Foreign Mission School

The Foreign Mission School was an educational institution which existed between 1817 and 1826 in Cornwall, Connecticut. It was established by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to bring Christianity and Western culture to non-White people by educating missionaries of their own culture.

Steward's House-Foreign Mission School | |

The Steward's House of the Foreign Mission School | |

| |

| Location | 14 Bolton Hill Rd., Cornwall, Connecticut |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°50′40″N 73°19′57″W |

| Area | 3 acres (1.2 ha) |

| Built | 1817 |

| Architectural style | Federal |

| NRHP reference No. | 16000858[1] |

| Added to NRHP | October 31, 2016 |

History

The school was called a seminary at the time, "for the purpose of educating youths of Heathen nations, with a view to their being useful in their respective countries" according to Jedidiah Morse.[2] The school was established in the last few months of 1816, and opened in May 1817. The first principal was Edwin Welles Dwight (1789–1841). After the first year, Dwight was replaced by Reverend Herman Daggett who ran the school for the next six years.[3]

Daggett was nephew of Naphtali Daggett who had been president of Yale College, and Dwight was distant cousin of the Yale president in 1817, Timothy Dwight IV.[4] Approximately one hundred young men from non-European indigenous peoples were trained at the school with the intent of their becoming missionaries, preachers, translators, teachers, and health workers in their native communities. [5]

According to Morse,

there belong to it (the school) a commodious edifice for the School, a good mansion house, with a barn, and other out-buildings, and a garden for the Principal; a house, barn, &. with a few acres of good tillage land for the Steward and Commons; all situated sufficiently near to each other; and eighty acres of excellent wood land, about a mile and a half distant.

In the constitution there is a provision, that youths of our own country, of acknowledged piety, may be admitted to the school, at their own expense, and at the discretion of the Agents.

Under the instruction of the able and highly respected Principal, the Rev. Mr. Daggett, and his very capable and faithful assistant, Mr. Prentice, the improvement of the pupils, in general, has been increasing and satisfactory, and in not a few instances, uncommonly good. Besides being taught in various branches of learning, and made practically acquainted with the useful arts of civilized life; they are instructed constantly, and with special care in the doctrines and duties of Christianity. Nor has this instruction been communicated in vain. Of the thirty-one Heathen youths . . . seventeen are thought to have given evidence of a living faith in the Gospel; and several others are very seriously thoughtful on religious concerns.[6]

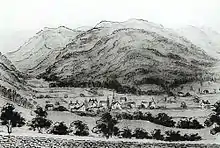

From its founding, the school rapidly became a symbol of American Christianity's Second Great Awakening, and connected the small farm town of Cornwall in Connecticut's Litchfield Hills to the early 19th century's clash of civilizations, as epitomized by the Trail of Tears, the conversion of Hawaii to Protestantism, and the worldwide Christian missionary movement. Cornwall had been chosen for the school's location due to the devoutness of the residents and their consequent willingness to donate their efforts, money, and property to a devout cause, as well as their reputation as hard-working people of good character.[6]

Henry Opukahaia, the school's first pupil, was an 18-year-old Native Hawaiian abandoned in New Haven, Connecticut in 1810 by his ship. He traveled widely to promote the school, but died in Cornwall in 1818 at 26 before he could return home. He recruited four more Hawaiians, including one who called himself "George Prince" with a record of fighting in the War of 1812, and the school printed a pamphlet with their stories to raise money.[7] Samuel F. B. Morse, son of Jedidiah, painted their portraits. Other students came from distant countries as well as many Native American tribes,[6] bringing 24 different native languages.[5]

In its first year, the school had twelve students; seven Hawaiians, one Hindu, one Bengali, a Native American, and two Anglo-Americans. By the second year, there were twenty-four; four Cherokee, two Choctaw, one Abenaki, two Chinese, two Malays, one Bengali, one Hindu, six Hawaiians, and two Marquesans, as well as three Anglo-Americans.[6]

The students followed a demanding schedule befitting the devout mission of the school, doing field work in the time unoccupied by their mandatory church attendance, prayer, and 7 hours of daily coursework. The program of study included astronomy, calculus, theology, geography, chemistry, navigation and surveying, French, Greek, and Latin, in addition to practical courses such as blacksmithing and coopering.[5]

In time, as the pendulum of public opinion began to build doubt about the purpose of the school, support began to wane; it never came to a head, however, before the marriages of two Cherokee students to local girls and the potential marriages of other such couples caused negative reactions among both the local residents and the members of the Native American tribes who sent their sons there, and it was closed in 1826 or 1827.[5]

Native American students

Principal Daggett observed in a letter to Morse that, in contrast to the Native American students, three of the students from the Pacific Islands had become ill and "fallen a sacrifice", which he assigned to the climate; he mused that "it is probable, that Divine Providence intends this school to be chiefly useful to the Aborigines of this country." And in fact, sons of some of the most prominent Native American leaders of the time (many of mixed ancestry) received their education at the Foreign Mission School, later becoming distinguished members of their nations. Three Cherokees and a Choctaw came to the school in the fall of 1818. In his report, Morse stated that there were twenty-nine students in the school in 1820, half of whom were Native American boys from the principal families of five or six different tribes.[6] Some of the Native American students include:[6]

- David Brown, a Cherokee (one quarter white on his father's side) came from a prominent family, his half brother being a chief and judge. He assisted in developing a spelling book for the Cherokees as well as a Cherokee grammar. After leaving the school, he became a notable public speaker, studied Hebrew and divinity, and, after attending Andover became a prominent member of the Cherokee nation and served as clerk of a delegation to Congress.

