Dream Cave

Dream Cave (sometimes called Dream Hole or Dream Mine) is a natural limestone cavern located near Wirksworth in Derbyshire, England. It was discovered by lead miners in 1822 and was found to contain the almost complete skeletal remains of a woolly rhinoceros and other large mammal bones. These remains were acquired by the geologist William Buckland and are now housed in Oxford Museum.[2]

| Dream Cave | |

|---|---|

| Dream Hole, Dream Mine | |

| |

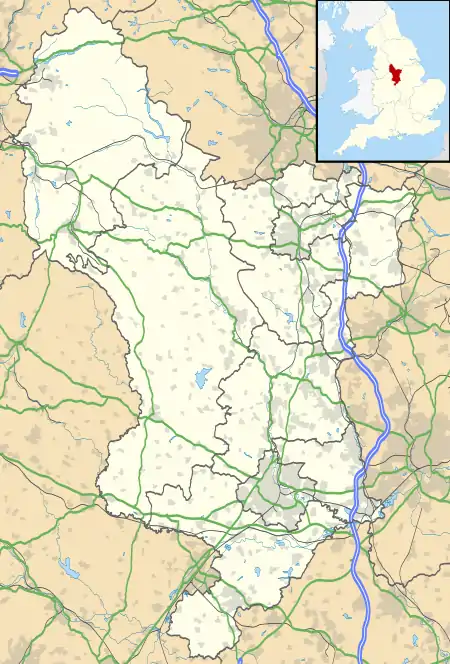

| Location | Derbyshire, England |

| OS grid | SK275530 |

| Coordinates | [1] |

| Depth | 15m |

| Elevation | 240m |

| Discovery | 1822 |

| Geology | Carboniferous limestone |

| Difficulty | 1 |

| Access | private |

| Features | Quaternary megafauna |

| Cave survey | 1823; 2016 (in COMPASS) |

Location and description

Dream Cave formed as a natural karstic cavity along a vein of mineralisation within a series of Lower Carboniferous limestone rocks called the Monsal Dale Formation.[3] The entrance to Dream Cave (known to cavers as Dream Hole) is on a grass-covered mound, on a hillside to the west of the town of Wirksworth, east of Carsington Reservoir, and overlooking woodland. This entrance is a deep and steep-sided natural fissure within the limestone, and is in fields pockmarked by former lead-mining activity.[1][2] Dream Cave lies at an altitude of approximately 240 metres (790 ft) and is about 15 metres (49 ft) deep,[1] with cavities running in a west-north-west to east-south-easterly direction. Although originally completely infilled with loose material, almost all has since been removed, and what little remains is so disturbed that it shows none of the original stratigraphy.[3]:110

Discovery

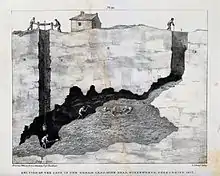

Dream Cave was discovered by lead miners in December 1822, during work to sink a new shaft 60 feet (18 m) down into a hillside above Wirksworth to reach productive veins of lead ore within Dream Mine. In doing so, the miners unexpectedly penetrated a large natural cavern within the hillside which had become completely infilled with a loose material of argillaceous earth and rock fragments. According to a detailed contemporary account, as they excavated this material to continue their downward progress, the loose infill began to shift and collapse around them. The act of removing this loose material eventually exposed the roof of the cave itself. Close to the centre of the collapsing mass, the miners found numerous bones and what was probably at the time a complete skeleton of a large mammal before the collapsing sediments caused the bones to separate.[4] In removing the infill, the miners had uncovered what, on expert examination, turned out to be the nearly complete skeleton of a rhinoceros.[2][5] This was subsequently confirmed to be a woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis).[6]

Initially, there was no evidence that the cavern had been connected to the surface. As the sinking of the mine shaft progressed, and as collapsing material was removed, a depression began to form in the field above. Eventually, as more collapsing infill was taken away, the connecting void that slowly opened up was found to be approximately 6 feet (1.8 m) broad and 50 feet (15 m) deep.[4]

Mammalian remains

One month later, in January 1823, the eminent Oxford geologist the Reverend William Buckland arrived to inspect the finds at Dream Cave. By this time many of the bones had been removed on the command of the landowner, Philip Gell. Buckland's detailed account of his inspection of Dream Cave and its remains was subsequently published in his Reliquiæ Diluvianæ, or, Observations on the Organic Remains attesting the Action of a Universal Deluge. He described the rhinoceros skeleton to have included a head, ten molar teeth, one complete half of the lower jaw, and damaged fragments of the other half. Two cervical vertebrae, several dorsal and two caudal vertebrae and various ribs, sacrum and pelvis were also retrieved, as well as the long bones of all four limbs. All were well preserved and from a nearly full-grown animal. No additional rhinoceros bones were found to suggest a second animal had died there, although bones from other large mammal species were also found. These included horse, ox and deer. Mr Gell subsequently donated these specimens to Oxford Museum.[4] Later research has suggested that they first entered Buckland's own private collections at Christchurch College before later being transferred to Oxford Museum after its founding in 1860.[3] By 1861 the larger bones were on display at Oxford Museum, although by 1874 some of the smaller specimens had been moved into storage.[3]

Although the whereabouts of the rhinoceros bones from Dream Cave were still remembered in the 1880s,[7] one hundred and twenty years later they had become forgotten, and believed by some to have been lost to science.[8] Thus, by the end of the 20th century, the precise species of rhinoceros found in Dream Cave was not known with certainty.[9]

