David Eagleman

David Eagleman (born April 25, 1971) is an American neuroscientist, author, and science communicator. He teaches neuroscience at Stanford University[1] and is CEO and co-founder of Neosensory, a company that develops devices for sensory substitution.[2] He also directs the non-profit Center for Science and Law, which seeks to align the legal system with modern neuroscience[3] and is Chief Science Officer and co-founder of BrainCheck, a digital cognitive health platform used in medical practices and health systems.[4] He is known for his work on brain plasticity,[5] time perception,[6] synesthesia,[7] and neurolaw.[8]

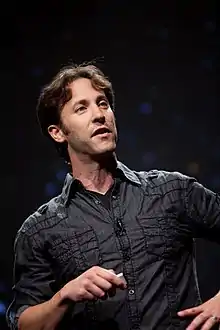

David Eagleman | |

|---|---|

Eagleman in 2010 | |

| Born | April 25, 1971 (age 49) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Rice University, Baylor College of Medicine, Salk Institute |

| Known for | Time perception, brain plasticity, synesthesia, neurolaw. PBS television series: The Brain with David Eagleman. Books: Sum: Forty Tales from the Afterlives, Incognito, The Brain: The Story of You, The Runaway Species |

| Awards | Guggenheim Fellowship, Science Educator of the Year – Society for Neuroscience |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Neuroscience |

| Institutions | Stanford University |

| Website | www deagle |

He is a Guggenheim Fellow and a New York Times-bestselling author published in 32 languages.[9][10][11][12][13] He is the writer and presenter of the Emmy-nominated international television series, The Brain with David Eagleman.[14]

Biography

Eagleman was born in New Mexico to Arthur and Cirel Egelman, a physician and biology teacher, respectively.[15] Eagleman decided to change his name from Egelman after discovering alternative spellings in personal genealogy research.[16] An early experience of falling from a roof raised his interest in understanding the neural basis of time perception.[17][18] He attended the Albuquerque Academy for high school. As an undergraduate at Rice University, he majored in British and American literature. He spent his junior year abroad at Oxford University and graduated from Rice in 1993.[19] He earned his PhD in Neuroscience at Baylor College of Medicine in 1998, followed by a postdoctoral fellowship at the Salk Institute.

Eagleman is currently an adjunct professor at Stanford University, after directing a neuroscience research laboratory for 10 years at Baylor College of Medicine. He serves as the Chief Science Advisor for the Mind Science Foundation, and is the youngest member of the board of directors of the Long Now Foundation. Eagleman is a Guggenheim Fellow,[20] a Fellow of the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies,[21] and a council member on the World Economic Forum's Global Agenda Council on Neuroscience & Behavior.[22] He was voted one of Houston's Most Stylish men,[23] and Italy's Style fashion magazine named Eagleman one of the "Brainiest, Brightest Idea Guys" and featured him on the cover.[24] He was awarded the Science Educator Award by the Society for Neuroscience.[25] He has spun off several companies from his research,[26] including BrainCheck,[4] which helps medical professionals assess and diagnose cognitive impairment and dementia, and NeoSensory,[27] which uses sound-to-touch sensory substitution to feed data streams into the brain, as described in his TED talk.[5]

Eagleman has been profiled in magazines such as the New Yorker,[6] Texas Monthly,[28] and Texas Observer,[29] on pop-culture television programs such as The Colbert Report[30] and on the scientific program Nova Science Now.[31] Stewart Brand wrote that "David Eagleman may be the best combination of scientist and fiction-writer alive".[32] Eagleman founded Deathswitch, an internet based dead man's switch service, in 2007.[33]

As opposed to committing to strict atheism or to a particular religious position, Eagleman refers to himself as a possibilian,[34][35] which distinguishes itself from atheism and agnosticism by studying the structure of the possibility space.

