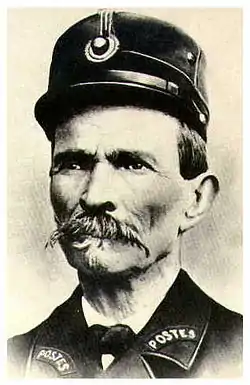

Ferdinand Cheval

Ferdinand Cheval (19 April 1836 – 19 August 1924) was a French postman who spent thirty-three years of his life building Le Palais idéal (the "Ideal Palace") in Hauterives.[1][2] The Palace is regarded as an extraordinary example of naïve art architecture.

Origins

Joseph Ferdinand Cheval, also known as Facteur Cheval (Postman/Mailman Cheval)[3] was born in Charmes-sur-l'Herbasse into a poor farming family.[4] He left school at the age of 13 to become a baker's apprentice, but eventually became a postman.[1][2]

In 1858, Cheval married his first wife, Rosaline Revol. Together they had two sons, Victorin Joseph Fernand (1864), and Ferdinand Cyril (1867). Victorin died in 1865 just a year after he was born. His first wife Rosaline died in 1873. Five years later Cheval met and married Claire-Philomène Richaud.[5] Because of his marriage to Claire, the new couple found themselves with a dowry that accompanied some land on which the Palais Idéal stands today.[3] Later that same year, Claire gave birth to their daughter Alice-Marie-Philomène. Alice died in 1894. Alice's death hit Cheval the hardest and she was the last child he would have. Many years would pass before his son Cyril and his second wife, Claire, would die within two years of each other in 1912 and 1914 respectively.[5]

Palais idéal

Cheval began the building in April 1879 when he was 43 years old.[6] He reported:

I was walking very fast when my foot caught on something that sent me stumbling a few meters away, I wanted to know the cause. In a dream I had built a palace, a castle or caves, I cannot express it well... I told no one about it for fear of being ridiculed and I felt ridiculous myself. Then fifteen years later, when I had almost forgotten my dream, when I wasn't thinking of it at all, my foot reminded me of it. My foot tripped on a stone that almost made me fall. I wanted to know what it was... It was a stone of such a strange shape that I put it in my pocket to admire it at my ease. The next day, I went back to the same place. I found more stones, even more beautiful, I gathered them together on the spot and was overcome with delight... It's a sandstone shaped by water and hardened by the power of time. It becomes as hard as pebbles. It represents a sculpture so strange that it is impossible for man to imitate, it represents any kind of animal, any kind of caricature. I said to myself: since Nature is willing to do the sculpture, I will do the masonry and the architecture.[7][8]

For the next thirty-three years, Cheval picked up stones during his daily mail round and carried them home to build the Palais idéal.[1] He spent the first twenty years building the outer walls. At first, he carried the stones in his pockets, then switched to a basket. Eventually, he used a wheelbarrow. He often worked at night, by the light of an oil lamp.[1][2]

The palace materials mainly consist of stones (river washed), pebbles, porous tufa and fossils of many different shapes and sizes. When a visitor first comes up on the palace, the first face they see is the southern facade spanning nearly 30 yards long and 14 yards high. The decoration resembles aspects of both the Brighton Pavilion and Gaudí's Sagrada Família. Cheval did not travel and he had even given himself the title of peasant, so even though the qualities resemble those pieces of art, he had never seen them prior.[6] Three giant stones, each with doll-like faces, standing close to 35 ft high serve not only as decoration but as a support system for the Barbary Tower, with an elegant spiral staircase lined with swans made of cement leading up to it.[4] The tall stones were named Vercingétorix, Archimedes and Caesar. Cheval hand-carved the names into each individual figure.[6]

The north face exhibits a long path dotted with large openings to provide plentiful light leading into the heart of the palace itself. This facade is very forest-like with walls coated in moss and massive seaweed. The ceiling, swirling patterns of pebbles and shells that outline the chandeliers. Upper walls are lined with horizontal bands with animals carved into them in an Egyptian-like style. Other animals on the north face facade include two ostriches (presumably mother and father) and an ostrich chick, a 4-foot tall camel,[6] flamingos, octopi, lions, dragons, and a polar bear.[4]

The east facade took the longest to build before, a shocking 20 years. This face includes 'The Temple of Nature', an Egyptian style temple-like structure supported by large, thick sandstone columns. It includes two waterfalls called the Source of Life and the Source of Wisdom.[3]

