Dadaab

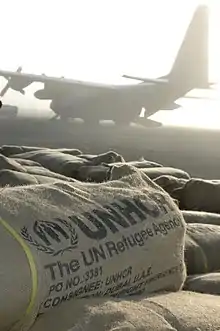

Dadaab is a semi-arid town in Garissa County, Kenya . It is the site of a UNHCR base hosting 223,420[2] registered refugees and asylum seekers in three camps (Dagahaley, Hagadera and Ifo,) as of 13 May 2019,[1] making it the third-largest such complex in the world.[3][4][5][6] The center is run by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and its operations are financed by foreign donors.[7] In 2013, UNHCR, the governments of Kenya and Somalia signed a tripartite agreement facilitating the repatriation of Somali refugees at the complex.[8]

Dadaab | |

|---|---|

Ifo II camp in Dadaab. | |

Dadaab Location in Kenya | |

| Coordinates: 00°03′11″N 40°18′31″E | |

| Country | |

| County | Garissa County |

| Population (January 2018) | |

| • Total | ~235,269[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

Establishment

Construction

The Dadaab camps Dagahaley, Hagadera and Ifo were constructed in 1992. In 2011 and 2013, two new refugee camps were opened when 164,000 new refugees from Somalia arrived, due to severe drought.[3][9] The Ifo II camp extension was originally constructed in 2007 by the Norwegian Refugee Council, in response to major flooding that destroyed over 2,000 homes in the Ifo refugee camp. However, legal problems with the Kenyan Government prevented Ifo II from fully opening for relocation, until 2011.[10] As of 13 May, Hagadera was the largest of the camps, containing just over 74,744 individuals and 17,490 households.[3] Ifo refugee camp, on the other hand, is the smallest camp with 65,974 refugees.[3] Former Kambioss and Ifo2 refugee camps were closed in April 2017 and May 2018, respectively.

Ifo camp was first settled by refugees from the civil war in Somalia. The UNHCR subsequently made efforts to improve the premises. As the population of the camps in Dadaab grew, UNHCR commissioned the German architect Werner Schellenberg to draw the original design for Dagahaley Camp, as well as the Swedish architect Per Iwansson, who designed and initiated the establishment of Hagadera camp.

Population growth and decline

People first began arriving at the Dadaab complex shortly after its construction in 1992, with most escaping the Somali Civil War.[11] When refugees arrive at the camp, they are registered and fingerprinted by the Kenyan government.[12] However, the camps themselves are managed by the UNHCR, with other organizations directly in charge of specific aspects of the resident' lives. CARE oversees Water and Sanitation Hygiene as well as warehouse management and the World Food Programme (WFP) distributes food rations. Until 2003, only Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) provided refugees with access to health-care. Now, healthcare is decentralized. Kenya Red Cross Society (KRCS) provides health care services in ifo refugee camp, International Rescue committee (IRC) in Hagadera and Medicins Sans Frontieres in Dagahley refugee camp. Although refugees arriving at Dadaab receive assistance from each of these organizations, aid is often not immediate due to overcrowding.[13] Other relief organizations include Danish Refugee Agency (DRC), Norwegian Refugee Agency (NRC), Windle International, Lutheran World Federation, Center for Victims of Torture, In July 2011, due to a drought in Eastern Africa, over 1,000 people per day were arriving in need of assistance.[14] The influx reportedly placed great strain on the resources, as the capacity of the camps was around 90,000, whereas the camps hosted 439,000 refugees in July 2011 according to the UNHCR.[15] The number was predicted to increase to 500,000 by the end of 2011 according to estimates from Médecins Sans Frontières. Those population figures at the time made Dadaab the largest refugee camp in the world.[16] According to the Lutheran World Federation, military operations in the conflict zones of southern Somalia and a scaling up of relief operations had by early December 2011 greatly reduced the movement of migrants into Dadaab.[17]

| Location | 2014[18] | 2013[19] | 2012[20] | 2011[21] | 2010[22] | 2009[23] | 2008[24] | 2007[25] | 2006[26] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dagahaley | 88,486 | 104,565 | 121,127 | 122,214 | 93,470 | 93,179 | 65,581 | 39,626 | 39,526 |

| Hagadera | 106,968 | 114,729 | 139,483 | 137,528 | 101,506 | 83,518 | 90,403 | 70,412 | 59,185 |

| Ifo | 83,750 | 99,761 | 98,294 | 118,972 | 97,610 | 79,424 | 79,469 | 61,832 | 54,157 |

