Economics of English Mining in the Middle Ages

The Economics of English Mining in the Middle Ages is the economic history of English mining from the Norman invasion in 1066, to the death of Henry VII in 1509. England's economy was fundamentally agricultural throughout the period, but the mining of iron, tin, lead and silver, and later coal, played an important part within the English medieval economy.

Invasion and the early Norman period (1066–1100)

William the Conqueror invaded England in 1066, defeating the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings and placing the country under Norman rule. This campaign was followed by fierce military operations known as the Harrying of the North between 1069 and 1070, extending Norman authority across the north of England. William's system of government was broadly feudal in that the right to possess land was linked to service to the king, but in many other ways the invasion did little to alter the nature of the English economy and mining enterprises.[1]

Mid-medieval growth (1100–1290)

Mining did not make up a large part of the English medieval economy, but the 12th and 13th centuries saw an increased demand for metals in England, thanks to the considerable population growth and building construction, including the great cathedrals and churches.[2] Four metals were mined commercially in England during the period: iron, tin, lead and silver using a variety of refining techniques.[3] Coal was also mined from the 13th century onwards,

Iron mining occurred in several locations including the main English center in the Forest of Dean, as well as in Durham and the Weald.[4] Some iron to meet English demand was also imported from the continent, especially by the late 13th century.[5] By end of the 12th century, the older method of acquiring iron ore through strip mining was being supplemented by more advanced techniques, including tunnels, trenches and bell-pits.[5] Iron ore was usually locally processed at a bloomery and by the 14th century the first water-powered iron forge in England was built at Chingley.[6] As a result of the diminishing woodlands and consequent increases in the cost of both wood and charcoal, demand for coal increased in the 12th century and began to be commercially produced from bell-pits and strip mining.[7]

A silver boom occurred in England after the discovery of silver near Carlisle in 1133. Huge quantities of silver were produced from a semicircle of mines reaching across Cumberland, Durham and Northumberland - up to three to four tonnes of silver were mined each year, more than ten times the previous annual production across the whole of Europe.[8] The result was a local economic boom and a major uplift to 12th century royal finances.[9] Tin mining was centred in Cornwall and Devon, exploiting alluvial deposits and governed by the special Stannary Courts and Parliaments - tin formed a valuable export good, initially to Germany and then later in the 14th century to the Low Countries.[10] Lead was usually mined as a by-product of mining for silver, with mines in Yorkshire, Durham and the north, as well as in Devon.[11] Economically fragile, the lead mines usually survived as a result of being subsidised by silver production.[12]

Mid-medieval economic crisis - the Great Famine and the Black Death (1290–1350)

Great Famine

The Great Famine of 1315 began a number of acute crises in the English agrarian economy. The famine centered on a sequence of harvest failures in 1315, 1316 and 1321, combined with an outbreak of the murrain sickness amongst sheep and oxen between 1319 and 1321 and the fatal ergotism fungi amongst the remaining stocks of wheat.[13] In the ensuing famine, many people died and the peasantry were said to have been forced to eat horses, dogs and cats as well to have conducted cannibalism against children, although these last reports are usually considered to be exaggerations.[14] The Great Famine firmly reversed the population growth of the 12th and 13th centuries and left a domestic economy that was "profoundly shaken, but not destroyed".[15]

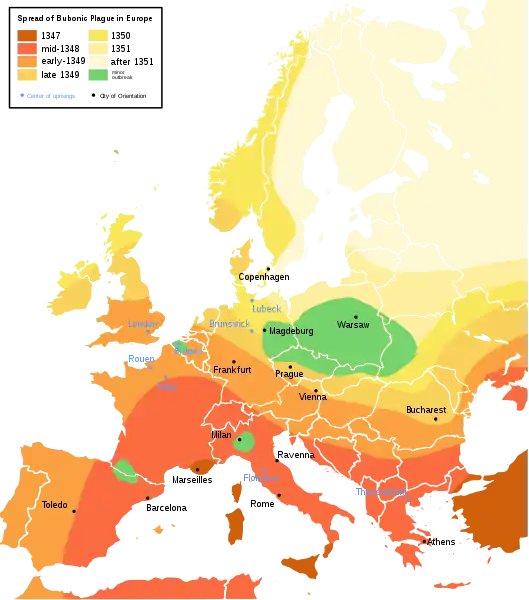

Black Death

The Black Death epidemic first arrived in England in 1348, re-occurring in waves during 1360-2, 1368-9, 1375 and more sporadically thereafter.[16] The most immediate economic impact of this disaster was the widespread loss of life, between around 27% mortality amongst the upper classes, to 40-70% amongst the peasantry.[17][nb 1] Despite the very high loss of life, few settlements were abandoned during the epidemic itself, but many were badly affected or nearly eliminated altogether.[18] The medieval authorities did their best to respond in an organised fashion, but the economic disruption was immense.[19] Building work ceased and many mining operations paused.[20] In the short term, efforts were taken by the authorities to control wages and enforce pre-epidemic working conditions.[21] Coming on top of the previous years of famine, however, the longer term economic implications were profound.[21] In contrast to the previous centuries of rapid growth, the English population would not begin to recover for over a century, despite the many positive reasons for a resurgence.[22] The crisis would affect English mining for the remainder of the medieval period.[23]

