Euphrates Handmade Syrian Horses and Riders

The Euphrates Handmade Syrian Horses and Riders (EU_HSHR's ) are zoomorphic clay figurines representing both solely horses or horses provided with riders and dating from the late Iron Age period (mid 8th–7th centuries BCE). These figurines are produced in the Middle Euphrates region and they belong to a production comprehending some anthropomorphic specimens, i.e. the Euphrates Syrian Pillar Figurines (EU_SPF's).

Other names in literature

The actual nomenclature adopted for this class of figurines has been recently proposed in a doctoral research.[1] Their current name recalls their geographic origin, the manufacturing technique, and the portrayed subjects. However, one may find their appearance in literature with different nomenclatures:

Technical characteristics

Modelling

The clay figurines are completely handmade and free standing. They were usually held with one hand with the other one engaged in modelling details. This was the so-called “snowman” technique, which allows working figurines in a three-dimensional space. The object is shaped all-around, preferring the under part of the figurine’s body as base of support. Unlike figurines made with molds, these figurines could be viewed from all sides, although the side is the preferred view. This production is characterized by abundant decorations directly applied on the figurine’s body through strips and blobs of clay. None figurine with traces of paint has been observed.[5]

Decorations and colours

This production is characterized by abundant decorations directly applied on the figurine’s body through strips and blobs of clay. Decorations are used to stress anatomical features and fabric patterns of attires for the riders and harnesses for the horses. The fabric colours of the clay are quite uniform, suggesting that the figurines were all well-fired, minor changes could be related to the atmosphere in the kilns. This evidence may also suggest the common use of kilns with the contemporary Neo-Assyrian pottery. The connection with the Neo-Assyrian pottery is further proved by the surface treatments, usually a pale brown slip and, in a few figurines, a cast of blue-green glaze. Indeed, this surface treatment usually appear in the local ceramic assemblage in imported pottery from Assyria and in some polychrome bricks. None figurine with traces of colours in surface has been observed.[6]

Geographical spread

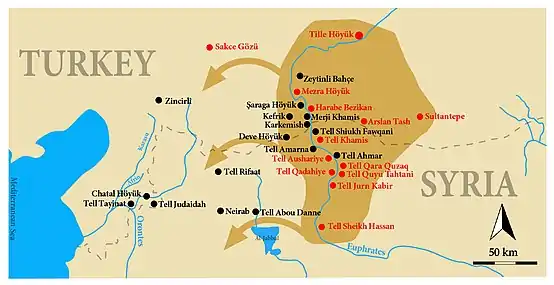

EU_HSHR's figurines are attested only west of the Euphrates and in particular, the Euphrates band seems to be the main productive centre. From this area several specimens have been collected at Karkemish, Tell Ahmar, Tell Amarna, Deve Höyük, Tell Shiukh Fawqani, Saraga Höyük, and Zeytinli Bahçe Höyük. This production has been linked only to those sites with a strong Neo-Assyrian presence as a result of prolonged control of some urban-sized centres on the Euphrates. Indeed, these figurines do not appear in other nearby sites where the Neo-Assyrian invasion caused a socio-economic impoverishment. These are sites such as Tell Sheikh Hassan, Tell Qara Quzaq, Tell Qara Quyu Tahtani, and Tell Khamis. Outside the Euphrates’ catchment area, sporadic finds are spread towards West in sites like Zincirli Höyük, Tell Judaidah, Chatal Höyük, Tell Tayinat, Tell Abu Danne, and likely in Tell Rifaat and Neirab.[7]

Chronology

According to contextual data, these figurines are attested in some Middle Euphrates sites during the mature Iron Age. In archaeological contexts, such artefacts usually come from upper layers dating from the Neo-Assyrian period (7th century BCE), but the origin of this production may be identified at the end of Neo-Syrian period (mid/end-8th century BCE). Indeed, at the site of Karkemish the major part of finds belonged to Iron III layers, while a minor part was retrieved in Iron II ones.[8]

Museums collections

See also

Notes

- Bolognani, B. 2017, pp. 45,177.

