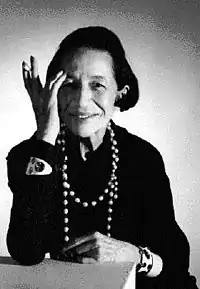

Diana Vreeland

Diana Vreeland (September 29, 1903[2] – August 22, 1989) was a French-American columnist and editor in the field of fashion. She worked for the fashion magazines Harper's Bazaar and Vogue, being the editor-in-chief of the latter, and as a special consultant at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She was named on the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame in 1964.[3][4]

Diana Vreeland | |

|---|---|

Diana Vreeland (1979) by Horst P. Horst | |

| Born | Diana Dalziel September 29, 1903 Paris, France |

| Died | August 22, 1989 (aged 85) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1936–89 |

| Employer | Hearst Corporation and Condé Nast Publications |

| Agent | Irving Paul Lazar |

| Title | Editor-in-chief of Vogue |

| Term | 1963–71 |

| Predecessor | Jessica Daves |

| Successor | Grace Mirabella |

| Spouse(s) | Thomas Reed Vreeland

(m. 1924; died 1966) |

| Children | 2, including Frederick Vreeland |

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | |

| Website | www |

Early life

Born Diana Dalziel in Paris, France at 5 avenue du Bois-de-Boulogne (Avenue Foch since World War I). Vreeland was the eldest daughter of her American socialite mother, Emily Key Hoffman (1876–1928), and British stockbroker[5] father Frederick Young Dalziel (1868–1960). Hoffman was a descendant of George Washington's brother as well as a cousin of Francis Scott Key. She also was a distant cousin of writer and socialite Pauline de Rothschild (née Potter; 1908–1976). Vreeland had one sister, Alexandra (1907–1999), who later married Sir Alexander Davenport Kinloch, 12th Baronet (1902–1982). Their daughter Emily Lucy Kinloch married Lt.-Col. Hon. Hugh Waldorf Astor (1920–1999), the second son of John Jacob Astor, 1st Baron Astor of Hever and Violet Astor, Baroness Astor of Hever.

Vreeland's family emigrated to the United States at the outbreak of World War I, and moved to 15 East 77th Street in New York, where they became prominent figures in society. Vreeland was sent to dancing school as a pupil of Michel Fokine, the only Imperial Ballet master ever to leave Russia, and later of Louis Harvy Chalif. Vreeland performed in Anna Pavlova's Gavotte at Carnegie Hall. In January 1922, Vreeland was featured in her future employer, Vogue, in a roundup of socialites and their cars. The story read, "“Such motors as these accelerate the social whirl. Miss Diana Dalziel, one of the most attractive debutantes of the winter, is shown entering her Cadillac."[6]

On March 1, 1924, Diana Dalziel married Thomas Reed Vreeland (1899–1966), a banker and international financier,[5] at St. Thomas' Church in New York, with whom she would have two sons: Tim (Thomas Reed Vreeland, Jr.) born 1925, who became an architect as well as a professor of architecture at the University of New Mexico and then UCLA, and Frecky (Frederick Dalziel Vreeland) born 1927 (later U.S. ambassador to Morocco).[7] A week before her wedding, The New York Times reported that her mother had been named co‑respondent in the divorce proceedings of Sir Charles Ross and his second wife, Patricia. The ensuing society scandal estranged Vreeland and her mother, who died in September 1928 in Nantucket, Massachusetts.

After their honeymoon, the Vreelands moved to Brewster, New York, and raised their two sons, staying there until 1929. They then moved to 17 Hanover Terrace, Regent's Park, London, previously the home of Wilkie Collins and Edmund Gosse. During her time in London, she danced with the Tiller Girls and met Cecil Beaton, who became a lifelong friend. Like Syrie Maugham and Elsie de Wolfe, other society women who ran their own boutiques, Diana operated a lingerie business near Berkeley Square. Her clients included Wallis Simpson and Mona Williams. She often visited Paris, where she would buy her clothes, mostly from Chanel, whom she had met in 1926. She was one of fifteen American women presented to King George V and Queen Mary at Buckingham Palace on May 18, 1933.[8] In 1935, her husband's job brought them back to New York, where they lived for the remainder of their lives.

