Fort Kearny (Washington, D.C.)

Fort Kearny was a fort constructed during the American Civil War as part of the defenses of Washington, D.C. Located near Tenleytown, in the District of Columbia, it filled the gap between Fort Reno and Fort DeRussy north of the city of Washington. The fort was named in honor of Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny of the Union Army, who was killed at the Battle of Chantilly on September 1, 1862.[1] Three batteries of guns (Battery Rossell, Battery Terrill, and Battery Smead) supported the fort, and are considered part of the fort's defenses.

| Fort Kearny | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Civil War defenses of Washington, D.C. | |

| Tenleytown, District of Columbia | |

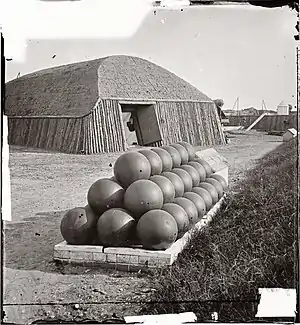

An ammunition magazine similar to those built at Fort Kearny. | |

| Coordinates | 38.955254°N 77.066098°W |

| Type | Earthwork fort |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1862 |

| Built by | 15th New Jersey Voluntary Infantry Regiment and the United States Army Corps of Engineers |

| In use | 1862–1865 |

| Materials | Earth, timber |

| Demolished | 1866 |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

| Garrison information | |

| Garrison | Two companies, 7th New York Heavy Artillery Regiment |

Construction and operation

Construction of the fort began in the summer of 1862, as a result of the discovery that the guns of Fort Pennsylvania (better-known as Fort Reno) and Fort DeRussy could not adequately cover the hilly terrain between Rock Creek and the Rockville Turnpike. To fix the situation, an intermediate fort was built to cover the dead ground. This fort would become known as Fort Kearny.

On September 4, 1862, the 15th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry Regiment was bivouacked adjacent to the hill selected for the fort and was assigned to do the initial construction work.[2] The name Fort Kearny was selected "in honor of the gallant General who had fallen at the hour of our entrance into Washington."[2] The Regiment was "also engaged in slashing timber, working on new military roads and throwing up embankments."[2] The area surrounding the fort was described as "naturally beautiful" but had been spoiled by war, "the trees for miles around were cut down, and the hills were denuded of even small brush, that the oversight might be without obstruction. Acres were covered with the abatis made of the fallen trees, the houses were deserted, and miles of fences burned."[2] With the construction of the fort completed, the men of the 15th Regiment assisted in mounting the guns. Finally relieved by the arrival of 200 contrabands from North Carolina, the 15th NJVI left Fort Kearny on 29 September 1862.[2]

.jpg.webp)

Construction proceeded slowly, hampered by a lack of workers. In December, the 113th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment was ordered to assist in the construction of the fort. Reports indicated that "of the 150 men that reported only 50 did any work."[3] Despite setbacks like these, by Christmas 1862, reports discussed the disposition of newly built Fort Kearny and several supporting field batteries that were constructed in order to cover blind approaches to the fort.[4] That report described Fort Kearny as "occupying an excellent position, [and] a necessary connecting link between Forts Pennsylvania and De Russy. It sees well the upper valley of Broad Branch, and crosses its fires with those of Forts Pennsylvania and De Russy and intermediate batteries upon the dangerous heights in front. It has a powerful armament, and is provided with ample magazines and bomb-proofs, and is well adapted to its location. A field battery, just across Broad Branch, has been built to sweep part of the ravine immediately in front of Fort Kearny; otherwise unseen."

The battery, later known as Battery Rossell,[5] provided space for eight field guns and a strong powder magazine. The battery was named in honor of Major Nathan B. Rossell of the 3rd U.S. Infantry, who was killed on June 27, 1862, at the Battle of Gaines' Mill.[6]

In 1864, the fort was garrisoned by two companies of the 7th New York Heavy Artillery Regiment, commanded by Major E. A. Springsteed. A May 1864 report on the defenses of Washington counted 298 soldiers in the fort's complement and stated that the garrison was of full strength. Despite this fact, deficiencies were found in the capability of those soldiers, whose drill was recorded as "indifferent," and that "improvement [was] needed."

