Floor plate

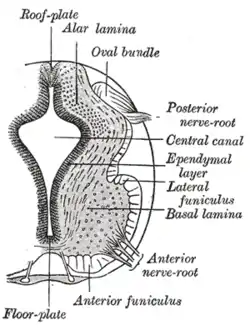

The floor plate is a structure integral to the developing nervous system of vertebrate organisms. Located on the ventral midline of the embryonic neural tube, the floor plate is a specialized glial structure that spans the anteroposterior axis from the midbrain to the tail regions. It has been shown that the floor plate is conserved among vertebrates, such as zebrafish and mice, with homologous structures in invertebrates such as the fruit fly Drosophila and the nematode C. elegans. Functionally, the structure serves as an organizer to ventralize tissues in the embryo as well as to guide neuronal positioning and differentiation along the dorsoventral axis of the neural tube.[1][2][3]

| Floor plate | |

|---|---|

The floor plate separates the left and right basal plates of the developing neural tube. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Notochord |

| System | Nervous system |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Induction

Induction of the floor plate during embryogenesis of vertebrate embryos has been studied extensively in chick and zebrafish and occurs as a result of a complex signaling network among tissues, the details of which have yet to be fully refined. Currently there are several competing lines of thought. First, floor plate differentiation may be mediated by inductive signaling from the underlying notochord, an axial mesoderm derived signaling structure. This is supported experimentally in chick, in which floor plate induction, as well as associative ventral nervous tissue differentiation, is mediated by the secreted signaling molecule sonic hedgehog (Shh). Shh is expressed in a gradient with highest concentration localized in the notochord and floor plate. In vitro tissue grafting experiments show that removal of this molecule prevents differentiation of the floor plate, whereas its ectopic expression induces differentiation of floor plate cells.[4] An alternative view proposes that neural tube floor plate cells stem from precursor cells which migrate directly from axial mesoderm. Through chick – quail hybrid experiments as well as genetic interaction experiments in zebrafish, it appears that notochord and floor plate cells originate from a common precursor. Furthermore, in zebrafish, Nodal signaling is required for differentiation of medial floor plate cells whereas Shh is expendable. These data may indicate that the floor plate induction mechanism in amniotes and anamniotes differs.[5] To reconcile these differences, a dual-mode induction model has been proposed in chick. In this model, exclusively ectodermal cells are induced to become medial floor plate during gastrulation by prechordal mesoderm, possibly through Nodal signaling. Later in development during neurulation, extended contact and interaction between notochord and fated floor plate cells causes differentiation, suggesting a cooperative effect between Nodal and Shh signaling.[6]

Axon guidance

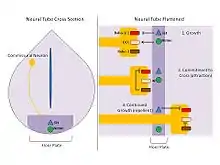

In the development of the central nervous system, the decision of a neuron to cross or not cross the midline is critical. In vertebrates, this choice is mediated by the floor plate, and enables the embryo to develop successful left and right body halves with respect to nervous tissue. For example, while ipsilateral neurons do not cross the midline, commissural neurons cross the midline forming a single commissure. These particular neurons develop in the dorsal region of the neural tube and travel ventrally toward the floor plate. Upon reaching the floor plate, commissural neurons cross through the structure to emerge on the opposite side of the neural tube, whereupon they project anteriorly or posteriorly within the tube.[7]

- Netrins: Netrins are proteins expressed and secreted by cells of the floor plate. Experiments using floor plate extracts and commissural neurons embedded in a collegen matrix show attraction of neurons towards the floor plate in vitro.[8] Moreover, Isolation and transfection of Netrin-1 and Netrin-2, two secreted proteins, into Cos cells has similar effects.[9] Further research confirmed that Netrins act as attractant proteins in addition to Shh to guide commissural axons toward the floor plate.[10] Netrins are secreted by the floor plate cells and function to bind the axon receptor DCC in a chemotactic manner.

