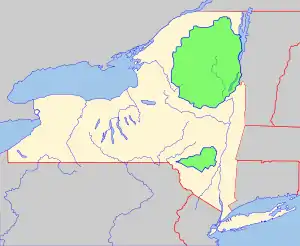

Forest Preserve (New York)

New York's Forest Preserve, comprises almost all the lands owned by the state of New York within the Adirondack and Catskill parks. It is managed by the state Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). Of the 4.7 million acres(19,000 km2) of land in the state maintained by DEC, nearly 3 million (12,000 km2) are considered to be Forest Preserve.[1]

These properties are required to be kept "forever wild" by Article 14 of the state constitution, and thus enjoy the highest degree of protection of wild lands in any state. It is thus necessary to amend it in order to transfer any of these lands to another owner or lessee. Currently there are more than 2.6 million acres (11,000 km2) of Forest Preserve in the Adirondacks and 287,514 acres (1,164 km2) in the Catskills.

While today the Forest Preserve is valued largely as a conservation measure, its establishment in the 19th century was motivated primarily by economic considerations. Gradually its inherent worth as a nature preserve came to be seen, as it became a draw for recreation and tourism. A later amendment to Article 14 also made the lands important parts of water supply networks in the state, particularly New York City's, by allowing 3% of the total lands to be flooded for the construction of reservoirs.

Origins

Adirondacks

During the years after the Civil War, the state's business community began to fear that unchecked logging in the Adirondacks could, through erosion, silt up the Erie Canal and eliminate the state's major economic advantage. They were informed by George Perkins Marsh's seminal 1865 book, Man and Nature, which made the connection between deforestation and desertification.

Five years afterward, surveyor Verplanck Colvin beheld the Adirondacks from the summit of Seward Mountain during his mission to map the region. The idea of preserving the lands in some sort of park occurred to him then and there, and after he returned he wrote to his superiors in Albany that action needed to be taken to prevent that kind of despoliation. They appointed him to a committee to study the problem.

In 1882, the businessmen began lobbying the legislature in earnest, and were rewarded three years later with the passage of the Forest Preserve Act, which provided that no logging would be allowed on state-owned land.

Catskills

Later that year, Ulster County's representatives in the Assembly were trying to get the county out of a crushing property tax debt a court had ruled they owed the state. Their solution was to convey some of the land on which they owed the taxes, mostly around Slide Mountain to the state.

The Catskills had actually been considered when the Forest Preserve legislation was first passed, but Harvard botanist Charles Sprague Sargent had visited them and reported back to the legislature that it was not worth the effort as its streams did not appreciably affect the state's navigable waterways. However, an amended version of the bill was passed, after many deals and compromises among members, that added lands in Ulster, Sullivan and Greene counties to those eligible for Forest Preserve status.

One side effect of this deal is that the state pays all local and county property taxes on the Forest Preserve as if it were a commercial landowner. This has helped many local governments remain solvent as they have very little economic assets other than forest resources.

Article 14

To manage the land, the state had created a Forest Commission, making New York second only to California in having a state-level forestry agency. Most of its members were either openly or covertly connected to timber interests, however, and routinely approved dodges around the legislation to make sure logging would continue. In 1893 the legislature retroactively approved many of these practices by giving the commission the right to sell timber from the lands and trade them as it saw fit.

It seemed the Forest Preserve now existed only on paper. But the following year New York held a constitutional convention, and the language of the law was written into the new state constitution with added words to close every loophole the Forest Commission had found.

This section, Article 7 of the 1894 constitution (which was later changed to article 14), is often referred to as the "forever wild" section even though those two words do not appear next to each other in the text.

The lands of the state, now owned or hereafter acquired, constituting the forest preserve as now fixed by law, shall be forever kept as wild forest lands. They shall not be leased, sold or exchanged, or be taken by any corporation, public or private, nor shall the timber thereon be sold, removed or destroyed.

Since amending New York's constitution is a deliberately cumbersome process that requires the approval of both Assembly and Senate in successive sessions of the legislature, followed by public approval at the next general election, this put a severe damper on any efforts by the Forest Commission to placate the loggers while still claiming to be honoring the law.

