Faro Ladies

Gaming in public was not acceptable for aristocratic women as it was for aristocratic men in 18th century England, who played at social clubs such as the Tory-affiliated White's or the Whig-affiliated Brooks's. Thus, women gambled in private houses at social gatherings that often provided other, more socially acceptable forms of entertainment, such as musical concerts or amateur theatricals.[1] A group of aristocratic women came to be well known for the faro tables they hosted late into the night. Mrs. Albinia Hobart (later Lady Buckinghamshire), Lady Sarah Archer, Mrs. Sturt, Mrs. Concannon, and Lady Elizabeth Luttrell were common figures in the popular press throughout the 1790s.

Gambling's reputation as a dual personal and social vice, especially female gambling, was not new to the late 18th century.[2] Charles Cotton’s The Compleat Gamester from 1674 was still widely cited during the era. However, in the 1790s the issue took on new importance as Britain, influenced by the chaos of the French Revolution, focused its attention with renewed vigor on any threatening domestic issue that could disrupt social order and political power.[3] Another factor contributing to a new focus on gaming was the increased importance of the middle classes in late eighteenth-century Britain. The middle class, who depended on credit for both livelihood and reputation, were particularly sour toward the vices in which the landed classes indulged, often without serious repercussions.[2] At the same time, the middle class's avid consumption of the public information about aristocratic gamblers provided by the press made possible their very notoriety.

Politics

In the Westminster election of 1784, Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, a renowned gambler who canvassed for Charles J. Fox, himself a notorious gamester (he in fact ran a faro table in his home from 1780–81), brought the issue of gaming into the popular media’s negative portrayal of the aristocracy's involvement in politics.[4] As a whole, the group aristocratic, gambling women were often associated with the Foxite Whigs.[5] Lady Archer canvassed for Charles Fox as well, as did the Duchess’s sister and Lady Duncannon. In other elections, Mrs. Hobart canvassed for Admiral Lord Hood and Sir Cecil Wray. The private version of gaming practiced in the Faro ladies’ homes, furthermore, was “a crucial component of the social forum through which women entered the politics,” because women participated in both the play and political discussion with each other and any males present.[6]

Legal Repercussions

Justice Ashurst was the first member of the judiciary to speak publicly about the private gambling houses, following George III's “Proclamation Against Vice” of 1792. He referenced statutes existent since the reign of Henry VIII and encouraged his audience, the Grand Jury of Middlesex county, to be “vigilant in its administration of the law.” Voicing the influence of Enlightenment ideals, he emphasized the irrationality of gambling in terms of the health of society.[7] The legislation concerning Faro in particular set a penalty of £200 for keeping a table and £50 for playing. A few years later, in 1796-97, increased monitoring of lower-class gambling brought about the arguably most famous legal admonishment of the Faro ladies. Henry Weston had committed forgery in order to obtain 100,000 pound from the Bank of England, and then lost the amount at a Faro bank. Lord Chief Justice Kenyon spoke out on May 7, 1796:

“If any prosecutions are fairly brought before me, and the parties are justly convicted, whatever may be their rank or station in the country, though they should be the finest ladies in the land, they shall certainly exhibit themselves at the pillory.”[8]

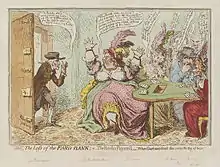

Caricaturists subsequently published prints depicting Mrs. Hobart and Lady Sarah Archer at the pillory, the victims of an unruly crowd in Gillray's The Exaltation of Faro’s Daughters and in Richard Newton's Female Gamblers in the Pillory, for example.

In early 1797, the discovery of the loss of the faro bank at one of the Ladies’ parties brought them to the forefront of the news once again. Conspicuously outed as a result of this incident, information against Lady Buckinghamshire, Lady Elizabeth Luttrell, Mrs. Sturt, and Mrs. Concannon, and the usual proprietor of their table, Henry Martindale, was heard before Conant, the magistrate of Marlborough Street.[9] The informants were two footmen previously in the service of Lady Buckinghamshire, and The Times reported on 13 March 1797 that “the evidence went to prove that the defendants had gaming parties at their different houses in rotation; and, that when they met at Lady B.’s, the witnesses used to wait upon them in the gambling room…” Martindale was charged £200, and all but Mr. Concannon £50.[10]

“Faro Ladies” and the press

.jpg.webp)

