Farmington Mine disaster

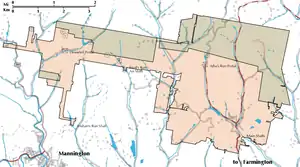

The Farmington Mine disaster was an explosion that happened at approximately 5:30 a.m. on November 20, 1968, at the Consol No. 9 coal mine north of Farmington and Mannington, West Virginia, United States.

Smoke and flames pouring from the Llewellyn shaft of the Consol No. 9 mine on November 20, 1968 | |

| Date | November 20, 1968 |

|---|---|

| Time | 5:30 a.m. |

| Location | Consol No. 9 coal mine north of Farmington and Mannington, West Virginia, United States |

| Cause | Coal Mine explosion |

| Casualties | |

| 78 dead | |

The explosion was large enough to be felt in Fairmont, almost 12 miles away. At the time, 99 miners were inside. Over the course of the next few hours, 21 miners were able to escape the mine, but 78 were still trapped. All who were unable to escape perished; the bodies of 19 of the dead were never recovered. The cause of the explosion was never determined, but the accident served as the catalyst for several new laws that were passed to protect miners.

Consol No 9

The Consol No. 9 mine was developed in the Pittsburgh coal seam, with its main entrances at James Fork, the confluence of Little Dunkard Mill Run and Dunkard Mill Run, 2 miles (3 kilometers) north of Farmington, West Virginia (39°32′19.09″N 80°15′14.44″W). The Pittsburgh seam is over 300 feet (90 meters) below the valley bottoms in this region, and is fairly uniform, generally about 10 feet (3 meters) thick.

This mine was originally opened in 1909 as the Jamison No. 9 Mine, operated by the Jamison Coal and Coke Company. The original entrance shafts were 322 feet deep. Even in 1909, it was noted that "gasses are liberating" from the coal in the mine, so that locked safety lamps were used at all times. Initially, compressed air power was used to undercut the coal, which was then blasted before horse power was used to haul the coal to the shaft, but within a year, compressed air locomotives were obtained for the mine railway.[1]

Between 1911 and 1929, Jamison No. 9 produced over 100,000 tons per year, except in 1922, when production was just under 3000 tons. Production fell to just over 4000 tons in early 1930, after which the mine was closed for three years. Production resumed in 1934, climbing to over 1.2 million tons per year in 1956.[2]

On November 14, 1954, an explosion ripped through the mine, killing 16 miners and leading to a temporary shutdown.[3][4] In addition to 16 deaths, the explosion destroyed the headframe of one mine shaft. The explosion occurred during pillar removal conducted as part of retreat mining.[5]

Under Consolidation Coal Company ownership, coal production in 1977 was 98772 tons.[6] This coal was produced as a byproduct of the recovery operation after the 1968 explosion.

Chronology

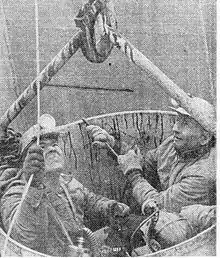

At 5:30 a.m on November 20, 1968 an explosion shook the mine. It was so strong that a motel clerk reported feeling vibrations 12 miles away. Miners living in the area heard the noise and, knowing what it meant, headed to the mine, where they discovered a rapidly spreading fire with flames shooting 150 feet into the air. Within hours, 21 miners made it to the surface but 78 were still trapped underground.[7]

The fires continued to burn for over a week, and on November 29, rescuers finally admitted defeat after air samples from drill holes showed air unable to sustain human life. The mine was sealed on November 30 with concrete to starve the fire of oxygen.[8]

In September 1969, the mine was unsealed in an attempt to recover the miners' bodies. Progress was slow because workers discovered cave-ins that they had to tunnel around. This recovery effort continued for almost ten years. By April 1978, 59 of the 78 bodies had been recovered.[9]

Victims

- Arthur A. Anderson Jr.

- Jack O. Armstrong*

- Thomas D. Ashcraft

- Jimmy Barr

- Orval D. Beam*

- John Joseph Bingamon*

- Thomas Boggess

- Louis S. Boros*

- Harold W. Butt

- Lee E. Carpenter

- David V. Cartwright

- William E. Currence*

- Dale E. Davis

- Albert R. DeBerry

- George O. Decker

- Howard A. Deel*

- James E. Efaw

- Joe Ferris

- Virgil "Pete" Forte*

- H. Wade Foster*

- Aulda G. Freeman Jr.*

- Robert L. Glover

- Forrest B. Goff

- John F. Gouzd

- Charles F. Hardman

- Ebert E. Hartzell

- Simon P. Hayes

- Paul F. Henderson*

- Roy F Henderson Sr.

- Steve Horvath

- Junior M. Jenkins*

- James Jones

- Pete J. Kaznoski Sr.*

- Robert D. Kerns

- Charles E. King

- James Ray Kniceley

- Charles Korsh Jr.