- Slit: Slit is a secreted ligand expressed in the floor plate and functions to inhibit axonal crossing of the neural tube. While netrins attract commissural neurons toward the midline, slit proteins repel and expel neurons from the midline. As axons not destined to cross the midline project through the neural tube they are repelled by the ligand slit which is expressed in the cells of the floor plate. Slit acts through its receptors Roundabout (Robo) 1 and 2. This interaction inhibits the chemotaxis provided by the Netrin/DCC pathway. However, Robo-3 (Rig-1) is upregulated during growth of commissural axons during migration toward the floor plate, which sequesters Robo-1/2 inside the cell within vesicles. Consequently, the Netrin/DCC attraction pathway dominates over the Slit/Robo repulsion pathway and the axon can grow toward the midline and enter the floor plate. Upon entering, through a mechanism not yet fully understood, Robo-3 becomes downregulated and this liberates and upregulates Robo-1/2, effectively repelling the neuron from the floor plate midline. Through this complex cross talk of Slit, Robo-1/2, and Robo-3, commissural axons are guided toward the midline to cross the neural tube and prevented from crossing back.[11]

The signaling molecules guiding the growth and projections of commissural neurons have well studied homologs in invertebrates. In the Netrin/DCC chemoattraction pathway the C. elegans homologs are Unc-6/Unc-40 and Unc-5 while the Drosophila homologs are Netrin-A and Netrin-B/Frazzled and Dunc5. In the Slit/Robo chemoreppelant pathway the C. elegans homologs are Slt-1/Sax-3 whereas the Drosophila homologs are also known as Slit/Robo(1-3).[7]

Glial fate mapping

In the central nervous system (CNS), overall cell fate mapping is typically directed by the sonic hedgehog (Shh) morphogen signaling pathway. In the spinal cord, Shh is directed by both the notochord and floor plate regions which ultimately drives the organization of neural and glial progenitor populations. The specific glial populations impacted by Shh in these two regions include oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), oligodendrocytes, NG2+ cells, microglia, and astrocytes.[12] The floor plate (FP) region of the spinal cord individually contributes to gliogenesis, or the formation of glial cells. Traditionally, progenitor cells are driven from their progenitor expansion phase, to the neurogenic phase, and ultimately to the gliogenic phase. From the gliogenic phase, the former progenitor cells can then become astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, or other more specialized glial cell types. Recently, there have been efforts to use conditional mutagenesis to selectively inactivate the Shh pathway specifically in the FP region to identify different roles of molecules involved in oligodendrocyte cell fate. Oligodendrocytes are the cells responsible for myelinating axons in the CNS.

Shh regulates Gli processing through two proteins, Ptch1 and Smo.[13] When Shh is not active, Ptch1 is responsible for suppressing the pathway through the inhibition of Smo. Smo is crucial to the overall transduction of signal of the Shh pathway. If Smo is inhibited, the Shh pathway is also inactive, which ultimately represses gliogenesis. Specific factors such as Gli3 are required for oligodendrocyte cell fate. Since Shh regulates Gli processing, if Smo is compromised or inhibited by Ptch1, this inactivates the Shh pathway and prevents Gli processing which disrupts glial cell fate mapping. Shh signaling in the FP region is very important because it needs to be active in order for gliogenesis to occur. If Shh is inactivated within the FP region and activated in other regions of the spinal cord such as the Dbx or pMN domains, gliogenesis is compromised. But, when Shh is active in the FP region, gliogenesis is activated and glial cells begin migrating to their targeted destinations to function.

Spinal cord injury and axon regeneration

The floor plate region aids in axon guidance, glial fate mapping, and embryogenesis. If this area of the spinal cord becomes injured, there could be serious complications to all contributing functions of this region, namely limited proliferation and production of the glial cells responsible for myelination and phagocytosis in the CNS. Spinal cord injury (SCI) also most often results in axon denudation or severance. Wnt signaling is a common signaling pathway involved in injury cases. Wnt signaling regulates regeneration after spinal cord injury. Immediately following injury, Wnt expression dramatically increases.[14] Axon guidance is driven by Netrin-1[8] in the FP region of the spinal cord. During injury cases, specifically cases of axon severance, Wnt signaling is upregulated and axons begin to initiate regeneration and the axons are reguided through the FP regions using Shh and Wnt signaling pathways.

