was heard by the Intendant Royal of Languedoc. Following the recruitment practice then used by Académie Royale de Musique (the Paris Opéra), the Intendant decided to issue Lays with a royal ordinance (equivalent to a lettre de cachet) obliging him to travel to Paris for an audition.[4]

Early career

Lays was immediately enrolled in the company as one of the lower male voices (known in France at the time as basse-tailles) and began a rapid ascent up the Opéra career ladder. He was first introduced to the Parisian public on 10 October 1779, singing the aria "Sous les lois de l'hymen" by Pierre Montan Berton to great applause (it had been inserted into the acte de ballet La Provençale by Jean-Joseph Mouret and Pierre-Joseph Candeille[5]). He made his official debut on the 31st of the same month, playing Théophile in a revival of "Théodore", the second entrée from Étienne-Joseph Floquet's L'union de l'amour et des arts.[6] Having stepped in as a substitute in the role of Oreste in Gluck's Iphigénie en Tauride,[7] in 1780 he was given the first new roles of his career: a follower of Morpheus in Piccinni's Atys; the male protagonist in the unsuccessful acte de ballet Laure et Pétrarque by Candeille;[8] and the bailiff in Floquet's Le seigneur bienfaisant, Lays's first big success.[9] Between 1780 and 1791, he was a member of two of the main musical institutions at court, the Concerts de la reine (the Queen's concerts)[3] and the King's Grand Couvert,[10] soon becoming a favourite of the royal couple, and in particular of Marie Antoinette.[11]

His early career at the Opéra was quite turbulent. The institution at the time was seething with discontent: the artistes resented the fact their wages were only a third of those of the actors of the Comédie-Française and the Comédie-Italienne; moreover, their pay was only partly fixed and permanent, the rest being linked to how frequently they appeared on stage and the size of their roles. The rebellious Lays soon became embroiled in a heated confrontation with the management, behaving almost like a modern union agitator, with the support of two singers who had joined the company around the same time, the haute-contre Jean-Joseph Rousseau[12] and the bass Auguste-Athanase Chéron (1760–1829). In June 1781, fire destroyed the second hall of the Palais Royal, the home of the theatre, causing performances to be suspended. This left the singers with only their meagre basic salaries, so the three decided to remedy the situation by accepting engagements elsewhere, even though they were prohibited by law from doing so as salaried artistes of the Académie Royale de Musique. Rousseau alone managed to travel to Brussels surreptitiously and appear at the Théâtre de la Monnaie, then the second most important French-speaking theatre in the world. Lays, however, was arrested on the evening of 20 August 1781, the day before he was due to set off, and spent ten days in prison.[13] He was provisionally released on the 30th because he was indispensable for filling the haute-contre role of Cynire in a revival of Gluck's Echo et Narcisse[14] in the small hall of the Menus-Plaisirs which acted as a substitute for the theatre which had burned down. His enormous popularity with the public, with an encore of the main aria and several curtain-calls, made it practically impossible to send him back to prison, although he was forced to sign a solemn undertaking that he would not leave Paris without the express permission of his superiors.[15]

In 1782, the director of the Opéra, Antoine Dauvergne, was forced to resign his post and the management of the theatre was assumed by the artists acting as a kind of cooperative. The results were so disastrous that the former director had to be recalled in April 1785, although even then his relationship with the trio of rebel singers did not improve very much. In a report to his superiors,[16] Dauvergne described Lays as the black sheep of the group, Rousseau as a "nice young man", if only he had spent less time in the company of Lays, and Chéron as another "nice young man" (with the mind of a twelve-year-old), but scared of the beating Lays and Rousseau had promised him if he betrayed their alliance. In the end, the three had to bow to pressure from the theatre management, although not before being promoted to "Premiers Sujets" (leading artistes), the highest rank in the company hierarchy.[17]

Revolutionary era

A long-time Freemason[18] and an avid reader of Rousseau, after the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789 Lays joined the Jacobin Club under the patronage of his old friend Barère.[19] Lays was a passionate believer in the ideals of the Revolution, promoting them among the members of the Opéra company, which had been renamed Théatre des Arts. This was not enough, however, to prevent his arrest in 1792 as a suspected royalist, on the grounds that he had been a leading singer in the Queen's concerts and the Grand Couvert. Only the timely intervention of Barère secured his release after a single night in prison.[20]

It was on Barère's prompting that Lays decided to return to his native Gascony in 1793 as a propagandist for the new Reign of Terror. He was accompanied by his future wife, a young unemployed diamond-polisher named Marie Barbé.[11] In Girondin Bordeaux, his political alignment with the Montagnards provoked such public hostility that he was forced to slip out of the city without even being able to complete his debut performance at the local theatre. Things went much better in his native region, the newly established département of Hautes-Pyrénées, where the Barère clan were politically dominant and where Lays received a hero's welcome. He returned to Paris in mid-July via Toulouse, thus avoiding the hostile Bordeaux.[21] Back in the capital, he delivered a much applauded speech in front of the Commune of Paris.[22]

Lays's direct involvement in political life went little further than this, but, contrary to the claims of the brothers Michaud and Fétis, it was enough to cause him unpleasant repercussions when in 1794 the coup of 9 Thermidor and the downfall of Robespierre radically changed the political situation. Lays was branded a "Terrorist actor" alongside other leading performers with a Revolutionary past, such as Talma, Dugazon and Antoine Trial; and he was forced to try to defend himself by publishing a pamphlet entitled Lays, artiste du théatre des Arts, à ses concitoyens.[23] When a warrant was issued for the arrest of Barère and three of his colleagues from the Committee of Public Safety in March 1795, other associates were implicated in his downfall: Lays was arrested and imprisoned for about four months together with an old friend who had shared his political trajectory – although his role had been far more prominent – the painter Jacques-Louis David.