- George R. Kovar

- David Mainella Sr.

- Walter R. Martin

- Frank Matish*

- Hartsel L. Mayle

- Dennis N. McDonald

- Emilio D. Megna*

- Jack D. Michael*

- Wayne R. Minor

- Charles E. Moody

- Paul O. Moran

- Adron W. Morris

- Joseph Muto

- Randall R. Parsons

- Raymond R. Parsons

- Nicholas Petro

- Fred Burt Rogers

- William D. Sheme

- Robert J. Sigley

- Henry J. Skarzinski

- Russell D. Snyder

- John Sopuch*

- Jerry L. Stoneking

- Harry L. Strait

- Albert Takacs

- William L. Takacs*

- Dewey Tarley

- Frank Tate, Jr.

- Goy A. Taylor

- Hoy B. Taylor

- Edwin A. Tennant*

- Homer E. Tichenor

- Dennis L. Toler

- John W. Toothman

- Gorman H. Trimble

- Roscoe M. Triplett

- William T. Walker

- James H. Walter

- Lester B. Willard

- Edward A. Williams*

- Lloyd William Wilson

- Jerry R. Yanero

- Pete Zogel, Jr.

An asterisk ( * ) indicates the unrecovered.

Resulting governmental legislation

The Farmington disaster was a catalyst for the passage of major changes in U.S. mining safety law. One month after the disaster the U.S. Department of the Interior held a conference on mine safety. Stewart Udall's opening speech specifically referenced Farmington and concluded, "let me assure you, the people of this country no longer will accept the disgraceful health and safety record that has characterized this major industry." [10]

As a result of the Farmington disaster, the United States Congress passed the 1969 Coal Mine Safety and Health Act which strengthened safety standards, increased Federal mine inspections, and gave coal miners specific safety and health rights. In November of 1968 Davitt McAteer conducted a study of West Virginia mines after the Farmington disaster.

Investigation

In 1990, the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration investigation into the accident concluded in part that the ventilation in the mine “was inadequate overall, and most probably non-existent in some areas.”

In 2008, a memo written by an investigator in September 1970 came to light. In it, the inspector wrote that a safety alarm on a ventilation fan used to flush explosive methane gas from the mine had been disabled. “Therefore when the fan would stop there was no way of anyone knowing about it because the alarm signal was bypassed,” the inspector wrote.[11]

Litigation

Families of the miners that died in the blast were never compensated for their deaths. A lawsuit filed in Marion County Circuit Court on November 6, 2014, on behalf of the estates of dead miners, alleged that plaintiffs discovered in June that the mine’s chief electrician, Alex Kovarbasich, disabled a ventilation fan that contributed to the accident. The lawsuit further alleges that the mining company, Consolidation Coal Co., has concealed the identity of the manager since the accident.[12] After being transferred to federal district court due to diversity of plaintiffs' jurisdiction, the case was initially dismissed due to the statute of limitations around wrongful death suits in West Virginia. The suit was subsequently referred to the Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit due to a lack of precedent. The court determined that the statute of repose is an essential element of a wrongful death claim, and had since passed.[13]

References

- Annual Report, Department of Mines for the Year Ending June 30, 1910, West Virginia Department of Mines, Charleston News Mail Co, 1911. Third Section, Page 15.

- Jamison C. & C. Co. Mine Data Tonnage Reports, West Virginia Office of Miners' Health Safety and Training.

- West Virginia Coal Mine Disasters, West Virginia State Archives Collection.

- Map Showing Extent of Forces, Flame and Deep Fire Areas, and Location of Dust Sampling Points Following Explosion, November 13, 1954, No. 9 Mine, Jamison Coal and Coke Company, Farmington West Virginia, West Virginia Mine Information Database System

- H. B. Humphrey, Historical Summary of Coal Mine Explosions in the United States, Bureau of Mines Information Circular 7900, Government Printing Office, 1959; pages 249, 251-258.

- Consolidation Coal Co. Mine Data Tonnage Reports, West Virginia Office of Miners' Health Safety and Training.

- "Report on the Farmington Disaster". Charleston Gazette-. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "Report on the Farmington Disaster". Charleston Gazette-. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "Report on the Farmington Disaster". Charleston Gazette-. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- Lockard, Duane. Coal: A Memoir and Critique. Charlottesville, University Press of Virginia, 1998. p. 71.

- Ward Jr., Ken. "Lawsuit alleges cover-up after 1968 Farmington No. 9 Mine disaster". Charleston Gazette-Mail. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- https://blogs.wsj.com/law/2014/11/07/decades-after-deadly-w-va-mine-disaster-new-lawsuit-assigns-blame/

- https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/4626518/michael-d-michael-administrator-v-consolidation-coal-company/

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Farmington mine disaster. |