Vreeland stated, "Before I went to work for Harper's Bazaar in 1936, I had been leading a wonderful life in Europe. That meant traveling, seeing beautiful places, having marvelous summers, studying and reading a great deal of the time."[9]

A biographical documentary of Vreeland, The Eye has to Travel,[10] debuted in September 2012 at the Angelika Theater in New York City.

Career

Harper's Bazaar 1936–1962

Her publishing career began in 1936 as columnist for Harper's Bazaar. Carmel Snow, the editor of Harper's Bazaar, was impressed with Vreeland's clothing style and asked her to work at the magazine.[11] From 1936 until her resignation, Diana Vreeland ran a column for Harper's Bazaar called "Why Don't You?". One example is a suggestion she made in the column, "Why don't you...Turn your child into an Infanta for a fancy-dress party?"[12] According to Vreeland, "The one that seemed to cause the most attention was [...] "[Why Don't You] [w]ash your blond child's hair in dead champagne, as they do in France." Vreeland says that S. J. Perelman wrote a parody of it for The New Yorker magazine that outraged her then-editor Carmel Snow.[13]

Diana Vreeland "discovered" actress Lauren Bacall during World War II. The Harper's Bazaar cover for March 1943[14] shows Lauren Bacall posing near a Red Cross office, based on Vreeland's decision: "[T]here is an extraordinary photograph in which Bacall is leaning against the outside door of a Red Cross blood donor room. She wears a chic suit, gloves, a cloche hat with long waves of hair falling from it".[15] Vreeland was noted for taking fashion seriously. She commented in 1946 that "[T]he bikini is the most important thing since the atom bomb".[16] Vreeland disliked the common approach to dressing that she saw in the United States in the 1940s. She detested "strappy high-heel shoes" and the "crêpe de chine dresses" that women wore even in the heat of the summer in the country.[17]

Until her resignation at Harper's Bazaar, she worked closely with Louise Dahl-Wolfe,[18] Richard Avedon, Nancy White,[19] and Alexey Brodovitch. Diana Vreeland became Fashion Editor for the magazine. Richard Avedon said when he first met Diana Vreeland and worked for Harper's Bazaar, "Vreeland returned to her desk, looked up at me for the first time and said, 'Aberdeen, Aberdeen, doesn't it make you want to cry?' Well, it did. I went back to Carmel Snow and said, 'I can't work with that woman. She calls me Aberdeen.' And Carmel Snow said, 'You're going to work with her.' And I did, to my enormous benefit, for almost 40 years."[20] Avedon said at the time of her death that "she was and remains the only genius fashion editor".[21]

In 1955, the Vreelands moved to a new apartment which was decorated exclusively in red. Diana Vreeland had Billy Baldwin (1903–1983) decorate her apartment.[22] She said, "I want this place to look like a garden, but a garden in hell".[20] Regular attendees at the parties the Vreelands threw were socialite C. Z. Guest, composer Cole Porter, and British photographer Cecil Beaton.[20] Paramount's 1957 movie musical Funny Face featured a character—Maggie Prescott as portrayed by Kay Thompson—based on Vreeland.[23]

In 1960, John F. Kennedy became president and Diana Vreeland advised the First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy in matters of style. "Vreeland advised Jackie throughout the campaign and helped connect her with fashion designer Oleg Cassini, who became chief designer to the first lady".[24] "I can remember Jackie Kennedy, right after she moved into the White House...It wasn't even like a country club, if you see what I mean--plain." Vreeland occasionally gave Mrs. Kennedy advice about clothing during her husband's administration, and small advice about what to wear on Inauguration Day in 1961.[25]

In spite of being extremely successful, Diana Vreeland was paid a relatively small salary by the Hearst Corporation, which owned Harper's Bazaar. Vreeland said that she was paid $18,000 a year from 1936 with a $1,000 raise, finally, in 1959. She speculated that newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst's castle in San Simeon, California, "must have been where the Hearst money went".[26]