After his release on 3 July, Lays had to undergo the ritual humiliation the public was imposing on the "Terrorist actors": they were forced to sing the anti-Jacobin hymn "Le Réveil du Peuple", which had just been set to music by a tenor from the Théâtre Feydeau, Pierre Gaveaux, and which seemed destined to replace the Marseillaise as the main Republican anthem. Antoine Trial, a colleague of Gaveaux from the Opéra-Comique who was then in his sixties, had been forced to sing the new hymn kneeling on stage to boos, whistles and jeers from the audience, and had never recovered from the experience, eventually taking his own life with poison.[24] Quéruel writes Lays managed to avoid making his return to the stage in Iphigénie en Tauride, in which his character Oreste sang lines which were a little too suggestive coming from an ex-"Terrorist": "J'ai trahi l'amitié, j'ai trahi la nature/Des plus noirs attentats, j'ai comblé la mesure" ("I have betrayed friendship, betrayed Nature/I have gone to the extreme of blackest deeds"). On the other hand, according to the memoirs of Count Jean-Nicolas Dufort de Cheverny, it was indeed in the role of Oreste that Lays sought to return to the stage. However, the implacable hostility of the audience prevented him from singing a single note and, after an hour of fruitless efforts, he eventually had to be replaced by an understudy.[25] His actual reappearance then took place in a revival of Sacchini's Œdipe à Colone, in which he sang the far less controversial character of King Theseus. Even then, things did not go smoothly: the audience booed and protested throughout the performance, although this time he was not prevented from completing it. At the end, the leading tenor Étienne Lainez returned onto the proscenium to sing, as usual, Le Réveil du Peuple, but he was shouted down and forced to take refuge in the wings. Lays was rowdily summoned back instead. Lainez accompanied his colleague on stage, hoping they would be allowed to sing together, but he was once more driven off by the furious audience, and Lays had to perform solo. No sooner had he managed to get through a couple of verses, however, than he too was driven off by booing, because the audience thought he was unworthy of the words he was singing. The unfortunate Lainez had to retake the stage for a third time to finish the performance. By the end of September, nevertheless, enthusiasm for such post-Revolutionary reprisals had abated and Lays was able to make a triumphant return as the Genius of Fire in Salieri's Tarare, his debut in the role.[26]

The Directory and Napoleonic era

Over the course of 15 years Lays had built a remarkable reputation as a singer. He had been a star at the court of the Ancien Régime, before performing at the opening of the Estates General at Versailles in 1789. Later he had sung several works by Gossec at some of the grandest ceremonies of the French Revolution: he had performed in the Te Deum at the Fête de la Fédération on 14 July 1790; he had sung the funeral hymns when Mirabeau's and Voltaire's mortal remains were transferred to the newly established Panthéon in 1791;[27] and he had sung the Hymne à l'Être-suprême at the Festival of the Supreme Being in June 1794.[11] So it was unsurprising that his career continued to thrive in the new political climate under the government of the Directory. Lays was protected by the strong man of the new regime, Paul Barras, and became friends with his mistress, Josephine de Beauharnais, as well as the man who would become her husband, General Napoleon Bonaparte.[28] With such patrons his position over the next two decades was secure.

In late 1795, Lays was named Professor of Singing at the newly opened Paris Conservatoire. Four years later he resigned to avoid being involved in the quarrel then raging between the managements of the Conservatoire and the Opéra.[3] Quéruel credits Lays with teaching two future stars of the Opéra: Madame Chéron and Mademoiselle Armand.[29] The latter is a possibility;[30] the former[31] had begun her career in 1784 under the name Mademoiselle Dozon, and is thus unlikely to have attended the Conservatoire more than a decade later. Lays did play a part in promoting her early career: he had auditioned her when she was a young unknown in 1782 and had facilitated her studies, entrusting her to the best singing teachers available.[32]

In January 1797, Lays enjoyed one of the biggest successes of his career when he sang the lead role in Grétry's Anacréon chez Polycrate. The takings from this opera (9,354 livres on the first night alone) helped rescue the disastrous finances of the Théâtre de la République et des Arts (as the Opéra had been renamed).[33] If the quality of his voice was universally admired, his lack of physical elegance, his short and stocky build and the southern accent he never completely managed to lose predisposed Lays to comic rather than dramatic roles, particularly middle-aged buffo characters, in which, "singing of love and good wine, he proved to be sublime".[34] Anacreon was one such role. Lays played the character again in 1803 in the opera Cherubini dedicated to the ancient Greek poet. A few decades later, Castil-Blaze – referring to the work by Grétry – commented:

The opera sparkles with charming melodies; the role of Anacreon is the most beautiful, the most complete ever written for Lays, the marvellous sonority of whose voice was deployed so well in the ascending virtuoso passage "Prends, prends emporte mon or, mes trésors pour jamais." The trio "Livre ton cœur à l'espérance" makes a delightful impression." (Castil-Blaze, L' Académie impériale de musique (...) – De 1645 à 1855, Paris, Castil-Blaze, 1855, II, p. 61)[35]

The year 1798 was a turning point in Lays's private life: Marie Barbé, with whom he had been living for several years, gave birth to a daughter and Lays, to legitimise the child, decided to marry his companion, even though it was against his father's wishes. Old Lay was furious that his eldest child, who enjoyed a successful career, was marrying a foreign woman with no property. The couple went on to have four more children, including one son who would unwittingly cause Lays enormous grief.[36]

In the same year, Lays politely refused Napoleon's invitation to join him on his expedition to Egypt. Nevertheless, the pair remained on friendly terms and between 1801 and 1802, Lays – who had often performed in Josephine's salons – became chief singer of the Chapel Napoleon had established at the Tuileries under the directorship of Giovanni Paisiello.[37] As such, three years later, on 2 December 1804, Lays was the lead soloist in the music accompanying Napoleon's coronation as emperor. The ensuing celebrations culminated at the Hôtel de Ville on 16 December with Lays and Chéron singing the cantata Trasibule, specially written for the occasion by Henri-Montan Berton.[38] In 1810, when Napoleon divorced Josephine and entered into a second marriage with the Austrian Archduchess Marie Louise, Lays was the obvious choice to perform at the wedding ceremony. Meanwhile, his stage activity continued unabated, and in 1807 he was also appointed to serve on the Opéra jury in charge of evaluating new works to be staged.[39] Other members of the jury came and went, but Lays remained in office continuously until 1815.[40]

Final years

At the fall of Napoleon in 1814, Lays was one of the Emperor's most prominent favourites, so when the allied armies entered Paris under the leadership of Tsar Alexander I, he was understandably worried about his own future. On 2 April, Talleyrand ordered the Opéra to mount a performance in honour of the tsar. The opera chosen, Le triomphe de Trajan by Persuis and Lesueur, had originally been given in 1807 to celebrate Napoleon's return to the capital. Not wanting to hurt the French public's feelings, Alexander requested a staging of Spontini's La vestale instead, an opera in which Lays always assumed the role of Cinna. At the end of the performance, the angry audience forced Lays – still dressed in his Roman toga – to return to the stage and recite some popular verses thanking the tsar for restoring the Bourbons.[41] According to the brothers Michaud, Alexander was moved to compassion by the sight of the terrified singer and sent one of his aides-de-camp on stage to reassure him.