Demographics

Before the UNHCR base was opened, the local town population traditionally consisted of nomadic ethnic Somali pastoralists, who were mainly camel and goat herders.[27] However, since the 1990s, an influx of refugees has dramatically shifted the demographics of the area. Most of the people living in Dadaab have fled various conflicts in the broader Eastern Africa region. The majority have come as a consequence of the civil war in southern Somalia as well as due to droughts.[28] According to Human Rights Watch, most of these displaced persons belong to the Bantu ethnic minority population as well as the Rahanweyn clan. Most of the latter have migrated from the southern Jubba Valley and the Gedo region, while the remainder have arrived from Kismayo, Mogadishu and Bardera.[29]

In 2005, around 97% of registered refugees at Dadaab were Muslims from Somalia. The remainder mainly consisted of Muslims from the Somali Region (Ogaden) in Ethiopia, Ethiopian Christians and Sudanese Christians, totaling 4,000 individuals. While the Muslim minorities did not face any persecution, tensions with the Christian minorities were reportedly high.[30]

According to the UNHCR, 80% of residents were women and children and 95% were Somalia nationals as of mid-2015.[4][31] Of the registered refugee population from Somalia, the number of men and women is equal, but only 4% of the total population is over the age of sixty.[3] Each year, thousands of children are born in the Dadaab camps. A number of adults have spent their entire lives as refugees in the complex.[3][27]

Infrastructure

.jpg.webp)

The Dadaab refugee camp complex is so vast that it has been compared to a city, with urban features such as high population density, economic activity, and concentration of infrastructure.[32] Like a typical urban area, Dadaab contains public service buildings such as schools and hospitals.[27] The Ifo II camp, for example, includes religious spaces, a disability center, police stations, graveyards, a bus station, and more. In addition, it is designed in a grid-like pattern, with the market on one side and a green belt at the center of the many lines of tents.[33] Despite these many amenities, however, the camps are crowded and have few signposts, making them confusing and difficult to navigate for new arrivals.[27]

Refugees in Dadaab typically live in tents, which are made of plastic sheeting and distributed by the UNHCR.[34] Although many residents have voluntarily repatriated, the camps are still overcrowded and exceed their intended capacity. In addition to tents, some residents have built makeshift homes for shelter and to escape the heat of the sun.[13] On average, four people live together in each household.[3]

Living conditions

With camps filled to capacity, NGOs have worked to improve camp conditions. However, as most urban planners frequently lack the tools to contend with such complex issues, there have been few innovations to improve Dadaab. Opportunities remain such as upgrading and expansion processes for communications infrastructure, environmental management and design.[35] Aside from the infrastructure, some of the factors affecting quality of life for refugees are health-care and diet, education, environment, security, and their economic and legal status.

Education

According to the Kenya Commissioner for Refugees, when migrants first began arriving in Dadaab town from Somalia, they were all educated.[11] An assessment survey completed in 2011 found that access to education in Dadaab was considerably limited, restricting the ability of refugees at the center to find jobs and become less reliant on aid organizations. Dadaab had only one secondary school; those who managed to be educated there could receive jobs working for aid agencies such as CARE, WFP, or GTZ that distribute resources to refugees. Those who were uneducated could pursue jobs in restaurants or helping load and unload trucks. Many chose other modes of subsistence. In 2011, only around 48% of children in Dadaab were enrolled in school.[27]

In response, the Ministry of Education of Somalia announced that all high school students at the center who were Somali citizens would be eligible for higher education scholarships.[36] To further improve the education standards, a new European Union-funded project was launched in 2013. The initiative was earmarked for three years, with $4.6 million allocated toward its syllabus. It included new classrooms for all local schools, adult programs, girls' special education, and scholarships for elite students based on merit. 75% of the funds were set aside for refugees at the complex, and 25% were reserved for local constituencies in Lagdera and Fafi.[37]

