Cultural diversity in Puerto Rico

Non-Hispanic cultural diversity in Puerto Rico (Borinquen) and the basic foundation of Puerto Rican culture began with the mixture of the Spanish, Taíno and African cultures in the beginning of the 16th century. In the early 19th century, Puerto Rican culture became more diversified with the arrival of hundreds of families from non-Hispanic countries such as Corsica, France, Germany and Ireland. To a lesser extent other settlers came from Lebanon, China, Portugal and Scotland.

| Non-Hispanic Cultural diversity in Puerto Rico | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Notable Puerto Ricans with non-Hispanic surnames | |||||||

|

| |||||||

Factors that contributed to the immigration of non-Hispanic families to Puerto Rico included the advent of the Second Industrial Revolution, and widespread crop failures in Europe. All this, plus the spread of the cholera epidemic, came at a time when desire for independence was growing among Spanish subjects of Spain's last two colonies in the Western Hemisphere, Puerto Rico and Cuba.

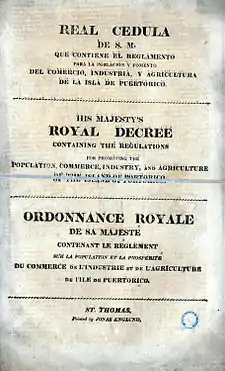

As a consequence the Spanish Crown made concessions with the establishment of the "Real Cédula de Gracias de 1815" (Royal Decree of Graces of 1815), which allowed European Catholics to settle in the island with land allotments in the interior of the island, provided they agreed to pay taxes and continue to support the Catholic Church.[1] In 1870, the Spanish Courts also passed the "Acta de Culto Condicionado" (Conditional Cult Act), a law granting the right of religious freedom to all those who wished to worship another religion other than the Catholic religion.

In Puerto Rico they adopted the local customs and intermarried with the locals. One of the consequences of the diversification of the cultures is that there are many Puerto Ricans and people of Puerto Rican descent who have non-Hispanic surnames. Puerto Rican surnames are not limited to those from Spain. Puerto Ricans commonly use both their father's and mother's surnames. It is thus not unusual to find someone with a non-Hispanic surname and a Hispanic surname. Two examples are Ramón Power y Giralt and Demetrio O'Daly y Puente. Both of these Puerto Ricans have their father's Irish surname and their mother's Spanish surname.[2]

Other factors, such as the Great Depression and World War II, contributed to the large migration of Puerto Ricans to the United States mainland. Many Puerto Ricans married with non-Hispanics and had children of Puerto Rican descent who were inscribed with non-Hispanic surnames.[2]

Since 2007, the Government of Puerto Rico has been issuing "Certificates of Puerto Rican Citizenship" to anyone born in Puerto Rico or to anyone born outside of Puerto Rico with at least one parent who was born in Puerto Rico.[3][4] Puerto Rican citizenship was first legislated by the United States Congress in Article 7 of the Foraker Act of 1900[5] and later recognized in the Constitution of Puerto Rico.[6][7] Puerto Rican citizenship existed before the U.S. takeover of the islands of Puerto Rico and continued afterwards.[6][8]

The contributions made by non-Hispanics to music, art, literature language, cuisine, religion and heritage, were instrumental in the development of modern-day Puerto Rican culture. The mixture of both the Hispanic and non-Hispanic immigrant cultures are evident in the island's political, commercial and religious structures.

First settlers

The first people from Europe to arrive in Puerto Rico were the Spanish Conquistadores. The island, called Borikén, at that time was inhabited by the Taíno Amerindians. Many Jews also known as "converso" came to Puerto Rico as members of the Spanish crews. The Jews who arrived and settled in Puerto Rico were referred to as "Crypto-Jews" or "secret Jews". When the Crypto Jews arrived on the island of Puerto Rico, they were hoping to avoid religious scrutiny, but the Inquisition followed the colonists. The Inquisition maintained "no rota" or religious court in Puerto Rico. However, heretics were written up and if necessary remanded to regional Inquisitional tribunals in Spain or elsewhere in the western hemisphere. As a result, many secret Jews settled the island's remote mountainous interior far from the concentrated centers of power in San Juan and lived quiet lives. They practiced crypto-Judaism, meaning that they secretly practiced Judaism while publicly professing to be Roman Catholic.[9]