The first Restoration was quite mild and the only significant penalty Lays suffered was his dismissal from the former Chapelle Impériale with a resulting loss of income. When Napoleon returned to power for the so-called Hundred Days, Lays was inevitably reinstated in his post and he enthusiastically participated in the Te Deum of thanks. The second Restoration of the Bourbons was more serious for Lays.[42] At the express wish of Louis XVIII he was again expelled – this time for good – from the new Chapelle Royale, but in return, in 1816, he was named professor of declamatory singing at the École royale de Musique et de Déclamation, which had replaced the Conservatoire. The salary was indispensable to Lays because his gout meant he was no longer able to appear at the Opéra as regularly as he had done, leading to a drastic reduction in extra income.[43]

In 1816, Lays had the satisfaction of enjoying one final triumph in the comic opera Le rossignol by Louis-Sébastien Lebrun (1764–1829), set in the foothills of his native Pyrenees. Lays took one of his favourite stock parts, "a bailiff in his fifties, a lover of good food and beautiful young women, naive and credulous, convinced of his own powers of seduction. The audience, at first amused and then enthralled, gave him a standing ovation which cheered his heart." However, things subsequently took a turn for the worse. In 1817, the restored Intendant of the Menus-Plaisirs du Roi, Papillon de la Ferté[44] abolished all additional emoluments granted by Napoleon, leaving the singer to survive on his meagre salary from the school of music and the minimum pay from the Opéra, at the very time when his son, stricken with tuberculosis, required expensive medical treatment and his four daughters needed money for their dowries. Lays turned to Luigi Cherubini.[45] Lays had repeatedly supported Cherubini when Napoleon had shown signs of dislike for the composer. Cherubini had now become one of the leading figures in the musical establishment under the Restoration.[46] He immediately intervened on Lays's behalf, but all he could obtain from Ferté was the advice that the singer should go on a tour of the provinces as a way of supplementing his income.Having obtained leave of absence, Lays appeared in Nancy (where performances were interrupted by the death of the leading soprano) and Strasbourg, where Lays himself was obliged to interrupt them with disastrous effects on his finances: he had been unexpectedly summoned back to Paris on the pretext he was urgently needed for rehearsals of a new opera, Les jeux floraux; in reality, the rehearsals only took place two months later. Lays then applied to the royal administration, insisting he should be granted some of the potential economic benefits provided by law, but, after the new opera's premiere, his demands received a blanket rejection. According to Quéruel, when he protested stridently about this decision, he was forced into unpaid leave from his theatrical activities in late 1818. He subsequently spent about two years of hardship, during which his need to provide a dowry for his eldest daughter Marie-Cécile forced him further into debt.[47]

Quéruel relates that Lays was finally reinstated only on 9 January 1821, but this assertion cannot be accurate because the singer's name often appeared on the theatre bills in the meantime, for example the whole period between July 1819 and June 1820.[48] Whatever the case, in response to his renewed demands for economic support, the administration granted him further leave to perform privately outside Paris. Lays went on a tour of the Low Countries and also put on several performances of Anacréon chez Polycrate[49] at the same Brussels Théâtre de la Monnaie to which he had tried to escape forty years earlier.[50] The reviews from the local newspaper, the "Mercure belge", reported by Quéruel tell of a real triumph. On his return to Paris, however, he was greeted with disastrous news. It was now obvious that the singer had been targeted in high places: the Minister of the Maison du Roi, General Jacques Alexandre Law de Lauriston, who was ultimately in charge of the theatre, had discovered he had not previously authorised the leave of absence granted to Lays and, regarding it as null and void, intended to sue him for damages for missing performances at the Opéra.[51] The confrontation lasted for more than a year until, in 1823, the moment came for Lays to leave the Opéra after almost 45 years of outstanding service. The benefit concert, to which artistes were entitled on their retirement, took place on 1 May. The performance ended with Le rossignol, during which almost all the stars who did not have roles in the opera paid homage to their respected and well-liked colleague by appearing on stage in the chorus. The first part of the concert saw the company of the Théâtre-Français transfer to the Opéra for a revival of Racine's tragedy Athalie, performed with incidental music and choruses by Gossec.[52] The leading roles were taken by three star actors: Lays's old friend and political ally, Talma; the great Racine specialist Mademoiselle Duchesnois; and Pierre Lafon. The "premiers sujets" of the Opéra sang as simple "coryphées" in the chorus. The takings were considerable, amounting to the remarkable sum of 14,000 francs.[53] According to Quéruel, however, shortly afterwards a peremptory letter from the administration dated 1 June 1823 informed Lays of its intention to use the takings from the performance to make good the debts it claimed Lays owed it. It is not entirely clear, from Quéruel's account, how the issue was finally resolved. Whatever the case, the financial position of the singer and his family remained extremely precarious. He still kept his teaching post at the École royale de musique et de déclamation, but the salary and pension were clearly not enough for him to cope with his debts and live a comfortable life, and thus, in spite of his ailing health and his now worn-out voice, he was forced to accept engagements, however humiliating, from provincial companies, just to make ends meet. According to Quéruel, posters of the time show he worked as an understudy in a company in Brest, a baritone in the choir of the Dunkirk Opera, a reserve baritone in Lille, a bass soloist in Valenciennes, and once more as a simple understudy at the Metz opera house.

In late 1825, however, Lays again took to the Opéra stage in a benefit concert for the great singer Giuditta Pasta. The show, held on 8 October, was a double bill: the final Paris performance of Meyerbeer's Il crociato in Egitto followed by another revival of Le rossignol. Meyerbeer's opera had previously been staged at the Théâtre italien and was performed by an almost entirely Italian company led by Pasta and Domenico Donzelli. In Le rossignol, Lays once more played his favourite character of the bailiff, while the principal female role of Philis was taken by Laure Cinti-Damoreau,[54] a pupil of Rossini, soon to become the leading lady in the composer's French operas.[55]

New political developments did not bode well for Lays. Charles X, who had come to the throne in 1824, named the ultra-royalist Sosthène de La Rochefoucauld as Director General of the Fine Arts. La Rochefoucauld had an aversion to Lays both as an inveterate supporter of the Revolution, and, in particular, for the ironic remarks the singer had made about his morality campaign, which included lengthening ballerinas' skirts and providing ancient statues with fig leaves. In 1826, La Rochefoucauld had the opportunity to demonstrate his dislike when Lays, realising that life in Paris was beyond his financial means, decided to leave his post as professor and retire to the provinces to be near his married eldest daughter. According to Quéruel. Lays, probably wanting to end his career of more than 40 years on a high note, sent the minister a petition signed by almost all the stars of the Opéra and backed by Cherubini, asking for another benefit concert, in addition to the one three years earlier, this time in aid of his son who was working as a saute-ruisseau'[56] at a notary's and whose legal studies Lays could not afford to maintain. Inevitably the request fell on deaf ears. Lays also asked for his pension to be recalculated, bearing in mind his years teaching at the conservatory. But this led to disputes to which the correspondence between Cherubini and La Rochefoucauld bears explicit testimony. In October, the former wrote:[57]

I have the honour to inform you that Monsieur Lays has retired and is asking for his pension. There is no doubt that he has a right to such recompense. There is no need to tell you of the talent of this famous artist, whose career has been long and fruitful. His reputation, which has endured for half a century, makes all such talk superfluous. In the interests of the professor, I must add that it is the meagreness of his fortune more than his age which has forced him to ask for his pension. No longer able to live in the capital in the manner to which he is accustomed, his intention is to retire to somewhere in the provinces where he and his family will be able to live more comfortably.

