Douwe Sirtema van Grovestins

Jonkheer[1] Douwe Sirtema van Grovestins (Leeuwarden, Brussels, 1710 – 26 February 1778) was a Frisian courtier at the court of stadtholder William IV, Prince of Orange, and later at the court of his widow Anne, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange. He was first Chamberlain, later Equerry to the stadtholder, and equerry to the Princess after her husband's death.

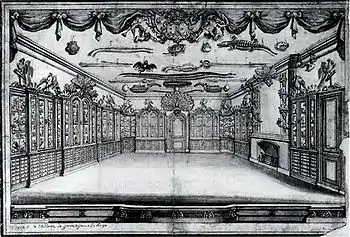

Douwe was married to Baroness Carolina Sinoldt gennant Schütz (whose curiocabinet in The Hague is shown in a picture from 1756) and had a son, Lodewijk Idzard Douwe with her in 1749.

After the stadtholder's court moved from Leeuwarden to The Hague during the Orangist Revolution of 1747 at the end of the Second Stadtholderless Period Douwe became very influential in the patronage politics of the regency of the Princess during the first years of the minority of William V, Prince of Orange. His scandalous dealings for his own profit in public offices (he sold the governorship of the Dutch East India Company colony of Ceylon in 1756 for 70,000 guilders, for instance[2]) helped put the stadtholderate in bad repute.[3] This brought about his removal from court after the death of Princess Anne in 1759. Nevertheless, he was made a lieutenant-general in the army of the Dutch Republic, and served as governor of the Barrier Fortress Ieper in the Austrian Netherlands in 1774.

Probably because he played a central role in the corrupt practices of the regime of the Stadtholderate he also was the subject of widespread rumors that he had had a liaison with Princess Anne, and even fathered the future stadtholder William V. Except for the uncanny family resemblance between himself and William, Anne's biographer Veronica Baker-Smith thinks there is insufficient ground to believe this rumour. She points out that such rumours are being flung about quite casually for political reasons, and that when a pamphlet was published in 1782, alleging William V's illegitimacy, this was in the middle of the Patriot crisis, and the author was clearly a Patriot partisan.[4]

Late in life Douwe became the protector and lover of the early feminist Etta Palm d'Aelders, whom he apparently taught the skills to set up as a high-class courtesan, and organiser of a political Salon in pre-Revolutionary Paris.

References

- His descendants were recognized as barons by the Kingdom of the Netherlands

- Oostrum, W R D Van (1999) Juliana Cornelia de Lannoy (1738-1782): ambitieus, vrijmoedig en gevat, Uitgeverij Verloren, ISBN 90-6550-057-X, p. 287

- Israel, J.I. (1995), The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness and Fall, 1477-1806, Oxford University Press,ISBN 0-19-873072-1 hardback, ISBN 0-19-820734-4 paperback, p. 1082

- Baker-Smith,V.P.M. (1995) A Life of Anne of Hanover, Princess Royal, Brill, ISBN 90-04-10198-5, pp. 140-141