Health care

The German Technical Cooperation (GTZ) provides basic health-care.[9] On a typical day, around 1,800 refugees get outpatient treatment in hospitals inside the camps.[38] Since 2015, Dadaab has had the largest solar-powered borehole in Africa, which is equipped with 278 solar panels and provides 16,000 residents of the complex with a daily average of about 280,000 litres of water.[39]

Local health risks are complicated by overcrowding. They include diarrhea, pulmonary issues, fever, measles, acute jaundice syndrome, and cholera.[40][41] Hepatitis E is also a potential issue, as the premises often have substandard sanitary facilities and unclean water.[40]

One reason refugees arrive at the camps is displacement caused by natural disasters. By the end of 2011, more than 25% of residents at the complex had come as a result of a drought in Eastern Africa.[40] Individuals arriving under these conditions were already malnourished, and once at the camps they could experience additional food scarcity.[13] Although malnutrition is a contributing factor to high death rates among children, it has been observed that life expectancy at the complex is positively correlated with years of inhabitation.[41]

Refugees receive food rations containing cereal, legumes, oil, and sugar from the World Food Programme (WFP).[42] Due to overcrowding and lack of resources, they are not eligible for their initial rations until 12 days after arrival, on average.[13] The rations are generally first distributed to children under the age of five because they are at the greatest health risk.[12] Markets at each of the camps have fresh food for sale. However, due to limited income opportunities, most residents are unable to afford them.[42] Some have used innovations such as multi-storey gardens to supplement rations. These require only basic supplies to construct and less water to maintain than normal gardens.[43]

Environment

Deforestation has an effect on the lives of Dadaab's residents.[44] Although they are typically required to remain in the camp, residents often have to venture out in search of firewood and water. They are thus obliged to travel farther due to deforestation in nearby areas.[44] This leaves women and girls vulnerable to violence as they journey to and from the complex.[44]

In 2006, flooding severely affected the region. More than 2,000 homes at the Ifo camp were destroyed, forcing the relocation of more than 10,000 refugees. The sole access road to the camp and to the town was also cut off by the floods, impeding the delivery of essential supplies. Humanitarian agencies present in the area worked together to bring vital goods to the area.[45][46]

In 2011, a drought in Eastern Africa caused a dramatic surge in the camps' population, placing greater strain on resources.[47] By February 2012, aid agencies had shifted their emphasis to recovery efforts, including digging irrigation canals and distributing plant seeds.[48] Long-term strategies by national governments in conjunction with development agencies are believed to offer the most sustainable results.[49] Rainfall had also surpassed expectations and rivers were flowing again, improving the prospects of a good harvest in early 2012.[50]

Security

Refugees at the UNHCR center are not protected by the Government of Kenya (GOK). This has contributed to dangerous living conditions and outbreaks of violence.[51] Because they are not protected under the law and are unable to possess a Kenyan national identification card, refugees are constantly at risk for arrest.[27][51] Additionally, the Kenyan government screens ethnic Somalis and Ethiopians separately from other residents due to their different physical characteristics. A special category in local police documents is earmarked for "Kenyan-Somalis".[52]

While all refugees at the camp are at risk of violence, the UNHCR and CARE have identified women and children as being particularly vulnerable.[53] They have created a department called 'Vulnerable Women and Children' (VWC) to tackle the issues surrounding violence against these populations.[53] As of August 2015, 60% of Dadaab's total population is under the age of 18, and there are equal numbers of men and women, so women and children make up a significant portion of the camps' demographics.[3] Specifically, the VWC department has identified orphans, widows, divorcees, rape victims and the disabled as the most vulnerable among all women and children.[53] They offer counseling, additional food rations and supplies, and advice on how to earn an income and be financially self-sufficient.[53] However, the effectiveness of these efforts has been questioned, and following an analysis by Dr. Aubone at St. Mary's University, more research and data is required to identify the best ways to prevent gender-based violence at the complex.[54]