Nonetheless, they would try. The new provision barely survived an attempt to gut it two years later when they again prevailed upon the legislature to approve an amendment requiring the state to "manage the land in accordance with sound timber management principles." Voters resoundingly rejected it, however, and the principle of a "forever wild" Forest Preserve has remained inviolate in New York State to this day.

Since then, over 2,000 amendments to Article 14 have been introduced in the legislature. Of those, only 28 have made it to the ballot, and only 20 have passed. Many of those have been otherwise routine land transfers that enabled the construction or expansion of public cemeteries or airports. Others have allowed for the construction and continued maintenance of reservoirs and highways. The most significant change was a pair of amendments that created the ski centers at Belleayre in the Catskills and Gore and Whiteface in the Adirondacks. The latter includes a toll road to the summit as well.

Subsections were later added to allow the construction of reservoirs and make certain that use of the land remained free to the public beyond any reasonable fee the state could charge for a particular activity.

Acquisition of new Forest Preserve land

Blue Line

In 1902, when Article 14 was more a matter of settled law, the legislature realized it had to delimit where Forest Preserve would be acquired. Accordingly, that year the Adirondack Park was defined in terms of the counties and towns within it.

Two years later, the Catskill Park was defined. Instead of just declaring certain towns to be within the park, however, the legislature also used old survey tract boundaries, streams and railroad rights-of-way to clarify where it would be seeking land in the future.

The park boundaries became known as the Blue Line since they were drawn, as they have been ever since, in blue ink on state maps.

Methods of land acquisition

While many of the original holdings came from tax foreclosures, over time the state bought huge tracts, aided by bond issues approved by the public. One in the late 1920s proved to be of particular value as the state was able to acquire a great deal of property at minimal prices due to the Great Depression. At that time the state's Parks Council bought the land and left management to the then-Conservation Commission.

The state could also theoretically use its power of eminent domain to acquire Forest Preserve, but in practice it has rarely resorted to this.

For the time being, the state is not seeking to expand the Forest Preserve as actively as it has in past years, since many of the most desired properties have been acquired. However, it remains publicly committed to working with any willing seller.

Land classifications within the Forest Preserve

Ecological and environmental awareness grew in the later years of the 20th century. Recreational use of the Forest Preserve began to rise to new levels, and newer methods of outdoor recreation became popular. These two factors led to a widespread realization that it was no long enough to simply rely on the language of Article 14 and the state's Conservation Law (as it was called at the time) and the court decisions and administrative opinions that relied on them.

The Conservation Department became DEC in 1970. One of its new tasks was to implement more contemporary land management practices. But administration of the state land in both parks was (and still is) split between different regional offices, and it was hard to get them both following the same principles since they did not communicate much.

There was also no serious planning involved. New trails were created, or allowed to be created by outside parties, with little thought to their environmental impact or regional role. Camping was permitted anywhere, and some of the sensitive alpine environments in the Adirondack High Peaks were showing the effects.

Two temporary state commissions set up to consider the future course of the Adirondacks and Catskills in the early 1970s both strongly recommended that master plans be created for state lands in both parks. They also called for classifying the large tracts of state land as either wilderness areas or wild forest, depending on the degree of previous human impact and the level of recreational use they could sustain. Both of these were ultimately adopted, along with intensive use area and administrative use area designations for smaller parcels.

In the Adirondacks, several additional classifications exist due to the more diverse character of lands in the extensive area of the park: primitive area; canoe area; travel corridor; wild, scenic, and recreational rivers; and historic area.

Wilderness area

New York State's wilderness areas are managed in a way essentially similar to their federal counterparts. Wilderness areas are those judged to have been far more affected by nature than humanity, to the extent that the latter is practically unnoticeable. As a result, the Forest Preserve's wildernesses boast extensive stands of virgin forest.

No powered vehicles are allowed in wilderness areas. Recreation is limited to passive activities such as hiking, camping, hunting, birding and angling which are themselves subject to some further restrictions to ensure that they leave no trace for later recreationists. Special restrictions were recently imposed to limit impact on the largest and most popular wilderness area, the High Peaks Wilderness Complex in the Adirondacks.

Powered equipment, such as chainsaws, may be necessary to keep trails open but such use is permitted only with the express written authorization of the DEC commissioner.

Structures other than those that facilitate recreational use, such as bridges and lean-tos, are generally not allowed, either.

