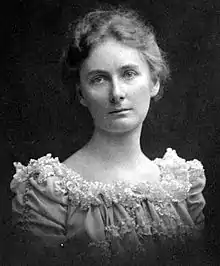

Florence Bascom

Florence Bascom (July 14, 1862 – June 18, 1945) was the second woman to earn her PhD in geology in the United States, and the first woman to receive a PhD from Johns Hopkins University, which occurred in 1893.[1][2] She also became the first woman to work for the United States Geological Survey, in 1896.[3][4] As well as being one of the first women to earn a master's degree in geology, she was known for her innovative findings in this field, and led the next generation of female geologists. Geologists consider her to be the "first woman geologist in this country America."[4]

| Florence Bascom | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 14, 1862 Williamstown |

| Died | June 18, 1945 (aged 82) Williamstown |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation | |

| Employer | |

| Parent(s) | |

"The fascination of any search after truth lies not in the attainment, which at best is found to be very relative, but in the pursuit, where all the powers of the mind and character are brought into play and are absorbed by the task. One feels oneself in contact with something that is infinite and one finds joy that is beyond expression in sounding the abyss of science and the secrets of the infinite mind." - Florence Bascom[4]

Early life

Florence Bascom was born in Williamstown, Massachusetts on July 14, 1862.[5] The youngest of five children, Bascom came from a family who, unlike most at the time, encouraged women's entrance into society.[2] Her father, John Bascom, was a professor at Williams College, and later President of the University of Wisconsin.[6] He was the driving factor of her career and her first contact in the field of Geology.[2] Her mother, Emma Curtiss Bascom, was a women's rights activist involved in the suffrage movement.[2] Her parents were steadfast supporters of women's rights and encouraged women to obtain a college education.

Her father, John Bascom became the president of the University of Wisconsin in 1874. Just one year later in 1875, the university began accepting women. Bascom Hill within the Madison campus was named after the family and their legacy.[4]

She was born at a time when Civil War was splitting the country. She grew up in a household where her family emphasized the importance of gender equality. Her father commemorated women and their importance in society. She had a very high maturity level from a very young age and was very close to her father. Her father had struggled with mental illness and used his children as a way to help him overcome it. He did so by bringing his children to the mountains and did this to promote natural science. Florence graduated with high grades from Madison High School at the age of 16.[7]

Education

She earned a bachelor's degree in arts and letters in 1882,[4] and a Bachelor of Science in 1884 from the University of Wisconsin.[8] After persuasion from her father and a rejection from another school, Bascom obtained her first science degree, which turned her interest towards geology.[9] In 1887 she obtained her Master of Science degree from the same university. During this time women had limited access to educational resources, such as the library and gymnasium, but also limited access to classrooms if men were already in them. Her professors at the University of Wisconsin, Roland Duer Irving and Charles R. Van Hise, were part of the USGS.[10] Bascom received her PhD at Johns Hopkins University. While studying at Johns Hopkins she was forced to sit behind a screen so as not to disturb the men in the class, whose education was the priority.[6] Since Geology at the time was purely a male discipline, Bascom faced many challenges getting her education and establishing herself in her field; this led to her becoming known as the "Pioneer of Women Geologists."[2]

She was the second woman to obtain a Ph.D. in Geology. She was the first female geologist to present a paper before the Geological Survey of Washington, in 1901.[11] She was also the first woman elected to the Council of the Geological Society of America (in 1924; no other woman was elected for more than two decades).[11] She was the first female officer of the Geological Society of America, and in 1930 became the second Vice-President.[2]

After receiving her B.A in 1884, she started her college teaching career at the Hampton School of Negroes and American Indians (currently known as Hampton University), working there for a year before going back to University of Wisconsin for her master's .