Vogue 1963–1971 and the Metropolitan Museum of Art

According to some sources, hurt that she was passed over for promotion at Harper's Bazaar in 1957, she joined Vogue in 1962. She was editor-in-chief from 1963 until 1971. Vreeland enjoyed the 1960s enormously because she felt that uniqueness was being celebrated. "If you had a bump on your nose, it made no difference so long as you had a marvelous body and good carriage."[20]

Vreeland sent memos to her staff urging them to be creative. One said, "Today let's think pig white! Wouldn't it be wonderful to have stockings that were pig white! The color of baby pigs, not quite white and not quite pink!"[27] During her tenure at the magazine, she discovered the sixties "youthquake" star Edie Sedgwick. In 1984, Vreeland explained how she saw fashion magazines. "What these magazines gave was a point of view. Most people haven't got a point of view; they need to have it given to them—and what's more, they expect it from you. [...][I]t must have been 1966 or '67. I published this big fashion slogan: This is the year of do it yourself. [...][E]very store in the country telephoned to say, 'Look, you have to tell people. No one wants to do it themselves-they want direction and to follow a leader!'"[28]

After she was fired from Vogue, she became consultant to the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1971.[29] By 1984, according to Vreeland's account, she had organized twelve exhibitions.[30] Artist Greer Lankton created a life-size portrait doll of Vreeland that is on display in the Costume Institute's library.

Later years

In 1984, Vreeland wrote her autobiography, D.V.[31]

In 1989, she died of a heart attack at age 85 at Lenox Hill Hospital, on Manhattan's Upper East Side in New York City.

Diana Vreeland Estate

The Diana Vreeland Estate is administered by her grandson, Alexander Vreeland, Frederick's son. The responsibility was given to him by her sons, Fredrick and Tim. The official Diana Vreeland website was launched in September 2011. Created and overseen by her estate, DianaVreeland.com[32] is dedicated to her work and career, presenting her accomplishments and influence, and revealing how and why she achieved her notoriety and distinction.

Film portrayals

Vreeland was portrayed in the film Infamous (2006) by Juliet Stevenson. She was also portrayed in the film Factory Girl (2006) by Illeana Douglas. Her life was documented in Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel (2012).

Diana Vreeland Parfums is featured in the opening scene of Ocean's 8.

References in film, television, theatre and literature

In the 1995 film To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar, Vida Boheme (Patrick Swayze) gives a copy of Vreeland's autobiography to a thrift-store clerk and tells him to "commit sections to memory". Later, the clerk quotes a passage that reads "That season we were loaded with pizazz. Earrings of fuchsia and peach. Mind you, peach. And hats. Hats, hats, hats, for career girls. How I adored Paris."

In 1982, she met over dinner with author Bruce Chatwin, who wrote a touching memoir of their dinner conversation in a half-page slice-of-life, entitled "At Dinner with Diana Vreeland".[33]

In 1980, she was lauded in an article about social climbing in The New Yorker.

In the 1966 film Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?, Miss Maxwell (Grayson Hall) portrays an extravagant American expatriate fashion magazine editor. The film's director, William Klein, worked briefly for Vreeland and has confirmed the outrageous character in Polly Maggoo was based on Vreeland.[34]

Maggie Prescott, a fashion magazine editor in Funny Face is loosely based on Diana Vreeland.

In the 1941 musical Lady in the Dark by Moss Hart, Kurt Weill and Ira Gershwin the character of Alison Du Bois was based on Vreeland.[35]

In October 1996, Mary Louise Wilson portrayed Vreeland in a one-woman play called Full Gallop, which she had written together with Mark Hampton.[36] The play takes place the day after Vreeland's return to New York City from her 4-month escape to Paris after being fired from Vogue. It was produced at the Westside Theatre in New York City, and directed by Nicholas Martin.

In the 2011 book "Damned" by Chuck Palahniuk, the main character (Madison Spencer) receives a pair of high heels from the character Babette. "In one hand, Babette holds a strappy pair of high heels. She says, "I got these from Diana Vreeland. I hope they fit...".

In 2016, drag queen Robbie Turner portrayed Vreeland in the annual Snatch Game on the 8th season of RuPaul's Drag Race.