- Moorey, P.R.S 1980, pp. 100–102; 2005, pp. 225, 228.

- Pruss, A. 2010, pp. 231–246.

- Clayton, V. 2001; 2013, pp. 13, 25–38.

- Bolognani, B. 2020a, p.220; 2020b, p.44.

- Bolognani, B. 2020a, pp.220-221; 2020b, pp.44-45.

- Bolognani, B. 2020b, pp.46.

- Bolognani, B. 2020b, pp.44-45.

- Padovani, C. 2019, p. 82, fig. 36.

- Bolognani, B. 2017, cat. no. 835

- Bolognani, B. 2017, cat. nos. 799–803.

- Ornan, T. 1986, pp. 46, 62 left

References

- Bolognani, B. 2017, The Iron Age Figurines from Karkemish (2011–2015 Campaigns) and the Coroplastic Art of the Syro-Anatolian Region, unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Bologna, Bologna. Bolognani 2017_thesis

- Bolognani, B. 2020a, "The Iron Age Female Figurines from Karkemish and the Middle Euphrates Valley. Preliminary Notes on Some Syrian Pillar Figurines", in Donnat S., Hunziker-Rodewald R., Weygand I. (eds), Figurines féminines nues : Proche-Orient, Égypte, Nubie, Méditerranée, Asie centrale (VIIIe millénaire av. J.-C. - IVe siècle ap. J.-C.), Proceedings of the International Conference “Figurines féminines nues. Proche-Orient, Egypte, Nubie, Méditerranée, Asie centrale”, June 25th-26th 2015, MISHA, Strasbourg, Études d’archéologie et d’histoire ancienne (EAHA), De Boccard, Paris, pp. 209-223.Bolognani 2020a

- Bolognani, B. 2020b, "Figurines as Social Markers: The Neo-Assyrian Impact on the Northern Levant as Seen from the Material Culture", in Gavagnin K., Palermo R. (eds), Imperial Connections. Interactions and Expansions from Assyria to the Roman Period. Proceedings of the 5th “Broadening Horizons” Conference, 5-8 June 2017, Udine(West & East Monografie 2), University of Udine, Udine, pp. 43-57.Bolognani 2020b

- Clayton, V. 2001. Visible Bodies, Resistant Slaves: Towards an Archaeology of the Other: The 7th Century Figurines from Tell Ahmar, unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Melbourne, School of Fine Arts, Classical Studies and Archaeology, Melbourne.

- Clayton, V. 2013. Figurines, Slaves and Soldiers. The Iron Age Figurines from the Euphrates Valley, North Syria, K&H Publishing, Victoria.

- Moorey P.R.S. 1980, Cemeteries of the First Millenium B.C. at Deve Huyuk, near Carchemish. Salvaged by T.E. Lawrence and C.L. Woolley in 1913 (with a catalogue raisonne of the objects in Berlin, Cambridge, Liverpool, London and Oxford)(«BAR» 87), Bar Publishing, Oxford.

- Moorey P.R.S. 2005, Ancient Near Eastern Terracottas: With a Catalogue of the Collection in the Ashmolean Museum, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

- Ornan, T. 1986, A Man and His Land, Highlights from the Moshe Dayan Collection (Israel Museum Catalogue 270), The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

- Padovani, C. 2019, "36.Cavalier", in Blanchard, V. (ed.), Royaumes oubliés. De l'empire hittite aux Araméens, Liénart, Musée du Louvre, Paris, p. 82.

- Pruss A. 2010, Die Amuq-Terrakotten. Untersuchungen zu den Terrakotta-Figuren des 2. und 1. Jahrtausends v.Chr. aus dem Grabungen des Oriental Institute Chicago in der Amuq-Ebene,(Subartu 26), Brepols, Turnhout.