In contrast, the physical properties of the fort were found to be fully capable. The same inspection found three 24-pounder siege guns, three 32-pounder barbette guns, one 5-inch siege howitzer, and three 4-inch rifled guns. In addition, the powder magazine was found to be "dry and in good order" and the ammunition as a whole, "[in]full supply and serviceable."[7]

Firepower and Dimensions

The number of guns and the current condition of Fort Kearny and its supporting batteries are as follows:

- Battery Terrill – 7 guns. Remnants located north of Fort Kearny, at 3001 Garrison Street on the grounds of the Peruvian Embassy. No marker.

- Fort Kearny – 11 guns. Located between Forts Reno and DeRussy, at 4900 30th Place. (320-yard perimeter) No remains, no marker.

- Battery Rossell – 8 guns. Located between Forts Reno and Kearny, at Fessenden Street and Connecticut Ave. No remains, no marker.[8]

Battle of Fort Stevens

In July 1864, Confederate forces under the command of Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early mounted a diversionary attack on the ring of forts defending Washington, D.C. in an attempt to relieve the pressure on Gen. Robert E. Lee, whose army was under pressure at Petersburg, VA. Early's Second Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, took up positions in the District, with Breckenridges's Corps located at (modern day) Friendship Heights, Early's Headquarters near (modern day) Chevy Chase, Gordon's Corps stretching across the hills near (modern day) Chevy Chase Village and (modern day) Upper Chevy Chase, and D. H. Hill occupying the area near (modern day) Silver Spring, MD.[9] His supporting Cavalry Artillery was positioned near (modern day) Westbrook, Maryland.[9] Though Fort Kearny itself did not come under direct fire from Confederate forces, at the time it was not certain that the Southern soldiers would not attempt to slip through the American lines in the hilly terrain near Tenleytown.

On July 11, the 22nd Regiment of the Veteran Reserve Corps, commanded by Lt. Col. A. Rutherford, began taking up positions in the rifle pits and trenches in front of the fort.[10] At 7:30 p.m., the Confederate forces of Early's force were seen entrenching north of the Fort Reno-Fort Kearny-Fort DeRussy line.

Accordingly, six companies of the 22nd Regiment were released from their entrenchments and ordered to reinforce the line of Union skirmishers that lay to the north of the fortifications. At 6 a.m. on the morning of July 12, these companies were ordered to advance northward. Doing so, they cleared out a pocket of Confederate sharpshooters that had established themselves on a nearby hilltop and who had been harassing the Union forces overnight. By 7:00 a.m., the 24th regiment of the Veteran Reserve Corps arrived at Fort Kearny to relieve the remaining companies of the 22nd, which were dispatched northward as reserves for the first six companies, which had already advanced two miles north of Fort Kearny.[10]

Those few Confederate sharpshooters would mark the closest advance of any recognized Confederate force to the guns of Fort Kearny. The majority of the fighting would take place to the north and east, near forts Stevens and DeRussy.

The 15th New Jersey Volunteers Return to Fort Kearny and the Defenses of Washington, D.C.

On July 9, 1864, the 15th NJVI, the builder of Fort Kearny, along with the rest of the 1st and 2nd Divisions of the 6th Corps, Army of the Potomac, were withdrawn from the siege of Petersburg, VA and ordered to board steamboats on July 11 at City Point, VA, to sail up the Chesapeake "on our way to Maryland as usual... earlier than in '62."

On the evening of July 11, General Early seized the opportunity for a dash into the city. "There was no adequate force to withstand him. Some thousands were gathered, it is true; the odds and ends of dismounted cavalry regiments, and the scrapings from the convalescent camp, together with a thousand or two men from the Quartermaster's Department...With no organization and without discipline, they were hardly better than an armed mob."[2] Authorities in Washington held little hope that the city would not be captured.[2]

But Early hesitated. "Before him was the greatest prize of the war, and in full sight of his troops rose high the dome of the capitol...he paused a night, and his magnificent opportunity was gone."[2]

