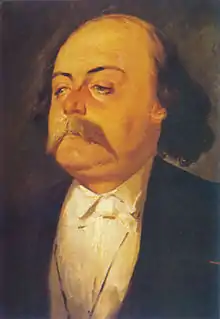

Flaubert's letters

The letters of Gustave Flaubert (French: la correspondance de Flaubert), the 19th-century French novelist, range in date from 1829, when he was 7 or 8 years old, to a day or two before his death in 1880.[1] They are considered one of the finest bodies of letters in French literature, admired even by many who are critical of Flaubert's novels.[2] His main correspondents include family members, business associates and fellow-writers such as Théophile Gautier, the Goncourt brothers, Guy de Maupassant, Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve, George Sand, Ivan Turgenev and Émile Zola. They provide a valuable glimpse of his methods of work and his literary philosophy, as well as documenting his social life, political opinions, and increasing disgust with bourgeois society.

Correspondents

4481 letters by Flaubert survive,[3] a number which would have been considerably higher but for a series of burnings of his letters to his friends. Many of those addressed to Maxime Du Camp, Guy de Maupassant and Louis Bouilhet were destroyed in this way.[4] From those that survive it appears that his principal correspondents were as follows.[5] His family members:

- Anne Justine Caroline Flaubert, his mother

- Caroline Hamard, his sister

- Caroline Commanvile, his niece

- Ernest Commanville, his niece's husband

His friends, associates and readers:

- Agénor Bardoux, politician

- Princesse Mathilde Bonaparte, niece of Napoleon I, cousin of Napoleon III, literary patron

- Amélie Bosquet (FR), feminist writer

- Louis Bouilhet, poet and friend of Flaubert from childhood

- Marie-Louise Léonie Brainne (née Rivière), journalist

- Maxime Du Camp, journalist, photographer and travelling companion of Flaubert

- Marie-Sophie Leroyer de Chantepie (FR), minor novelist

- Georges Charpentier, publisher

- Ernest Chevalier (FR), judge and friend from childhood

- Louise Colet, poet and Flaubert's lover

- Jules Duplan, businessman

- Ernest-Aimé Feydeau, writer

- Frédéric Fovard, notary

- Théophile Gautier, poet and writer

- Edma Roger des Genettes, literary and artistic salonnière

- Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, novelists and diarists

- Edmond Laporte, local politician and businessman

- Alphonse Lemerre, publisher

- Philippe Leparfait, adopted son of Louis Bouilhet

- Michel Lévy, publisher

- Guy de Maupassant, short-story writer

- Claudius Popelin (FR), painter, writer and sometime lover of Princesse Mathilde Bonaparte

- Edgar Raoul-Duval, politician

- Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve, critic and novelist

- George Sand, novelist

- Hippolyte Taine, writer on art and literature

- Gertrude Tennant, English society hostess

- Jeanne de Tourbey, successful demi-mondaine

- Jules Troubat, Sainte-Beuve's secretary

- Ivan Turgenev, Russian novelist

- Émile Zola, novelist[6][7][8][9][10][11]

Themes

Flaubert's personality was rigorously excluded from his novels, but in the letters, written at night after the day's literary work was done, he expresses much more spontaneously his own personal views.[12] Their themes often arise from his life as a reader and writer. They discuss the subject-matter and structural difficulties of his novels, and explore the problems Flaubert faced in their composition, giving the reader a unique glimpse of his art in the making.[13] They illustrate his extensive reading of the creative literatures of France, England (he loved Shakespeare, Byron and Dickens), Germany and the classical world; also his deep researches into history, philosophy and the sciences.[14][15] Above all, they constantly state and restate Flaubert's belief in the duty of the writer to maintain his independence, and in his own need to reach literary beauty through a quasi-scientific objectivity.[16][17][18]