A week later, having received no reply, Cherubini tried again:

Permit me to bring to your attention the services he has rendered to musical and dramatic art, and the regrettable situation in which he finds himself after such long services as well as having to provide for a large family.

No response having come from the administration, Quéruel claims that Cherubini made the courageous decision to use his discretionary powers and take personal responsibility for authorising a special performance whose takings would be divided equally between the Académie and Lays. Even if it is unclear what right the director of the École royale de musique et de déclamation had to make such a decision, the performance did in fact take place at the Opéra on 20 November 1826. The programme consisted of Boieldieu's opéra comique Le calife de Bagdad; the second act of Anacréon chez Polycrate, in which Lays played his most famous role for the last time; and the four-act pantomime-ballet Mars et Vénus, ou Les filets de Vulcain with music by Jean Schneitzhöffer. However, the evening's takings of between 6,000 and 7,000 francs were markedly inferior to those Lays's presence on stage would once have guaranteed.[58]

La Rochefoucauld's reply on the issue of the pension was delayed until January 1827, when he stated that Lays was not entitled to any pension increase with regard to his previous years of teaching, having already received the maximum provided for as a result of his theatrical activity, and having furthermore shared half the takings from an extra benefit performance. Meanwhile, Lays, his wife and unmarried daughters, had retired to Ingrandes in the Loire valley, where they joined his married daughter Marie-Cécile. Here he had already witnessed the death of his son Bertrand from consumption and was soon to see his wife stricken with paralysis. In his final years Lays spent his time singing hymns in local churches.[59] He died aged 73 in 1831, leaving his wife and children the paltry sum of 1056 francs.[60]

Artistic characteristics

As mentioned above, Lays's voice was classified as basse-taille in the Opéra company, a voice type which was initially roughly equivalent to the modern bass-baritone, but by the latter half of the 18th century had come to designate all low male voices. According to the brothers Michaud, however, Lays "was not strictly a basse-taille, although he sometimes forced his voice downwards excessively to reach the lower notes, and he was listed among the company's leading basse-tailles", neither was he, contrary to some erroneous contemporary descriptions, a tenor: he was in fact "an admirable baritone or concordant, low, pure, sonorous and flexible, whose range and volume were amazing".[22] Irish tenor Michael Kelly, who happened to hear him in the 1780s, wrote that "Monsieur Laisse" possessed "a fine baritone voice, with much taste and expression".[61] The majority of modern authors share these opinions. According to Elizabeth Forbes, for instance, he possessed a "voice, baritonal in quality, but which extended into the tenor range".[62] In fact, his roles were mostly notated in the bass clef,[63] but there are also cases where the tenor clef was preferred, such as the title role of Anacréon (1803) by Cherubini,[64] or the role of Cinna in La Vestale (1807) by Spontini.[65]

While there seems to have been no doubt about the great beauty of Lays's voice, which he was able to preserve throughout his career, Fétis criticised his skill in managing it:

In spite of the long-lasting enthusiasm he aroused among the habitués of the Opéra, Lays was not a great singer: one might even say he knew nothing about the fundamentals of the art of singing. His vocalisation was clumsy; he had not learned how to equalise the registers of his voice, and when he changed from chest voice to mixed voice it was by a sudden leap from a mighty organ tone to a sort of flute-like voice, which had a ridiculous rather than pleasant effect. Nonetheless, he used to show off this effect, which would make the aficionados of the time swoon with pleasure. Most of his ornamentation was old-fashioned and tasteless; in spite of these faults, the beauty of his voice made almost everyone who heard him into an admirer, and it was scarcely possible for an opera to succeed unless Lays had a role in it.

— François-Joseph Fétis, Biographie universelle des musiciens et Bibliographie générale de la musique (second edition), Paris, Didot, 1867, V, p. 236

Spire Pitou draws readers' attention to this last point in his work on the Paris Opéra. Pitou was evidently unaware of Lays's attempted flight to Brussels in 1781 and the troubles of his final years, but his comments appear worthy of note nevertheless:

The most impressive aspect of Lays's professional life was not in the quality of his voice, but in the number of times that he used it. He created 68 new characters at the Opéra between 1780 and 1818. It would be interesting to determine how many records he broke in the course of performing this single feat alone. How many singers have had a longer tenure at the Opéra? Has any artist created more roles at the Opéra? What singers besides Lays have learned five new parts in a year? He performed before the days of planes and fast trains, of course, but even making allowances for this lack of temptation to interrupt his activities in Paris to visit foreign opera houses for large fees, modern critics must credit Lays with a singleness of purpose that merits recognition.

— Spire Pitou, The Paris Opéra. An Encyclopedia of Operas, Ballets, Composers, and Performers – Rococo and Romantic, 1715–1815, Westport/London, Greenwood Press, 1985, p. 329

The number of 68 characters listed by Pitou is incomplete. In fact, the roles Lays created amount to at least 73 (cf next section). Moreover, this obviously does not include the roles Lays did not create directly (including those already mentioned, such as Thésée in Sacchini's Œdipe à Colone, Oreste in Iphigénie en Tauride and Cynire in Echo et Narcisse, both by Gluck, as well as Patrocle in the same composer's Iphigénie en Aulide and Figaro in Le Mariage de Figaro by Mozart).[66] Lays's contribution to the Opéra repertoire, which lasted over forty years, was astonishing, and the long duration of the singer's career and the good vocal form he maintained to the last suggest that Fétis's adverse judgement on his technical skills should be accepted only with caution.

Roles created

The following table contains a list of the roles created by François Lays in the course of his long career. The information is mostly taken from Spire Pitou in his book on the Paris Opéra cited in the bibliography.

| Character | Opera | Composer | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pétrarque[67] | Laure et Pétrarque | Pierre-Joseph Candeille | 1780 |

| Thésée[68] | Ariane dans l'isle de Naxos | Jean-Frédéric Edelmann | 1783 |

| Panurge | Panurge dans l'île des lanternes | André Grétry | 1785 |

| Jason[69] | La toison d'or | Johann Christoph Vogel | 1786 |

| Alcindor | Alcindor | Nicolas Dezède | 1787 |

| Pollux[70] | Castor et Pollux | Pierre-Joseph Candeille | 1791 |

| Anacréon | Anacréon chez Polycrate | André Grétry | 1797 |

| Praxitèle | Praxitèle | Jeanne-Hippolyte Devismes | 1800 |

| Mars[71] | Le casque et les colombes | André Gretry | 1801 |

| Delphis | Delphis et Mopsa | André Grétry | 1803 |

| Pluton[72] | Proserpine | Giovanni Paisiello | 1803 |

| Anacréon | Anacréon | Luigi Cherubini | 1803 |

| Aristippe | Aristippe | Rodolphe Kreutzer | 1808 |

| Sophocle | Sophocle | Vincenzo Fiocchi (1767–1845) | 1811 |

| Pélage | Pélage | Gaspare Spontini | 1814 |

| Roger | Roger de Sicile | Henri-Montan Berton | 1817 |

| A follower of Morpheus[73] | Atys | Niccolò Piccinni | 1780 |

| Proténor[74] | Persée | François-André Danican Philidor | 1780 |

| Le Bailli | Le seigneur bienfaisant | Étienne-Joseph Floquet | 1780 |

| A Scythian | Iphigénie en Tauride | Niccolò Piccinni | 1781 |

| Florival | L'inconnue persécutée | Pasquale Anfossi e Jean-Baptiste Rochefort (1746–1819) | 1781 |