The only significant difference between New York's wilderness policy and the federal government's is that the former limits the classification to contiguous parcels of at least 10,000 acres (40 km²), instead of 5,000 (20 km²).

Currently, approximately 1.1 million acres (4,400 km²) of the Forest Preserve is designated as wilderness.

Wild forest

While retaining an essentially wild character, Wild Forests are those areas which have seen higher human impact and can thus withstand a higher level of recreational use. Often these are lands which were logged heavily in the recent past (sometimes right before being transferred to the state).

They might best be described as wildernesses where, within limits, powered vehicles are allowed. The wide roads left behind by logging operations make excellent trails not only for foot travel but for horses, snowmobiles, and cross-country skiing as well. Hunters prefer to seek game in wild forests because they can use cars or trucks to transport their kills out.

Not all vehicle use is permitted, however. Mountain bikers and all-terrain vehicle enthusiasts have been lobbying DEC to allow them use of some Wild Forest trails in recent years. As of 2005 it appears that the former may be allowed to use some trails, particularly the old roads that lead to fire towers in both parks, DEC and most other users feel that even Wild Forest trails could not absorb the impact of ATVs.

Powered equipment may be used to maintain trails and roads within Wild Forests.

In the Catskills, it has long been informal DEC policy to treat all Wild Forest lands above 3,100 feet (944.9 m) in elevation as de facto wilderness. A proposed update to the master plan for the park would not only make this formal but extend the limit to 2,700 feet (823 m).

Intensive use area

Intensive Use areas are places like state campgrounds or "day use" areas (more like a small public park) without camping. There may be designated campsites, picnic tables, charcoal grills, public restrooms and shower facilities and swimming areas with lifeguards. A fee is charged between May 1 and October 1 for most of these activities, and sometimes just for entering the area. DEC manages 45 campgrounds in the Adirondacks and 7 in the Catskills, for a total of 52 (public campgrounds elsewhere in New York are under the authority of the state parks).

The state's three ski areas — Belleayre Mountain in the Catskills and Gore mountain and Whiteface Mountain in the Adirondacks — also fall under this classification as well.

There are five day-use areas in the Adirondacks and one (so far) in the Catskills.

Administrative use area

This classification applies to a limited number of DEC-owned lands that are managed for other than Forest Preserve purposes. It covers a number of facilities devoted to research, some prisons, and state fish hatcheries in both parks.

Most Administrative Use areas are located close to public roads and are generally in fairly developed areas of their respective parks.

Land classifications in the Adirondacks

The categories below are specific to Adirondack Forest Preserve lands; they are not used in the Catskills.

Primitive area

A Primitive Area is one that has much the same characteristics as wilderness area, but has some significant obstacles to receiving that status. It may have structures that cannot easily be removed within a given timeframe, or some other existing use that would complicate a wilderness designation. The designation is also applied to areas of less than the minimum area that have environments sensitive enough to require wilderness-level protection.

For most practical purposes, then, there is no difference between a primitive area and a wilderness area.

Canoe area

Canoe Areas are lands with a wilderness character that have enough streams, lakes and ponds to provide ample opportunities for water-based recreation.

Since they are relatively flat, and the severity of a typical Adirondack winter ensures that most bodies of water will freeze over, they are excellent places to snowshoe and cross-country ski in that season as well.

Currently, the Saint Regis Canoe Area is the only such designated area in the park.

Wild, scenic, and recreational rivers

There are three levels of classification for Forest Preserve lands around streams, depending on their levels of impoundment and public access.

- Wild rivers, or sections of rivers, are relatively inaccessible except by foot or horse, have no impoundments and are generally undeveloped except for foot bridges.

- Scenic rivers, or sections of rivers, may have limited road access, some low-impact human use and can be impounded by log jams.

- Recreational rivers, or sections of rivers, are readily accessible by road or rail and may be or have been at some point in the past developed or impounded by artificial means.

Historic area

These are the sites of buildings owned by the state that are significant to the history, architecture, archaeology or culture of the Adirondacks, those on the National Register of Historic Places or carrying or recommended for a similar state-level designation.