See also

- Monk with a Camera, a film about Nicholas Vreeland, who is Diana Vreeland's grandson.

References

- Diana Vreeland. 2002. p. 246. ISBN 0-688-16738-1.

- She was coy about her age, and genuinely perplexed. Diana's confusion was the result of a misreading. The genealogist Philippe Chapelin of genfrance.com has clarified that there was no discrepancy and that Diana was born on September 29, 1903. The misunderstanding came from the abbreviation "7bre" in her bulletin de naissance, which Diana took to mean "July" but is actually shorthand for "September", "7 does not mean July but seven, that is French 'Sept.'" (similar abbreviations are used for all the other months of autumn), according to Amanda Mackenzie Stuart, Diana Vreeland – Empress of Fashion, London: Thames & Hudson, 2013, p. 338.

- "World's Best Dressed Women". The International Hall of Fame: Women. 1964. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- Ultimate Style – The Best of the Best Dressed List. 2004. p. 90. ISBN 2 84323 513 8.

- Diana Vreeland papers 1899-2000 (bulk 1930-1989), The New York Public Library – Archives & Manuscripts. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- Bowles, Hamish. "Diana Vreeland – Voguepedia." Vogue Fashion, Features, and More on Vogue.com. Retrieved March 15, 2012. http://www.vogue.com/voguepedia/ Archived 2013-05-18 at the Wayback Machine

- "Council of American Ambassadors Membership Frederick Vreeland" Archived 2010-09-17 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- Diana Vreeland – Empress of Fashion. 2013. pp. 82. ISBN 978-0-500-51681-2.

- Gilbert, Lynn (2012-12-10). Particular Passions: Diana Vreeland. Women of Wisdom Series (1st ed.). New York City: Lynn Gilbert Inc. ISBN 978-1-61979-985-1.

- "Watch Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel () online - Amazon Video". www.amazon.com. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- Vreeland, Diana (1985) [1984]. D. V. New York: Vintage. pp. 116–117. ISBN 0-394-73161-1.

- "The Divine Mrs. V". Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- D.V., p. 122.

- Harper's Bazaar March 1943", photography Louise Dahl-Wolfe.

- "Lauren Bacall: The Souring of a Hollywood Legend". Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- "Diana Vreeland 1906–1989" Archived 2013-08-31 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- D.V., p. 144.

- "National Museum of Women In The Arts Louise Dahl-Wolfe". Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- "Nancy White, 85, Dies; Edited Harper's Bazaar in the 60s". Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- "The Divine Mrs. V".

- "Diana Vreeland, Editor, Dies; Voice of Fashion for Decades", The New York Times, August 23, 1989.

- "Diana Vreeland 1903–1989".

- "The All Seeing Diana Vreeland". Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- "Portrait of the Kennedys", Smithsonian Magazine, October 26, 2007. Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- D.V., pp. 223–24.

- D.V., p. 189.

- Mahon, Gigi (1989-09-10). "S.I. Newhouse and Conde Nast; Taking Off The White Gloves".

- D.V., p. 198.

- Morris, Bernadine. "Review/Fashion; Celebrating the Flair That Was Vreeland". Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- D.V., p. 229.

- Vreeland, Diana (2011-04-19). D.V. (Reprint ed.). New York, NY: Ecco. ISBN 9780062024404.

- http://www.DianaVreeland.com

- "Dinner with Diana Vreeland," in: Bruce Chatwin, What Am I Doing Here (New York: Viking, 1989).

- Grayson Hall: A Hard Act to Follow (2006).

- Bruce D. McClung: Lady in the Dark – Biography of a Musical (2007), p. 10.

- "Dramatists Play Service, Inc". Retrieved February 18, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diana Vreeland. |

- Diana Vreeland Estate

- Diana Vreeland Estate at Facebook

- Diana Vreeland at FMD

- Diana Vreeland at IMDb

- Voguepedia Diana Vreeland

- The Lady in Red

- Diana Vreeland papers, 1899–2000 (bulk 1930–1989), held by the Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library

- Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel (2012 film website).

| Media offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Jessica Daves |

Editor of American Vogue 1963–1971 |

Succeeded by Grace Mirabella |