While attending the University of Wisconsin Florence Bascom was a member of the Kappa Kappa Gamma chapter. Bascom was one of the first members to join an all women's fraternities between 1867 and 1902.[12]

Work

Florence Bascom contributed to a special type of identification for acidic volcanoes. Her journal, The Structures, Origin, and Nomenclature of Acidic Volcanic Rocks of South Mountain, begins by identifying various rock structures formed by the volcano. Bascom argues that South Mountain's rock formations have changed over time, with some rocks originally showing signs of being rhyolite, but now holocrystalline rock. These rocks defy the nomenclature used to identify rocks invented by German and English scientists, so she created prefixes to add to these pre-existing names, to identify acidic changes in rocks. The prefixes she came up with are meta, epi, and apo.[13]

Florence presented a second notable new conclusion regarding the cycles of erosion within Pennsylvania; earlier scientific thought was that the Piedmont province of Pennsylvania was made by two to three erosion cycles, while she had evidence there were at least nine cycles. Florence found this by compiling a stratigraphic record of Atlantic deposit in the province, listing the depth, unconformities, and different grain sizes (like sand, clay, or gravel). The cycles occurred over a large period of time, with six cycles occurring in the post-Cretaceous period and three occurring in the Cretaceous period. This conclusion gave scientists new ideas about erosion cycles regarding their rate of occurrence and how to define a cycle. [14] In 1896 Bascom worked as an assistant for the (USGS). Her role in the team was to study crystalline schists in a square degree of area along eastern Pennsylvania and Maryland, as well as a portion of northwest Delaware. For part of her life as a teacher, she simultaneously worked in the geological survey. Her work lead to a multitude of comprehensive reports of geologic folios.[15]

She also held a career as a teacher. She taught mathematics and science at Rockford College from 1887 to 1889, and later at Ohio State University from 1893 to 1895.[16] She left Ohio State University to work at Bryn Mawr College where she could conduct original research and teach higher-level geology courses. Bascom even took a leave from her teachings in 1907 due to her interest to study petrography and mineralogy. She spent a year learning and researching advanced crystallography in the laboratory of Victor Goldschmidt and Heidelberg before going back to teaching as she did not want to spend time doing “overspecialistic research,” that she would not be able to teach to her students in the courses offered.[15]

At Bryn Mawr College, geology was considered adjunct in comparison to other natural sciences. Her workspace consisted of storage space in a building constructed solely for chemistry and biology. Over two years she managed to develop a substantial collection of minerals, fossils, and rocks. Bascom founded Bryn Mawr's department of Geology in 1901. She proceeded to teach and train a generation of young women in this department. In 1937, 8 out of 11 of the women who were Fellows of the Geological Society of America were graduates of Bascom's course at Bryn Mawr College. In the first third of the 20th century, Bascom's graduate program was considered to be one of the most rigorous in the country, with a strong focus on both lab and fieldwork. It was known for training the most American female geologists. Her students did not just graduate, they often succeeded in important geology careers for themselves. Bascom took a leave from her teachings in 1907 due to her interest to study petrography and mineralogy. Many got positions in government as University teachers, as well as federal and in-state surveyors. Additionally during WW2 some of her students were involved in confidential work for the Military Geology Unit in the U.S. Geological Survey.[15]

She was known to set high standards for her students as well as herself. Though she was extremely tough on her students, they were grateful for the quality of education that she gave to them.[2]

Bascom retired from teaching in 1928 but continued to work at the United States Geological Survey until 1936.[6]

Notable mentors

Her father, John Bascom, played a pivotal role in Florence Bascom becoming a geologist, beginning when Florence was 12 and her father moved her and her family from their hometown to accept the position as President of the University of Wisconsin, the university where Bascom would begin her education. Her interest in geology began with her father; she believed "they understood each other" and stated he was "All that [she] needed, association with him gratified all [she] wanted or needed so far as men were concerned." The above quote references the network of male coworkers a woman would have to gain to be respected in a scientific field. It was a drive with her father who pointed out a landscape that she did not understand, that intrigued her enough to learn about the earth and geologic processes.[2]