Economic and legal status

Operations at the complex are financed by foreign donors.[7] Despite this, public perception in Kenya is that refugees in general cause a strain on the economy. Research, however, has found that many refugees are economically self-sufficient for the most part.[32][51]

In order to try to further increase the economic independence of refugees living in Dadaab, CARE has initiated microfinance programs, which are particularly important for encouraging women to start their own businesses.[55] However, recent scholarly research has identified some flaws with microfinance, arguing that it has unintended negative consequences.[56] Microfinance typically requires borrowers to pay very high interest rates, which can be detrimental to the poorest if any unexpected problems or crises arise.[56] Living in a community with other economically disadvantaged individuals can also make it difficult to make a profit from a business venture since potential customers are not able to afford the service or product that is being sold.[57] Others have argued that this is beneficial to individuals as a short-term economic solution, but that over the long-term it does not improve the economy as a whole.[58] CARE is also working to create more inclusive markets that refugees are able to participate in to profit off of their newly acquired skills and business ventures.[55]

Repatriation and resettlement

In November 2013, the Foreign Ministries of Somalia and Kenya and the UNHCR signed a tripartite agreement in Mogadishu paving the way for the voluntary repatriation of Somalia nationals living in Dadaab.[8][59][60] Both governments also agreed to form a repatriation commission to coordinate the return of the refugees.[59] This repatriation effort was in response to an attack on the Westgate shopping mall in Nairobi, and belief that Al-Shabaab, the militant group responsible for the attack, was using Dadaab to recruit new members.[61][62]

In 2014, the UNHCR assisted 3,562 refugees originating from Somalia to resettlement from Kenya.[63] Slightly over 2,000 individuals returned to the Luuq, Baidoa and Kismayo districts in southern Somalia under the repatriation project.[4] Despite these government endorsed repatriation schemes, the majority of the returnees have instead repatriated independently.[60] By February 2014, around 80,000 to 100,000 residents had voluntarily repatriated to Somalia, significantly decreasing the base's population.[8]

Following the Garissa University College attack in April 2015, which resulted in 148 deaths, the Kenyan government asked the UNHCR to repatriate the remaining refugees to a designated area in Somalia within three months.[64] The proposed closure was reportedly spurred by fear that Al-Shabaab was still recruiting members from Dadaab.[62] Some individuals reported that the anxiety caused by the Kenyan government repeatedly threatening to shut down the camps was enough to convince them to leave. Without job availability or reliable access to resources, greater opportunities existed for them outside of Dadaab.[34] Others questioned the government's rationale for closing the camps, dismissing the claims of terrorist elements as baseless and refusing to depart.[61] The three-month ultimatum passed without Dadaab being closed.[64]

The Federal Government of Somalia and UNHCR confirmed that the repatriation would continue to be voluntary in accordance with the tripartite agreement, and that eight districts in Somalia from where most of the individuals had come had officially been designated as safe for repatriation.[31][65] However, the Kenyan government has intermittently threatened to close down the Dadaab and Kakuma refugee camps. In May 2016, it declared that it had already disbanded the local Department of Refugee Affairs as part of the move, citing national security interests as the primary reason behind the forced repatriations.[66] The UNCHR regards the Kenyan authorities' unilateral declaration as irresponsible, and has sought to broker a deal to ensure that the complex remains open.[67] The threat of closure by the Kenyan government is believed to be a ploy on its part to leverage more foreign donations.[68] It also comes as the Somali federal authorities are challenging the Kenyan government at the International Court of Justice over demarcation of their respective territorial waters.[67]

See also

Notes

- "UNHCR Kenya Dadaab Refugee Complex". www.unhcr.org/ke/dadaab-refugee-complex.

- "UNHCR- Kenya Statistics Package" (PDF). UNHCR. 31 December 2020.

- "UNHCR Refugees in the Horn of Africa: Somali Displacement Crisis". UNHCR Refugees in the Horn of Africa: Somali Displacement Crisis. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- "UNHCR chief visits Somali port of Kismayo, meets refugee returnees". UNHCR. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- Hattem, Julian (24 January 2017). "Uganda's sprawling haven for 270,000 of South Sudan's refugees". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- "World's Largest Refugee Camps in 2018 | raptim".