| Bastien/A gipsy | Colinette à la cour | André Grétry | 1782 |

| Égiste | Électre | Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne | 1782 |

| Myrtile | L'embarras des richesses | André Grétry | 1782 |

| Hidraot | Renaud | Antonio Sacchini | 1783 |

| Gandartès | Alexandre aux Indes | Nicolas-Jean Lefroid de Méreaux | 1783 |

| Husca | La caravane du Caire | André Grétry | 1784 |

| The king | Chimène | Antonio Sacchini | 1784 |

| Anténor | Dardanus | Antonio Sacchini | 1784 |

| Germond | Rosine | François-Joseph Gossec | 1786 |

| Young Horace[75] | Les Horaces | Antonio Salieri | 1786 |

| Thaddée | Le Roi Théodore à Venise | Giovanni Paisiello | 1787 |

| Vellinus | Arvire et Évélina | Antonio Sacchini and Jean-Baptiste Rey | 1788 |

| Astor | Démophoon | Luigi Cherubini | 1788 |

| Aristophane | Aspasie | André Grétry | 1789 |

| Baron de la Dardinière | Les prétendus | Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne | 1789 |

| Narbal | Démophon | Johann Christoph Vogel | 1789 |

| Mathurin | Les pommiers et le moulin | Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne | 1790 |

| Mozès | Louis IX en Égypte | Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne | 1790 |

| Le Sauvage | Le portrait | Stanislas Champein | 1790 |

| Atabila | Cora | Étienne Nicolas Méhul | 1791 |

| Lourdis | Corisandre | Honoré Langlé | 1791 |

| Thomas | Le triomphe de la république | François-Joseph Gossec | 1793 |

| Démosthènes | Toute la Grèce, ou ce qui peut la liberté | Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne | 1794 |

| Valerius Publicola | Horatius Coclès | Étienne Nicolas Méhul | 1794 |

| A criminal | Toulon soumis | Jean-Baptiste Rochefort | 1794 |

| L'ordonnateur chantant | La réunion du 10 août | Bernardo Porta | 1794 |

| Le curé | La rosière républicaine | André Gretry | 1794 |

| Un commissaire de la majorité des sections | La journée du 10 août 1792 | Rodolphe Kreutzer | 1795 |

| Flaminius | Adrien | Étienne Nicolas Méhul | 1799 |

| Young Horace | Les Horaces[76] | Bernardo Porta | 1800 |

| Chariclès | Flaminius à Corinthe | Rodolphe Kreutzer and Nicolas Isouard | 1801 |

| Bochoris | Les mystères d'Isis | pastiche[77] | 1801 |

| Moctar | Tamerlan | Peter von Winter | 1802 |

| David | Saül | pastiche[78] | 1803 |

| Morat | Mahomet II | Louis Emmanuel Jadin | 1803 |

| Rustan | Le pavillon du calife | Nicolas Dalayrac | 1804 |

| Hidala | Ossian, ou Les bardes | Jean-François Lesueur | 1804 |

| Éliézar | Nephtali, ou les Ammonites | Felice Blangini | 1806 |

| Licinius | Le triomphe de Trajan | Louis-Luc Loiseau de Persuis and Jean-François Lesueur | 1807 |

| Cinna | La vestale | Gaspare Spontini | 1807 |

| Seth | La mort d'Adam | Jean-François Lesueur | 1809 |

| Telasco | Fernand Cortez | Gaspare Spontini | 1809 |

| Roger | Jérusalem délivrée | Louis-Luc Loiseau de Persuis | 1812 |

| Kan-si | Le laboureur chinois | pastiche[79] | 1813 |

| Le chef des vieillards | L'Oriflamme | Étienne Nicolas Méhul, Ferdinando Paër, Henri-Montan Berton and Rodolphe Kreutzer |

1814 |

| Socrate | Alcibiade solitaire | Louis Alexandre Piccinni | 1814 |

| Le bailli | Le rossignol | Louis-Sébastien Lebrun (1764–1829) | 1816 |

| Bacchus[80] | Les dieux rivaux, ou Les fêtes de Cythère | Gaspare Spontini, Rodolphe Kreutzer, Louis-Luc Loiseau de Persuis and Henri-Montan Berton |

1816 |

| Voldik | Nathalie, ou La famille russe | Antonin Reicha | 1816 |

| Colibrados | Zéloïde | Louis-Sébastien Lebrun | 1818 |

| Béranger[81] | Les jeux floraux | Pamphile Léopold François Aimon | 1818 |

| Le cadi[82] | Aladin, ou la Lampe merveilleuse | Nicolas Isouard, Angelo Maria Benincori and François-Antoine Habeneck |

1822 |

References

- His surname is also written as Laï, Laïs or Laÿs, French orthography of the period being rather unstable. According to Quéruel (p. 21), the stage name originally chosen by the singer, "M. Laÿs" (no doubt pronounced 'la-ìs' [laˈis] and whose diaeresis would eventually be dropped), was intended to avoid puns on his original surname, pronounced 'la-ì' [laˈi] in Occitan but running the risk of being interpreted differently by French-speakers, probably as 'lè' [lɛ], the same as the word "laid" (ugly).

- The date 27 March is attested in the biography by Anne Quéruel. On the other hand, Fétis, Pitou and Elizabeth Forbes give the date of his death as 30 March.

- Fétis, op.cit.

- Quéruel, p. 18 ff.

- Quéruel, p. 7. La Provençale was an entrée added in 1722 by Jean-Joseph Mouret to his opéra-ballet Les Festes de Thalie. It remained popular throughout the 18th century. In 1778 most of the entrée was set to new music by Candeille to be given as part of a performance of "fragments" (also called "spectacles coupés") which were very common in the latter half of the 18th century, or as an intermezzo to the opere buffe by Italian composers the Académie Royale de Musique was staging at the time.

- Jullien, pp. 90–91.

- Castil-Blaze, L'Académie Royale de Musique (3e époque – 6e article), "Revue de Paris", New series, Year 1837, 37th volume, p. 23 (accessible for free online at Google Books).

- George Grove, Lays [Lai, Laïs, Lay], François, in Stanley Sadie (ed.), John Tyrrell (ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2ª ed., Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0195170672.

