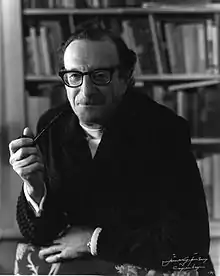

Eric Berne

Eric Berne (May 10, 1910 – July 15, 1970) was a Canadian-born psychiatrist who created the theory of transactional analysis as a way of explaining human behavior.

Eric Berne | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Eric Lennard Bernstein May 10, 1910 |

| Died | July 15, 1970 (aged 60) |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Known for | Developed the theory of Transactional analysis |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychiatry |

| Influences | Sigmund Freud, Erik Erikson, Wilder Penfield, René Spitz |

| Influenced | Thomas Anthony Harris, Albert Mehrabian, Claude Steiner |

Berne's theory of transactional analysis was based on the ideas of Freud but was distinctly different. Freudian psychotherapists focused on talk therapy as a way of gaining insight to their patient's personalities. Berne believed that insight could be better discovered by analyzing patients’ social transactions.[1]

Berne was the first psychiatrist to apply game theory to the field of psychiatry.

Background and education (1927–1938)

Eric Berne was born on May 10, 1910 in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, as Eric Lennard Bernstein. He was the son of David Hillel Bernstein, MD, a general practitioner, and Sarah Gordon Bernstein, a professional writer and editor. His only sibling, his sister Grace, was born five years later. The family immigrated to Canada from Poland and Russia. Both parents graduated from McGill University in Montreal. Eric was close to his father and spoke fondly of how he accompanied his father on rounds, traveling by horse-pulled sleigh on cold Montreal winters to visit patients.[2]

Berne's father died of tuberculosis when Berne was 11. His mother then supported herself and her two children working as an editor and writer. She encouraged her son to follow in his father's footsteps and to study medicine.[2] Berne received his baccalaureate degree in 1931[3] and an M.D. and C.M. (Master of Surgery) from McGill University Medical School in 1935.[2]

Berne came to the United States in 1935 when he began an internship at Englewood Hospital in New Jersey. After completing his one-year internship in 1936, he began his psychiatric residency at the Psychiatric Clinic of Yale University School of Medicine, where he worked for two years.[2]

In 1939, Berne became an American citizen and shortened his name from Eric Lennard Bernstein to Eric Berne.

In 1949, he was admitted as a Fellow in the American Psychiatric Association.[2]

Career (1938–1970)

From 1938-40, Berne was an assistant physician at Ring Sanitarium, Arlington Heights, Massachusetts.[4]

From 1940-43 he was employed as a psychiatrist in a sanitarium in Connecticut, and concurrently as a clinical assistant in psychiatry at Mt Sinai Hospital in New York. He also maintained a private practice.[4]

In 1943, during World War II, Berne joined the United States Army Medical Corps and served as a psychiatrist. He rose from the rank of Lieutenant, to Captain, and then to Major.[4] His assignments included Spokane, Washington, Ft. Ord, California and Brigham City, Utah.[2]

After his discharge in 1946, he settled in Carmel, California, and resumed his psychoanalytic training that he had begun in New York City, prior to the War, at the San Francisco Psychoanalytic Society and Institute.[2] In 1947-1949 Berne studied under Erik Erikson.[2]

From 1949 to 1964, Berne had a private practices in both Carmel and San Francisco and kept up a demanding pace of research, teaching in addition.[2]

He took an appointment in 1950 as Assistant Psychiatrist at Mt. Zion Hospital, San Francisco, and simultaneously began serving as a Consultant to the Surgeon General of the US Army.[2]

In 1951, he accepted a position of Adjunct and Attending Psychiatrist at the Veterans Administration and Mental Hygiene Clinic, San Francisco.[2]

The years from 1964 to 1970 were restless ones for Berne. His personal life became chaotic and he concentrated on his writing.[2]

Transactional analysis

Berne created the theory of transactional analysis as a way to explain human behavior. Berne's theory was based on the ideas of Freud but were distinctly different. Freudian psychotherapists focused on patient's personalities. Berne believed that insight could be better discovered by analyzing patients’ social transactions.[1] Berne mapped interpersonal relationships to three ego-states of the individuals involved: the Parent, Adult, and Child state. He then investigated communications between individuals based on the current state of each. He called these interpersonal interactions transactions and used the label games to refer to certain patterns of transactions which popped up repeatedly in everyday life.

The origins of transactional analysis can be traced to the first five of Berne's six articles on intuition, which he began writing in 1949. Even at this early juncture and while still working to become a psychoanalyst, his writings challenged Freudian concepts of the unconscious.[5]

In 1956, after 15 years of psychoanalytic training, Berne was refused admission to the San Francisco Psychoanalytic Institute as a fully-fledged psychoanalyst. He interpreted the request for several more years of training as a rejection and decided to walk away from psychoanalysis.[4] Before the end of the year, he had written two seminal papers, both published in 1957.

- In the first article, Intuition V: The Ego Image, Berne referenced P. Federn, E. Kahn, and H. Silberer, and indicated how he arrived at the concept of ego states, including his idea of separating "adult" from "child."

- The second paper, Ego States in Psychotherapy, was based on material presented earlier that year at the Psychiatric Clinic, Mt. Zion Hospital, San Francisco, and at the Langley Porter Neuropsychiatric Clinic, U.C. Medical School. In that second article, he developed the tripartite scheme used today (Parent, Adult, and Child), introduced the three-circle method of diagramming it, showed how to sketch contaminations, labeled the theory, "structural analysis," and termed it "a new psychotherapeutic approach."

