Fort Crèvecoeur (Netherlands)

Fort Crèvecoeur was a Dutch fortress near 's-Hertogenbosch. It is now a military exercise terrain.

| Fort Crèvecoeur | |

|---|---|

| Meuse, Netherlands | |

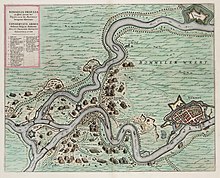

.jpg.webp) Fort Crèvecoeur from the Atlas van Loon, 1649. | |

Fort Crèvecoeur | |

| Coordinates | 51.736334°N 5.267067°E |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Dutch MoD |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1587 |

| Materials | earth |

First Fort Crèvecoeur

Eighty Years War

Fort Crèvecoeur was founded during the Eighty Years' War. In 1587 the main campaign centered around the Siege of Sluis in Zeeland. A smaller part of the States' army under Philip of Hohenlohe came in action near 's-Hertogenbosch. Hohenlohe first took the Loon op Zand Castle, and plundered some villages. He then made a ship bridge over the Meuse and started to besiege the Sconce of Engelen. The Spanish Netherlands therefore sent Claude de Berlaymont lord of Haultpenne to the area with 42 companies of foot and 25 squadrons of cavalry. He attacked Hohenlohe in order to lift the siege, but was defeated. Haultpenne himself was wounded, and on 14 July he died from his wounds in 's-Hertogenbosch.[1]

Hohenlohe then conquered the Sconce of Engelen, and razed it. On the place 'where the battle was fought' Hohenlohe somewhat later constructed a new strong fortification that was named Crèvecoeur.[1] The logic behind it was simple. The Dutch wanted to block any action from 's-Hertogenbosch to the Meuse, and in general the Republic was stronger on water. This made supplying a fortress on the Meuse easier than supplying a fortress on the Dieze at Engelen, where river transport could be blocked. The Spanish side reacted by rebuilding Fort Engelen. It seems that later the Spanish side reconquered Crèvecoeur.[2]

In 1590 the Dutch army reconquered Fort Crèvecoeur.[2] On 29 June 1593 a Spanish army under Count Mansfeld appeared before Crëvecoeur. Somewhat before that, Floris van Brederode, lord of Cloetingen, had marched into the fort with reinforcements. Now the Dutch built a dam across the Dieze, causing all the surrounding lands to flood, and Mansfeld broke off the siege.[3] 1594 started with the Dutch Republic attempting to surprise 's-Hertogenbosch, The attempt failed, but the subsequent Siege of Groningen (1594) succeeded.

Siege of 1599

On 4 May 1599 a Spanish army under La Barlotta crossed the Meuse between Kessel and Maren (east of Crèvecoeur) and invaded the Bommelerwaard. On 5 May a Dutch army under Prince Maurice moved to Zaltbommel. The Spanish then took Crèvecoeur after a short siege, and made a bridge over the Meuse. The Spanish then started a siege of Zaltbommel, which they abandoned on 3 June. However, the Spanish did found the Sconce Sint Andries, which controlled the Meuse and the Waal. Crèvecoeur was also expanded.[4]

Siege of 1600

In early 1600 the Walloon and German garrison at Fort Crèvecoeur numbered about 200 men.[5] The garrison of Fort Sint-Andries was 2,000 men strong. After the pay of some men in these garrisons fell 20 months into arrears and that of others for even longer, they mutinied in February 1600. On 16 February they seized their commanders and sent them to 's-Hertogenbosch.[6] Maurice, Prince of Orange tried to profit from this opportunity. About 20 March he collected some troops, and sent them up the Meuse from Dordrecht to Crèvecoeur. On 24 March 1600 Fort Crèvecoeur was handed to him by treaty. Out of the four companies that formed the garrison, two were allowed to leave for St-Andries. Of the other two, some ended their mutiny and left for 's-Hertogenbosch. Of the others a new company was formed to serve in the States' army.[7] On 8 May Fort Sint-Andries followed by a treaty that included a payment of 125,000 guilders to the losing garrison. Of the men that switched to the side of the republic, 11 companies were established.[8]

With Fort Crèvecoeur and Fort St Andries, the United Provinces reconquered an upstream part of the Meuse. Maurice added seven bastions to Fort Crèvecoeur. In 1601 Maurice besieged 's-Hertogenbosch, but could not take it due to frost.[8] In 1602 he was successful in the siege of Grave, adding another 30 km of the Meuse to his control. In 1603 he made another attempt to take 's-Hertogenbosch.

