Engineer Cantonment

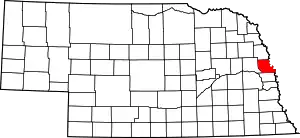

Engineer Cantonment is an archaeological site in Washington County, in the state of Nebraska in the Midwestern United States. Located in the floodplain of the Missouri River near present-day Omaha, Nebraska, it was the temporary winter camp of the scientific party of the Yellowstone Expedition. From October 1819 to June 1820, the party studied the geology and biology of the vicinity, and met with the local indigenous peoples. Their eight-month study of the biota has been described as "the first biodiversity inventory undertaken in the United States".[2]

Engineer Cantonment | |

Excavations at Engineer Cantonment, 2015 | |

Washington County, Nebraska | |

| Nearest city | Fort Calhoun, Nebraska |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 15000795[1] |

| Added to NRHP | November 17, 2015 |

The site was not used again after the departure of the expedition, and its location was forgotten. In 2003, it was rediscovered, and investigated during the 2003–05 archaeological seasons. In 2015, it was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

History

The 1803 purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France gave the United States a claim to the watershed of the Missouri River. The Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804–06 discovered abundant fur-trapping resources in the region. President Thomas Jefferson was eager to see these resources exploited, believing that fur trappers and traders with the local indigenous peoples would serve as the vanguard of American expansion into the new territory.[3]

The 1812–15 War of 1812 between the U.S. and the British Empire impeded the former's exploitation of the upper Missouri basin's fur-trapping potential. After the war ended, the U.S. remained concerned about British incursions onto American-claimed territory and British influence over the native peoples of the region.[4][5][6] In 1818, to counteract this British influence, and to protect American territory and fur-trapping activity in the upper Missouri watershed, President James Monroe and Secretary of War John C. Calhoun proposed, and Congress authorized, the Yellowstone Expedition. Over 1000 soldiers, led by Colonel Henry Atkinson, were ordered to travel up the Missouri and establish a chain of forts in its upper reaches.[7][8][9]

Long expedition

Atkinson's military expedition was joined by a scientific one, under the direction of Major Stephen H. Long. A member of the U.S. Army's topographical engineers, Long had explored and mapped portions of the Mississippi River basin in 1817, ranging from Fort Smith on the Arkansas River to Fort St. Anthony at the confluence of the Minnesota and the Mississippi Rivers. In early 1817, he had suggested to President-elect Monroe that an expedition be mounted to explore and map the Great Lakes and the upper Mississippi watershed by steamboat. He had repeated this proposal to Calhoun in 1818, with the addition of a party of scientists, and won approval. In the spring of 1819, Calhoun modified the plan, directing Long's party to accompany the Atkinson expedition up the Missouri.[9][10]

Long assembled a company of distinguished scientists for his expedition. The party included William Baldwin, doctor and botanist; Augustus Edward Jessup, geologist; Thomas Say, zoologist; Titian Peale, assistant naturalist; and Samuel Seymour, artist. The quintet has been described as "the largest and best-trained group of civilian scientists and investigators to accompany any government-sponsored expedition up to that time".[11]

Calhoun authorized Long to design and build a special steamboat for the expedition.[12] The vessel, the Western Engineer, was constructed in Pittsburgh in 1818–19. One of the first stern-wheelers ever built, it was 75 feet (23 m) long, with a beam of 13 feet (4.0 m), and a draft of only 19 inches (48 cm). To impress the indigenous peoples who beheld it, it bore "an elegant flag representing a white man and an Indian shaking hands, the calumet of peace and the sword",[13] and the bow was formed in the shape of "a huge serpent, black and scaly ... his mouth open, vomiting smoke".[14]

Up the Missouri

The Western Engineer, bearing the Long party, left Pittsburgh in the spring of 1819.[15] It descended the Ohio River and steamed up the Mississippi to St. Louis, near the confluence of the Missouri and the Mississippi.[16] In June 1819, the Long party started up the Missouri.[17]