- "Baobab - Africa". The Economist. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Nairobi to open mission in Mogadishu". Standard Digital. 19 February 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- Abdi, Awa M. (2010). "In Limbo: Dependency, Insecurity, and Identity Amongst Somali Refugees in Dadaab Camps". Bildhaan. 5: 17–34.

- Daniel Howden (August 2011). "UN and Kenya attacked over $60m Somali refugee camp that still stands empty". Independent.co.uk.

- "News in Review - Resource Guide - November 2011" (PDF). Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Inside world's biggest refugee camp - Al Jazeera Blogs". Al Jazeera Blogs. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- "Kenya: Fleeing Somalis Struggle To Find Shelter At The World's Largest Refugee Camp". MSF USA. Archived from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- "Inside world's biggest refugee camp". Blogs.aljazeera.net. 8 July 2011.

- "UN High Commissioner for Refugees applauds Kenya's decision to open Ifo II camp". UNHCR. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- "Dadaab: The World's Biggest Refugee Camp". English.aljazeera.net. 11 July 2011.

- "Number of Somali refugees declining due to aid and rainfall". Pcusa.org. 5 December 2011. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Table 16. Major locations and demographic composition of refugees and people in refugee-like situations, end-2014". UNHCR. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2013/annex_tables.zip

- http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2012/2012_Statistical_Yearbook_annex_tables_v1.zip

- http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2011/2011_Statistical_Yearbook_annex_tables_v1.zip

- http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2010/2011-SYB10-annex-tables.zip

- http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2009/2009-Statistical-Yearbook-Annex-Tables.zip

- http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2008/08-TPOC-TB_v5_external_PW.zip

- http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2007/annextables.zip

- http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2006/annextables.zip

- "No Direction Home: A Generation Shaped by Life in Dadaab". UNFPA - United Nations Population Fund. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- "Refugee Reports November 2002" (PDF). Refugees.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2009.

- "Human Rights Watch Plan" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. p. 17. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Adelman, Howard (2005). "Persecution of Christians in the Dadaab Refugee Camp". Journal of Human Rights. 4 (3): 353–362. doi:10.1080/14754830500257570. S2CID 144782233.

- "Interview: UN refugee chief stresses voluntary return of Somali refugees in Kenya". Goobjoog. 9 May 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- Montclos, Marc-Antoine Perouse De; Kagwanja, Peter Mwangi (1 June 2000). "Refugee Camps or Cities? The Socio-economic Dynamics of the Dadaab and Kakuma Camps in Northern Kenya". Journal of Refugee Studies. 13 (2): 205–222. doi:10.1093/jrs/13.2.205. ISSN 0951-6328.

- "Dadaab: how we're helping in the world's largest refugee camp". www.redcross.org.uk. Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- Dadaab, Mélanie Gouby in (20 May 2015). "Climate of fear in Dadaab refugee camp leads many to consider repatriation". the Guardian. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- [Mitchell Sipus] (December 2009). "Technology Based Development Opportunity Within Dadaab Refugee Camp, Kenya".

- "Somali students to receive scholarships for higher education". Digital Journal. 14 July 2011. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Somalia: Education Project Launched in Dadaab". Sabahi. 23 April 2013. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- http://www.unicnairobi.org/newsletter/UNNewsletter_March2012.pdf

- "More water from solar power in Dadaab, Kenya - European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations - European Commission". European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations. 16 November 2015.

- Ahmed, Jamal A.; Moturi, Edna; Spiegel, Paul; Schilperoord, Marian; Burton, Wagacha; Kassim, Nailah H.; Mohamed, Abdinoor; Ochieng, Melvin; Nderitu, Leonard (1 June 2013). "Hepatitis E Outbreak, Dadaab Refugee Camp, Kenya, 2012". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 19 (6): 1010–1011. doi:10.3201/eid1906.130275. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 3713845. PMID 23735820.