A few months later, he wrote a third article, titled Transactional Analysis: A New and Effective Method of Group Therapy, which was presented by invitation at the 1957 Western Regional Meeting of the American Group Psychotherapy Association of Los Angeles. With the publication of this paper in the 1958 issue of the American Journal of Psychotherapy, Berne's new method of diagnosis and treatment, transactional analysis, became a permanent part of the psychotherapeutic literature. In addition to restating his concepts of ego states and structural analysis, the 1958 paper added the important new features of transactional analysis proper (i.e. the analysis of transactions), games, and scripts.[5]

His seminar group from the 1950s developed the term transactional analysis (TA) to describe therapies based on his work. By 1964, this expanded into the International Transactional Analysis Association. While still largely ignored by the psychoanalytic community, many therapists have put his ideas in practice.

In the early 1960s he published both technical and popular accounts of his conclusions. His first full-length book on TA was published in 1961, titled Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy.[3] Structures and Dynamics of Organizations and Groups (1963) examined the same analysis in a broader context than one-on-one interaction.

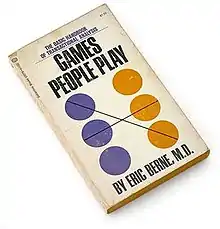

Games People Play

Games People Play: The Psychology of Human Relationships is a bestselling 1964 book by Dr. Eric Berne that has sold more than five million copies.[6] The book describes both functional and dysfunctional social interactions.

The essence of games described by Berne are that they are not zero-sum games (i.e. one must win at the other's expense), where the person who benefits from a transaction wins the game. On the contrary, the "games people play" usually pay all of the players off, even those who ostensibly are the losers, since they are about psychic equilibrium or promoting adopted self-damaging social roles instead of rational benefits. These payoffs are not consciously sought by the players but they are leading to the ultimate unconscious life script of each as set by their parental family interactions and favored emotions.

Despite having been written for professional therapists, the book became a New York Times bestseller and made Berne famous.[3] The book clearly presented everyday examples of the ways in which human beings are caught up in the games they play. Berne gave these games memorable titles such as "Now I've Got You, You Son of a Bitch", "Wooden Leg", "Why Don't You... / Yes, But...", and "Let's You and Him Fight".

Some of this terminology became a part of popular American vocabulary.

Berne said that ‘any social intercourse (…) has a biological advantage over no intercourse at all’, so, people need any form of ‘stroking’ (a physical contact, e.g., exchange) to live.[7]

Name and pseudonyms

In 1943 he changed his legal name from Eric Lennard Bernstein to Eric Berne.[8]

Berne had an irrepressible sense of humour, which was particularly evident in his writing. For example, in his article entitled Who was condom? Berne wrote about the contraceptive, the condom, and whether a man named Condom ever existed.[4] While at McGill he wrote for several student newspapers using pseudonyms. He continued to write under pseudonyms such as Cyprian St. Cyr ("Cyprian Sincere") in whimsical articles in the Transactional Analysis Bulletin.

Personal life

Berne was married three times. His first wife was Ruth Harvey (the Jorgensen biography used the pseudonyms of “Elinor” and “McRae” to protect the privacy of Berne’s first wife). They married in 1942, had two children, and divorced acrimoniously in 1945.[8] In 1949 he married Dorothy DeMass Way, with whom he also had two children before their divorce in 1964.[8] After his popular success, Eric married a third time, to Torre Peterson in 1967. The couple took up residence in Carmel, California, where he wrote, but he continued some clinical work in San Francisco. This marriage also ended in divorce, in early 1970.

Death

Berne died of a heart attack in Carmel on July 15, 1970.[3]

Bibliography

- The Mind in Action; 1947, New York, Simon and Schuster.

- The Structures and Dynamics of Organizations and Groups; 1961; (1984 Paperback reprint: ISBN 0-345-32025-5).

- Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy; 1961; (1986 reprint: ISBN 0-345-33836-7).

- Games People Play: the Psychology of Human Relations; 1964 (1978 reprint, Grove Press, ISBN 0-345-17046-6); (1996 Paperback, ISBN 0-345-41003-3)

- Principles of Group Treatment; 1966 Oxford University Press ISBN 019501118X ISBN 978-0195011180

- The Happy Valley; 1968, Random House Publisher, ISBN 0-394-47562-3

- Sex in Human Loving; 1970.

- A Layman's Guide to Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis (Paperback); 1975, Grove Press; ISBN 0-394-17833-5

- What Do You Say After You Say Hello?; 1973; ISBN 0-553-23267-3

- A Montreal Childhood; 2010, Seville (Spain), Editorial Jeder. ISBN 978-84-937032-4-0

References

- Footnotes

- "Transactional Analysis". disorders.org. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- Calcaterra, Nicholas Berne. "Biography of Eric Berne". ericberne.com. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- Stewart, Ian (1992). Eric Berne: Volume 2 of Key Figures in Counselling and Psychotherapy. London: Sage Publications. ISBN 0-8039-8466-9.

- Heathcote, Ann. "Eric Berne: A biographical sketch". European Association for Transactional Analysis. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2015-10-15.

- Staff writer. "Eric Berne, Founder". itaaworld.org. The International Transactional Analysis Association. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- Berne, Eric (1964). Games People Play – The Basic Hand Book of Transactional Analysis. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-41003-3.

- "D. Walczak. 2015. The process of exchange, solidarity and sustainable development in building a community of responsibility. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6 (1S1):506". Archived from the original on 2015-02-08. Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- Rosner, Rachael (2005), "Eric Berne", in Carnes, Mark Christopher; Betz, Paul R. (eds.), American National Biography: Supplement, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-522202-4

Further reading

- Jorgensen, Elizabeth Watkins; Jorgensen, Henry Irvin (1984), Eric Berne, Master Gamesman: A Transactional Biography, New York: Grove Press, ISBN 0-394-53846-3

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Eric Berne |