F. O. Matthiessen

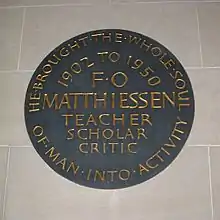

Francis Otto Matthiessen (February 19, 1902 – April 1, 1950) was an educator, scholar and literary critic influential in the fields of American literature and American studies.[1] His best known work, American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman, celebrated the achievements of several 19th-century American authors and had a profound impact on a generation of scholars. It also established American Renaissance as the common term to refer to American literature of the mid-nineteenth century. Matthiessen was known for his support of liberal causes and progressive politics. His contributions to the Harvard University community have been memorialized in several ways, including an endowed visiting professorship.

F. O. Matthiessen | |

|---|---|

Matthiessen (right) with Russell Cheney, Normandy, Summer 1925 | |

| Born | Francis Otto Matthiessen February 19, 1902 |

| Died | April 1, 1950 (aged 48) |

| Cause of death | Suicide by jumping from a height |

| Resting place | Springfield Cemetery, Springfield, Massachusetts |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Polytechnic and Hackley Schools |

| Alma mater | Yale, Oxford and Harvard |

| Occupation | Historian, literary critic, educator |

| Known for | American Renaissance |

| Partner(s) | Russell Cheney |

| Awards | DeForest and Alpheus Henry Snow Prizes, Rhodes Scholarship |

Early life and education

Matthiessen was born in Pasadena, California on February 19, 1902. He was the fourth of four children born to Frederick William Matthiessen (1868–1948) and Lucy Orne Pratt (1866). The family's three older siblings included Frederick William (1894), George Dwight (1897) and Lucy Orne (1898).[2]

In Pasadena he was a student at Polytechnic School. Following the separation of his parents, he relocated with his mother to his paternal grandparents home in LaSalle, Illinois. His grandfather, Frederick William Matthiessen, was an industrial leader in zinc production and a successful manufacturer of clocks and machine tools. He also served as mayor of Lasalle for ten years.[3] The grandson completed his secondary education at Hackley School, in Tarrytown, New York.

In 1923, Matthiessen graduated from Yale University, where he was managing editor of the Yale Daily News, editor of the Yale Literary Magazine and a member of Skull and Bones.[4] As the recipient of the university's Deforest Prize, he titled his oration, "Servants of the Devil", in which he proclaimed Yale's administration to be an "autocracy, ruled by a Corporation out of touch with college life and allied with big business".[5] In his final year as a Yale undergraduate, he received the Alpheus Henry Snow Prize,[6] awarded to the senior "who through the combination of intellectual achievement, character and personality, shall be adjudged by the faculty to have done the most for Yale by inspiring in classmates an admiration and love for the best traditions of high scholarship".

He studied at Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar, earning a B.Litt. in 1925. At Harvard University, he quickly completed his M.A. in 1926 and Ph.D. degree in 1927. He then returned to Yale to teach for two years, before beginning a distinguished teaching career at Harvard.

Scholarly work

Matthiessen was an American studies scholar and literary critic at Harvard University,[7] and chaired its undergraduate program in history and literature.[8] He wrote and edited landmark works of scholarship on T. S. Eliot, Ralph Waldo Emerson, the James family (Alice James, Henry James, Henry James Sr., and William James), Sarah Orne Jewett, Sinclair Lewis, Herman Melville, Henry David Thoreau, and Walt Whitman. His best-known book, American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman (1941), discusses the flowering of literary culture in the middle of the American 19th century, with Emerson, Thoreau, Melville, Whitman and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Its focus was the period roughly from 1850 to 1855 in which all these writers but Emerson published what would, by Matthiessen's time, come to be thought of as their masterpieces: Melville's Moby-Dick, multiple editions of Whitman's Leaves of Grass, Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter and The House of the Seven Gables, and Thoreau's Walden. The mid-19th century in American literature is commonly called the American Renaissance because of the influence of this work on later literary history and criticism. In 2003 The New York Times said that the book "virtually created the field of American literature."[1] Originally Matthiessen planned to include Edgar Allan Poe in the book, but found that Poe did not fit in the scheme of the book.[9] He wrote the chapter on Poe for the Literary History of the United States (LHUS, 1948), but "some of the editors missed the usual Matthiessen touch of brilliance and subtlety."[10] Kermit Vanderbilt suggests that because Matthiessen was "not able to pull together the related strands" between Poe and the writers of American Renaissance, the chapter is "markedly old-fashioned."[11] Matthiessen edited The Oxford Book of American Verse, published in 1950, an anthology of American poetry of major importance which contributed significantly to the propagation of American modernist poetry in the 1950s and 1960s.