- Polonsky, Jonathan A.; Ronsse, Axelle; Ciglenecki, Iza; Rull, Monica; Porten, Klaudia (22 January 2013). "High levels of mortality, malnutrition, and measles, among recently-displaced Somali refugees in Dagahaley camp, Dadaab refugee camp complex, Kenya, 2011". Conflict and Health. 7 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/1752-1505-7-1. ISSN 1752-1505. PMC 3607918. PMID 23339463.

- "Fresh food vouchers for refugees in Kenya | ENN". www.ennonline.net. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- Corbett, Mary (2009). "Multi-Storey Gardens to Support Food Security" (PDF). Urban Agriculture.

- Salmio, Tiina. "Refugees and the Environment: An Analysis and Evaluation of UNHCR's Policies in 1992-2002" (PDF). Migrationinstitute.fi. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2012.

- "Norwegian Refugee Council homepage". Nrc.no.

- "Sphere Humanitarian Standards". Sphereproject.org.

- "Plea for 'massive aid' for Africa refugees". English.aljazeera.net. 10 July 2011.

- Gettleman, Jeffrey (3 February 2012). "U.N. Says Somalia Famine Has Ended, but Warns That Crisis Isn't Over". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- "The worst drought in 60 years in Horn Africa". Africa and Europe in Partnership. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Number of Somali refugees declining due to aid and rainfall". Pcusa.org. 5 December 2011.

- Campbell, Elizabeth H. (1 September 2006). "Urban Refugees in Nairobi: Problems of Protection, Mechanisms of Survival, and Possibilities for Integration". Journal of Refugee Studies. 19 (3): 396–413. doi:10.1093/jrs/fel011. ISSN 0951-6328.

- "Somalis in Kenya face mistrust". CS Monitor. 27 June 2014. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Horst, Cindy (15 May 2006). Transnational Nomads: How Somalis Cope with Refugee Life in the Dadaab Camps of Kenya. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9780857454386.

- Aubone, Amber; Hernandez, Juan (1 December 2013). "Assessing Refugee Camp Characteristics and The Occurrence of Sexual Violence: A Preliminary Analysis of the Dadaab Complex". Refugee Survey Quarterly. 32 (4): 22–40. doi:10.1093/rsq/hdt015. ISSN 1020-4067.

- dfava (16 September 2013). "Microfinance". CARE. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- Jahiruddin, ATM; Short, Patricia (2011). "Can Microcredit Worsen Poverty? Cases of Exacerbated Poverty in Bangladesh" (PDF). Development in Practice. 21 (8): 1109–1121. doi:10.1080/09614524.2011.607155. S2CID 154952803.

- Bateman, Milford (2010). Why Doesn't Microfinance Work?: The Destructive Rise of Local Neoliberalism. New York: Zed Books. pp. 6–59, 201–212.

- "What Microloans Miss". The New Yorker. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- "560,000 Somalis to return home following tripartite agreement". Daily Post. 12 November 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Kenya softens its position on proposed closure of Dadaab refugee camp". Goobjoog. 30 April 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- "Scapegoats". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- "Kenya loses patience over Dadaab refugee camp housing displaced Somalis". hiiraan.com. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- "2014 Statistical Yearbook". UNHCR. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "The future of the world's largest refugee camp". ISS Peace and Security Council Report. 24 August 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- "Somalia President convenes Federal Parliament". Garowe Online. 27 April 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- Agutu, Nancy (6 May 2016). "Refugees must go, Kenya says". The Star. Kenya. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- "Somalia President Raises Concern Over Plans To Shut Kenya's Dadaab Refugee Camp". CNN. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Closing the world's largest refugee camp". The Economist. 14 May 2016. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

Further reading

- Ben Rawlence (2017). City of Thorns: Nine Lives in the World's Largest Refugee Camp. Picador. ISBN 978-1250118738.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dadaab. |

- A slide show concerning camp planning, social justice, and environmental deterioration

- Collection of Dadaab Research Resources

- Photodocumentation of Dadaab Housing and Construction

- New High-Speed Network Connects Dadaab Aid Agencies For Collaboration

- High Speed Network to Connect Aid Agencies in Dadaab, Kenya