Bascom trained under experts in metamorphism and crystallography.[4] Bascom's choice of study was strongly influenced by Roland Duer Irving, a professor at the University of Wisconsin, and Charles R. Van Hise, who was Irving's assistant. In the years she worked under these two, 1884–1887, the Geological Survey in Washington had established a division of glacial geology, motivating her to enter the field of petrography and structural geology. This led Bascom to analyze formations in South Mountain in Maryland. These formations were regarded as sediments but under close observation Bascom arrived at the conclusion that the formations were altered volcanic, which she identified as, "Apor-hyolites". Being an expertise in mineralogy, petrology, and crystallography[16] she used these ideas to create her masters thesis which was finalized and named, "The Sheet Gabbros of Lake Superior."[17]

George Huntington Williams (1856–94): Bascom met George Huntington Williams through her early mentor Irving and later worked with Williams in field research while she was at Johns Hopkins. Bascom began her studies at Hopkins and was told there was a chance she would not get her degree because she was a woman. Williams supported her and she later received her PhD.[2]

Edward Francis Baxter Orton (1829–99): Bascom worked with Edward Francis Baxter Orton while she was at Ohio State University.[2]

Victor Mordechai Goldschmidt (1853–1933): Bascom studied crystallography under Victor Mordechai Goldschmidt while on leave in Germany in 1906 – 1907.[2]

Legacy

Florence Bascom left a legacy in part due to her significant scientific discoveries, but also partly due to her legacy of training a number of future women geologists. Bascom founded the geology department at Bryn Mawr College and encouraged other women to enter the field of geology.[2] Bascom trained and mentored Louise Kingsley, Katherine Fowler Billings, petrologist Anna Jonas Stose, petrologist Eleanora Bliss Knopf, crystallographer Mary Porter, paleontologist Julia Gardner, petroleum geologist Maria Stadnichenko, glacial geomorphologist Ida Ogilvie, Isabel Fothergill Smith, Dorothy Wyckoff, and Anna Heitonen.[4]

Bascom's students went on to be successful scientists and some were featured in American Men of Science. Those featured were Ida Ogilvie, Eleanor Bliss (Knopf), Anna Jonas (Stose), Isabel Smith, and Julia Gardner.[2]

Death

Bascom died of a stroke (cerebral hemorrhage) on June 18, 1945, at the age of 82.[16] She is buried in a Williams College cemetery in Williamstown, close to family members.[18]

Named in honor of Florence Bascom

- Bascom Crater on Venus

- 6084 Bascom, an asteroid discovered in 1985

- Glacial Lake Bascom, a prehistoric, postglacial lake located in what is now northern Berkshire County, Massachusetts, formed when receding glacial ice acted as a dam and prevented drainage of the Hoosic River watershed.

- The U.S. Geological Survey's Florence Bascom Geoscience Center located in Reston, Virginia

Publications

| Library resources about Florence Bascom |

| By Florence Bascom |

|---|

Florence Bascom published over 40 articles on genetic petrography, geomorphology (specifically the provenance of surficial deposits),[4] and gravel.[5] Her own account of her youth in Madison may be found in the Wisconsin Magazine of History with the title "The University in 1874–1887", March 1925.[19]

- "John Bascom's Signature" The Wisconsin Magazine of History, June 1925[20]

- "The Geology of the Crystalline Rocks of Cecil County" Maryland Geological Survey (1902)

- "The ancient volcanic rocks of South Mountain, Pennsylvania" Pennsylvania US Geological Survey Bulletin No. 136 (1896)

- "Water resources of the Philadelphia district" US Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper No. 106 (1904)

- "Geology and mineral resources of the Quakertown-Doylestown district, Pennsylvania and New Jersey" Edgar Theodore Wherry and George Willis Stose. US Geological Survey Bulletin No. 828 (1931)

- "Elkton-Wilmington folio, Maryland-Delaware-New Jersey-Pennsylvania" with B.L. Miller. Geologic atlas of the United States; Folio No. 211 (1920)

- American Mineralogist, Volume 31, 1946

- Bryn Mawr Alumnae Bulletin, November, 1945; spring, 1965

- Science, September, 1945

- University of Wisconsin Department of Geology and Geophysics Alumni Newsletter, 1991

- Arnold, Lois Barber, Four Lives in Sciences, Schocken Books, 1984

- Smith, Isabel F., The Stone Lady: A Memoir of Florence Bascom, Bryn Mawr College, 1981[21]

See also

References

- "Florence Bascom papers, 1883-1938". Dla.library.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2018-07-28.