Anti-gaming literature in late eighteenth-century Britain, in the form of satirical prints, newspapers, and serious moral treatises, emphasized the moral, social and political problems associated specifically with female gaming. The growth of the press in the second half of the eighteenth century was a key element to the publicity of the Faro ladies. Scandalous gossip and news about the aristocracy and royalty became common knowledge to the literate public through newspapers and an increasingly popular art form, caricature prints.[11] These prints made the Faro ladies visible to anyone, literate or illiterate, who happened to be passing a print shop window. The print shops littered the neighborhood in which many of the aristocratic Faro ladies lived and played, St. James, and also middle and lower class neighborhoods, such as The Strand and Covent Garden.[12]

One caricaturist in particular, James Gillray, made Lady Buckinghamshire and Lady Archer's moral transgressions and gambling habits extremely visible.[13] Gillray's prints satirizing the Faro ladies include: Modern-Hospitality,—or—A Friendly Party in High Life (1792); The Exaltation of Faro’s Daughters (1796); Discipline a la Kenyon (1797); The Loss of the Faro-Bank; or—The Rook’s Pigeon’d (1792). Caricature prints often utilized pointed ironic discrepancies to satirize their subjects' vices. For example, in "The Exaltation of Faro's Daughters," irony manifests in the discrepancies between the print's image, public shaming on the elevated pillory, and the triple-entendre of “exaltation.” The ladies are physically exalted-raised up-but rather than accordingly esteemed in this position, are actually defamed by a wild crowd who pummel them with garbage and tomatoes. The word also suggests the “undue degree of pleasurable excitement”[14] that moral reformers associated with the dangerously sexual dimension of older women's exercise of power via morally reproachable modes such as gaming.

.jpg.webp)

Earlier examples from Gillray's predecessor William Hogarth include A Rake's Progress and The Cockpit (1759). Isaac Cruikshank's Dividing the Spoil!! (1796) leverages a scathing commentary on the propriety the Faro ladies have literally gambled away. In this print, four Faro ladies, including Mrs. Hobart and Lady Sarah Archer are compared to four prostitutes through the juxtaposed depiction of counting earnings over a table. The Faro ladies' portrait is labelled "St. James," a wealthy aristocratic neighborhood also home to royalty, while the prostitutes' portrait is labelled "St. Giles," a notoriously seedy London area.

John Ashton's The History of Gambling in England catalogues a series of extracts from The Morning Post and The Times, organs which the public accessed news of these “Faro ladies,” as they came to be called in the press. Other newspapers that contributed to wider knowledge of social scandal include the Public Advertiser, the Morning Chronicle, and the Morning Herald. The written press allowed the literate public to understand what issue the caricaturist's above were referencing in their prints.[15] Notes range from simple announcements, who opened their home that week for a Faro party, for example, to condemnations: “It is impossible to conceive a more complete system of fraud and dishonour than is practiced every night at the Faro Banks.” [16] However, coverage of the Faro ladies was ubiquitous enough such that all voices on the matter could be heard. A brief note in the “Fashion” section of World from 1791 reads:

“Dear Ladies of the METROPOLIS, study this PORTRAIT! With the Ladies of PARIS—the moments of improving dissipation are gone by, and a more solid and reasoning character has succeeded to them: but you are in the meridian of what is Ton, Taste, high Play, strict Honor, Faro Tables, Parental Affection, Lottery Insurances, and EXQUISITE SENSIBILITY. To jumble all these qualities properly together, forms at once the character of – a WOMAN OF CAPITAL FASHION! Follow and Embrace it! Be bold! Be desperate!”[17]

Moral Reformers

When personified, gambling was historically feminine, as “an enchanting witchery.” [18] In other words, “female emotionality, irrationality, and vulnerability” was linked to unpredictability and dangerous riskiness of games of chance.[19] Because a female banker at the Faro table not only played, but also controlled the game, critics saw the Faro ladies as particularly reprehensible examples of sexual misconduct. Women gamblers, after having lost their limited personal income (Pin-money), thus without legal or monetary credit to their name, could only wager their sexuality, i.e. their body. In satirical representations of aristocratic Faro ladies and the writings of moral reformers, prostitution was a common comparison, such as in Isaak Cruikshank's Dividing the Spoil!! (1796). Their sexual unnaturalness was also related to their apparent rejection of domestic duty and intent to exercise power in the public sphere, or at least on its male constituents. Male gamester, George Hanger, asked, for example, “Can any woman expect to give to her husband a vigorous and healthy offspring, whose mind, night after night, is thus distracted, and whose body is relaxed by anxiety and the fatigue of late hours?”[1]