Many Spaniards intermarried with Taínos women and much of the Taíno culture was mixed with that of the Spanish culture. Many Puerto Ricans today retain Taíno linguistic features, agricultural practices, food ways, medicine, fishing practices, technology, architecture, oral history, and religious views. Many Taíno traditions, customs, and practices have been continued.[10] The Spaniards enslaved the Taínos (the native inhabitants of the island), and many of them died as a result of Spaniards' oppressive colonization efforts. This presented a problem for Spain's royal government, which relied on slavery to staff their mining and fort-building operations. Spain's "solution": import enslaved west-Africans. The slaves were baptized by the Catholic Church and assumed the surnames of their owners.[11]

By 1570, the gold mines were declared depleted of the precious metal. After gold mining came to an end on the island, the Spanish Crown bypassed Puerto Rico by moving the western shipping routes to the north. The island became primarily a garrison for those ships that would pass on their way to or from richer colonies.[12][13]

The Africans

African free men accompanied the invading Spanish Conquistadors. The Spaniards enslaved the Taínos (the native inhabitants of the island), and many of them died as a result of Spaniards' oppressive colonization efforts. This presented a problem for Spain's royal government, which relied on slavery to staff their mining and fort-building operations. Spain's "solution": import enslaved west-Africans. As a result, the majority of the African peoples who arrived at Puerto Rico did so as a result of the slave trade from many different societies of the African continent.[13]

A Spanish edict of 1664 offered freedom and land to African people from non-Spanish colonies, such as Jamaica and St. Dominique (Haiti), who immigrated to Puerto Rico and provided a population base to support the Puerto Rican garrison and its forts. Those freemen who settled the western and southern parts of the island soon adopted the ways and customs of the Spaniards. Some joined the local militia, which fought the British in their many attempts to invade the island. The escaped African slaves kept their former masters surnames; the free Africans who had emigrated from the West Indies had European surnames from those colonists, too. Such surnames tended to be either British or French. Therefore, it was common for Puerto Ricans of African ancestry to have non-Spanish surnames.[13]

The descendants of the former African slaves became instrumental in the development of Puerto Rico's political, economic and cultural structure. They overcame many obstacles and have made their presence felt with their contributions to the island's entertainment, sports, literature and scientific institutions. Their contributions and heritage can still be felt today in Puerto Rico's art, music, cuisine, and religious beliefs in everyday life. In Puerto Rico, March 22 is known as "Abolition Day" and it is a holiday celebrated by those who live in the island.[14]

The Irish

From the 16th to the 19th century, there was considerable Irish immigration to Puerto Rico, for a number of reasons. During the 16th century many Irishmen, who were known as "Wild Geese", fled the English Army and joined the Spanish Army. Some of these men were stationed in Puerto Rico and remained there after their military service to Spain was completed.[15] During the 18th century men such as Field Marshal Alejandro O'Reilly and Colonel Tomas O'Daly were sent to the island to revamp the capital's fortifications.."[16] O'Reilly was later appointed governor of colonial Louisiana in 1769 where he became known as "Bloody O'Reilly".[17]

The Coll family played an important role in shaping Puerto Rico's politics and literature. Dr. Cayetano Coll y Toste was a historian and writer. He was the patriarch of a prominent family of Puerto Rican educators, politicians and writers. Both Coll y Toste's sons were politicians. José Coll y Cuchí was the founder of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party and Cayetano Coll y Cuchí, was a President of Puerto Rico House of Representatives.[18] His granddaughter, Isabel Cuchí Coll, was a journalist, author and the Director of the "Sociedad de Autores Puertorriqueños" (Society of Puerto Rican Authors),[19] his other granddaughter, Edna Coll, was an educator and author. She was one of the founders of the Academy of Fine Arts in Puerto Rico.[20]

Among the members of the O'Neill family whose contributions to Puerto Rican culture are evident today are Hector O'Neill, politician and Mayor[21] Ana María O'Neill an educator, author and advocate of women's rights.[22] and María de Mater O'Neill an artist, lithographer, and professor.

The French

The French immigration to Puerto Rico began as a result of economic and political conditions in places such as Louisiana (USA) and Saint-Domingue (Haiti). On the outbreak of the French and Indian War, also known as the Seven Years' War (1754-1763), between the Kingdom of Great Britain and its North American Colonies against France, many of the French settlers fled to Puerto Rico.[23] In the 1791, Saint-Domingue (Haiti) uprising, slaves were organized into an army led by the self-appointed general Toussaint Louverture and rebelled against the French. The ultimate victory of the slaves over their white masters came about after the Battle of Vertières in 1803.[24] The French fled to Santo Domingo and made their way to Puerto Rico. Once there, they settled in the western region of the island in towns such as Mayagüez. With their expertise, they helped develop the island's sugar industry, converting Puerto Rico into a world leader in the exportation of sugar.[25] French immigration from mainland France and its territories to Puerto Rico was the largest in number, second only to Spanish immigrants and today a great number of Puerto Ricans can claim French ancestry; 16 percent of the surnames on the island are either French or French-Corsican.[26]