Matthiessen was one of earliest scholars associated with the Salzburg Global Seminar. In July 1947, he gave the inaugural lecture, stating:

Our age has had no escape from an awareness of history. Much of that history has been hard and full of suffering. But now we have the luxury of an historical awareness of another sort, of an occasion not of anxiety but of promise. We may speak without exaggeration of this occasion as historic, since we have come here to enact anew the chief function of culture and humanism, to bring man again into communication with man.[12]

Along with John Crowe Ransom and Lionel Trilling, in 1948, Matthiessen was one of the founders of the Kenyon School of English.[13]

Politics

Matthiessen's politics were left-wing and socialist. Already financially secure, he donated an inheritance he received in the late 1940s to his friend, Marxist economist Paul Sweezy. Sweezy used the money, totalling almost $15,000, to found a new journal, which became the Monthly Review. On the Harvard campus, Matthiessen was a visible and active supporter of progressive causes. In May 1940 he was elected president of the Harvard Teachers Union, an affiliate of the American Federation of Labor. The Harvard Crimson reported his inaugural address in which Matthiessen quoted the campus union's constitution: "In affiliating with the organized labor movement, we express our desire to contribute to and receive support from this powerful progressive force; to reduce the segregation of teachers from the rest of the workers ...and increase thereby the sense of common purpose among them; and in particular to cooperate in this field in the advancement of education and resistance to all reaction."[14]

Matthiessen seconded the nomination of the Progressive Party presidential candidate, Henry Wallace, at the party's convention in Philadelphia in 1948.[15] Reflective of the emerging McCarthyism surveillance of left-wing university academics, he was mentioned as an activist in Boston area so-called "Communist front groups" by Herbert Philbrick.[16]

Personal life

Matthiessen was known to his friends as "Matty".[17] As a gay man in the 1930s and 1940s, he chose to remain in the closet throughout his professional career, if not in his personal life – although traces of homoerotic concern are apparent in his writings.[18] In 2009, a statement from Harvard University said that Matthiessen "stands out as an unusual example of a gay man who lived his sexuality as an 'open secret' in the mid-20th century."[7][8]

He had a two-decade-long romantic relationship with the painter Russell Cheney, twenty years his senior.[1] Like Matthiessen's family, Cheney's was prominent in business, being among America's leading silk producers. In a 1925 letter to Cheney, Matthiessen wrote about trusting friends with the knowledge of their relationship, rather than the world at large;[19] in planning to spend his life with Cheney, Matthiessen went as far as asking his cohort in the Yale secret society Skull and Bones to approve of their partnership.[20] With Cheney having encouraged Matthiessen's interest in Whitman, it has been argued that American Renaissance was "the ultimate expression of Matthiessen's love for Cheney and a secret celebration of the gay artist."[1][21][22] Throughout his teaching career at Harvard, Matthiessen maintained a residence in either Cambridge or Boston. However, the couple often retreated to their shared cottage in Kittery, Maine. Russell Cheney died in July 1945.

Death

Matthiessen committed suicide in 1950 by jumping from a 12th floor window of the Hotel Manger in Boston.[7][1] He had been hospitalized once for a nervous breakdown in 1938–39. He also continued to be deeply affected by Russell Cheney's death. He spent the evening before his death at the home of his friend and colleague, Kenneth Murdock, Harvard's Higginson Professor of English Literature.

In a note left in the hotel room, Matthiessen wrote, "I am depressed over world conditions. I am a Christian and a Socialist. I am against any order which interferes with that objective."[23] Commentators have speculated on the impact of the escalating Red Scare on his state of mind. He was being targeted by anti-communist forces that would soon be exploited by Senator Joseph McCarthy, and inquiries by the House Un-American Activities Committee into his politics may have been a contributing factor in his suicide. In an article subsection titled "Dupes and Fellow Travelers Dress Up Communist Fronts" in the April 4, 1949 edition of Life magazine, he had been pictured among fifty prominent academics, scientists, clergy and writers, who also included Albert Einstein, Arthur Miller, Lillian Hellman, Langston Hughes, Norman Mailer and fellow Harvard professors, Kirtley Mather, Corliss Lamont and Ralph Barton Perry.[24] Writing in 1958, Eric Jacobsen referred to Matthiessen's death as "hastened by forces whose activities earned for themselves the sobriquet un-American which they sought so assiduously to fasten on others".[25] However, in 1978, Harry Levin was more skeptical, saying only that "spokesmen for the Communist Party, to which he had never belonged, loudly signalized his suicide as a political gesture".[20]

Matthiessen was buried at Springfield Cemetery in Springfield, Massachusetts.[26]

Legacy

Matthiessen's contribution to the critical celebration of 19th-century American literature is considered formative and enduring. Along with several other scholars, he is regarded as a contributor to the creation of American studies as a recognized academic discipline. His personal story, academic contributions, political activism and early death had a lasting impact on a circle of scholars and writers. Their sense of loss and struggle to understand his suicide can be found in two novels with central figures inspired by Matthiessen, May Sarton's Faithful are the Wounds (1955)[27] and Mark Merlis's American Studies (1994).[28] John William Ward was his student.

