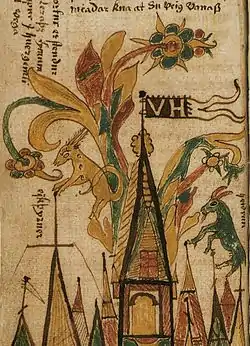

Eikþyrnir

Eikþyrnir (Old Norse "oak-thorny"[1]), or Eikthyrnir, is a stag which stands upon Valhalla in Norse mythology. The following is related in the Gylfaginning section of Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda after the description of Heiðrún.

|

Enn er meira mark at of hjörtinn Eirþyrni, [sic][2] er stendr á Valhöll ok bítr af limum þess trés, en af hornum <hans> verðr svá mikill dropi at niðr kemr í Hvergelmi, en þaðan af falla ár þær er svá heita: Síð, Víð, Sekin, Ekin, Svöl, Gunnþró, Fjörm, Fimbulþul, Gipul, Göpul, Gömul, Geirvimul, þessar falla um ásabygðir. Þessar eru enn nefndar: Þyn, Vin, Þöll, Böll, Gráð, Gunnþráin, Nyt, Nöt, Nönn, Hrönn, Vína, Veg, Svinn, Þjóðnuma. — (ch. 39; Normalized text of the R manuscript) |

Even more worthy of note is the hart Eikthyrni, which stands in Valhall and bites from the limbs of the tree; and from his horns distils such abundant exudation that it comes down into Hvergelmir, and from thence fall those rivers called thus: Síd, Víd, Søkin, Eikin, Svöl, Gunnthrá, Fjörm, Fimbulthul, Gípul, Göpul, Gömul, Geirvimul. Those fall about the abodes of the Æsir; these also are recorded: Thyn, Vín, Thöll, Höll, Grád, Gunnthráin, Nyt, Nöt, Nönn, Hrönn, Vína, Vegsvinn, Thjódnuma. — Brodeur's translation |

Brodeur follows the text of the T manuscript of the Prose Edda in putting the stag í Valhöll, "in Valhall", rather than á Valhöll, "upon Valhall", as the other manuscripts do. The more recent translation by Anthony Faulkes puts the stag on top of the building, which seems much more natural from the context and weight of the evidence.

Snorri's source for this information was almost certainly Grímnismál, where the following strophes are found.

|

|

Etymology

The etymology of Eikþyrnir remains debatable. Anatoly Liberman suggests that Heiðþyrnir, the name of the lowest heaven in Scandinavian mythology (from heið "bright sky"), was cut into two, and on the basis of those halves the names of the heavenly stag Eikþyrnir and the heavenly goat Heiðrún were formed. The origin of -þyrnir is not entirety clear, but the associations with thorns is, most probably, due to folk etymology.[3]

Notes

- Orchard (1997:36).

- variants: Eirþyrni [R], Eikþyrni [W], Eikþyrra [T], Takþyrni [U]

- Liberman (2016:345–346).

References

- Brodeur, Arthur Gilchrist (transl.) (1916). The Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson. New York: The American-Scandinavian Foundation. Available online at Google Books.

- Eysteinn Björnsson (ed.). Snorra-Edda: Formáli & Gylfaginning : Textar fjögurra meginhandrita. 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/20080611212105/http://www.hi.is/~eybjorn/gg/

- Faulkes' translation of the Prose Edda.

- Helgason, Jón. (ed.) (1955). Eddadigte (3 vols). København: Munksgaard. Text of Grímnismál available online at: http://www.snerpa.is/net/kvaedi/grimnir.htm

- Liberman, Anatoly (2016). In Prayer and Laughter. Essays on Medieval Scandinavian and Germanic Mythology, Literature, and Culture. Paleograph Press. ISBN 9785895260272.

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-34520-2

- Thorpe, Benjamin (tr.) (1866). Edda Sæmundar Hinns Froða : The Edda Of Sæmund The Learned. (2 vols.) London: Trübner & Co.