Cumulative prospect theory

Cumulative prospect theory (CPT) is a model for descriptive decisions under risk and uncertainty which was introduced by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in 1992 (Tversky, Kahneman, 1992). It is a further development and variant of prospect theory. The difference between this version and the original version of prospect theory is that weighting is applied to the cumulative probability distribution function, as in rank-dependent expected utility theory but not applied to the probabilities of individual outcomes. In 2002, Daniel Kahneman received the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel for his contributions to behavioral economics, in particular the development of Cumulative Prospect Theory (CPT).

Outline of the model

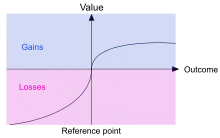

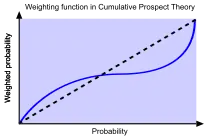

The main observation of CPT (and its predecessor prospect theory) is that people tend to think of possible outcomes usually relative to a certain reference point (often the status quo) rather than to the final status, a phenomenon which is called framing effect. Moreover, they have different risk attitudes towards gains (i.e. outcomes above the reference point) and losses (i.e. outcomes below the reference point) and care generally more about potential losses than potential gains (loss aversion). Finally, people tend to overweight extreme events, but underweight "average" events. The last point is in contrast to Prospect Theory which assumes that people overweight unlikely events, independently of their relative outcomes.

CPT incorporates these observations in a modification of expected utility theory by replacing final wealth with payoffs relative to the reference point, replacing the utility function with a value function that depends on relative payoff, and replacing cumulative probabilities with weighted cumulative probabilities. In the general case, this leads to the following formula for subjective utility of a risky outcome described by probability measure :

where is the value function (typical form shown in Figure 1), is the weighting function (as sketched in Figure 2) and , i.e. the integral of the probability measure over all values up to , is the cumulative probability. This generalizes the original formulation by Tversky and Kahneman from finitely many distinct outcomes to infinite (i.e., continuous) outcomes.

Differences from prospect theory

The main modification to prospect theory is that, as in rank-dependent expected utility theory, cumulative probabilities are transformed, rather than the probabilities themselves. This leads to the aforementioned overweighting of extreme events which occur with small probability, rather than to an overweighting of all small probability events. The modification helps to avoid a violation of first order stochastic dominance and makes the generalization to arbitrary outcome distributions easier. CPT is, therefore, an improvement over Prospect Theory on theoretical grounds.

Applications

Cumulative prospect theory has been applied to a diverse range of situations which appear inconsistent with standard economic rationality, in particular the equity premium puzzle, the asset allocation puzzle, the status quo bias, various gambling and betting puzzles, intertemporal consumption and the endowment effect.

Parameters for cumulative prospect theory have been estimated for a large number of countries,[1] demonstrating the broad validity of the theory.

References

- Rieger, M., Wang, M. & Hens, T.(2017). Estimating Cumulative Prospect Theory Parameters from an International Survey. Theory and Decision, 82, 4, 567-596.

- Tversky, Amos; Daniel Kahneman (1992). "Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty". Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 5 (4): 297–323. doi:10.1007/BF00122574.