Late medieval economic recovery (1350–1509)

Mining generally performed well at the end of the medieval period, helped by buoyant demand for manufactured and luxury goods. Cornish tin production plunged during the Black Death itself, leading to a doubling of prices.[24] Tin exports also collapsed catastrophically, but picked up again over the next few years.[25] By the turn of the 16th century, the available alluvial tin deposits in Cornwall and Devon had begun to decline, leading to the commencement of bell and surface mining to support the tin boom that occurred in the late 15th century.[26] Lead mining increased, with output almost doubling between 1300 and 1500.[26] Wood and charcoal became cheaper once again after the Black Death, and coal production declined as a result, remaining depressed for the rest of the period - nonetheless, some coal production was occurring in all the major English coalfields by the 16th century.[27] Iron production continued to increase; the Weald in the South-East began to make increased use of water-power, and overtook the Forest of Dean in the 15th century as England's main iron-producing region.[27] The first blast furnace in England, a major technical step forward in metal smelting, was created in 1496 in Newbridge in the Weald.[28]

Notes

- The precise mortality figures for the Black Death have been debated at length for many years.

References

- Dyer 2009, p.8.

- Hodgett, p.158; Barnes, p.245.

- Homer, p.57; Bayley pp131-2.

- Geddes, p.169; Bailey, p.54.

- Geddes, p.169.

- Geddes, p.169, 172.

- Bailey, p.52.

- Blanchard, p.29.

- Blanchard, p.33.

- Homer, p.57, pp61-2; Bailey, p.55.

- Homer, p57, p.62.

- Homer, p.62.

- Cantor 1982a, p.20; Aberth, p.14.

- Aberth, pp13-4.

- Jordan, p.78; Hodgett, p.201.

- Dyer 2009, p.271, 274; Hatcher 1996, p.37.

- Dyer 2009, p.272, Hatcher 1996, p.25.

- Dyer 2009, p.274.

- Dyer 2009, pp272-3.

- Dyer 2009, p.273.

- Fryde and Fryde, p.753.

- Hatcher 1996, p.61.

- Dyer 2009, p.278.

- Homer, p.58.

- Hatcher 1996, p.40.

- Bailey, p.55.

- Bailey, p.54.

- Geddes, p.174.

Bibliography

- Aberth, John. (2001) From the Brink of the Apocalypse: Confronting Famine, War, Plague and Death in the Later Middle Ages. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92715-3.

- Anderson, Michael. (ed) (1996) British Population History: From the Black Death to the Present Day. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57884-4.

- Barnes, Carl F. (2005) "A Note on Villard de Honnecourt and Metal," in Bork (ed) 2005.

- Bailey, Mark. (1996) "Population and Economic Resources," in Given-Wilson (ed) 1996.

- Bayley, J. (2009) "Medieval Precious Metal Refining: Archaeology and Contemporary Texts Compared," in Martinon-Torres and Rehren (eds) 2009.

- Blair, John and Nigel Ramsay. (eds) (2001) English Medieval Industries: Craftsmen, Techniques, Products. London: Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-1-85285-326-6.

- Blanchard, Ian. (2002) "Lothian and Beyond: the Economy of the "English Empire" of David I," in Britnell and Hatcher (eds) 2002.

- Bork, Robert Odell. (ed) (2005) De Re Metallica: The Uses of Metal in the Middle Ages. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-5048-5.

- Britnell, Richard and John Hatcher (eds). (2002) Progress and Problems in Medieval England: Essays in Honour of Edward Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52273-1.

- Cantor, Leonard (ed). (1982) The English Medieval Landscape. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 978-0-7099-0707-7.

- Cantor, Leonard. (1982a) "Introduction: the English Medieval Landscape," in Cantor (ed) 1982.

- Dyer, Christopher. (2009) Making a Living in the Middle Ages: The People of Britain, 850 - 1520. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10191-1.

- Fryde, E. B. and Natalie Fryde. (1991) "Peasant Rebellion and Peasant Discontents," in Miller (ed) 1991.

- Geddes, Jane. (2001) "Iron," in Blair and Ramsay (eds) 2001.

- Given-Wilson, Chris (ed). (1996) An Illustrated History of Late Medieval England. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4152-5.

- Hatcher, John. (1996) "Plague, Population and the English Economy," in Anderson (ed) 1996.

- Hodgett, Gerald. (2006) A Social and Economic History of Medieval Europe. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-37707-2.

- Homer, Ronald F. (2010) "Tin, Lead and Pewter," in Blair and Ramsay (eds) 2001.

- Jordan, William Chester. (1997) The Great Famine: Northern Europe in the Early Fourteenth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05891-7.

- Miller, Edward. (ed) (1991) The Agrarian History of England and Wales, Volume III: 1348-1500. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20074-5.