.png.webp)

Progress upstream was slow. The river's strong current limited the vessel's average speed to less than three miles per hour (five kilometers per hour), and silt from the muddy waters clogged the steamboat's boiler. The party also made a number of stops, including one of a week at Franklin in the present-day state of Missouri.[9][12][18][19]

The expedition lost one of its members in Franklin. Baldwin, the surgeon and botanist, had long suffered from tuberculosis. Failing health forced him to leave the expedition, and he died several weeks later in Franklin.[18][20]

The military expedition under Atkinson made no better progress. Of the five steamboats hired to carry the force upstream, two apparently never reached the Missouri; another gave out and had to be left behind 30 miles (50 km) below Franklin; and the remaining two had to be abandoned a short distance above the mouth of the Kansas River. The expedition was forced to carry out the last leg of the journey on keelboats, which the soldiers towed from the banks using long ropes.[21][22]

Engineer Cantonment

On September 17, 1819, the Long party reached Fort Lisa, a fur-trading post located a few miles north of present-day Omaha, Nebraska. On September 19, the group established its winter quarters about half a mile (about three-quarters of a kilometer) above Ft. Lisa. This temporary post was dubbed Engineer Cantonment, after the Western Engineer.[2][16][23]

The military contingent under Atkinson was slower arriving. They reached the vicinity of present-day Fort Calhoun, Nebraska, a few miles upstream from Engineer Cantonment, in late September or early October;[24] there, they established Cantonment Missouri. Intended to be a permanent post, Cantonment Missouri was destroyed by floods the following spring, and abandoned in favor of a new site, Fort Atkinson, atop the bluffs and out of the floodplain.[22][25]

Long remained at Engineer Cantonment until October, when he returned eastward. He was accompanied by geologist Jessup, who had resigned from the expedition. Major Thomas Biddle, the keeper of the scientific expedition's official journal, had quarrelled with Long and was transferred to the military expedition late in 1819. Say, Peale, and Seymour spent the winter at Engineer Cantonment, as did Long's assistant James Duncan Graham, mapmaker and engineer William Henry Swift, six civilian members of the Western Engineer's crew, and a nine-man military guard.[12][26][27][28]

The party at Engineer Cantonment spent the next half-year exploring the vicinity of the camp. They held councils with the Pawnees and with the Otoes, visited Pawnee and Omaha villages, and were visited by members of other indigenous groups. They determined the camp's latitude and longitude, and investigated the geology and the biota of the area.[23][29][30]

1820 and thereafter

Long returned to Engineer Cantonment on May 27, 1820, accompanied by two new members of the party. Dr. Edwin James was to act as the expedition's surgeon, geologist, and botanist, thus replacing both Baldwin and Jessup. Captain John R. Bell was to keep the official journal, replacing Biddle.[27][29]

Long also brought a new set of orders from Washington. While there, he had attempted to secure additional funding from Calhoun, with limited success. Budgetary constraints arising from the Panic of 1819 led to a reduction in the size and scope of the expedition. Rather than continuing to ascend the Missouri, the Long party was to follow the Platte River upstream to its source, then work southward along the front of the Rocky Mountains to the headwaters of the Arkansas and the Red Rivers, then follow those rivers downstream to the Mississippi.[30][31][32]

The Long expedition left Engineer Cantonment on June 6, 1820. It did not return to the camp, and history does not record use of the site by anyone else after their departure.[33]

Biology

The scientific party's eight-month stay at Engineer Cantonment produced what has been called "the first biodiversity inventory undertaken in the United States".[35] Expeditions such as Lewis and Clark's, while investigating the biota of the regions through which they passed, had only spent a short time in any one location. This was the case with Long's expedition in the second half of 1820: the need to cover distance quickly precluded the thorough investigation of any one locale. By contrast, the long stay at Engineer Cantonment allowed the party to study the local biota in detail, and to try to produce a complete inventory of the plants and animals of the area.[36]

