Electrical contacts

An electrical contact is an electrical circuit component found in electrical switches, relays, connectors and circuit breakers.[1] Each contact is a piece of electrically conductive material, typically metal. When a pair of contacts touch, they can pass an electrical current with a certain contact resistance, dependent on surface structure, surface chemistry and contact time;[2] when the pair is separated by an insulating gap, then the pair does not pass a current. When the contacts touch, the switch is closed; when the contacts are separated, the switch is open. The gap must be an insulating medium, such as air, vacuum, oil, SF6. Contacts may be operated by humans in push-buttons and switches, by mechanical pressure in sensors or machine cams, and electromechanically in relays. The surfaces where contacts touch are usually composed of metals such as silver or gold alloys[3][4] that have high electrical conductivity, wear resistance, oxidation resistance and other properties.[5]

Contact states

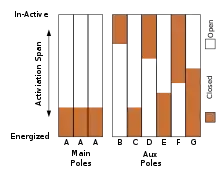

A normally closed (NC) contact pair is closed (in a conductive state) when it, or the device operating it, is in a deenergized state or relaxed state.

A normally open (NO) contact pair is open (in a non-conductive state) when it, or the device operating it, is in a deenergized state or relaxed state.

Contact form

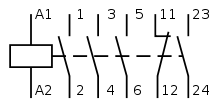

The National Association of Relay Manufacturers and its successor, the Relay and Switch Industry Association define 23 distinct forms of electrical contact found in relays and switches.[6] Of these contact forms, the following are particularly common:

Form A contacts

Form A contacts ("make contacts") are normally open contacts. The contacts are open when the energizing force (magnet or relay solenoid) is not present. When the energizing force is present, the contact will close. An alternate notation for Form A is SPST-NO.[6]

Form B contacts

Form B contacts ("break contacts") are normally closed contacts. Its operation is logically inverted from Form A. An alternate notation for Form B is SPST-NC.[6]

Form C contacts

Form C contacts ("change over" or "transfer" contacts) are composed of a normally closed contact pair and a normally open contact pair that are operated by the same device; there is a common electrical connection between a contact of each pair that results in only three connection terminals. These terminals are usually labelled as normally open, common, and normally closed (NO-C-NC). An alternate notation for Form C is SPDT.[6]

These contacts are quite frequently found in electrical switches and relays as the common contact element provides a mechanically economical method of providing a higher contact count.[6]

Form D contacts

Form D contacts ("continuity transfer" contacts) differ from Form C in only one regard, the make-break order during transition. Where Form C guarantees that, briefly, both connections are open, Form D guarantees that, briefly, all three terminals will be connected. This is a relatively uncommon configuration.[6]

Form K contacts

Form K contacts (center-off) differ from Form C in that there is a center-off or normally-open position where neither connection is made. SPDT toggle switches with a center off position are common, but relays with this configuration are relatively rare.[6]

Form X contacts

Form X or double-make contacts are equivalent to two Form A contacts in series, mechanically linked and operated by a single actuator, and can also be described as SPST-NO contacts. These are commonly found in contactors and in toggle switches designed to handle high power inductive loads.[6]

Form Y contacts

Form Y or double-break contacts are equivalent to two Form B contacts in series, mechanically linked and operated by a single actuator, and can also be described as SPST-NC contacts.[6]

Form Z contacts

Form Z or double-make double-break contacts are comparable to Form C contacts, but they almost always have four external connections, two for the normally open path and two for the normally closed path. As with forms X and Y, both current paths involve two contacts in series, mechanically linked and operated by a single actuator. Again, this is also described as an SPDT contact.[6]

Make break order

Where a switch contains both normally open (NO) and normally closed (NC) contacts, the order in which they make and break may be significant. In most cases, the rule is break-before-make or B-B-M; that is, the NO and NC contacts are never simultaneously closed during the transition between states. This is not always the case, Form C contacts follow this rule, while the otherwise equivalent Form D contacts follow the opposite rule, make before break. The less common configuration, when the NO and NC contacts are simultaneously closed during the transition, is make-before-break or M-B-B.

Electrical ratings

Contacts are rated for the current carrying capacity while closed and the voltage breaking capacity when opening (due to arcing) or while open. Opening voltage rating may be an A.C. voltage rating, D.C. voltage rating or both.[7]

Arc snuffing

When relay contacts open to interrupt a high current with an inductive load, a voltage spike will result, striking an arc across the contacts. If the voltage is high enough, an arc may be struck even without an inductive load. Regardless of how the arc forms, it will persist until the current through the arc falls to the point too low to sustain it. Arcing damages the electrical contacts, and a sustained arc may prevent the open contacts from removing power from the system being controlled.[8]

In AC systems, where the current passes through zero twice for each cycle, all but the most energetic arcs are extinguished at the zero crossing. The problem is more severe with DC where such zero crossings do not occur. This is why contacts rated for one voltage for switching AC frequently have a lower voltage rating for DC.[9]

Materials

Contacts can be produced from a wide variety of materials. Typical materials include:[5]

Electrical contact theory

Ragnar Holm contributed greatly to electrical contact theory and application.[11]