His stature and legacy as a member of the Harvard community has been memorialized in several ways by the university. He was the first Senior Tutor at Eliot House, one of Harvard College's undergraduate residential houses. Approaching seventy years after his death, Matthiessen's suite at Eliot House remains preserved as the F. O. Matthiessen Room, housing personal manuscripts and 1700 volumes of his library available for scholarly research by permission.[29][30] Eliot House also hosts an annual Matthiessen Dinner with a guest speaker.

In 2009, Harvard established an endowed chair in LGBT studies called the F. O. Matthiessen Visiting Professorship of Gender and Sexuality.[7][8][31] Believing the post to be "the first professorship of its kind in the country",[7] Harvard President Drew Faust called it "an important milestone".[8][31] It is funded by a $1.5 million gift from the members and supporters of the Harvard Gender and Sexuality Caucus.[7][8][31][32][33]

Holders of the chair have included:

- 2013: Henry D. Abelove[34]

- 2014: Gayle Rubin[35]

- 2016: Robert Reid-Pharr[36]

- 2018: Omise'eke Natasha Tinsley[37]

Several generations after Matthiessen's death, this visiting professorship reaffirms the university's appreciation for his continuing legacy as a storied scholar and teacher.

Bibliography

- Sarah Orne Jewett, ISBN 0844613053, Peter Smith, (1929)

- Translation: An Elizabethan Art, ISBN 0781270340, (January 1931)

- The Achievement of T. S. Eliot: An Essay on the Nature of Poetry, Oxford University Press (1935)

- American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman, ISBN 0-19-500759-X, Oxford University Press (1941) (also available in many other editions)

- Herman Melville: Selected Poems, edited, New Directions (1944)

- Henry James: The Major Phase, ISBN 0195012259, Oxford University Press (June 1944)

- Russell Cheney, 1881–1945: A Record of His Work, Oxford University Press (1947)

- The Notebooks of Henry James, edited by F. O. Matthiessen and Kenneth B. Murdock, (first edition 1947) ISBN 0-226-51104-9, University of Chicago Press (1981)

- From the Heart of Europe, Oxford University Press (1948)

- The Education of a Socialist, Monthly Review, Vol 2 No 6, October 1950 (posthumous)

- Of Crime and Punishment, Monthly Review, Vol 2 No 6, October 1950 (posthumous)

- The Oxford Book of American Verse, ISBN 0195000498, Oxford University Press (December 1950)

- Responsibilities of the Critic, ISBN 0195000072, Oxford University Press (posthumous - 1952)

- The James Family: A Group Biography, ISBN 0715638386, Alfred A. Knopf (1947, posthumous - 1961)

- To the Memory of Phelps Putnam, essay in The Collected Poems of H. Phelps Putnam, ISBN 0374126275, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux (posthumous - 1971)

Footnotes

- Smith, Dinitia (May 29, 2003). "American Culture's Debt To Gay Sons of Harvard". The New York Times. NYTimes.com. Retrieved June 3, 2006.

- The Ancestry and the Descendants of John Pratt of Hartford, Conn Retrieved December 21, 2013

- "newspaper obituary". February 11, 1918. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- Yale University obituary mssa.library.yale.edu, Retrieved December 21, 2013

- Max Lerner: Pilgrim in the Promised Land, Retrieved December 21, 2013

- "Biography of F. O. Matthiessen". Harvard Gay and Lesbian Caucus. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- Steinberg, Jacques (June 3, 2009). "Harvard to Endow Chair in Gay Studies". The New York Times. NYTimes.com. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- Jan, Tracy (June 3, 2009). "Harvard to endow professorship in gay studies". The Boston Globe. Boston.com. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- Kermit Vanderbilt, American Literature and the Academy: The Roots, Growth, and Maturity of a Profession., p. 501. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. ISBN 0-8122-1291-6

- Vanderbilt 1986, p. 502

- Vanderbilt 1986, 523

- Salzburg Global Seminar History Archived 2013-12-25 at the Wayback Machine www.salzburgglobal.org, Retrieved September 5, 2013

- Kenyon School of English Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine www.kenyonhistory.net, Retrieved September 5, 2013

- Matthiessen Heads Union The Harvard Crimson, Retrieved March 22, 2013

- Memories of the Moderns, pg. 218, Retrieved December 21, 2013

- Philbrick, Herbert A. (1952). I Led 3 Lives: citizen, "Communist," counterspy. New York: McGraw-Hill.

matthiessen.

- Phelps, Christopher (May 1999). "Introduction: a Socialist Magazine in the American Century". Monthly Review. 51 (1): 2. doi:10.14452/MR-051-01-1999-05_1.