On July 12, at 11 a.m., the 15th NJVI dropped anchor at "the Sixth Street Wharf in Washington City" (Modern day Washington Navy Yard) where they were "welcomed by crowds of citizens and officials, who received us as deliverers from a great peril. The arrival brought joy to Washington." [2] From there they, along with the other regiments of the 1st and 2nd Divisions, marched up 6th Street, turned onto 7th Street and on to the "7th Street Road". They marched with colors flying past cheering citizens who hung flags and waved handkerchiefs until they reached Columbian College Hospital (modern day George Washington University Hospital). "Soon we heard the booming of canon before us, and quickly, at the word, fell into ranks, and with accelerated pace hurried toward the scene of action."[2] They were ordered to proceed to Fort Massachusetts (Fort Stevens) to meet General Early's invaders.[2]

"It was about four p.m. when the guns of Fort Stevens opened upon the enemy stationed with the grounds of the Rives house...the first brigade of (the 2nd) Division was on picket, but the assaulting brigade (Wheaton's) passed through, and pressing up a rising ground, carried it. The enemy fell back to a stronger position on a second ridge."[2] The assault on this ridge resulted in 300 Union casualties and about the same number for the Confederates.[2]

"At dusk Early threw out a picket line. After this feeble demonstration, he began his retreat under cover of night. On the 13th of July the pursuit began. The 15th NJVI left Fort Stevens at 4 p.m. at the head of their Division, passing to the "rear of Forts de Russy, Kearney, Reno, and Pennsylvania. We thus passed over ground with which the Fifteenth was familiar...Fort Kearney looked much as it did when we left it, with only a fuller complement of guns, bomb-proofs, and connections with other works. Very comfortable barracks had been built for the occupation of any troops that might garrison it."[2]

"The next day he (Early) crossed the Potomac River at Edward's Ferry and this remarkable episode of the war came to and end."[2]

In the wake of the Confederate assault on the Washington defenses, a new report was released containing recommendations on improvements to the forts defending the city. In regards to Fort Kearny, the only suggestion involved the addition of four field guns to Battery Terrill, one of the subsidiary batteries that protected enfiladed approaches to the fort.[11]

Post-War Use

After the surrender of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865, the primary reason for manned defenses protecting Washington ceased to exist. Initial recommendations by Col. Alexander, chief engineer of the Washington defenses, were to divide the defenses into three classes: those that should be kept active (first-class), those that should be mothballed and kept in a reserve state (second-class), and those that should be abandoned entirely (third-class). Fort Kearny fell into the second-class category.[12] As budget cuts mounted, however, Fort Kearny, which had been scheduled to be mothballed, was abandoned and the land sold. Today, no trace of the fort remains in what is the primarily residential neighborhood of Forest Hills, between Fort Reno Park and Fort DeRussy in Rock Creek Park.

Location

A comparison of the topographical map prepared for General John G. Barnard Chief Engineer, Army of the Potomac,[13] and a topographical map of modern Washington pinpoints the location at the 4900 block of 30th Place. Using the contour of Fort Kearny drawn by Robert Knox Sneden[14] in 1862, the position of the fort can be readily determined.

See also

References

- U.S., War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 Volumes (Washington, DC: The Government Printing Office, 1880-1901) I, 25, Part 2 (serial 40), 140-41

- Alanson, Haines (1883). History Of The Fifteenth Regiment New Jersey Volunteers. New York: Jenkins & Thomas, Printers. pp. 14–17, 222–227. ISBN 0-942211-52-9.

- Record Group 393, Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Preliminary Inventory 172, Part 2, 3d Division, 3d Army Corps, Entry 6770, Letters Received, September–October 1862, W.C. Gunnell, per James A. Brown, Clerk, Headquarters, Engineer Department, Defenses Of Washington, to Col. Haskin, Dec. 16, 1862

- Official Records, I, 21 (serial. 31), 902-16

- Official Records I, 25, Part 2 (Serial 40), 186

- General Orders, No. 83. War Department, Adjutant General's office, April 1, 1863.

- Official Records I, 26, Part 2 (Serial 68), 883-97.

- "District of Columbia Forts". www.northamericanforts.com. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- "Plan of the Rebel Attack On Washington, D.C., July 11th and 12th 1864". Library of Congress.

- Official Records I, 37, Part 1 (serial 70), 343-45

- Official Records I, 37, Part 2 (serial 71), 492-95

- Official Records (Serial 97) Series I, Volume XLVI, Part 3, 1130

- "Tour of the Civil War Defenses of Washington, D.C. - Sheet # 8 | Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- Sneden, Robert Knox (1862). "Union Forts On Maryland Shore". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Kearny (Washington D.C.). |