The party's study of the local flora was limited. The loss of Baldwin en route to Engineer Cantonment had left them without a botanist; James, his replacement, did not arrive until a short time before the departure of the summer 1820 expedition. A total of 51 plants in 34 families were described, four of which were thought to be new to science.[37][38]

Say, who has been called "the father of American entomology",[39] described the new animals found at the site. These included 46 insects in 30 families, 38 of them thought to be new to science. Other animals described include 143 birds, 4 of them thought to be new; 33 mammals, 6 of them new; 14 reptiles and 2 amphibians, all previously known; and 14 snails, 1 of them thought to be new.[37][38]

Since 1820

.jpg.webp)

The habitat and the biota of the area have changed significantly since 1820. At the time of the Long expedition, the Missouri was a meandering stream subject to spring flooding, moving through a wide floodplain with oxbow lakes and palustrine wetlands. Frequent prairie fires prevented the growth of extensive woodlands: the river valley was characterized by scattered groves, the bluffs that bounded it were not densely wooded, and the prairie west of the bluffs was entirely treeless. Since then, the river has been straightened and confined to a single channel. Dams built upstream control flooding. The wetlands of the floodplain have been drained and converted to farmland. Fire suppression has allowed the growth of riparian forests dominated by cottonwood, and the bluffs are now heavily wooded.[40][41]

Several species recorded at Engineer Cantonment are no longer present in the area. Two birds, the passenger pigeon and the Carolina parakeet, are entirely extinct. The local subspecies of gray wolf, Canis lupus nubilus, is likewise extinct. Several more of the larger carnivores, including black bear, eastern spotted skunk, and river otter, are no longer found in the vicinity; the mountain lion vanished from the area for many years, but in the early 21st century was once again found in eastern Nebraska. Hunting and destruction of habitat have led to the disappearance of three major herbivores: American bison, pronghorn, and elk.[42]

Two bat species, the eastern pipistrelle and the evening bat, have established themselves in the vicinity. The preferred habitat of both species is forest and forest edge, and in Nebraska their range has expanded from the extreme southeast corner of the state to cover the entire eastern third. This phenomenon has been observed with other birds, mammals, and insects of the eastern woodlands: their ranges have expanded with the spread of riparian forest upstream along prairie rivers.[35]

Two forest-dwelling rodent species documented at Engineer Cantonment, the eastern chipmunk and the eastern gray squirrel, have not expanded their range in the area, but have vanished since 1820. It has been suggested that although the increase in forest cover would seem to provide them with more habitat, the change in forest composition has been unfavorable to them: they prefer mature oak-hickory woods to the cottonwood forest that has grown up along the Missouri.[43]

Archaeology

History records no further use of the Engineer Cantonment site after 1820. With the passage of years, the location was forgotten. During the 20th century, there were some desultory attempts to find it; the failure of these led to the general belief that the remains of the site had been obliterated by flooding and cutting of the river, by quarrying operations, or by other modern development.[44]

In 2002, the Nebraska State Historical Society (NSHS) undertook an archaeological sampling survey in the greater Omaha area; it was thought that Engineer Cantonment and Fort Lisa might be found in the northern part of the study area. Planned improvements to a county road also called for an assessment of the impact on local cultural sites.[45]

While at Engineer Cantonment, Peale had produced several sketches of the camp and its surroundings. In early 2003, when the trees on the bluffs were bare, NSHS archaeologists saw that a stretch of the bluffs appeared to match Peale's drawing, including a wide ravine that Peale had depicted behind the camp. A trench was dug at the putative site, which produced limestone fragments, some discolored by burning, possibly remnants of a fireplace. Screening of dirt taken from the trench in the area of the burned limestone yielded, among other things, a brass button and a trigger guard fragment similar to items found at Fort Atkinson.[46]