21st-century research

The bones and associated material removed from Dream Cave by Buckland had not been lost, as had previously been assumed, but had remained in Oxford Museum, including specimens labelled by him as Rhinoceros tichorhinus (a synonym for the woolly rhinoceros).[3]:111 Further curation and detailed studies then began around the turn of the century. In 2000, indirect radiometric dating of flowstone material collected by Buckland, and assumed to have immediately overlain the mammalian bones gave a date of 36,450 years before present (plus/minus 1,260 years). This suggested the woolly rhinoceros and other animals had fallen into Dream Cave just over 37,000 years Before Present (BP). This correlates with Marine isotope stage 3 interstadial of the last glacial period (early Devensian).[6]

In 2016 some of the original research team resurveyed Dream Cave and also made direct radiocarbon dating of aurochs/bison bones found alongside the woolly rhinoceros. This yielded calibrated dates of 45,083 – 48,613 BP.[3] The team concluded that Buckland was correct in his original interpretation that the complete woolly rhinoceros skeleton resulted, not from a direct fall into the cavern, but by inwashing from an extreme flood event. Whereas Buckland stated this was "a carcase that was drifted in entire at the same time with the diluvial detritus"[4]:64 (i.e.Biblical flood), modern science interprets this as in-washing from a high-volume flood event, resulting from a sudden spring thaw after a cold winter period, which were typical of the glacial-period climate in that region at that time.[3]:113

Species list

The following species from Dream Cave are now housed in Oxford Museum:[3]:115–116

- Woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) – 74 bones

- Aurochs/steppe bison (Bos primigenius/Bison priscus) – material insufficient to diagnose precise species

- Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus)

- Horse (Equus sp.)

Although only large mammal remains were retrieved and retained, it is highly probable that microfaunal remains were also present, though not preserved. This reflects collection preferences at that early time, but in correspondence to Sir Everard Home, Philip Gell wrote in 1823: "The Rhinoceros appears to have occupied the centre of the Cave, the Ox and Deer one end, and the smaller animals the other end."[3]:110

Significance

The discovery of Dream Cave and its faunal remains is of historical importance as it came just as William Buckland was developing his theories and preparing to publish a major work about cave palaeontology and on the origins of extinct fossil vertebrates and their association with the Biblical flood; the cave was described in considerable detail and illustrated in his 1823 treatise, Reliquiæ Diluvianæ.[3]:109[6]

The near-complete woolly rhinoceros from Dream Cave is an unusual example of a species rarely found in the UK,[3]:113 especially as it shows no signs of having been eaten by hyaenas.[2]

Threats

In 2016 it was reported that Dream Cave had suffered from the dumping of agricultural debris and by partial in-filling. It is not protected by statutory designation as a Site of Special Scientific Interest, though by 2013 both it and surrounding areas had been formally listed on An Updated Inventory of Important Metal and Gangue Mining Sites in the Peak District.[3]:114[10]

References

- "Dream Hole – DCA Cave Registry Site Details". registry.thedca.org.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Vahed, Karim (January 2019). "The Secret of Wirksworth's Dream Cave". Derbyshire Life. Archant Community Media Ltd. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Mcfarlane, Donald A.; Lundberg, Joyce; Van Rentergem, Guy; Howlett, Eliza (December 2016). "A new radiometric date and assessment of the Last Glacial megafauna of Dream Cave, Derbyshire, UK". Cave and Karst Science. 43 (3). Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Buckland, William (1824). Reliquiae Diluvianae; Or, Observations on the Organic Remains Contained in Caves, Fissures and Diluvial Gravel, and on Other Geological Phenomena, Attesting the Action of an Universal Deluge. By the Rev. William Buckland, ... John Murray, Albemarle-street. pp. 61–67. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Jewitt, Llewellynn (1861). The reliquary; A depository for precious relics-legendary, biographical and historical, Illustrative of the habits, customs and pursuits of our forefathers: Edited by Llewellynn Jewitt. John Russell Smith. Derby: Bemrose & sons. p. 226. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Mcfarlane, Donald A.; Lundberg, Joyce; Ford, Derek C. (January 2000). "The Age of the Woolly Rhino from Dream Cave, Derbyshire, UK". Cave and Karst Science. 27 (1). Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Heath, Thomas (January 1882). "Pleistocene deposits of Derbyshire and its immediate vicinity". Journal of the Derbyshire Archaeological and Natural History Society. 4: 163. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Schreve, Danielle; et al. (25 February 2013). "A Middle Devensian woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) from Whitemoor Haye Quarry, Staffordshire (UK): palaeoenvironmental context and significance" (PDF). Journal of Quaternary Science. 28 (2): 121. Bibcode:2013JQS....28..118S. doi:10.1002/jqs.2594. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Ford, Trevor (1999). "The Growth of Geological Knowledge in the Peak District" (PDF). Mercian Geologist. 14 (4): 164. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Barnatt, J.; Huston, K.; Mallon, D.; Newman, R. (2013). "The Lead Legacy: An Updated Inventory of Important Metal and Gangue Mining Sites in the Peak District" (PDF). Mining History: The Bulletin of the Peak District Mines Historical Society. 18 (6). Retrieved 22 October 2019.

External links

Media related to Dream Cave at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dream Cave at Wikimedia Commons