The name Crèvecoeur

The early 1600s were the years that the name Crèvecoeur surfaced in writing. Crève-coeur, literally means 'heart pain', and is a name that has been used for other fortresses as well. An older guess why this fortress was so named, was that it gave pain to the citizens of 's-Hertogenbosch, who were cut off from the Meuse by this fortress.[1] Crèvecoeur indeed cut off the city from communication upstream on the Meuse, but at the time the Dieze was a dead end. Other explanations could be that the fort almost permanently flooded the land around the city or that the Dutch used the fort to levy heavy taxes on shipping on the Dieze before they conquered 's-Hertogenbosch in 1629. Fort Crèvecoeur often seems to be depicted as a hamlet on old maps, but it never had any civilian population, even though it had a church.

The Twelve Years' Truce

During the Twelve Years' Truce (1609-1621) Fort Crèvecoeur was controlled by the republic. It hampered the recovery of 's-Hertogenbosch, because the flooding continued. The republic was prepared to negotiate an opening in the dykes near the fort. Negotiations failed in 1613, but succeeded soon after.[9] Meanwhile the Protestant religion was celebrated in the fort and in Engelen. The religion and associated charity lured many from 's-Hertogenbosch to visit these places.[10]

After the truce had ended, trade continued. However, the United Provinces did not allow ships to sail up the Dieze past Crèvecoeur. In 1622 they also started to levy one-third higher taxes on goods to and from 's-Hertogenbosch than on goods from other places in the Spanish Netherlands. These extra taxes ended only in 1625.[11]

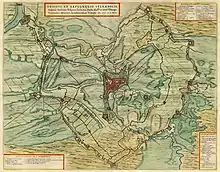

The conquest of 's-Hertogenbosch

During the first years after the truce, the Spanish appeared to have the upper hand after they took Breda in 1624. Somewhat later the Dutch took Oldenzaal in 1626 and Groenlo in 1627. In April 1629 the Dutch then started the campaign that would lead to the successful Siege of 's-Hertogenbosch. Just in time the commander of Crèvecoeur got orders to arrest some ships that were planning to bring supplies to the city.[12] On 30 April 's-Hertogenbosch was closed in. Now a fleet of supply ships was sent to deliver everything that was needed for the siege to Crèvecoeur. Its role as a supply hub for the siege was further strengthened by making a ship-bridge across the Meuse.[13] During the siege the fort had at least 18 cannon, but it was not in the front line.[14] After 's-Hertogenbosch had been conquered by the Republic, Crèvecoeur continued to guard the Dieze. West of it, near Bokhoven a warship guarded the Meuse towards Holland.[15]

Franco-Dutch War

During the Franco-Dutch War French troops under Turenne easily captured Nijmegen on 9 July, as well as Grave. On 14 July 1672 Turenne then closed in on Fort Crèvecoeur. On 16 July a bombardment from two batteries started. Later more batteries were added, and as the enemy approached the militia started to mutiny, leading to the surrender of the fortress on 19 July.[16] Nevertheless, 's-Hertogenbosch stood firm. In late 1673 the French left Crèvecoeur. Apart from the church and the commander's house, they destroyed everything as much as possible. They blew up the gunpowder magazine by igniting 500 pounds of gunpowder amidst its foundations.[17]

In light of this result the States General decided that the fortress was more of a threat than a defense for 's-Hertogenbosch, and decided to completely destroy the fortress.[18] This happened in 1674. Farmers from the vicinity of 's-Hertogenbosch were summoned to perform this work. This caused trouble, because it was far from their homes, and situated in the county of Holland. It was only the threat of prosecution that got it done. Of the first Fort, only the small church is left.

Second Fort Crèvecoeur

A Coehoorn design

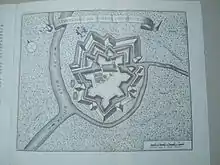

In 1701 the Dutch decided that a fortress was nevertheless needed at the mouth of the Dieze in order to control the inundations of 's-Hertogenbosch. A plan was made by Menno van Coehoorn. The high cost, and resistance by several land owners made that construction was severely delayed.