Macroscopically smooth and clean surfaces are microscopically rough and, in air, contaminated with oxides, adsorbed water vapor, and atmospheric contaminants. When two metal electrical contacts touch, the actual metal-to-metal contact area is small compared to the total contact-to-contact area physically touching. In electrical contact theory, the relatively small area where electrical current flows between two contacts is called the a-spot where "a" stands for asperity. If the small a-spot is treated as a circular area and the resistivity of the metal is homogeneous, then the current and voltage in the metal conductor has spherical symmetry and a simple calculation can relate the size of the a-spot to the resistance of the electrical contact interface. If there is metal-to-metal contact between electrical contacts, then the electrical contact resistance, or ECR (as opposed to the bulk resistance of the contact metal) is mostly due to constriction of the current through a very small area, the a-spot. For contact spots of radii smaller than the mean free path of electrons , ballistic conduction of electrons occurs, resulting in a phenomenon known also as Sharvin resistance.[12] Contact force or pressure increases the size of the a-spot which decreases the constriction resistance and the electrical contact resistance.[13] When the size of contacting asperities becomes larger than the mean free path of electrons, Holm-type contacts become the dominant transport mechanism, resulting in a relatively low contact resistance.[2]

References

- http://www.galco.com/comp/prod/relay.htm

- Zhai, C.; Hanaor, D.; Proust, G.; Gan, Y. (2015). "Stress-Dependent Electrical Contact Resistance at Fractal Rough Surfaces" (PDF). Journal of Engineering Mechanics. 143 (3): B4015001. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)EM.1943-7889.0000967.

- Matsushita Electronics, "Relay Techninal Information: Definition of Relay Terminology", § Contact, http://media.digikey.com/pdf/other%20related%20documents/panasonic%20other%20doc/small%20signal%20relay%20techincal%20info.pdf

- "Mech Eng Term" (PDF). Panasonic.biz.

- "Electrical Contact Materials". PEP Brainin. 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- Section 1.6, Engineers' Relay Handbook, 5th ed, Relay and Switch Industry Association, Arlington, VA; 3rd ed, National Association of Relay Manufacturers, Elkhart Ind., 1980; 2nd Ed. Hayden, New York, 1966; large parts of the 5th edition are on line here Archived 2017-07-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Potter Brumfield kuep-11d15-24". Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- "Contact Arc Phenomenon" (PDF). PickerComponents.com. Picker Components.

- Chapter 4, Volume IV, Lessons in Electric Circuits, EETech Media, retrieved June 2017.

- Beurskens, Jack. "Contacts - Shin-Etsu Polymer Europe B.V." www.shinetsu.info. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- "IEEE Holm Conferences on Electrical Contacts". ieee-holm.org. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- Zhai, C; et al. (2016). "Interfacial electro-mechanical behaviour at rough surfaces" (PDF). Extreme Mechanics Letters. 9: 422–429. doi:10.1016/j.eml.2016.03.021.

- Holm, Ragnar (1999). Electric Contacts: Theory and Applications (4th ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3540038757.

Further reading

- Pitney, Kenneth E. (2014) [1973]. Ney Contact Manual - Electrical Contacts for Low Energy Uses (reprint of 1st ed.). Deringer-Ney, originally JM Ney Co. ASIN B0006CB8BC. (NB. Free download after registration.)

- Slade, Paul G. (2014-02-12) [1999]. Electrical Contacts: Principles and Applications. Electrical and Computer Engineering. Electrical engineering and electronics. 105 (2 ed.). CRC Press, Taylor & Francis, Inc. ISBN 978-1-43988130-9.

- Holm, Ragnar; Holm, Else (2013-06-29) [1967]. Williamson, J. B. P. (ed.). Electric Contacts: Theory and Application (reprint of 4th revised ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-03875-7. (NB. A rewrite of the earlier "Electric Contacts Handbook".)

- Holm, Ragnar; Holm, Else (1958). Electric Contacts Handbook (3rd completely rewritten ed.). Berlin / Göttingen / Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-66223790-8. (NB. A rewrite and translation of the earlier "Die technische Physik der elektrischen Kontakte" (1941) in German language, which is available as reprint under ISBN 978-3-662-42222-9.)

- Huck, Manfred; Walczuk, Eugeniucz; Buresch, Isabell; Weiser, Josef; Borchert, Lothar; Faber, Manfred; Bahrs, Willy; Saeger, Karl E.; Imm, Reinhard; Behrens, Volker; Heber, Jochen; Großmann, Hermann; Streuli, Max; Schuler, Peter; Heinzel, Helmut; Harmsen, Ulf; Györy, Imre; Ganz, Joachim; Horn, Jochen; Kaspar, Franz; Lindmayer, Manfred; Berger, Frank; Baujan, Guenter; Kriechel, Ralph; Wolf, Johann; Schreiner, Günter; Schröther, Gerhard; Maute, Uwe; Linnemann, Hartmut; Thar, Ralph; Möller, Wolfgang; Rieder, Werner; Kaminski, Jan; Popa, Heinz-Erich; Schneider, Karl-Heinz; Bolz, Jakob; Vermij, L.; Mayer, Ursula (2016) [1984]. Vinaricky, Eduard; Schröder, Karl-Heinz; Weiser, Josef; Keil, Albert; Merl, Wilhelm A.; Meyer, Carl-Ludwig (eds.). Elektrische Kontakte, Werkstoffe und Anwendungen: Grundlagen, Technologien, Prüfverfahren (in German) (3 ed.). Berlin / Heidelberg / New York / Tokyo: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-642-45426-4.