- James Fields, another Cherokee and a kinsman of Brown, did not distinguish himself academically, but spent his life "taking care of his considerable property."

- Leonard Hicks was a son of Chief Charles Renatus Hicks, the first Cherokee convert to Christianity, and considered the most influential man in his nation. After he became homesick and left the school, Leonard served as clerk of the Cherokee nation.

- Tah-wah (renamed David Carter) was a grandson of Nathaniel Carter of Killingworth and Cornwall; his father (also named Nathaniel Carter) was taken as a child after his parents were killed during the Wyoming Valley massacre in Pennsylvania c.1763. His sisters were ransomed back to family in CT, but Nathaniel remained with the tribe for the rest of his life, marrying a Cherokee woman. David was dismissed from the school for reasons related to the scandal of Cherokee men marrying white women (see Boudinot & Gold and Ridge & Northrup); he attained prominence, however, became editor of the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper and a judge of the Supreme Court. He lived for a time in Goshen, Connecticut, apparently with his aunt. He died about 1863.

- John Vann, the son of a white man, Clement Vann and his Native American wife Mary Christiana who converted to Christianity, attended the school from 1820 to 1822. He became editor of the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper.

- McKee Folsom and Israel Folsom, the sons of a white man, Nathaniel Folsom, were the first Choctaws listed as attending the school, from 1818 to 1822. Their family was very prominent in the nation, and they assisted in arranging a Choctaw alphabet, preparing Choctaw school books, and translating the Scriptures to Choctaw.

- Adin C. Gibbs, a Delaware (part white) from Pennsylvania, attended the school from 1818 to 1822. He later spent many years among the Choctaw as a teacher and missionary.

- Holbochinto (renamed Robert Monroe), was a relative of Tally, Chief of the Osage Nation. He attended the school from 1824 to 1826, supported by the Foreign Mission Society.

- Wah-che-oh-heh, (renamed Stephen Van Rensselaer after General Stephen Van Rensselaer III, who was also president of the United Foreign Mission Society which supported him) was also a relative of Tally; he attended the school from 1824 to 1825. He remained at Cornwall after the school closed, later attending Miami University. In 1832 he was one of five from the school to act as missionary helper. Afterwards, he served his tribe as a blacksmith and interpreter.

- John Ridge, son of Major Ridge, commander of the Cherokees in the Seminole War, was a student at the school in 1819. Suffering from a problem with his hip, he was nursed for two years in the home of John P. Northrup, steward of the school; this led to his marriage to Sarah Bird Northrup in 1824, which was not well received by the local citizens. Ridge subsequently went on to become a prominent leader of the Cherokee nation.

- Kul-le-ga-nah (renamed Buck Watie, then renamed Elias Boudinot after Elias Boudinot who sponsored him at the school in 1818) calculated the date of the lunar eclipse of August 2, 1822, using only the information supplied in his textbook. He became engaged to marry Cornwall local Harriet R. Gold in 1825. This was bitterly opposed by the bride's family and the citizens of Cromwell, who burned the couple in effigy. They went on to get married nevertheless.

- Miles Mackey, a Choctaw (half white) who attended the school from 1823 to 1825, was dismissed "for a proposed matrimonial union", as was James Terrell an Osage.

The response to these marriages was negative among both the citizens of Cornwall and those of the Native American nations; in addition, some of the southern tribes became concerned that residence in the northern states was harming the health of the students sent there, and support for the school rapidly dwindled, until it was closed in 1826 or 1827.[6]

The school was dramatized in an episode of the American Experience television series in 2009.[8]

In 2014 Alfred A. Knopf published The Heathen School: A Story of Hope and Betrayal in the Age of the Early Republic, a historical narrative with modern perspectives and reporting by Yale historian John Demos.[9] The Steward's House, the only relatively unaltered remnant of the school's historic Cornwall campus, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2016 in recognition of the school's significance.[10]

See also

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Jedidiah Morse (1822). A report to the Secretary of War of the United States, on Indian affairs. S. Converse. pp. 163, 264–266.

- William Buell Sprague; Timothy Stone (1859). "Herman Daggett". Annals of the American Pulpit: Trinitarian Congregational. 2. Robert Carter and brothers. pp. 291–756.

- Benjamin Woodbridge Dwight (1874). The history of the descendants of John Dwight, of Dedham, Mass. 2. J. F. Trow & son, printers and bookbinders. pp. 754–756.

- "The Foreign Mission School, 1817-1826 Archived 2009-06-30 at the Wayback Machine", Cornwall Historical Society

- Carolyn Thomas Foreman (September 1929). "The Foreign Mission School at Cornwall, Connecticut". Chronicles of Oklahoma. Oklahoma Historical Society. 7 (3): 242–259.

- Douglas Warne (2002). "George Prince Kaumualiʻi, the Forgotten Prince". Hawaiian Journal of History. 36. Hawaiian Historical Society. pp. 59–71. hdl:10524/203.

- "We Shall Remain: The Trail of Tears". The American Experience. WGBH-TV. April 27, 2009. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- What US Learned from Heathen School Wasn't Part of the Lesson Plan, Maureen Corrigan's review of The Heathen School by John Demos, NPR.org, March 18, 2014

- "NHL nomination for Steward's House, Foreign Mission School" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2017-03-12.

External links

- Educating the Heathen , John Andrew, Cornwall Historical Society, 1978