F-algebra

In mathematics, specifically in category theory, F-algebras generalize the notion of algebraic structure. Rewriting the algebraic laws in terms of morphisms eliminates all references to quantified elements from the axioms, and these algebraic laws may then be glued together in terms of a single functor F, the signature.

F-algebras can also be used to represent data structures used in programming, such as lists and trees.

The main related concepts are initial F-algebras which may serve to encapsulate the induction principle, and the dual construction F-coalgebras.

Definition

If C is a category, and F: C → C is an endofunctor of C, then an F-algebra is a tuple (A, α), where A is an object of C and α is a C-morphism F(A) → A. The object A is called the carrier of the algebra. When it is permissible from context, algebras are often referred to by their carrier only instead of the tuple.

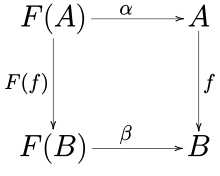

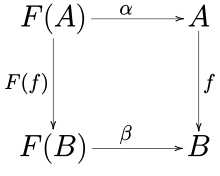

A homomorphism from an F-algebra (A, α) to an F-algebra (B, β) is a C-morphism f: A→B such that f ∘ α = β ∘ F(f), according to the following commutative diagram:

Equipped with these morphisms, F-algebras constitute a category.

The dual construction are F-coalgebras, which are objects A* together with a morphism α* : A* → F(A*).

Examples

Groups

Classically, a group is a set G with a binary operation m : G × G → G, satisfying three axioms:

- associativity: ∀ x∈G, ∀ y∈G, ∀ z∈G, m(m(x, y), z) = m(x, m(y, z)),

- identity element: ∃ 1∈G, ∀ x∈G, m(1, x) = m(x, 1) = x,

- inverse element: ∃ 1∈G, ∀ x∈G, ∃ x−1∈G, m(x−1, x) = m(x, x−1) = 1.

Note that the closure axiom is included in the symbolic definition of m.

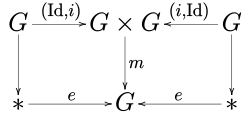

To treat this in a categorical framework, we first define the identity and inverse as morphisms e and i respectively. Let C be an arbitrary category with finite products and a terminal object *. The group G is an object in C. The morphism e sends each element in * to 1, the identity element of the group G. The morphism i sends each element x in G to its inverse x−1, satisfying m(x−1, x) = m(x, x−1) = 1. Then a group G can be defined as a 4-tuple (G, m, e, i), which describes a monoid category with only one object G. Each morphism f in this monoid category has an inverse f−1 that satisfies f−1 ∘ f = f ∘ f−1 = Id.[1]

It is then possible to rewrite the axioms in terms of morphisms:

- ∀ x∈G, ∀ y∈G, ∀ z∈G, m(m(x, y), z) = m(x, m(y, z)),

- ∀ x∈G, m(e(*), x) = m(x, e(*)) = x,

- ∀ x∈G, m(i(x), x) = m(x, i(x)) = e(*).

Then remove references to the elements of G (which will also remove universal quantifiers):

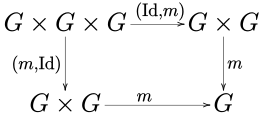

- m∘(m, Id) = m∘(Id, m),

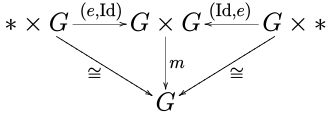

- m∘(e, Id) = m∘(Id, e) = Id,

- m∘(i, Id) = m∘(Id, i) = e.

Which is the same as claiming commutativity for the following diagrams:[2]

Now use the coproduct (the disjoint union of sets) to glue the three morphisms in one: α = e + i + m according to

This defines a group as a F-algebra where F is the functor F(G) = 1 + G + G × G.

Note 1: The above construction is used to define group objects over an arbitrary category with finite products and a terminal object *. When the category admits finite coproducts, the group objects are F-algebras. For example, finite groups are F-algebras in the category of finite sets and Lie groups are F-algebras in the category of smooth manifolds with smooth maps.

Algebraic structures

Going one step ahead of universal algebra, most algebraic structures are F-algebras. For example, abelian groups are F-algebras for the same functor F(G) = 1 + G + G×G as for groups, with an additional axiom for commutativity: m∘t = m, where t(x,y) = (y,x) is the transpose on GxG.