- Fétis, op.cit.; Pitou, p. 493 (article: Le Seigneur bienfaisant). Fétis writes that the role was specifically composed with Lays in mind, whereas the 1781 libretto ascribes the character to another basse-taille of the company, M. Durand (Le Seigneur bienfaisant, Opéra, composé des actes du Pressoir ou des Fètes de l'Automne, de l'Incendie, et du Bal, Paris, aux dépens de l'Académie, 1881, p. 8, accessible online at Google Books). The review published by the "Mercure de France" reports that Lays did in fact appear at the premiere and the audience did not appreciate the long arietta he sung: his performance, however, was much praised by the reviewer ("Mercure de France", 30 December 1780, pp. 222–223, accessible online at Google Books).

- Literally meaning 'a gala dinner', the term refers to the Versailles custom of performing music on the occasions when the royal couple had dinner in public in the antechamber of the Grand Couvert. The custom had been introduced by Marie Antoinette who wished to relieve the boredom of the public dinner ceremonial (cf. Chateau de Versailles website).

- Quéruel, Tableau chronologique, pp. 165–171.

- Sources traditionally report only the initial letter (J.) of this singer's name; full details, however, can be found in "Organico dei fratelli a talento della Loggia parigina di Saint-Jean d'Écosse du Contrat Social (1773-89)" (list of the members of this Masonic lodge), reported as an Appendix in Zeffiro Ciuffoletti and Sergio Moravia (eds), La Massoneria. La storia, gli uomini, le idee, Milan, Mondadori, 2004, ISBN 978-8804536468 (in Italian).

- Prison (or the threat of prison) was a fairly common method of bringing the Opéra's intractable artistes to heel. In 1771, for instance, the principal tenor Joseph Legros, believing the role he had been allotted in La Borde's pastorale La Cinquantaine was supremely silly and tasteless, initially refused outright to perform it. However, according to an indignant Mathieu-François Pidansat de Mairobert, he eventually had to bow to La Borde's threat of making him spend a good fifty days in For-l'Évêque prison (Louis Petit de Bachaumont et al., Mémoires secrets..., London, Adamson, 1784, 5th tome, p. 296, accessible online at Google Books). Things went even worse for his successor Étienne Lainez. So deep was his loathing for the title role of Salieri's Tarare (1787), that the Opéra's musical director, Louis-Joseph Francœur, was only able to persuade him to appear in the sixth performance of the opera by informing him he had a warrant for the singer's arrest in his pocket. This was not enough, however, to prevent Lainez from being imprisoned on 25 November after he had again repeatedly refused to assume the hated role of Tarare (Lajarte, p. 358).

- According to Quéruel, in 1781 Lays was going to take the role that had been created two years before by Henri Larrivée, the company's leading bass-baritone. In fact, Larrivée had not appeared in the premiere of Echo et Narcisse, where there are no bass-baritone leads, and the role of Cynire had been performed by the principal haute-contre Joseph Legros. The versatile Lays was probably just covering for his comrade Rousseau during the emergency created by latter's escape abroad. A hand-written score kept at the Bibliothèque nationale de France shows some changes made to the part of Cynire which are expressly designated "pour Lays" (for Lays): like the rest of the part, they are notated in the alto clef (C-clef on the third line) which was customarily used for the haute-contre voice.

- Quèruel, Chapter 2, Le rebelle – 1779–1788, pp. 25–49 (passim)

- "Compte rendu des propos indécents tenus dans la séance de l'Academie Royale de Musique du 1er mars 1786" (Quéruel, p. 37).

- (in French) Youri Carbonnier, Le personnel musical de l'Opéra de Paris sous le règne de Louis XVI, "Histoire, économie et société", 2003, 22-2, 177-206, p. 192 (accessible online at Persée).

- The presence of Lays, Rousseau and Chéron at a funeral ceremony held in 1785 by the Paris lodge of Les Neuf Sœurs, where they performed a Masonic hymn by Piccinni, is attested by Guillaume Imbert de Boudeaux in Correspondance secrète, politique, & littéraire (London, Adamson, 1789, XVII, p. 402; accessible for free online at Google Books). According to the website Musée virtuel de la musique maçonnique (accessed on 6 May 2015), Lays and Rousseau were members of both Les Neuf Sœurs and the lodge of Saint Jean d'Écosse du Contrat social, whereas Chéron was only a member of the former (sources cited: Louis Amiable, Une loge maçonnique d'avant 1789, la loge des Neuf Sœurs, Paris, Alcan, 1897, pp. 339 and 350, accessible for free online at Internet Archive; Alain Le Bihan, Francs-maçons parisiens du Grand Orient de France (fin du XVIIIe siècle), Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, 1966).

- Quéruel, pp. 57 and 166.

- Quéruel, pp. 66–69.

- Quéruel, pp. 83–89.

- Michaud, op.cit.

- (in French) François Gendron, La jeunesse sous Thermidor, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1983, p. 90. According to Fétis, the pamphlet (said to have become "excessively rare", and thus probably not consulted at first hand) had instead been published in 1793 (an octavo of 23 pages), and it is therefore described as a sort of report Lays made on his previous revolutionary activities after his expedition to Gascony. The thesis upheld by Gendron, however, is confirmed by the book Essai d'une bibliographie générale du théatre, compiled by Joseph De Filippi (Paris, Tresse/Aubry, 1864, p. 170, accessible online at Google Books), where it is stated that the pamphlet was published as an octavo in Paris in the month of Vendemiaire Year III (i.e. in September/October 1794, after the coup of 9 Thermidor Year II), and that through it "the author tries to justify his political behaviour". Surprisingly, Quéruel makes no reference to the pamphlet.

- Trial also found it unbearable that he had been dismissed from the political office he had held under the Paris Commune. He remains famous in musical history for giving rise to a new type of French comic tenor, named "Trial" after him.

- Jean-Nicolas Dufort de Cheverny, Mémoires sur les règnes de Louis XV et Louis XVI et sur la Révolution (publiés avec une introduction et des notes par Robert de Crèvecœur), Paris, Plon, 1882, II, p. 257 (accessible online at Internet Archive).

- Quéruel, p. 101 ff.

- According to Quéruel, the hymn performed on the occasion of the transfer of Voltaire's mortal remains, where " Laÿs's superb voice" rose over Chéron's and Rousseau's responding in chorus, had been set to music by Étienne Méhul. However, other sources do not support this information. On the contrary, they are unanimous in attributing to Gossec a Hymne sur la translation du corps de Voltaire au Panthéon, for voice and brass or for three voices, male choir and band (cf. catalogue of Gossec's works at musicologie.org 2014).

- Quéruel, p. 107 ff.

- Quéruel, p. 109

- Provided this is Joséphine Armand (1787–1859), although still a young girl at the time, and not her better known aunt, Anne-Aimée (1774–1846), who was professionally active at the Opéra-Comique from 1793 to 1801 (Pitou, pp. 50–51) and thus unlikely to have attended the Conservatoire in the same period.