But his letters also demonstrate an enjoyment of the simple pleasures of Flaubert's youth. Friendship, love, conversation, a delight in foreign travel, the pleasures of the table and of the bed are all in evidence.[19][20] These do not disappear in his maturer years, but they are offset by discussions of politics and current affairs which reveal an increasing disgust with society, especially bourgeois society, and with the age he lived in.[21][14] They exude a sadness and a sense of having grown old before his time.[22] As a whole, said the literary critic Eric Le Calvez, Flaubert's correspondence, "reveals his vision of life and of the relation between life and art: since the human condition is miserable, life can be legitimated only through an eternal pursuit of art."[14]

Critical reception

For many years after the first publication of the letters critical opinion was divided. Albert Thibaudet thought them "the expression of a first-rate intellect", and André Gide wrote that "For more than five years his correspondence took the place of the Bible at my bedside. It was my reservoir of energy". Frank Harris said that in his letters "he lets himself go and unconsciously paints himself for us to the life; and this Gustave Flaubert is enormously more interesting than anything in Madame Bovary".[23] On the other hand, Marcel Proust found Flaubert's epistolary style "even worse" than that of his novels, while for Henry James the Flaubert of the letters was "impossible as a companion".[24]

This ambivalence is a thing of the past, and there is now widespread agreement that the Flaubert correspondence is one of the finest in French literature.[14] Publication of them "has crowned his reputation as the exemplary artist".[25] Enid Starkie wrote that Flaubert was one of his own greatest literary creations, and that the letters might well be seen in the future as his greatest book, and the one in which "he has most fully distilled his personality and his wisdom".[26] Jean-Paul Sartre, an inveterate enemy of Flaubert's novels, considered the letters a perfect example of pre-Freudian free association, and for Julian Barnes this description "hints at their fluency, profligacy, range and sexual frankness; to which we should add power, control, wit, emotion and furious intelligence. The Correspondance...has always added up to Flaubert's best biography."[27][2] Rosemary Lloyd analyses the elements of their appeal as being "partly [their] wide sweep, partly the sense of seeing what Baudelaire called the strings and pulleys of the writer's workshop, and partly the immediacy of Flaubert's changeable, complex and challenging personality." She continues, "Reading Flaubert's correspondence brings startlingly alive a man of enormous complexity, of remarkable appetites and debilitating lethargies, a knotted network of prejudices, insights, blind spots, passions and ambitions."[28]

Editions

- Flaubert, Gustave (1887–1893). Correspondance. Paris: G. Charpentier. This four-volume edition was the first to try to collect Flaubert's letters. The unnamed editor was Flaubert's niece Caroline Commanville; she censored the letters freely, cutting out many passages which she thought indecent or which referred unflatteringly to living persons, especially to herself, and very often failing to notify the reader of these cuts by the use of ellipses. She also corrected his punctuation and sometimes "improved" his phrasing.[29][30][2][31]

- Flaubert, Gustave (1910). Correspondance. Paris: Conard. A five-volume edition which has been described as "seriously flawed".[32][31]

- Descharmes, René, ed. (1922–1925). Correspondance. Paris: Librairie de France. In four volumes. The first scholarly edition.[32][31]

- Flaubert, Gustave. Correspondance. Paris: Louis Conard. In nine volumes, containing 1992 letters. Most of the notes were taken from René Descharmes' edition.[17][31]

- Dumesnil, René; Pommier, Jean; Digeon, Claude, eds. (1954). Correspondance: Supplément. Paris: Louis Conard, Jacques Lambert. Adds 1296 letters to the edition of 1926–1933.[17][31]

- Bruneau, Jean, ed. (1973–2007). Correspondance. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. Paris: Gallimard. In five volumes, the first four edited by Jean Bruneau, and the fifth, which was published after Bruneau's death, co-edited with Yvan Leclerc (FR). This edition boasts an extremely thorough critical apparatus, with letters written to Flaubert, excerpts from the Goncourt Journal and other third-party documentation, together with explanatory and critical notes by the editor. Julian Barnes points out that in the third volume the appendices, notes and variants take up more pages than the letters themselves.[33][2][31]

- Bardèche, Maurice, ed. (1974–1976). Correspondance. Paris: Club de l'Honnête Homme. In five volumes.[31]

- Bonaccorso, Giovanni, ed. (2001). Correspondance. Première édition scientifique. Saint-Genouph: Nizet. Two volumes were published, taking the edition up to 1861, but the editor's death brought the project to a halt.[31]