Moral reformers such as Hannah More and William Wilberforce thus feared the Faro ladies power to seduce respectable men and disrupt the ordered distinction between the masculine public sphere and the feminine private sphere, maintained by the fidelity of each party to a marriage. The reformers noted misbehaving older women as bitter and lascivious, as predators who used gaming as a means to compete with young, respectable, fertile women who would maintain an orderly domestic life, upon which the upbringing of a respectable masculine, public sector depended.[20]

Furthermore, 18th-century social opinion held that the upper classes were to be morally sound role models for the middle and lower classes.[21] Thus, one of the reasons the Faro ladies were perceived to be so socially threatening derived from the public and political dimensions of their gaming.

Hannah More, for example, writes of gaming women in Strictures:

“[T]heir example to the young and inexperienced, who are looking about for some sanction to justify them in that which they were before inclined, but were too timid to have ventured upon without the protection of such unsullied names. Thus these respectable characters, without looking to the general consequences of their indiscretion, are thoughtlessly employed in breaking down, as it were, the broad fence which should ever separate two very different sorts of society, and becoming a kind of unnatural link between vice and virtue.” [22]

More subtitles her Strictures on the modern system of female education: “with a view on the principles and conduct prevalent among women of rank and fortune,” clearly allotting them responsibility in shaping the behavior of the lower classes via indirect influence. At the same time, More maintains the need for the "broad fence which should ever separate two very different sorts of society." Moral reformers were concerned with the possibility that gambling created for the inappropriate and "unnatural" mixing of classes.

Speaking specifically of women playing at private Faro tables, Patrick Colquhoun identified a similar problem with upper-class influence in A Treatise on the Police of the Metropolis writes:

“Evil example, when thus sanctioned by apparent respectability, and by the dazzling blandishment of rank and fashion, is so intoxicating to those who have either suddenly acquired riches, or who are young and inexperienced, that it almost ceases to be a matter of wonder that the fatal propensity to Gaming should become universal; extending itself over all ranks in Society in a degree scarcely to be credited, but by those who will attentively investigate the subject.”[23]

Colquhoun, like More, gestures to an associated problematic implication of the Faro ladies’ publicity, the loss of clear separation between the classes. According to the social conventions within the middle class, his fear was not ungrounded. The middle class's imitation of “gentility,” which was often practiced in the setting of gaming in private houses, began as a self-conscious mode of “commercial interaction,” became the “standard of expected behaviour.”[24] While in reality the middle class made the hospitability and sociality of gaming respectable within their credit-based ethic, the idea of influence and emulation was exploited by anti-gaming moral reformers. The anti-gaming literature posited that not only did the Faro ladies and their associates' vice undermine them as role models, it also muddled the ideally distinct lines separating classes and sexes. Accordingly, in some satirical prints, Faro ladies figured through tropes connoting poverty and vulgarity begged viewers to compare them to the poor in order to illustrate a “moral kinship with the lowest classes.”[25] In others, Lady Sarah Archer wears a riding dress to connote the masculine role she takes on through gambling.[26]

More generally, then, the way in which the Faro ladies gaming created a chorus of reactions from moral reformers, the popular press, and the judiciary speaks to Romantic culture's concern with the demarcation and dissolution of public from private, aristocratic from vulgar, male from female. Also, since Faro has such a low house 'edge', it provided more temptation to the banker to cheat, and Faro, in Europe or America, was seen as a cheaters game (see article on Faro (card game)). This added to the immoral image of those women who banked the game,

Additional Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Literary Portrayals of Faro Ladies

Mary Robinson, Nobody: A Comedy in Two Acts.[27] Drury Lane, 1794. Ed. Terry F. Robinson. Romantic Circles.

Charles Sedley, The Faro Table: or, The Gambling Mothers. A Fashionable Fable, 2 vols. (London, J.F. Hughes, 1808).

John Tobin's comedy The Faro Table: Or, the Guardians was written in the 1790s but not performed at Drury Lane because one of its characters, Lady Nightshade, explicitly alluded to Lady Sarah Archer. The play was staged after Tobin's death in 1816.[12]

“The Rape of the Faro-Bank: an Heroi-comical poem in Eight Cantos.” Anonymous, published following the reportedly stolen Faro Bank at Lady Buckinghamshire's residence.[28]

References

- Russell, Gillian. “Faro’s Daughters”: Female Gamesters, Politics, and the Discourse of Finance in 1790s Britain.” Eighteenth-Century Studies (2000): 33.4, p. 484.