By 1735 a smaller version of the Coehoorn design was completed.[19] The fortress then had seven bastions named counter clockwise: Empel, Heel, Maase, Boeckhoven, Henriëtte, Engelen, Dies. It had two guard houses, some bomb free shelters, one big and three smaller gun powder magazines, a house for the commander, a house for the staff operating the lock, a harbor with water gate, and the church that remained from the first fortress. The idea was that the Dieze would flow freely around the fort, but that in times of war, the Dieze would be blocked, and shipping would use the locks inside the fort.[20]

War of the Austrian Succession

During the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) the locks and Dam of Crèvecoeur were put into action after Flanders was lost to the French in 1746. That same year the locks in the Dieze that flowed through the fort were completed,[18] and shipping was led through the fortress till the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748). At first ships could not use the canal through the fort because of strong currents.[21] This was solved later on.[22] From a military perspective the measures were quite effective. Surrounded by water on all sides 's-Hertogenbosch 'resembled an island'.[23]

Fort Crèvecoeur was later described as having barracks for the troops, a house for the commander, a church and a gun powder magazine. The church was still the same church and served as an arsenal. The gun powder replaced that which the French had blown up in 1673.[23]

Siege of 1794

In mid 1794 the garrison of Fort Crèvecoeur amounted to 104 men and 30 gunners. On 16 September these were reinforced by the arrival of the Hessen-Darmstad fusileers, bringing the total garrison to 462 men. The fort had 2 24-pdr cannon, 9 12-pdr and 9 6-pdr and 14 3-pdr cannon, as well as 20 mortars. There was sufficient gunpowder.[24] On 22 September 's-Hertogenbosch was closed in. The French wanted to take Crèvecoeur, because it controlled the inundations around 's-Hertogenbosch. The fort was only weakly defended by commander Colonel N.C. Tiboel.[25] After a short siege it was handed over by treaty in the evening of 27 September 1794.

Later Colonel Tiboel was court-martialed. He was acquitted after explaining that the fortress had not been properly prepared. There were no gabion baskets, nor other material to make gun ports, i.e. no people able to handle these. The cannon were not in working condition, and carriages could not be repaired. For the heavy muskets there were enough bullets, but cartridges were missing. Loading sticks to use these muskets with loose powder were missing. Furthermore there was flour, but no oven to make bread. Last, but not least, the soldiers had to sleep in the open air.[26] Others claim that the fort did have cover for the soldiers, and questioned the speedy surrender, as well as the abilities and political opinions of the commander.[27]

The surrender of Fort Crèvecoeur enabled the French General Pichegru to open the lock. This somewhat lowered the inundations around the city, but ideas that these were simply drained by opening the lock at Crèvecoeur are false. The locks at the fort were crucial for hastening the inundation. However, most of the inundations were caused and controlled by stopping the Dommel and Aa in 's-Hertogenbosch itself (cf. the siege of 1629). If the inundations were already sufficient, the only effect of opening the lock at Crèvecoeur was that it opened up a way to attack the citadel from the north. [28]

Next the fortress was neglected for decades. On 14 December 1813 the fortress was surrendered by the French.

Early nineteenth century

A whole new renovation plan was proposed in 1815, but it was not executed. After the Belgian independence some funds were allocated. In 1842 some urgent maintenance was done. From 1858 to 1860 extensive renovations to the fortress took place. Total cost amounted to 55,500 guilders.

Last phase as a fortress

In 1870 the recently renovated Fort Crèvecoeur was mobilized on account of the Franco-Prussian War. In 1874 two batteries were added to the east, because the dyke of the new Utrecht-Boxtel railroad hindered the fortress' guns. In 1890 the Dieze canal was opened, which moved the mouth of the Dieze some kilometres to the west. It severely limited the ability of the fortress to control inundations in the area. On 28 May 1926 the government ended the status of Fort Crèvecoeur as a fortress. In 1937 two eastern bastions and the eastern moat were eliminated to create the national road from Hedel to 's-Hertogenbosch, which used the Hedel Bridge, opened in the same year.