Scientific specializations

Sensory substitution

Sensory substitution refers to feeding information into the brain via unusual sensory channels (for example, audition through vibrations on the skin). In a TED talk,[5] Eagleman unveiled a method for using sound-to-touch sensory substitution to feed data streams into the brain.[36] In 2015 he launched the company Neosensory,[37] headquartered in Palo Alto, California. As of 2020, Neosensory has raised 16 million dollars in venture funding.[38][39] Eagleman's book Livewired describes the history and future of sensory substitution.

Time perception

Eagleman's scientific work combines psychophysical, behavioral, and computational approaches to address the relationship between the timing of perception and the timing of neural signals.[40][41][42] Areas for which he is known include temporal encoding, time warping, manipulations of the perception of causality, and time perception in high-adrenaline situations.[43] In one experiment, he dropped himself and other volunteers from a 150-foot tower to measure time perception as they fell.[44] He writes that his long-range goal is "to understand how neural signals processed by different brain regions come together for a temporally unified picture of the world".[45]

Synesthesia

Synesthesia is an unusual perceptual condition in which stimulation to one sense triggers an involuntary sensation in other senses. Eagleman is the developer of The Synesthesia Battery, a free online test by which people can determine whether they are synesthetic.[46] By this technique he has tested and analyzed thousands of synesthetes,[47] and has written a book on synesthesia with Richard Cytowic, entitled Wednesday is Indigo Blue: Discovering the Brain of Synesthesia.[7] Eagleman has proposed that sensory processing disorder, a common characteristic of autism, may be a form of synesthesia[48]

Visual illusions

Eagleman has published extensively on what visual illusions[49] tell us about neurobiology, concentrating especially on the flash lag illusion and wagon wheel effect.

Television

Eagleman wrote and hosted The Brain with David Eagleman, an international television documentary series for which he was the writer, host, and executive producer[54][55][56][57][58][59] The series debuted on PBS in America in 2015,[60] followed by the BBC in the United Kingdom and the SBS in Australia before worldwide distribution. The New York Times listed it as one of the best television shows of the year.[61] In 2016, the series was nominated for an Emmy Award.

In 2018 he made a Netflix documentary, The Creative Brain, based on his book The Runaway Species with Anthony Brandt. In that documentary, he interviews creators such as Tim Robbins, Michael Chabon, Grimes, Dan Weiss, Kelis, Robert Glasper, Nathan Myhrvold, Michelle Khine, Nick Cave, Bjarke Ingels, and others.[62]

Eagleman serves as the scientific advisor for the HBO television series Westworld.[63][64] He previously served as the science advisor for the TNT television drama, Perception, starring Eric McCormack as a schizophrenic neuropsychiatrist.[65] In that role, Eagleman wrote one of the episodes, Eternity.[66]

Books

Wednesday is Indigo Blue: Discovering the Brain of Synesthesia

Eagleman's book on synesthesia, co-authored with neurologist Richard Cytowic, compiles the modern understanding and research about this perceptual condition. The afterword for the book was written by Dmitri Nabokov, the son of Vladimir Nabokov, a famous synesthete. The book won the Montaigne Medal for "books that illuminate, progress, or redirect thought".[67]

Sum

Eagleman's work of literary fiction, Sum: Forty Tales from the Afterlives, is an international bestseller published in 32 languages. The Observer wrote that "Sum has the unaccountable, jaw-dropping quality of genius",[11] The Wall Street Journal called Sum "inventive and imaginative",[68] and the Los Angeles Times hailed the book as "teeming, writhing with imagination".[12] In The New York Times Book Review, Alexander McCall Smith described Sum as a "delightful, thought-provoking little collection belonging to that category of strange, unclassifiable books that will haunt the reader long after the last page has been turned. It is full of tangential insights into the human condition and poetic thought experiments... It is also full of touching moments and glorious wit of the sort one only hopes will be in copious supply on the other side."[10] Sum was chosen by Time Magazine for their Summer Reading list,[69] and selected as Book of the Week by both The Guardian[70] and The Week.[71] In September 2009, Sum was ranked by Amazon as the #2 bestselling book in the United Kingdom.[72][73] Sum was named a Book of the Year by Barnes and Noble, The Chicago Tribune, The Guardian, and The Scotsman.