- Donald, Diana. The Age of Caricature: Satirical Prints in the Reign of George III. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996, p. 106.

- Russell, Gillian. “Faro’s Daughters”: Female Gamesters, Politics, and the Discourse of Finance in 1790s Britain.” Eighteenth-Century Studies (2000): 33.4.

- Deutsch, Phyllis. "Moral Trespass in Georgian London" Gaming, Gender, and Electoral Politics in the Age of George III." The Historical Journal 39.3 (Sep., 1996), pp. 637-656.

- McCreery, Cindy. The Satirical Gaze: Prints of Women in Late Eighteenth-Century England. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., 2004, p. 237

- Deutsch, Phyllis. "Moral Trespass in Georgian London" Gaming, Gender, and Electoral Politics in the Age of George III." The Historical Journal 39.3 (Sep., 1996), pp. 647-649.

- Russell, Gillian. “Faro’s Daughters”: Female Gamesters, Politics, and the Discourse of Finance in 1790s Britain.” Eighteenth-Century Studies (2000): 33.4, p. 489.

- Russell, Gillian. “Faro’s Daughters”: Female Gamesters, Politics, and the Discourse of Finance in 1790s Britain.” Eighteenth-Century Studies (2000): 33.4, p. 490.

- Russell, Gillian. “Faro’s Daughters”: Female Gamesters, Politics, and the Discourse of Finance in 1790s Britain.” Eighteenth-Century Studies (2000): 33.4, p. 494 and Ashton, John. History of Gambling in England. London: Duckworth & Co., 1898, p. 78

- Ashton, John. History of Gambling in England. London: Duckworth & Co., 1898, p. 78.

- Hart, Katherine W. James Gillray: Prints by the Eighteenth-Century Master of Caricature. Hanover: Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, 2004, p. 26.

- Russell, Gillian. “Faro’s Daughters”: Female Gamesters, Politics, and the Discourse of Finance in 1790s Britain.” Eighteenth-Century Studies (2000): 33.4

- McCreery, Cindy. The Satirical Gaze: Prints of Women in Late Eighteenth-Century England. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., 2004,

- "Exaltation." Oxford English Dictionary Online, 2nd edition, Oxford University Press: 1989.

- Hart, Katherine W. James Gillray: Prints by the Eighteenth-Century Master of Caricature. Hanover: Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, 2004, p. 26.

- Ashton, John. History of Gambling in England. London: Duckworth & Co., 1898, p. 81.

- “Fashion” in World, Thursday, February 17, 1791, Issue 1289.

- Russell, Gillian. “Faro’s Daughters”: Female Gamesters, Politics, and the Discourse of Finance in 1790s Britain.” Eighteenth-Century Studies (2000): 33.4, p. 495, quoting Charles Cotton’s The Compleat Gamester (1674)

- Deutsch, Phyllis. "Moral Trespass in Georgian London" Gaming, Gender, and Electoral Politics in the Age of George III." The Historical Journal 39.3 (Sep., 1996), p. 647.

- McCreery, Cindy. The Satirical Gaze: Prints of Women in Late Eighteenth-Century England. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., 2004.

- McCreery, Cindy. The Satirical Gaze: Prints of Women in Late Eighteenth-Century England. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., 2004; Donald, Diana. The Age of Caricature: Satirical Prints in the Reign of George III. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996.

- More, Hannah. Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education. 5th ed. Dublin: 1800.

- Colquhoun, Patrick. A treatise on the police of the Metropolis; ... The sixth edition, corrected and considerably enlarged. London: 1800. pp. 139-140.

- Mullin, Janet E. "'We Had Carding':Hospitable Card Play and Polite Domestic Sociability Among the Middling Sort in Eighteenth-Century England." Journal of Social History 42.4 (Summer 2009): p. 991.

- Donald, Diana. The Age of Caricature: Satirical Prints in the Reign of George III. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996.

- McCreery, Cindy. The Satirical Gaze: Prints of Women in Late Eighteenth-Century England. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., 2004, p. 273.

- "Nobody: A Comedy in Two Acts". romantic-circles.org. Mar 1, 2013. Retrieved Oct 1, 2020.

- Donald, Diana. The Age of Caricature: Satirical Prints in the Reign of George III. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996, p. 106.

External links

Media related to Faro Ladies at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Faro Ladies at Wikimedia Commons- Introduction to Mary Robinson's Nobody by Terry F. Robinson. Features a discussion of the Faro Ladies.

- Contemporary Caricatures of the Faro Ladies