The spinal cord ependymal cells also reside in the FP region of the spinal cord. These cells are a neural stem cell population responsible for repopulating lost cells during injury. These cells have the capacity to differentiate into progenitor glial populations. During injury, a factor entitled Akhirin is secreted in the FP region. During spinal cord development, Akhirin is expressed solely on ependymal stem cells with latent stem cell properties and plays a key role in the development of the spinal cord. In the absence of Akhirin, stemness of these ependymal cells is not regulated.[15] Injury compromises Akhirin expression and regulation and the cells of the FP region cannot properly be restored by the ependymal stem cell populations.

References

- "Wolpert, Lewis. Principles of Development: 3rd Edition. Oxford University Press, 2007."

- "Gilbert, Scott F. Principles of Development: 8th Edition. Sinauer Associates, Inc. 2006."

- "Jessell, Thomas M. Neuronal Specification in the spinal cord: inductive signals and transcriptional codes. Nature Reviews Genetics. Oct, 2000(1)"

- "Yamada, T. Control of Cell Pattern in the Developing Nervous System: Polarizing Activity of the Floor Plate and Notochord. Cell, Vol. 64, 635-647, February 8, 1991"

- "Strahle, Uwe, et al. Vertebrate floor-plate specification: variations on common themes. Trends in Genetics Vol.20 No.3 March 2004"

- "Patten, Iain, et al. Distinct modes of floor plate induction in the chick embryo. 19 June 2003. Development 130, 4809-4821"

- "Guan KL and Rao Y. Signalling mechanisms mediating neuronal responses to guidance cues. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003 Dec;4(12):941-56."

- "Serafini, Tito, et al. The Netrins Define a Family of Axon Outgrowth-Promoting Proteins Homologous to C. elegans UNC-6. Cell, Vol. 79, 409-424. August 12, 1994"

- "Kennedy, Timothy E, et al. Netrins Are Diffusible Chemotropic Factors for Commissural Axons in the Embryonic Spinal Cord. Cell, Vol. 79, 425-435, August 12, 1994"

- "Charron, F, et al. The morphogen sonic hedgehog is an axonal chemoattractant that collaborates with netrin-1 in midline axon guidance. Cell. 2003 Apr 4;113(1):11-23."

- "Long, Hua et al. Conserved Roles for Slit and Robo Proteins in Midline Commissural Axon Guidance. Neuron, Vol. 42, 213–223, April 22, 2004"

- Yu, Kwanha; McGlynn, Sean; Matise, Michael P. (2013-04-01). "Floor plate-derived sonic hedgehog regulates glial and ependymal cell fates in the developing spinal cord". Development. 140 (7): 1594–1604. doi:10.1242/dev.090845. ISSN 0950-1991. PMC 3596997. PMID 23482494.

- Bai, C. Brian; Auerbach, Wojtek; Lee, Joon S.; Stephen, Daniel; Joyner, Alexandra L. (October 2002). "Gli2, but not Gli1, is required for initial Shh signaling and ectopic activation of the Shh pathway". Development. 129 (20): 4753–4761. ISSN 0950-1991. PMID 12361967.

- Zou, Yimin (2015). "Wnt Signaling in Spinal Cord Injury". Wnt Signaling in Spinal Cord Injury - Neural Regeneration - Chapter 15. pp. 237–244. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801732-6.00015-X. ISBN 9780128017326.

- Abdulhaleem M, Felemban Athary; Song, Xiaohong; Kawano, Rie; Uezono, Naohiro; Ito, Ayako; Ahmed, Giasuddin; Hossain, Mahmud; Nakashima, Kinichi; Tanaka, Hideaki (2015-05-01). "Akhirin regulates the proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells in intact and injured mouse spinal cord". Developmental Neurobiology. 75 (5): 494–504. doi:10.1002/dneu.22238. ISSN 1932-846X. PMID 25331329.