- She was born Anne Cameroy (1767 – c. 1862), and married Lays's friend, Auguste-Athanase Chéron.

- (in French) Youri Carbonnier, Le personnel musical de l'Opéra de Paris sous le règne de Louis XVI, "Histoire, économie et société", 22 February 2003, p. 179 (accessible online at Persée). Quéruel's mistake is probably due to the contents of a letter Lays sent to Cherubini in July 1826 (which is quoted by Quéruel herself on page 156). Aiming to have his pension favourably recalculated, Lays claimed he had discovered two future leading Opéra sopranos, but, obviously, no more than one (if any) could possibly be credited to his teaching at the Conservatoire.

- Quéruel, pp. 109 ff.

- Quéruel, p. 112

- Accessible online at Internet Archive.

- Quéruel, p. 116 ff.

- Queruel, pp. 114 ff. The date of the appointment is not very clear in Quéruel's text: in the final Tableau Chronologique the year 1799 is stated, but this date is evidently inaccurate given that Napoleon became First Consul only at the end of November. In the main part of her book, however, Quéruel also reports a conversation between the singer and the First Consul, during which the latter, proposing Lays's appointment, refers to Paisiello's direction of the Chapel, which only began in January 1802.

- Quéruel, pp. 125–29

- He had already been a member of the literary jury under the Ancien Régime and the Republic.

- Quéruel, pp. 133 ff.

- Quéruel, p. 140 ff. The lines were taken, with appropriate changes, from the popular comedy by Collé, La partie de chasse de Henri IV. They ran as follows: "Vive Alexandre/vive ce Roi des Rois!/Sans rien prétendre/Sans nous dicter ses lois,/Ce prince auguste/A ce triple renom/De héros, de juste,/De nous rendre les Bourbons..." (Long live Alexander/Long live this king of kings!/Without demanding anything/Without dictating his laws to us/This august Prince/Has a triple reputation/As a hero, as a righteous man/And for restoring Bourbons to us...).

- Fètis and the brothers Michaud briefly allude to Lays's career ending tranquilly, and to a serene old age spent singing for pleasure in provincial churches. On the contrary, Madame Quéruel (Chapter: L'idole déchue. 1815–1831, pp. 147–159), basing herself primarily on research conducted in the archives of the Opéra and the Conservatoire (to which she summarily refers in footnotes), comes to quite different conclusions, as related in the present article.

- Quéruel, pp. 147–8

- He was the son of Denis-Pierre-Jean Papillon de la Ferté, the former Intendant of the Menus-Plaisirs, guillotined during the Terror, who had protected Lays in the 1780s at the time of his quarrels with Dauvergne, and whose office his son had been granted under the Restoration.

- Quéruel, p. 149

- Quéruel repeatedly writes that Cherubini had recently been named director of both the Conservatoire and the Opéra, but her assertion appears to be entirely without foundation. He had instead been named surintendant of the Royal Chapel in 1814, had been elected a member of the Institut de France in 1815 (during the Hundred Days), and was later to become the first real director of the École royale de musique et de déclamation in 1822 (Marc Vignal, Dictionnaire de la musique italienne, Paris, Larousse, 1988; Italian edition consulted: Dizionario di musica classica italiana, Rome, Gremese, 2002, p. 47), after having been one of the Conservatoire's inspectors from its foundation in 1795, and having become an outstanding professor of the new École royale when it had replaced the Conservatoire in 1816. Cherubini's predecessor as head of the institution, François-Louis Perne, only had the title of "inspecteur général des études", and the actual direction was exercised by the Menus-Plaisirs du Roi. According to a contemporary Italian source, Cherubini might have retained the post of inspector even within the new institution (article: Luigi Carlo Zenobio Cherubini, in Serie di vite e ritratti de' famosi personaggi degli ultimi tempi, Milan, Batelli & Fanfani, 1818, article n. 51; accessible online at Google Books).

- Quéruel, pp. 148–151

- See, for instance, the theatre programmes published daily in the following Paris newspapers:

"La Renommée", 1819, numbers 16/18/39/42/44/58/76/78/83/85/92/95/99/101/108/110/138/141/148/150/159/160/162/164/167/171/174/176/178/185 (accessible for free online at Google Books);

"Le Drapeau Blanc, journal de la politique, de la littérature et des théatres", 1820, numbers 31/33/42/117/124/131/136/150/164 (accessible for free online at Google Books). - Grétry's opera remained highly popular throughout the first quarter of the 19th century: Castil-Blaze reports that Rossini was able to play whole passages from it by heart on the harpsichord (op. cit. above).

- And where he is reported to have already managed to go on tour in 1792/93 as part of a delegation from the Paris Opéra led by Gossec, and to have later taken up an engagement in April 1818 (Jacques Isnardon, Le Théâtre de la Monnaie, Depuis sa Fondation jusqù'à nos Jours, Brussels, Schott, 1890, pp. 83 and 151; accessible for free online at Internet Archive).

- Quéruel, pp. 151–153

- Racine's tragedy had already been given at the Opéra four years earlier, premiering on 8 March 1819, with the host theatre's company (included Lays himself) performing the choral and musical interludes written by Gossec, to which an excerpt from The Creation by Haydn was also added. An account of one of the performances can be found in The Journal of John Waldie Theatre Commentaries, 1799–1830, n. 29 (Journal 42), note from 15 March 1819 (available online at UCLA's eScholarship, edited by Frederick Burwick).

- Académie Royale de Musique. Représentation d'Athalie et du Rossignol pour la retraite de Lays.– Rentrée de Lafon au Théâtre-Français, "Journal des débats politiques et littéraires", 3 May 1823, pp. 1–4 (accessible for free online at Gallica – B.N.F.). Quéruel postdates this performance by exactly three years, to 1 May 1826, which leads her to misinterpret data and documents referring to the interval between the two dates.

- Theatre programme and Macedoine, "La Lorgnette", II, n. 598, 8 October 1825, pp. 1 and 4 (accessible for free online at Gallica – B.N.F.).

- By that time, Cinti-Damoreau had been singing Italian opera for several years in Paris, London and Brussels. Along with Rossini, she now began to transfer to the Opéra, where Le Rossignol was to remain in the repertoire "largely as a showpiece for [her]" (Benjamin Walton, Rossini in Restoration Paris: The Sound of Modern Life, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 238, note 60).

- Literally meaning a "gutter-jumper" or a "skip-kennel", the 'saute-ruisseau' was the lowest clerical assistant, a sort of errand boy or boy messenger, in French law firms (cf. Honoré de Balzac, Colonel Chabert; English translation by Ellen Marriage and Clara Bell accessible for free online at Project Gutenberg).