- "American Renaissance (New York: Oxford University Press, 1941), p. 431".

- Stein, Marc (2004). Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender History in America. 2. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 238. ISBN 0684312611.

In the same letter to Cheney (7 February 1925), Matthiessen makes clear a distinction between the world and those 'close friends' with whom he thinks it safe to share the fact of their relationship.

- Levin, Harry. "The Private Life of F. O. Matthiessen." New York Review of Books 25:12 (July 20, 1978), pp. 42–46 (abstract online; full text for subscribers only).

- Bergman, David (January 1, 1991). Gaiety Transfigured: Gay Self-Representation in American Literature. The University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-13050-9.

- Shand-Tucci, Douglass (May 19, 2003). The Crimson Letter: Harvard, Homosexuality and the Shaping of American Culture. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-19896-5.

- "F. O. Matthiessen Plunges to Death from Hotel Window". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- "Red Visitors Cause Rumpus". Life Magazine. April 4, 1949. p. 43. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- Jacobsen, Eric (1958). Translation: a Traditional Craft. Copenhagen: Gyldendalske Boghandel. pp. 9–10.

- Find A Grave - F. O. Matthiessen Retrieved April 29, 2013

- Harrington, Michael (Summer 1955). "Fictional Biography". New International. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- Baltimore Sun Retrieved November 25, 2013

- "Eliot Book Room Exhibits Treasures". Harvard Crimson. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

- "Eliot House - Facilities". eliot.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on January 1, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- Associated Press (June 3, 2009). "Harvard to Endow Chair in Gay, Lesbian Studies". FOXNews.com. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- "Harvard Gay & Lesbian Caucus: F. O. Matthiessen Visiting Professorship of Gender and Sexuality". HGLC.org. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- "About our name change from HGLC to HGSC". Retrieved June 6, 2018.

- Ferreol, Michelle Denise L. (October 4, 2012). "Harvard Establishes the First LGBTQ Faculty Position in the United States". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences Registrar's Office Archived 2013-12-02 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved November 25, 2013

- "Robert Reid-Pharr Named 2016 Matthiessen Professor". Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- "F. O. Matthiessen Visiting Professorship of Gender and Sexuality". Retrieved June 6, 2018.

Further reading

- Monthly Review, Vol 2 No 6, October 1950, entire edition dedicated to FOM with two essays by FOM and essays and statements by friends and scholars including Leo Marx, Paul Sweezy, Alfred Kazin, Corliss Lamont, Kenneth Murdock, May Sarton and Richard Wilbur

- Arac, Jonathan. "F. O. Matthiessen: Authorizing an American Renaissance." The American Renaissance Reconsidered. Eds. Walter Benn Michaels and Donald Pease. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1985.

- Hyde, Louis, ed. Rat and the Devil: Journal Letters of F. O. Matthiessen and Russell Cheney. Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Books, 1978. ISBN 1-55583-110-9; ISBN 0-208-01655-4.

- Leverenz, L. David. Manhood and the American Renaissance. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1989.

- Levin, Harry. "The Private Life of F. O. Matthiessen." New York Review of Books 25:12 (July 20, 1978), pp. 42–46 (abstract online; full text for subscribers only).

- Marcus, Greil. The Old Weird America New York: Henry Holt (Picador), pp. 90, 124

- Phelps, Christopher (May 1999). "Introduction: a Socialist Magazine in the American Century". Monthly Review. 51 (1): 1. doi:10.14452/MR-051-01-1999-05_1.

- Reynolds, David. Beneath the American Renaissance: The Subversive Imagination in the Age of Emerson and Melville. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1988.

- Spark, Clare, "F. O. Matthiessen: martyr to McCarthyism?". YDS: The Clare Spark Blog, December 29, 2010

- Stern, Frederick C., F. O. Matthiessen - Christian Socialist as Critic. Chapel Hill, North Carolina : University of North Carolina Press, 1981.

- Sundquist, Eric J. To Wake the Nations: Race and the Making of American Literature. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1993.

- Toibin, Colm. "Love in a Dark Time". New York, Scribner, 2004.

- Ward, John William 1955.Andrew Jackson, Symbol for an Age. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Marx, Leo. 1964. The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ward, John William 1969 Red, White, and Blue: Men, Books, and Ideas in American Culture . New York: Oxford University Press

External links

- F. O. Matthiessen at Find a Grave

- Gayle Rubin's faculty page at the University of Michigan's website Retrieved November 25, 2013

- Henry Abelove's faculty page at Wesleyan University's website Retrieved April 4, 2012

- A public conversation with Henry Abelove on YouTube, reflections on Matthiessen from 11:48 through 19:10 minutes, YouTube, Harvard's Carr Center for Human Rights Policy, Retrieved March 22, 2013

- F. O. Matthiessen Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.