Domestication syndrome

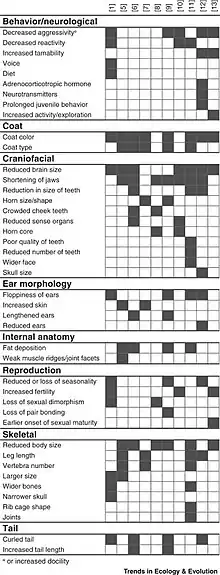

Domestication syndrome refers to a number of phenotypic traits that appear in many domesticated animals. These also appeared in the domesticated silver fox that is the result of Dmitry Belyayev's breeding experiment.[1] These traits may include floppy ears, variations to coat colour, a smaller brain, and a shorter muzzle.[1]

Origin

Charles Darwin’s study of The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication in 1868 identified behavioural, morphological, and physiological traits that are shared by domestic animals, but not by their wild ancestors. These shared traits became known as the domestication syndrome.[3] These traits include tameness, docility, floppy ears, altered tails, novel coat colours and patterns, reduced brain size, reduced body mass and smaller teeth.[3][4] Other traits include changes in craniofacial morphology, alterations to the endocrine system, and changes to the female estrous cycles including the ability to breed all year-round.[4]

Research indicates that neural crest cells may have been modified by domestication, which then led to those traits that are common across many domesticated animal species.[1]

Challenge

In 2015, canine researcher Raymond Coppinger found historical evidence that Belyayev's foxes originated in fox farms on Prince Edward Island and had been bred there for fur farming since the 1800s, and that the traits demonstrated by Belyayev had occurred in the foxes prior to the breeding experiment.[5] In 2019, a further study found that the results of the "Farm fox experiment" had been overstated, based on historical records and DNA analysis. This finding questions the existence of domestication syndrome in animals and suggests that other theories need to be considered, including adaptations to a human-modified environment.[2]

Although the soundness of the domestication syndrome, and the extent to which the Belyaev experiment could be used as evidence to support its existence, has been questioned, the hypothesis that neural crest genes underlie some of the phenotypic differences between domestic and wild horses and dogs is supported by the functional enrichment of candidate genes under selection.[1]

References

- Frantz, Laurent A. F.; Bradley, Daniel G.; Larson, Greger; Orlando, Ludovic (2020). "Animal domestication in the era of ancient genomics". Nature Reviews Genetics. 21 (8): 449–460. doi:10.1038/s41576-020-0225-0. PMID 32265525. S2CID 214809393.

- Lord, Kathryn A.; Larson, Greger; Coppinger, Raymond P.; Karlsson, Elinor K. (2020). "The History of Farm Foxes Undermines the Animal Domestication Syndrome". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 35 (2): 125–136. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2019.10.011. PMID 31810775.

- Irving-Pease, Evan K.; Ryan, Hannah; Jamieson, Alexandra; Dimopoulos, Evangelos A.; Larson, Greger; Frantz, Laurent A. F. (2018). "Paleogenomics of Animal Domestication". In Lindqvist, C.; Rajora, O. (eds.). Paleogenomics. Population Genomics. Springer, Cham. pp. 225–272. doi:10.1007/13836_2018_55. ISBN 978-3-030-04752-8.

- Machugh, David E.; Larson, Greger; Orlando, Ludovic (2016). "Taming the Past: Ancient DNA and the Study of Animal Domestication". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 5: 329–351. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-022516-022747. PMID 27813680.

- Gorman, James (2019-12-03). "Why Are These Foxes Tame? Maybe They Weren't So Wild to Begin With". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-11-18.