- Leclerc, Yvan; Girard, Danielle, eds. (2 November 2017). "Correspondance: Édition électronique". Correspondence de Flaubert. Centre Flaubert, Université de Rouen. Retrieved 29 July 2018. A freely available Web-based edition comprising 4481 letters, 134 of which have not previously been published.[3][34]

There have also been many single-correspondent editions of Flaubert's letters to one or another of his friends and associates, and selections from the collected letters.[31]

Translations

- Tarver, John Charles (1895). Gustave Flaubert: As Seen in his Works and Correspondence. Westminster: A. Constable. The first selection of the letters in English.[35][36]

- The George Sand – Gustave Flaubert Letters. Translated by Mckenzie, Aimée L. London: Duckworth. 1922.[37]

- Rumbold, Richard, ed. (1950). Gustave Flaubert: Letters. Translated by Cohen, J. M. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. Includes 122 letters.[38]

- Steegmuller, Francis, ed. (1954). The Selected Letters of Gustave Flaubert. London: Hamish Hamilton. According to The Nation, Steegmuller "edited them with discretion after translating them with authority".[39][31]

- Steegmuller, Francis, ed. (1972). Flaubert in Egypt: A Sensibility on Tour. A Narrative Drawn from Gustave Flaubert's Travel Notes and Letters. Boston: Little, Brown.[40]

- Steegmuller, Francis, ed. (1979–1982). The Letters of Gustave Flaubert. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. In two volumes. Jean Bruneau, editor of the then half-completed Pléiade edition, gave Steegmuller unfettered access to all his files, including the manuscripts of newly-discovered letters, with the result that some appeared in Steegmuller's English before they had been published in the original French. Its publication, The Times later said, "was a major event in the English-speaking literary world".[41][2][42]

- Beaumont, Barbara, ed. (1985). Flaubert and Turgenev, a Friendship in Letters. The Complete Correspondence. London: Athlone.[43]

- Flaubert-Sand: The Correspondence. Translated by Steegmuller, Francis; Bray, Barbara. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1993. Includes about 100 letters not to be found in the 1922 Mckenzie translation. Barbara Bray translated George Sand's letters, and Francis Steegmuller Flaubert's. It has been called "a graceful and expressive translation in a scrupulous edition that has the effect of the best kind of biography – and a double one at that."[44][45]

- Selected Letters. Translated by Wall, Geoffrey. Baltimore: Penguin. 1997.[46]

Footnotes

- Leclerc, Yvan; Girard, Danielle, eds. (2 November 2017). "Présentation des lettres par ordre chronologique". Correspondence: Édition électronique (in French). Centre Flaubert, Université de Rouen. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Barnes 2003.

- Leclerc & Girard 2017.

- Porter, Laurence M.; Gray, Eugene F. (2002). Gustave Flaubert's Madame Bovary: A Reference Guide. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 145. ISBN 0313319162. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Leclerc, Yvan; Girard, Danielle, eds. (2 November 2017). "Présentation des lettres par destinataire". Correspondence: Édition électronique (in French). Centre Flaubert, Université de Rouen. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Steegmuller 1954, pp. 56–57.

- Flood, Alison (27 July 2009). "Letters Reveal Flaubert's English Amitié Amoureuse". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Steegmuller, Francis, ed. (1980). The Letters of Gustave Flaubert 1830–1857. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press. p. 222. ISBN 0674526368. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Steegmuller 1982, pp. 5, 18, 65 108, 133, 195, 219, 250, 251.

- Winock 2016, pp. 230, 312.

- Thorlby, Anthony, ed. (1969). The Penguin Companion to Literature. 2: European. Harmondsworth: Penguin. pp. 304, 686. ISBN 9780140510355. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Steegmuller 1954, p. 11.

- Lloyd 2004, p. 76.

- Le Calvez 2001, p. 74.

- Barnes 2002, p. 244.

- Steegmuller 1954, pp. 17–18.

- Le Calvez 2001, p. 75.

