Faustulus

In Roman mythology, Faustulus was the shepherd who found the infant Romulus (the future founder of the city of Rome)[1] and his twin brother Remus along the banks of the Tiber River as they were being suckled by the she-wolf, Lupa.[2][3]According to legend, Faustulus carried the babies back to his sheepfold for his wife Acca Larentia to nurse them.[2] Faustulus and Acca Larentia then raised the boys as their own. Romulus later killed King Amulius of Alba Longa and his brother Remus before founding the city of Rome "in the place where they [Romulus and Remus] had been raised."[4]

Representation in Livy's From the Foundations of the City

The Roman historian, Livy, details the story of the infants Romulus and Remus in his work From the Foundations of the City (or, History of Rome). According to Livy, after the rape of the Vestal Virgin Rhea Silvia, whom later claimed Mars as the father (either out of truth or for the respectability that came of divine providence, as Livy points out), King Amulius, the twin's great-uncle, ordered the infants put into a basket and sent down the Tiber River to their deaths by drowning. In this year, the Tiber had flooded and as such, carried the boys into a flatland. When the water receded, it dropped the boys on a flat piece of land where the she-wolf, known as Lupa, found and nursed them. According to Livy, some shepherds referred to Acca Larentia as the 'she-wolf' because of her sexual promiscuity, and this may be how the tale of the twins suckling at the teat of the she-wolf came to be. Either way, Faustulus carried the infants back to his sheepfold where he presented the children to his wife to rear. Faustulus and Acca Larentia raised the boys as their own, and they grew to be shepherds. According to Livy, Faustulus was aware of the royal lineage of the twins from the beginning, writing:

"From the very beginning Faustulus had entertained the suspicion that they were children of the royal blood that he was bringing up in his house; for he was aware both that infants had been exposed by order of the king, and that the time when he had himself taken up the children exactly coincided with that event."[5]

Faustulus withheld his knowledge of the twin's lineage, choosing instead to wait "until opportunity offered or necessity compelled."[5] According to Livy, necessity came first, as Remus had been captured by Numitor, the former King, a descendant of Aeneas, father of Rhea Silvia, and maternal grandfather of Romulus and Remus.[6] Faustulus revealed the true nature of the twin's birth to Romulus. At the same time, Numitor realized the boy he held in custody was his grandson Remus, and so a plan was hatched to slay King Amulius. Romulus gathered a band of shepherds and, combined with Remus's forces from the house of Numitor, attacked and killed the king. The twins declared the death of the tyrant and named their grandfather king. According to Livy, this was followed by a "shout of assent...from the entire throng [which] confirmed the new monarch's title and authority."[5]

Representation in Plutarch's The Parallel Lives

Greek philosopher, biographer, and essayist Plutarch, addresses Faustulus in his section, The Life of Romulus, in his work The Parallel Lives. Plutarch largely follows Livy's description of Faustulus in his work, From the Foundations of the City, while offering some additional information and contending ideas. Plutarch notes that the servant whom King Amulius ordered to set the twins down the Tiber was referred to by some as Faustulus. Plutarch also claims that Numitor most likely knew of Faustulus and Acca Larentia's raising Romulus and Remus, and "secretly aided the foster-parents in their task."[7] According to Plutarch, Faustulus was at one point brought before Numitor to confirm the livelihood of the boys. [7]

Etymology

Faustulus' name being tied to that of faunus is generally rejected by the scholarship, with many detailing how Faustulus is derived from faveo (Latin: befriend, support, back up). The name Faustulus is further derived from favestos, as the "verbal adjective underlying his name, must be linked to the religious sense of faveo expressed in the ritual formula favete linguis"[8] meaning 'be silent'. These Latin roots help to explain why Faustulus remained silent about the nature of Romulus and Remus' lineage for so long. Many have historically viewed Faustulus as a "wolfish" character, but this has no historical or etymological basis, and is generally thought to be the result of popular association of fauna and Faustulus.[8]

Death

According to Plutarch, Faustulus, along with his brother Pleistinus, was killed in the same skirmish that resulted in Romulus slaying his brother Remus before the founding of the city of Rome.[7]

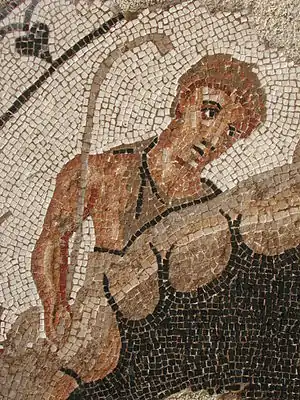

Representations in Art

Painted in 1654 by French artist, Nicolas Mignard, this example of late 17th century French art depicts Faustulus presenting the infants Romulus and Remus to his wife (their adoptive mother), Acca Larentia. This work is housed in the Dallas Museum of Art.

Painted in 1654 by French artist, Nicolas Mignard, this example of late 17th century French art depicts Faustulus presenting the infants Romulus and Remus to his wife (their adoptive mother), Acca Larentia. This work is housed in the Dallas Museum of Art. This 1597 work by Pietro de Cortona depicts the presentation of Romulus and Remus to his wife, Acca Larentia. This work is housed in the Denon wing of the Louvre.

This 1597 work by Pietro de Cortona depicts the presentation of Romulus and Remus to his wife, Acca Larentia. This work is housed in the Denon wing of the Louvre. Romulus and Remus by Peter Paul Rubens, 1615. One can view Faustulus (right) approaching the infants Romulus and Remus as they are suckling at the teat of the she-wolf. Housed in the Pinacoteca Capitolina in Rome.

Romulus and Remus by Peter Paul Rubens, 1615. One can view Faustulus (right) approaching the infants Romulus and Remus as they are suckling at the teat of the she-wolf. Housed in the Pinacoteca Capitolina in Rome. The Capitoline Wolf housed in Musei Capitolini, Rome, Italy, depicts the she-wolf, Lupa, suckling the mythical founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus.

The Capitoline Wolf housed in Musei Capitolini, Rome, Italy, depicts the she-wolf, Lupa, suckling the mythical founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus.

Notes

- Garcia, Brittany (18 April 2018). "Romulus and Remus". Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- Livy. From the Foundations of the City. pp. Book 1, Section 4.

- Plutarch. The Parallel Lives. p. 6.

- Livy. From the Foundations of the City. pp. Book 1, Section 6.

- "Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 1, chapter 1". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- "P. Ovidius Naso, Fasti, book 4". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- "Plutarch • Life of Romulus". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- Noonan, J. D. (1993). "Daunus/Faunus in "Aeneid" 12". Classical Antiquity. 12 (1): 111–125. doi:10.2307/25010986. ISSN 0278-6656.