Monoids are F-algebras of signature F(M) = 1 + M×M. In the same vein, semigroups are F-algebras of signature F(S) = S×S

Rings, domains and fields are also F-algebras with a signature involving two laws +,•: R×R → R, an additive identity 0: 1 → R, a multiplicative identity 1: 1 → R, and an additive inverse for each element -: R → R. As all these functions share the same codomain R they can be glued into a single signature function 1 + 1 + R + R×R + R×R → R, with axioms to express associativity, distributivity, and so on. This makes rings F-algebras on the category of sets with signature 1 + 1 + R + R×R + R×R.

Alternatively, we can look at the functor F(R) = 1 + R×R in the category of abelian groups. In that context, the multiplication is a homomorphism, meaning m(x + y, z) = m(x,z) + m(y,z) and m(x,y + z) = m(x,y) + m(x,z), which are precisely the distributivity conditions. Therefore, a ring is an F-algebra of signature 1 + R×R over the category of abelian groups which satisfies two axioms (associativity and identity for the multiplication).

When we come to vector spaces and modules, the signature functor includes a scalar multiplication k×E → E, and the signature F(E) = 1 + E + k×E is parametrized by k over the category of fields, or rings.

Algebras over a field can be viewed as F-algebras of signature 1 + 1 + A + A×A + A×A + k×A over the category of sets, of signature 1 + A×A over the category of modules (a module with an internal multiplication), and of signature k×A over the category of rings (a ring with a scalar multiplication), when they are associative and unitary.

Lattice

Not all mathematical structures are F-algebras. For example, a poset P may be defined in categorical terms with a morphism s:P × P → Ω, on a subobject classifier (Ω = {0,1} in the category of sets and s(x,y)=1 precisely when x≤y). The axioms restricting the morphism s to define a poset can be rewritten in terms of morphisms. However, as the codomain of s is Ω and not P, it is not an F-algebra.

However, lattices in which every two elements have a supremum and an infimum, and in particular total orders, are F-algebras. This is because they can equivalently be defined in terms of the algebraic operations: x∨y = inf(x,y) and x∧y = sup(x,y), subject to certain axioms (commutativity, associativity, absorption and idempotency). Thus they are F-algebras of signature P x P + P x P. It is often said that lattice theory draws on both order theory and universal algebra.

Recurrence

Consider the functor that sends a set to . Here, denotes the category of sets, denotes the usual coproduct given by the disjoint union, and is a terminal object (i.e. any singleton set). Then, the set of natural numbers together with the function —which is the coproduct of the functions and —is an F-algebra.

Initial F-algebra

If the category of F-algebras for a given endofunctor F has an initial object, it is called an initial algebra. The algebra in the above example is an initial algebra. Various finite data structures used in programming, such as lists and trees, can be obtained as initial algebras of specific endofunctors.

Types defined by using least fixed point construct with functor F can be regarded as an initial F-algebra, provided that parametricity holds for the type.[3]

See also Universal algebra.

Terminal F-coalgebra

In a dual way, a similar relationship exists between notions of greatest fixed point and terminal F-coalgebra. These can be used for allowing potentially infinite objects while maintaining strong normalization property.[3] In the strongly normalizing Charity programming language (i.e. each program terminates in it), coinductive data types can be used to achieve surprising results, enabling the definition of lookup constructs to implement such “strong” functions like the Ackermann function.[4]

Notes

- Section I.2, III.6 in Mac Lane, Saunders (1988). Categories for the working mathematician (4th corr. print. ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90035-7.

- The vertical arrows without labels in the third diagram must be unique since * is terminal.

- Philip Wadler: Recursive types for free! University of Glasgow, June 1990. Draft.

- Robin Cockett: Charitable Thoughts (ps and ps.gz)

References

- Pierce, Benjamin C. (1991). "F-Algebras". Basic Category Theory for Computer Scientists. ISBN 0-262-66071-7.

- Barr, Michael; Wells, Charles (1990). Category theory for computing science. New York: Prentice Hall. p. 355. ISBN 0131204866. OCLC 19126000.

External links

- Categorical programming with inductive and coinductive types by Varmo Vene

- Philip Wadler: Recursive types for free! University of Glasgow, June 1990. Draft.

- Algebra and coalgebra from CLiki

- B. Jacobs, J.Rutten: A Tutorial on (Co) Algebras and (Co) Induction. Bulletin of the European Association for Theoretical Computer Science, vol. 62, 1997

- Understanding F-Algebras by Bartosz Milewski