World War II

In May 1940 the 159th AA battery of the 9th machine gun company was located at the fortress. Later in 1940 the Germans flattened Bastion Hedel in order to use a ship bridge instead of the blown-up Hedel Bridge. In 1944 the German army placed some FLAK batteries. On 8 December 1944 Fort Crèvecoeur was conquered by the Canadians.

Current Situation

Training grounds for the engineers

After World War II the Dutch corps of engineers came to use the grounds. The canal and locks were filled up. A small harbor remains from the canal, and another small harbor is situated to the east. During the Cold War, the fortress was equipped to quickly make a pontoon bridge across the Meuse if the Hedel Bridge was destroyed. To create cover for the long traffic jams that could be expected in such circumstances, the terrain was allowed to grow wild. This wilderness was cut down in the early nineties, and now the fort is an open space. Now and then there are plans for a restoration of the fortress.

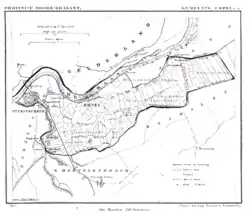

Weir and fish ladder

The Dieze now splits right before the fortress and then continues south and west of it. This is kind of the same situation that existed in the early eighteenth century. However, the branch that used to flow through the fortress is now a dead end. Therefore all the water now flows west of the former fortress. Immediately after the split, there is a weir. It is a rather modest construction. In spite of the Dieze Canal being much wider, this weir controls most of the water level in the east of North Brabant.

South of the weir a meandering water suggests an old bed of the Dieze. This is actually a fish ladder, built in 2012.

Further reading

- H.J.Bruggeman en Wim van den Oord, 1992, Rondom Crèvecoeur.

References

- Bachiene, W.A. (1777), Beschryving der Vereenigde Nederlanden (in Dutch), IV

- Freiherrn von Gross, A.G. (1808), Historisch-militärisches Handbuch für die Kriegsgeschichte der Kriegsgeschichte der Jahre 1792 bis 1808 (in German), I, Amsterdam, im Verlage des Kunst- und Industrie- Comptoirs

- Heurn, J.H. (1776), Historie der stad en Meyerye van 's-Hertogenbosch (in Dutch), II

- Heurn, J.H. (1777), Historie der stad en Meyerye van 's-Hertogenbosch (in Dutch), III

- Heurn, J.H. (1778), Historie der stad en Meyerye van 's-Hertogenbosch (in Dutch), IV

- Hupkens, Ed (2012). "Fort Crèvecoeur: een verwaarloosde vesting" [Fort Crèvecoeur: a neglected fortress]. Bossche Encyclopedie (in Dutch). Ton Wetzer.

- van der Kemp, C.M. (1843), Maurits van Nassau (in Dutch)

- Kesman, J.H. (1835), "Herinneringen uit het Beleg van 's Hertogenbosch in het jaar 1794" (PDF), De Militaire Spectator (in Dutch) (11): 231–242

- van Sasse van Ysselt, A. (1899), "Dagregister", Taxandria; Tijdschrift voor Noordbrabantsche Geschiedenis en Volkskunde (in Dutch), Jan A.G. Juten, Bergen op Zoom: 207–213, 241–279

Notes

- Heurn 1776, p. 177.

- Heurn 1776, p. 192.

- Heurn 1776, p. 201.

- Heurn 1776, p. 231.

- van der Kemp 1843, p. 240.

- Heurn 1776, p. 245.

- van der Kemp 1843, p. 241.

- Heurn 1776, p. 249.

- Heurn 1776, p. 329.

- Heurn 1776, p. 331.

- Heurn 1776, p. 374.

- Heurn 1776, p. 405.

- Heurn 1776, p. 406.

- Heurn 1776, p. 429.

- Heurn 1776, p. 529.

- Heurn 1777, p. 189.

- Heurn 1777, p. 226.

- Hupkens 2012.

- Heurn 1777, p. 11.

- Heurn 1778, p. 13.

- Heurn 1778, p. 91.

- Heurn 1778, p. 82.

- Bachiene 1777, p. 506.

- van Sasse van Ysselt 1899, p. 212.

- van Sasse van Ysselt 1899, p. 250.

- Kesman 1835, p. 233.

- Freiherrn von Gross 1808, p. 59.

- Freiherrn von Gross 1808, p. 60.