Ground-penetrating radar followed by further excavation revealed a building measuring about 30 feet (9.1 m) east-west by 48 feet (15 m) north-south. The building was divided into two rooms by an interior wall, with a double fireplace in the middle. Fragments of ceramic tobacco pipes and tableware of a sort used around 1820 tended to support the conjecture that the site was actually Engineer Cantonment.[47] The quality of the items also lent support to the conjecture: while tin cups and utensils would have been used by common soldiers, the wine bottles and painted porcelain found at the site were consistent with the upper stratum of society to which the expedition's scientists belonged.[48]

Peale's drawing appeared to show two buildings, one behind the other, near the mouth of a wide ravine. In the foreground, not far from the front building, the Western Engineer and several keelboats were moored in what appeared to be an oxbow cutoff of the Missouri. Although the oxbow was no longer extant in the early 21st century, trenching east of the two-room building discovered the edge of the harbor.[49]

The search for the second building depicted by Peale was unsuccessful. Initially, it was assumed that the building already discovered was the eastern of the two, so trenches were dug to the west and southwest. These yielded no evidence of a building. The archaeologists then investigated the hypothesis that the undiscovered building was east of the known one. Excavations in that direction yielded limestone fragments and a few artifacts, but nothing that could define a building. These eastern items were buried more shallowly than the remains of the known building, and it was conjectured that the remains of the western building had been covered and protected by the alluvial fan from the ravine, while the eastern building was buried only shallowly or not at all, and its remains were effaced by exposure and erosion.[50]

Excavation continued through the 2005 season, after which the site was left open, but enclosed in a large portable building to protect it and allow further excavations. In 2011, the Missouri flooded, inundating and damaging the site; in the spring of 2015, NSHS archaeologists and students participating in the University of Nebraska–Lincoln's Archeological Field School removed silt deposited by the flood to re-expose the 2003–2005 excavations.[51]

In 2015, Engineer Cantonment was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.[1]

See also

- Fort Atkinson

- Fort Lisa

- Cabanne's Trading Post

- Winter Quarters

- History of North Omaha, Nebraska

- Landmarks in North Omaha, Nebraska

Notes

- "National Register of Historic Places Program: Weekly List: November 27, 2015". National Park Service. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- Genoways and Ratcliffe (2008), p. 3.

- Campbell (2007), pp. 20–21.

- Nichols (1971), p. 52.

- Campbell (2007), p. 21.

- Chittenden (1902), pp. 555–61.

- O'Brien (1986), pp. 2–3 of PDF.

- Carson et al. (2004), pp. 3–4 of PDF.

- Schubert (1980).

- Nichols (1971), pp. 52–54.

- Nichols (1971), p. 53.

- Nichols (1971), p. 54.

- Chittenden (1902), p. 570. The quote is from the Missouri Gazette of May 26, 1819, reproduced in Chittenden.

- Chittenden (1902), p. 571. The quote is from a contemporary letter, reproduced in Chittenden.

- Sources differ on the date of the Long party's departure from Pittsburgh. Manders and Renfro (2011), p. 11, states that the party left Pittsburgh in April 1819. Nichols (1971), p. 4 of the PDF, gives a date of May 3, 1819.

- Carlson et al. (2004), p. 5 of PDF.

- Sources differ on the date on which the Long party left St. Louis. Chittenden (1902), pp. 571–72, gives a departure date of June 9, 1819. Manders and Renfro (2011), p. 11, states that the party arrived in St. Louis on June 9 and left on June 19. Schubert (1980) gives a date of June 21 for the departure from St. Louis.

- Chittenden (1902), p. 572.

- Manders and Renfro (2011), p. 11.

- "Biography of William Baldwin". New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- Chittenden (1902), p. 569.

- Carlson et al. (2004), p. 6 of PDF.

- Chittenden (1902), p. 573.

- Sources differ on the time of the Atkinson party's arrival at the site of Camp Missouri. Chittenden (1902), p. 570, gives a date of September 26. Carlson et al. (2004), p. 6 of PDF, states that "The soldiers began arriving... in early October".