The Safety Net (previously titled Why the Net Matters)

In 2020, Eagleman published The Safety Net: Surviving Pandemics and Other Disasters, an updated and re-titled version of a book he had published in 2010: Why the Net Matters (Canongate Books). in the book, he argues that the advent of the internet mitigates some of the traditional existential threats to civilizations.[74] In keeping with the book's theme of the dematerialization of physical goods, he chose to publish the manuscript as an app for the iPad rather than a physical book. The New York Times Magazine described Why the Net Matters as a "superbook", referring to "books with so much functionality that they're sold as apps".[75] Stewart Brand described Why the Net Matters as a "breakthrough work". The project was longlisted for the 2011 Publishing Innovation Award by Digital Book World.[76] Eagleman's talk on the topic, entitled "Six Easy Ways to Avert the Collapse of Civilization", was voted the #8 Technology talk of 2010 by Fora.tv.

Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain

Eagleman's science book Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain is a New York Times bestseller[9] and was named a Best Book of the Year by Amazon,[77] the Boston Globe,[78] and the Houston Chronicle.[79] Incognito was reviewed as "appealing and persuasive" by The Wall Street Journal[80] and "a shining example of lucid and easy-to-grasp science writing" by The Independent.[81] The book explores the brain as being a "team of rivals", with parts of the brain constantly "fighting it out" among each other.[82]

The Brain: The Story of You

In 2015, The Brain came out as a companion book to the television series The Brain with David Eagleman.

Brain and Behavior: A Cognitive Neuroscience Perspective

In 2016, Eagleman co-authored this Cognitive Neuroscience textbook with Jonathan Downar. The textbook is published by Oxford University Press, and is used by many universities around the world, including Stanford and Columbia.

The Runaway Species

In 2017 Eagleman and co-author Anthony Brandt (a music composer) wrote The Runaway Species, an examination of human creativity. The book was described by the journal Nature as "A lively exploration of the software our brains run in search of the mother lode of invention… It sweeps the reader through examples from engineering, science, product design, music and the visual arts to trace the roots of creative thinking."[83] The Wall Street Journal wrote that "the authors look at art and science together to examine how innovations — from Picasso's initially offensive paintings to Steve Jobs's startling iPhone — build on what already exists... This manifesto of sorts shows how both disciplines foster creativity."[84]

Livewired: The Inside Story of the Ever-Changing Brain

In 2020, Eagleman published Livewired: The Inside Story of the Ever-Changing Brain, a nonfiction book about neuroplasticity. As of late 2020, it is nominated for the Pulitzer Prize. A Kirkus review described the book as "outstanding popular science,"[85] while New Scientist magazine wrote that "Eagleman brings the subject to life in a way I haven't seen other writers achieve before."[86] The Harvard Business Review wrote that Livewired "gets the science right and makes it accessible... completely upending our basic sense of what the brain is in the process."[87] The Wall Street Journal wrote that "since the passing of Isaac Asimov, we haven't had a working scientist like Eagleman, who engages his ideas in such a variety of modes. Livewired reads wonderfully, like what a book would be if it were written by Oliver Sacks and William Gibson, sitting on Carl Sagan's front lawn."[88]

Works

- Wednesday Is Indigo Blue: Discovering the Brain of Synesthesia, co-authored with Richard Cytowic, MIT Press, 2009

- Sum: Forty Tales from the Afterlives, Pantheon, 2009 (Fiction)

- The Safety Net: Surviving Pandemics and Other Disasters, Canongate, 2020 (originally published as Why the Net Matters, Canongate, 2010)

- Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain, Pantheon, 2011

- The Brain with David Eagleman, a PBS television series, 2015

- The Brain: The Story of You, Canongate, 2015

- Brain and Behavior: A Cognitive Neuroscience Perspective, co-authored with Jonathan Downar, Oxford University Press, 2016

- The Runaway Species, co-authored with Anthony Brandt, Catapult, 2017

- Livewired: The Inside Story of the Ever-Changing Brain, Penguin Random House, 2020

References

- Stanford University: David Eagleman

- Neosensory

- The Center for Science and Law

- "Cognitive Health Platform for Everyday Clinical Use". BrainCheck. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- David Eagleman TED talk, March 18, 2015.