Travel corridor

This classification refers primarily to lands not really considered for recreational use but for those sections of the Forest Preserve constituting the right-of-way and roadbed for sections of the Adirondack Northway, other public highways in the Park, the Remsen-to-Lake Placid Adirondack Scenic Railroad right-of-way and lands immediately adjacent to and visible from them. It results from a mid-1960s amendment to Article 14 that allowed such road construction and maintenance, primarily to complete the Northway.

Forest Preserve lands outside the parks

State law also allows DEC to classify land it acquires outside the Blue Lines, but in counties partially within the parks, as Forest Preserve. These have usually been small detached parcels rarely organized into larger, named units. Article 14's prohibition on further sale or transfer still applies, although the state may allow the timber on these lands to be harvested.

Controversies

While no one talks seriously of rescinding Article 14 anymore, that hasn't stopped some residents of the state from publicly chafing at its strictures. This is particularly common in the Adirondacks, since the many vast tracts of land under Forest Preserve protection limit economic opportunities in a region where it has always been a struggle to earn a living. Melvil Dewey sounded a common theme in the early 20th century when, advocating another constitutional amendment to open up more land to logging, he complained that the current situation only benefited "the bugs," referring to the blackfly infestations that keep many residents indoors during daylight hours in the early summer.

Fire towers

In the late 1990s a DEC forester writing a management plan for the Balsam Lake Wild Forest in the Catskills recommended that the fire tower on top of the similarly named mountain be removed and dismantled as nonconforming. He did this in the hope that someone would step forward to save not only this but the other four fire towers on state land in the Catskill Park. At that time the towers had not been used for fire control for years, and some were no longer safe to climb.

Someone did, and after a matching challenge to raise the money, DEC was not only able to exempt them from removal on the grounds that they contributed to the public's understanding of the Forest Preserve, but repaired all of them as well. In 1997 they were added to the National Register of Historic Places. All five and their accompanying cabins have been or will be converted into small interpretive centers, with displays identifying nearby peaks.

Similar campaigns were undertaken in the Adirondacks, and hikers can now even receive a patch for their backpacks by visiting all the Forest Preserve firetowers. DEC even built a new trail to the tower on Red Hill in the Catskills, as the road to it crosses private land whose owner will not permit the public to cross it.

The only fire tower still a subject of dispute is on Hurricane Mountain in the Adirondacks, since unlike the others it is within a Primitive Area classified by the DEC as the Hurricane Mountain Primitive Area. There has been speculation that the DEC would like to reclassify this 13,449-acre (5,443 ha) parcel into a Wilderness Area. Wilderness Areas are considered "untouched by man" and a firetower is viewed as a non-conforming structure. As such, the DEC wants it removed for this reason. However, residents of the area have been fighting to keep it since not only is it a popular and relatively easy hike, it is the only fire tower in the High Peaks region. The Hurricane Mountain fire tower is also the insignia of the Adirondack Mountain Club Hurricane Mountain Chapter.

Canisters

Also in the late 1990s, DEC, in its long-delayed management plan for the High Peaks Wilderness Complex, called for the removal of the canisters at the summits of the 20 High Peaks that lacked official trails but were nevertheless climbed frequently by the growing number of hikers seeking membership in the Adirondack Forty-Sixers.

Many members felt these were an integral part of the club's identity and wanted to keep them. But in summer 2000, the 46ers' board decided to remove them as they did not feel it would be worth pursuing a lawsuit to keep them, especially with little law on their side. Some members are still bitter about this decision since it was taken without consulting the group as a whole.

At the same time in the Catskills, however, the situation played out differently. The 1998 draft update to the Unit Management Plan for the Slide Mountain Wilderness Area, the Catskills' counterpart to the HPWC, similarly called for the removal of four canisters from that area.

Public comment, mostly from members of the Catskill Mountain 3500 Club, which maintains those canisters, persuaded DEC to compromise, accepting ownership of them and some design changes in exchange for keeping them as, like the fire towers, structures that enhanced understanding of the Forest Preserve. This change was later written into the 2003 draft update to the Catskill State Land Master Plan.

The different outcome is largely because the Catskills' more open forests mean that its trailless peaks actually are trailless, whereas it has been hard to say that of the Adirondack trailless peaks for some time now.

References

- "New York's Forest Preserve - NYS Dept. of Environmental Conservation". www.dec.ny.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-10.