- O'Brien (1986), p. 2 of PDF.

- Carlson et al. (2004), pp. 6–7 of PDF.

- Genoways and Ratcliffe (2008), pp. 3–4.

- History of Boone County (1882), pp. 141–42.

- Carlson et al. (2004), p. 7 of PDF.

- Genoways and Ratcliffe (2008), p. 4.

- Chittenden (1902), p. 575.

- Nichols (1971), pp. 54–55.

- Carlson et al. (2004), pp. 7–8 of PDF.

- Genoways and Ratcliffe (2008), p. 22.

- Genoways and Ratcliffe (2008), p. 14.

- Genoways and Ratcliffe (2008), pp. 4–6.

- Genoways and Ratcliffe (2008), pp. 10–12.

- Genoways and Ratcliffe (2008), pp. 10–11, note that it is not always possible to tell whether a plant or animal described by the Long expedition was found at Engineer Cantonment or elsewhere. They also note that species considered new at the time of their description might no longer be regarded thus: for instance, taxonomic revision might lead to the combining of two species that were once thought distinct. New species numbers in this article are those that Genoways and Ratcliffe confirm as being from Engineer Cantonment, and that were thought to be new to science at the time of their discovery.

- "American Naturalist". American Treasures of the Library of Congress. Retrieved 2016-01-07.

- Genoways and Ratcliffe (2008), pp. 10, 14.

- Carlson et al. (2004), p. 12 of PDF.

- Genoways and Ratcliffe (2008), pp. 12–13.

- Genoways and Ratcliffe (2008), pp. 13–14, 40.

- Carlson et al. (2004), pp. 8–10 of PDF.

- Carlson et al. (2004), p. 11 of PDF.

- Carlson et al. (2004), pp. 13–16 of PDF.

- Carlson et al. (2004), pp. 16–18 of PDF.

- Rice, Melissa. "The lost is found: Engineer's Cantonment located". Washington County Pilot-Tribune & Enterprise. 2003-07-29. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- Carlson et al. (2004), pp. 13–14, 18–19 of PDF.

- Carlson et al. (2004), pp. 20–22 of PDF.

- "UNL Archeological Field School Helps Restore Engineer Cantonment Site" (2015). Nebraska History News, vol. 68, no. 3. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

References

- Campbell, Gregory (2007). "Disposession and Alienation from the Landscape". Chapter 2 of An ethnological and ethnohistorical assessment of ethnobotanical and cultural resources at the Sand Creek National Historic Site and Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site. Missoula, Montana: University of Montana. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

- Carlson, Gayle F., John R. Bozell, and Robert Pepperl (2004). The Search for Engineer Cantonment. Nebraska State Historical Society. Retrieved 2015-12-04.

- Chittenden, Hiram Martin (1902). The American Fur Trade of the Far West, vol. II. New York: Francis P. Harper. Retrieved 2016-01-04.

- Genoways, Hugh H., and Ratcliffe, Brett C. (2008). "Engineer Cantonment, Missouri Territory, 1819–1820: America's First Biodiversity Ineventory". Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences. Paper 927. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

- History of Boone County, Missouri (1882). St. Louis: Western Historical Company. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- Manders, Damon, and Brian Renfro (2011). Engineers Far from Ordinary: The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in St. Louis. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved 2016-01-04.

- Nichols, Roger L. (1971). "Stephen Long and Scientific Exploration on the Plains". Nebraska History 52:50–64. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

- O'Brien, William Patrick (1986). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory--Nomination Form: Fort Atkinson". National Park Service. Retrieved 2016-01-04.

- Schubert, Frank N. (1980). "Across the Father of Waters". Chapter 1 of Vanguard of Expansion: Army Engineers in the Trans-Mississippi West, 1819–1879. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Engineer Cantonment (Washington County, Nebraska). |