Dunbrody Abbey

Dunbrody Abbey (Irish: Mainistir Dhún Bróithe) is a former Cistercian monastery in County Wexford, Ireland.[1][2][3] The cross-shaped church was built in the 13th century, and the tower was added in the 15th century. With a length of 59m the church is one of the longest in Ireland. The visitor centre is run by the current Marquess of Donegall and has one of only two full sized hedge mazes in Ireland.

South-east view of the living quarters, the tower, and the choir | |

Location within Ireland | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Cistercians |

| Established | 1182 |

| Disestablished | 1536 |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Hervey de Monte Marisco, Marshal of our Lord the King in Ireland and Senechal of Richard de Clare, Second Earl of Pembroke (Strongbow) |

| Architecture | |

| Status | Ruin |

| Site | |

| Location | Dunbrody, County Wexford, Ireland |

| Public access | Yes |

| Official name | Dunbrody Abbey |

| Reference no. | 192 |

The abbey was dissolved under Henry VIII. The last Abbot of Dunbrody was Alexander Devereux, who became Bishop of Ferns in 1539.

History

In 1169 a contingent of Norman knights led by the King of Leinster, Dermot MacMurrough, invaded Ireland, first conquering the Irish province of Leinster then all of Ireland. In 1171 Henry II led a much larger force into Ireland, taking control and making Ireland a territory of England. Richard de Clare, one of the important figures in the Norman Conquest, instructed his uncle Herve de Montmorency to found a Cistercian monastery in the County Wexford.[4] Montmorency donated the allotted land to the English Cistercian Abbey of Buildwas. The Abbey of Buildwas sent a lay brother to survey the land and, after an unfavorable report, Buildwas turned down the gift. The property was then offered to St. Mary’s Cistercian Abbey in Dublin, which was in the filial line of Clairvaux.[4] The monks of St. Mary’s were delighted with their new land and they soon sent a community to the site in 1182. Due to its position near a major maritime transportation route, the abbey was placed under the patronage of the Blessed Virgin Mary, with the name Port of St. Mary’s, because of the safety the abbey offered to people in trouble.

The middle of the 13th century was a boom period for the Anglo-Norman colony in Ireland and the Cistercian order shared in this prosperity. The scale and quality of the 13th century buildings constructed at Dunbrody gives a general hint of confidence and well being. The spacious early Gothic church was built sometime around 1210–1240 for the monks of Dunbrody Abbey. Dunbrody, though a relatively small abbey, was very successful until the 16th century and the rise of King Henry VIII. Following his split with the Church of Rome, Henry VIII issued the Dissolution of the Monasteries through a series of administrative and legal processes between 1536 and 1541. Dunbrody was part of the first round of suppressions in Ireland and was officially dissolved in 1536. The abbey was plundered and made unfit for monks to return. The lead from the roof was melted down by using the wood from the roof. Nine years later, Sir Osborne Echyngham was given the land and the monastery which he converted into a residence. Owing to the neglect of the private owners of Dunbrody, a massive collapse occurred on Christmas Eve 1852, destroying the south wall of the church and some of the monastery. The abbey lies in ruins until this day.

Architecture

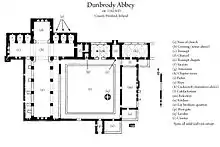

The church is in the form of a cross on plan, as is usual in Cistercian Abbeys, and has a nave, side aisles, north and south transepts, and choir. Apartments were formed in the roof over the chapels in the transepts (each transept has three chapels), one over the north transept (left transept on the plan) was approached by the circular stairs and a passage across the triforium of the north transept. There is also evidence of a floor having at one time been carried over the whole of the north transept. The space over the side chapels of the south transept contained a fireplace and five windows, and over it another floor, probably divided into two apartments, as it contains two fireplaces and has also five windows.[5]

The nave was separated from the aisles by an arcade of five bays. In the north aisle are four large buttresses; it is entirely owing to these buttresses that this wall is preserved. The south arcade and the wall of the south aisle fell in a storm on Christmas Eve 1852. The nave was lit by a row of clerestory windows and also three lights that formed the large west window.[5]

A very remarkable feature is shown in the construction of the bell tower. The rules of the Order did not originally permit the erection of a tower, but this prohibition was later removed. In many other similar structures the original transept arches have been used to carry the walls of a tower, however in this case the old arches were not built upon, but new piers were built alongside the old, and new arches were formed at the nave and choir, and in this way the stability of the tower was secured. There were seven bells in the tower plan, indicated by the seven openings for the bell ropes to the ringing chamber through the vault carrying the floor of the tower. There was also a large opening square through which the bells were hoisted.[5]

The range of buildings east of the cloister garth and south of the church comprises the sacristy and an inner room opening off it. There is here a small apartment with a door giving access from the cloister walk. This apartment, which is usually found in monasteries of this Order, is sometimes described as a prison, but is more likely to have been the book store, a convenient place for keeping books to read in the cloisters. There were several more apartments southwards including the parlour and chapter room, and over the whole of this range the dormitories extended, approached by the night stairs in the south transept, and at the other end by the stairs in the passage at the south-east angle of the cloister enclosure.[5]

In the southern range of buildings there is evidence of the position of the refectory by the indication of the reader's desk at one of the windows in south side wall. Although this range is not now divided by cross walls, it is likely that the eastern end was occupied by the calefactory, or warming house, and the western end by the butteries and kitchen. Excavation in the cloister garth has revealed the foundations of the lavabo, occupying the usual position near the door of the refectory.[5]

Gallery

View from South-east

View from South-east Nave, south aisle and base of bell tower

Nave, south aisle and base of bell tower North arcade showing three of the four large buttresses that have preserved the wall

North arcade showing three of the four large buttresses that have preserved the wall Buildings east of cloister garth

Buildings east of cloister garth Underside of the floor of bell tower

Underside of the floor of bell tower Foundations of lavabo

Foundations of lavabo

See also

- List of abbeys and priories in Ireland (County Wexford)

References

- J.T. Gilbert (ed.), Chartularies of St Mary's Abbey, Dublin, with the Register of its House at Dunbrody, and Annals of Ireland, 2 vols, Rolls Series, Rerum Britannicarum Medii Aevi Scriptores LXXX (Longman & Co., London 1884), II, pp. lxvii-c (Internet Archive).

- J. Morrin, 'Historical notes of the Abbey of Dunbrodin', Transactions of the Ossory Archaeological Society, I: 1874-1879 (1879), pp. 407-31 (Internet Archive).

- B. Colfer, The Hook Peninsula: County Wexford, Irish Rural Landscapes: II (Cork University Press 2004), pp. 61-68 (Google).

- Leroux-Dhuys, Jean-François. Cistercian Abbeys. Konemann, 1998. P178

- Extract of Historical and Descriptive Notes Of Dunbrody Abbey, 1910

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dunbrody Abbey. |

- Dunbrody Abbey (Official Site)