- The Possibilian: David Eagleman and the Mysteries of the Brain, The New Yorker, April 25, 2011.

- Cytowic RE and Eagleman DM (2009). Wednesday is Indigo Blue: Discovering the Brain of Synesthesia. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- The Brain on Trial, David Eagleman, The Atlantic, July 2011

- Inside the List, New York Times, June 10, 2011

- Alexander McCall Smith, Eternal Whimsy: Review of David Eagleman's Sum, New York Times Book Review, June 12, 2009. Retrieved on 2009-06-14.

- Geoff Dyer, Do you really want to come back as a horse?: Geoff Dyer is bowled over by a neuroscientist's exploration of the beyond, The Observer, June 7, 2009. Retrieved on 2009-06-12.

- David Eagleman's Sum (book review), Los Angeles Times, February 1, 2009. Retrieved on 2009-02-08.

- International editions of SUM. Retrieved on 2015-03-19.

- PBS: The Brain with David Eagleman

- BCM dissertation acknowledgements

- Jumping to conclusions

- Radiolab: Falling, September 2010.

- Ripley, Amanda (2008). The Unthinkable: Who Survives When Disaster Strikes – and Why. Crown Books. pp 65–67.

- "Association of Rice Alumni". Rice.edu. Archived from the original on June 4, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- Guggenheim Fellowship Awards 2011

- "David Eagleman".

- "World Economic Forum Global Agenda Council on Neuroscience & Behaviour" (PDF).

- Houston Magazine's Men of Style 2011

- David Eagleman, Style magazine, December 2011, Issue 12, pp 75–80.

- Science Educator Award, Society for Neuroscience, October 2012.

- Google Scholar

- Neosensory, Inc

- Is David Eagleman Neuroscience's Carl Sagan?

- The Soul Seeker: A neuroscientist's search for the human essence, Texas Observer, May 28, 2010.

- Colbert Report: David Eagleman, Aired July 21, 2011.

- Profile: David Eagleman, Nova Science Now, Aired February 2, 2011.

- Introduction to Eagleman lecture at the Long Now Foundation, April 1, 2010.

- , Houston Chronicle, January 9, 2007.

- Beyond god and atheism: Why I am a possibilian, David Eagleman, New Scientist, September 27, 2010.

- Stray questions for David Eagleman, The New York Times Paper Cuts, July 10, 2009.

- Novich SD & Eagleman DM (2015). Using space and time to encode vibrotactile information: toward an estimate of the skin's achievable throughput. Experimental Brain Research. 233 (10): 2777-2788.

- Neosensory

- Neosensory announces 10 million Series A financing round, Business Insider, January 2019]

- Crunchbase - Neosensory

- Eagleman DM (2009). Brain Time. In What's Next? Dispatches on the Future of Science. Ed: Max Brockman. Vintage Books.

- Burdick, A (2006). The mind in overdrive. Discover Magazine, 27 (4), 21–22.

- Eagleman, DM (2008). "Human time perception and its illusions" (PDF). Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 18 (2): 131–6. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2008.06.002. PMC 2866156. PMID 18639634.

- Stetson C, Fiesta MP, Eagleman DM (2007). Does time really slow down during a frightening event? PLoS One. 2(12):e1295.

- Choi, CQ. Time doesn't really freeze when you're freaked, MSNBC, December 11, 2007.

- Eagleman Stanford website

- Eagleman DM, Kagan AD, Nelson SN, Sagaram D, Sarma AK (2007). A standardized test battery for the study of Synesthesia" Journal of Neuroscience Methods 159: 139–145.

- Novich, SD; Cheng, S; Eagleman, DM (2011). "Is synesthesia one condition or many? A large-scale analysis reveals subgroups" (PDF). Journal of Neuropsychology. 5 (2): 353–371. doi:10.1111/j.1748-6653.2011.02015.x. PMID 21923794.