The Palais is a mix of different styles with inspirations from Christianity to Hinduism. Cheval bound the stones together with lime, mortar and cement.[1][2]

The palace is sprinkled with short quotes and poems hand-carved by Cheval himself. Some examples being "If you look for gold you will find it in elbow grease.", "The Pantheon of an obscure hero."[6] "The work of one man", "Out of a dream I have brought forth the Queen of the World", "This is of art, and of energy", "The ecstasy of a beautiful dream and the prize of effort", "Dream of a peasant", "Temple of Life", and "Palace of the Imagination".[4] Perhaps the most iconic phrase he inscribed on the wall reads "1879-1912 10,000 days, 93,000 hours, 33 years of struggle. Let those who think they can do better try."[6]

Burial

Cheval wanted to be buried in his palace. Because that is illegal in France, he spent eight more years building a mausoleum for himself in the Hauterives cemetery. He died on 19 August 1924, about a year after he had finished building it, and is buried there.[1][2]

Recognition

Just before his death, Cheval received recognition from figures including André Breton, Bernard Buffet, Jean Tinguely, Niki de Saint Phalle, Robert Doisneau, and Pablo Picasso.[9] His work is commemorated in an essay by Anaïs Nin. In 1932, the German artist Max Ernst created a collage titled The Postman Cheval. The collage belongs to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection and is on display there. In 1958, Ado Kyrou produced Le Palais idéal, a short film about Cheval's palace.

After admiring Cheval's work, Picasso created a series of drawings telling a narrative, in a cartoon fashion, which is now recognized as Facteur Cheval sketchbook in 1937. Picasso drew him as twisted, hybrid-like creature (or beast), carved with the initials of the French postal service (P.T.T) on his skin, dressed in typical postman's attire, holding masonry tools and a letter. The creature was standing in front of his creation. In the drawing, Picasso took a humorous route sketching Cheval's body in the shape of a horse and his head that of a bird. Picasso did this in an effort to make a sort of pun about Cheval's name and career given birds are messengers (as Cheval was a postman) and the meaning of Cheval is horse.[4]

In 1969, André Malraux, the Minister of Culture, declared the Palais a cultural landmark and had it officially protected.[2] In 1986, Cheval was put on a French postage stamp.[2]

In 2018, English singer-songwriter Will Varley included a song about Cheval and Palais idéal on his album Spirit of Minnie called The Postman.

In 2018 French director Nils Tavernier released the feature film L'incroyable histoire du facteur Cheval, English title: Ideal Palace, about Cheval's life and work, with Jacques Gamblin starring as Postman Cheval.[10]

Visiting hours

It is open to visitors every day except Christmas Day, New Year's Day and 15 to 31 January.

Gallery

Palais idéal

Palais idéal Hindu temple

Hindu temple Detail of north front

Detail of north front Swiss chalet

Swiss chalet

See also

References

- Palais Idéal: The postman’s palace, Interesting Thing of the Day, 15 August 2007.

- Mary Blum. "The postman who delivered a palace", New York Times, 3 May 2007

- "Ideal Palace: The naive dream of the Cheval Factor". AC Presse. 10 March 2019.

- Heuer, Elizabeth B. (Elizabeth Barnhart) (2008). Going postal : surrealism and the discourses of mail art. OCLC 303504101.

- "Ferdinand Cheval known as postman cheval". www.facteurcheval.com. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Pearson, Dan. "Treasure Trouve;the Palais Ideal, Hauterives, Drome, France;Gardening." The Times, 16 Jul 1995, pp. 1. ProQuest 318305846.

- Becker, Howard S. Art Worlds. University of California Press (1982), pp. 263–64.

- Pierre Chazaud, op. cit. (translated from French)

- "The Ideal Palace of the Horse Factor in Celebration." Le Monde , 23 Nov. 2019, pp. 27 . ProQuest 2316736583.

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt7248884/

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ferdinand Cheval. |

- Postman Cheval's website in English and French

- Le Palais Idéal du Facteur Cheval (requires Flash).

- Expo.htm at perso.wanadoo.fr" Expo Coco Peintre du Facteur Cheval-1987 Hauterives France

- Hauterives and Palais Idéal Photogallery

- Album Mon Cheval, a French blog's photogallery.