- Hampshire, Stuart (16 December 1982). "In Flaubert's Laboratory". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Lloyd 2004, p. 67.

- Vidal, Gore (1982). Pink Triangle and Yellow Star, and Other Essays (1976–1982). London: Heinemann. p. 29. ISBN 9780434830756. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Lloyd, Rosemary (2014) [1990]. Madame Bovary. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 9781138799349. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Lloyd 2004, p. 80.

- Harris, Frank (1927). Latest Contemporary Portraits. New York: Macaulay. p. 206.

- Steegmuller 1982, pp. xvii–xviii.

- Birch, Dinah, ed. (2009). "The Oxford Companion to English Literature (7 ed.)". Oxford Reference. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Starkie, Enid (1971). Flaubert the Master: A Critical and Biographical Study (1856-1880). London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 355–356. ISBN 0297002260.

- Barnes 2002, p. 239.

- Lloyd 2004, pp. 67, 83.

- Lloyd 2004, p. 68.

- Steegmuller 1982, pp. xv–xvi.

- Cléroux 2013.

- Winock 2016, p. 422.

- Barnes, Julian (14 March 2008). "The Lost Governess". TLS. London. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- Leclerc, Yvan; Girard, Danielle, eds. (2 November 2017). "Correspondance de Flaubert - Lettres Inédites". Correspondence: Édition électronique. Centre Flaubert, Université de Rouen. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- Winock 2016, p. 517.

- Goodman, Richard (2009). "The Hermit of Croisset: Flaubert's Fiercely Enduring Perfectionism" (PDF). English Faculty Publications. University of New Orleans. p. 4. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- Massardier-Kenney, Françoise (2000). Gender in the Fiction of George Sand. Amsterdam: Rodopi. p. 188. ISBN 9042007079. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- Cranston, Maurice (12 May 1950). "Flaubert's Letters". The Spectator: 26. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Sypher, F. J., ed. (1977). The Reader's Adviser: A Layman's Guide to Literature. Volume 2 (12th ed.). New York: Bowker. p. 213. ISBN 0835208524. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- Porter 2001, p. 354.

- "Francis Steegmuller". The Times. London. 27 October 1994. p. 21.

- Patton, Susannah (2010). A Journey into Flaubert's Normandy. Surry Hills, NSW: Accessible Publishing Systems. p. 248. ISBN 9781458785435. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Le Calvez 2001, p. 76.

- Fields, Beverly (7 March 1993). "Flaubert and Sand: Linked by Excellence". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Shattuck, Roger (21 February 1993). "Pen Pals par Excellence". New York Times. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Porter 2001, p. 355.

References

- Barnes, Julian (2002) [2001]. Something to Declare. Leicester: W F Howes. ISBN 1841975435.

- Barnes, Julian (28 June 2003). "Worlds Within Words". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Cléroux, Gilles (2013). "Correspondance de Gustave Flaubert: Bibliographie des éditions et des études (1884–2013)". Gustave Flaubert (in French). Centre Flaubert, Université de Rouen. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Le Calvez, Eric J (2001). "Correspondance". In Porter, Laurence M (ed.). A Gustave Flaubert Encyclopedia. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 031330744X. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Leclerc, Yvan; Girard, Danielle, eds. (2 November 2017). "Correspondence de Flaubert". Correspondence: Édition électronique (in French). Centre Flaubert, Université de Rouen. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Lloyd, Rosemary (2004). "Flaubert's Correspondence". In Unwin, Timothy (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Flaubert. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521815517. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Porter, Laurence M, ed. (2001). A Gustave Flaubert Encyclopedia. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 031330744X. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Steegmuller, Francis, ed. (1954). The Selected Letters of Gustave Flaubert. London: Hamish Hamilton. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Steegmuller, Francis, ed. (1982). The Letters of Gustave Flaubert 1857-1880. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674526406. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Winock, Michel (2016). Flaubert. Translated by Elliott, Nicholas. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674737952. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

External links

- The McKenzie translation of the Flaubert–Sand letters

- A digital edition of Flaubert's letters in the original French, by Yvan Leclerc and Danielle Girard