- The blended senses of synesthesia, Los Angeles Times, February 20, 2012.

- https://eagleman.com/papers/Eagleman.NatureRevNeuro.Illusions.pdf

- The Brain and The Law, Lecture at the Royal Society for the Arts, London, England, April 21, 2009.

- Eagleman DM, Correro MA, Singh J (2009). Correro, Mark A.; Eagleman, David M. (April 9, 2009). "Why Neuroscience Matters For a Rational Drug Policy". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help), Minnesota Journal of Law, Science and Technology. - The Center for Science and Law

- "You are your brain" – David Eagleman on transforming the criminal justice system, Reason TV, April 2010. Retrieved on 2012-02-19.

- "David Eagleman's New TV Show 'The Brain' Gets Inside Your Head". Newsweek. October 15, 2015. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- "David Eagleman Wants You to Meet Your Brain". New York Magazine. October 14, 2015. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- Gareth Cook (October 6, 2015). "Exploring the Mysteries of the Brain - David Eagleman answers questions about his major PBS series". Scientific American.

- David DiSalvo (October 13, 2015). "The Cosmos Inside Your Head: Neuroscientist David Eagleman Tells The Story Of The Brain On PBS". Forbes Magazine.

- Daniel Bor (October 1, 2015). "Neuroscience: The mechanics of mind". Nature. 526 (7571): 41–42. Bibcode:2015Natur.526...41B. doi:10.1038/526041a.

- Michael Hardy (October 14, 2015). "Is David Eagleman Neuroscience's Carl Sagan?". Texas Monthly.

- "The Brain with David Eagleman". Public Broadcasting Service.

- "The Best TV Shows of 2015". The New York Times. December 7, 2015. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- "The Creative Brain on Netflix".

- "Free will, AI, and vibrating vests: investigating the science of Westworld". Science. May 2, 2018. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- "'Westworld' Science Advisor Talks Brains and AI". Discover. June 7, 2018. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- Internet Movie Database, Full Cast & Crew, Perception

- Internet Movie Database, Eternity episode of Perception

- Montaigne Medal Winners

- Stark, A. In Our End Is Our Beginning, Wall Street Journal, February 13, 2009.

- TIME Magazine's 2009 Summer Reading list, July 13, 2009.

- Nick Lezard, Life after life explained, The Guardian, June 13, 2009.

- Book of the week: Sum: Forty Tales From the Afterlives by David Eagleman, The Week, March 6, 2009.

- Stephen Fry tweet sends book's sales rocketing, The Guardian, September 11, 2009.

- Stephen Fry's Twitter posts on David Eagleman novel sparks 6000% sales spike, The Telegraph, September 11, 2009.

- A new species of book, BBC Radio 4, Today Programme, December 13, 2010

- Watch Me, Read Me, New York Times Magazine, January 16, 2011

- DBW Innovation Awards longlist, retrieved January 16, 2011.

- Amazon.com Best Science Books of 2011

- Boston Globe: Best Books of the Year 2011

- Bookish: Best Books of 2011

- The Stranger Within, Wall Street Journal, June 15, 2011

- Incognito review, The Independent, April 17, 2011

- Fresh Air with Terry Gross (May 31, 2011). "'Incognito': What's Hiding In The Unconscious Mind". National Public Radio (U.S.) WHYY, Inc. Press the blue button to hear the audio of the interview.

- Jones, Dan (2017). "Neuroscience: The mother lode of invention". Nature. 550 (7674): 34–35. Bibcode:2017Natur.550...34J. doi:10.1038/550034a.

- Fall Books for Tech Lovers—and Those Who Want to Escape It, Wall Street Journal, Oct 5, 2017

- Livewired - Kirkus Reviews, Aug 25, 2020

- Livewired review: How a 6-year-old had half his brain removed and recovered in 3 months, New Scientist, 23 Sept, 2020

- Unartificial Intelligence, Harvard Business Review, Nov-Dec 2020

- "Livewired Book Review". The Wall Street Journal.