- Both the following quotations are taken from Quéruel, p. 157

- Theatre programme and Bigarrures, "Le Figaro, Journal non politique", I, n. 300, 20 November 1826, and n. 303, 23 November 1826, p. 3 (accessible for free online at Gallica – B.N.F.: 20 November; 23 November).

- Quéruel, pp. 158-9

- Quéruel, p. 162. Further evidence of the Lays family's long-lasting economic difficulties, is provided by "La France Musicale", which published the following brief notice in August 1858 (also the basis of the article by Aldino Aldini cited in the bibliography): "His Majesty the Emperor, having heard that the daughter of Lays, of the Opéra, was in a state of the greatest poverty, ordered Monsieur Mocquart, his chef de cabinet, to forward her some assistance."

- Reminiscences of Michael Kelly, Of the King's Theatre, and Theatre Royal Drury Lane (...), London, Colburn 1826, I, p. 289, (accessible for free online at Google Books). According to Kelly, however, Lays's greatest praise "was, that he was very unlike a French singer".

- op. cit.

- The baritone clefs, both the C-clef on the fifth line and the F-clef on the third line, had long since fallen into disuse and all basse-taille parts would be notated in the bass clef.

- Printed score: Anacréon, ou L'Amour Fugitif, Opéra ballet en deux actes, Paris/Lyon, Magasin Cherubini, Méhul, Kreutzer, Rode, Isouard et Boildieu/Garnier, s.d., p. 90 (accessible online at IMSLP). Cherubini had used bass clef notation for the part of Astor entrusted to Lays in Démophoon (1788), to take one example (printed score: Démophoon, Tragédie Lyrique en Trois Actes, Paris, Huguet, s.d., p. 45; accessible online at IMSLP).

- Printed score: La Vestale, Tragédie Lyrique en trois Actes, Paris, Pacini, s.d., p. 28 (accessible online at Gallica – BNF).

- Michaud, op. cit. In fact, he sang the role in 1793 in an interminable tripatouillage (a confused rehash) which involved a complete performance of the comedy by Beaumarchais interspersed with Mozart's arias, duos, trios and choruses retranslated into French (Félix Gaiffe, Le Mariage de Figaro, Amiens, Malfère, 1928, p. 129; accessible online at Gallica – BNF).

- This role is not mentioned by Pitou, but it is stated by different sources, such as, for instance, Lajarte (p. 318).

- Pitou omits to mention this role among Lays's, but refers to it elsewhere in his article on Ariane dans l'isle de Naxos (p. 49).

- Despite not being a title role, Jason is the male lead.

- The role erroneously indicated by Pitou (although with a question mark) is 'Un Spartiate', but the original libretto gives the title role of Pollux (cf. Castor et Pollux : tragédie-opéra en cinq actes, représentée pour la première fois sur le théâtre de l'Académie-royale de musique, le mardi 14 juin 1791, Paris, DeLormel, 1791; accessible online at Gallica – BNF).

- Despite not being a title role, Mars is the male lead (in fact the only male character).

- Despite not being a title role, Pluton is the male lead.

- A minor role not mentioned by Pitou (cf. original libretto, Atys, Tragédie Lyrique en trois actes, Représentée ..., Paris, de Lormel, 1780; accessible for free online at ebook-gratis Google).

- A minor role not mentioned by Pitou (cf. original libretto, Persée, tragédie lyrique, remise en 3 actes, Représentée pour la ..., Paris, de Lormel, 1780; accessible for free online at Gallica - B.N.F.).

- Pitou writes that Lays played "Curiace", but he is mistaken (see the original libretto: Les Horaces, Tragédie-Lyrique, en trois actes, mêlée d'intermedes. Représentée devant Leurs Majestés à Fontainebleau, le 2 Novembre 1786, Paris, Ballard, 1786; accessible for free online at Gallica – BNF).

- A new musical setting of a libretto first set by Salieri in 1786, in which Lays played the same role.

- Most of the music of this reworking of The Magic Flute was taken from Mozart, but some came from Haydn, and was assembled by Ludwig Wenzel Lachnith (Mark Everist, Music Drama at the Paris Odéon, 1824–1828, Berkeley (USA)/Londra, University of California Press, 2002, p. 172, nota 6, ISBN 9780520234451).

- An oratorio in three parts assembled by Lachnith and Christian Kalkbrenner from music by Mozart, Haydn, Cimarosa, Paisiello, Philidor, Gossec and Handel.

- The music of this one-act piece was taken from Mozart and Haydn and arranged by Henri-Montan Berton (Mark Everist, op.cit. supra).

- This role is not mentioned by Pitou (cf. original libretto, Les Dieux rivaux, ou Les Fêtes de Cythère. Opéra-ballet en un acte, À l'occasion du mariage de S.A.R Monseigneur le Duc de Berry, Paris, Libraire des Menus-plaisirs du Roi, 1816; a copy is kept at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France).

- This role is not mentioned by Pitou (cf. printed score, Les Jeux floreaux, Opéra en trois actes, Paris, Chez l'auteur, s.d.; accessible for free online at Internet Archive).

- This role is not mentioned by Pitou (cf. original libretto, Aladin, ou la Lampe merveilleuse, Opéra Féerie en cinq actes, Paris, Roullet, 1822; accessible for free online at Gallica – BNF).

Sources

- Aldino Aldini, Lays, "The Musical World", XXXVI, 33, 14 August 1858, pp. 518–519 (accessible online at Google Books)

- (in French) François-Joseph Fétis, Biographie universelle des musiciens et Bibliographie générale de la musique (Second edition), Paris, Didot, 1867, V, pp. 235–236 (accessible online at Google Books)

- Elizabeth Forbes, Lays [Lay, Lais], François, in Stanley Sadie (ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Grove (Oxford University Press), New York, 1997, II, pp. 1112–1113. ISBN 978-0-19-522186-2

- (in French) Adolphe Jullien, 1770–1790. L'Opéra secret au XVIIIe siècle, Paris, Rouveyre, 1880 (accessible online at Internet Archive)

- (in French) Théodore Lajarte, Bibliothèque Musicale du Théatre de l'Opéra. Catalogue Historique, Chronologique, Anecdotique, Paris, Librairie des bibliophiles, 1878, Volume I (accessible online at Internet Archive)

- (in French) Joseph-François Michaud and Louis-Gabriel Michaud, Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne. Supplément. Suite de l'histoire ..., Paris, Michaud, 1841, LXIX, pp. 486–488 (accessible online at Google Books)

- (in French) Anne Quéruel, François Lay, dit Laÿs: la vie tourmentée d'un Gascon à l'Opéra de Paris, Cahors, La Louve, 2010. ISBN 978-2-916488-37-0

- Spire Pitou, The Paris Opéra. An Encyclopedia of Operas, Ballets, Composers, and Performers – Rococo and Romantic, 1715–1815, Westport/London, Greenwood Press, 1985. ISBN 0-313-24394-8

- This page contains material translated from the equivalent article in the Italian Wikipedia