- Clary, R. M.; Wandersee, J. H. (2007-01-01). "Great expectations: Florence Bascom (1842–1945) and the education of early US women geologists". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 281 (1): 123–135. Bibcode:2007GSLSP.281..123C. doi:10.1144/SP281.8. ISSN 0305-8719. S2CID 128838892.

- "The Stone Lady, Florence Bascom (U.S. National Park Service)". Nps.gov. 1945-06-18. Retrieved 2018-07-28.

- Schneidermann, Jill (July 1997). "A Life of Firsts: Florence Bascom" (PDF). GSA Today. Geological Society of America. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- "Florence Bascom | American educator and scientist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-08-11.

- Gohn, Kathleen K. (2004). "Celebrating 125 Years of the U.S. Geological Survey" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1274. p. 4. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- "Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia". 2002.

- Oakes, Elizabeth H. (2007). Encyclopedia of world scientists (Rev. ed.). New York: Facts on File. p. 47. ISBN 9781438118826. OCLC 466364697.

- Rosenberg, Carroll S. (1971). James, Edward T.; Boyer, Paul S.; James, Janet Wilson (eds.). Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary. 1. Harvard University Press. pp. 108–110. ISBN 9780674627345.

- "Florence Bascom, Pioneer Geologist | Science Features". www2.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-11-03. Retrieved 2016-11-01.

- irishawg (2016-08-20). "Women in Geoscience Series – Irish Association for Women in Geosciences". Irishawg.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2018-07-28.

- Becque, Frances DeSimone (2002). "C O ED UC A TIO N A N D THE HISTORY OF W OM EN'S FRATERNITIES". ProQuest 275858820. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Bascom, Florence (1893). "The Structures, Origin, and Nomenclature of the Acid Volcanic Rocks of South Mountain". The Journal of Geology. 1 (8): 813–832. Bibcode:1893JG......1..813B. doi:10.1086/606233. S2CID 129514458.

- Bascom, Florence (1921). "Cycles of Erosion in the Piedmont Province of Pennsylvania". The Journal of Geology. 29 (6): 540–559. Bibcode:1921JG.....29..540B. doi:10.1086/622809. JSTOR 30063181.

- Knopf, Eleanora Frances Bliss (1946). "MEMORIAL OF FLORENCE BASCOM" (PDF).

- Gates, Alexander E. (2009). A to Z of Earth Scientists. Facts on File. ISBN 9781438109190.

- James, Edward T. (1971). Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary. Radcliffe College: Harvard University Press. p. 108. ISBN 9780674627345. Retrieved 11 October 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- "Florence Bascom facts". biography.yourdictionary.com/Florencebascom.

- Bascom, Florence (1924–1925). "The University in 1874–1887". The Wisconsin Magazine of History. Wisconsin Historical Society. pp. 300–308. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- Bascom, Florence (1925). "John Bascom's Signature". The Wisconsin Magazine of History. 8 (4): 460. JSTOR 4630573.

- "Florence Bascom Facts". biography.yourdictionary.com. Retrieved 2016-10-06.

Further reading

- Reynolds, Moira Davidson (2004). American women scientists: 23 inspiring biographies, 1900-2000. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 9780786421619.

- Wayne, Tiffany K. (2011). American women of science since 1900. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598841596.

- Ignotofsky, Rachel (2016). Women in science : 50 fearless pioneers who changed the world. Ten Speed Press. ISBN 9781607749769.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Florence Bascom. |

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070218210740/http://library.thinkquest.org/20117/bascom.html

- Geological Society of America article mentioning the Wissahickon controversy

- Florence Bascom at Find a Grave

- Florence Bascom papers at the Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Special Collections.

- TrowelBlazers entry for Florence Bascom.