Their influence in Puerto Rican culture is very much present and in evidence in the island's cuisine, literature and arts.[27] The contributions of Puerto Ricans of French descent such as Manuel Gregorio Tavárez, Nilita Vientós Gastón and Fermín Tangüis can be found, but are not limited to, the fields of music,[28] education [29] and science.[30]

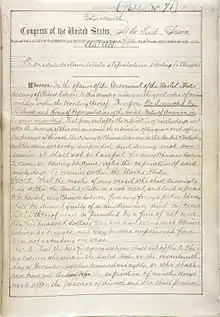

Royal Decree of Graces of 1815

By 1825, the Spanish Empire had lost all of its territories in the Americas with the exception of Cuba and Puerto Rico. These two possessions, however, had been demanding more autonomy since the formation of pro-independence movements in 1808. Realizing that it was in danger of losing its two remaining Caribbean territories, the Spanish Crown revived the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815.

The decree was printed in three languages — Spanish, English and French — intending to attract Europeans of non-Spanish origin, with the hope that the independence movements would lose their popularity and strength with the arrival of new settlers.

Under the Spanish Royal Decree of Graces, immigrants were granted land and initially given a "Letter of Domicile" after swearing loyalty to the Spanish Crown and allegiance to the Catholic Church. After five years they could request a "Letter of Naturalization" that would make them Spanish subjects. The Royal Decree, was intended for non-Hispanic Europeans and not Asians nor people that were not Christian. [1]

In 1897, the Spanish Cortés also granted Puerto Rico a Charter of Autonomy, which recognized the island's sovereignty and right to self-government. By April 1898, the first Puerto Rican legislature was elected and called to order.

Famine

Many economic and political changes occurred in Europe during the latter part of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. Hundreds of farm workers abandoned their work in agriculture and moved to the larger cities with the advent of the Second Industrial Revolution in search of better paying jobs. Those who stayed behind and attended their farmlands suffered from diseases like the cholera epidemic, and the consequences of widespread crop failure from long periods of drought and the potato fungus that caused the Great Famine of Ireland of the 1840s. Starvation was widespread in Europe. In Ireland, the famine killed over one million Irish people and created nearly two million refugees.

The Corsicans

The island of Puerto Rico is very similar in geography to the island of Corsica and therefore appealed to the many Corsicans who wanted to start a "new" life. Hundreds of Corsicans and their families immigrated to Puerto Rico from as early as 1830, and their numbers peaked in the early 1900s.[1] The first Spanish settlers settled and owned the land in the coastal areas, the Corsicans tended to settle the mountainous southwestern region of the island, primarily in the towns of Adjuntas, Lares, Utuado, Ponce, Coamo, Yauco, Guayanilla and Guánica. However, it was Yauco whose rich agricultural area attracted the majority of the Corsican settlers. The three main crops in Yauco were coffee, sugar cane and tobacco. The new settlers dedicated themselves to the cultivation of these crops and within a short period of time some were even able to own and operate their own grocery stores. However, it was with the cultivation of the coffee bean that they would make their fortunes. The descendants of the Corsican settlers were also to become influential in the fields of education, literature, journalism and politics.[31]

Today the town of Yauco is known as both the "Corsican Town" and "The Coffee Town". There's a memorial in Yauco with the inscription, "To the memory of our citizens of Corsican origin, France, who in the C19 became rooted in our village, who have enriched our culture with their traditions and helped our progress with their dedicated work - the municipality of Yauco pays them homage." The Corsican element of Puerto Rico is very much in evidence, Corsican surnames such as Paoli, Negroni and Fraticelli are common.[32]

The Germans

.jpg.webp)

German immigrants arrived in Puerto Rico from Curaçao and Austria during the early 19th century. Many of these early German immigrants established warehouses and businesses in the coastal towns of Fajardo, Arroyo, Ponce, Mayagüez, Cabo Rojo and Aguadilla. One of the reasons that these businessman established themselves in the island was that Germany depended mostly on Great Britain for such products as coffee, sugar and tobacco. By establishing businesses dedicated to the exportation and importation of these and other goods, Germany no longer had to pay England high tariffs. Not all immigrants were businessmen—some were teachers, farmers, and skilled laborers.[33]

In Germany, the European Revolutions of 1848 in the German states erupted, leading to the Frankfurt Parliament. Ultimately, the rather non-violent "revolution" failed. Disappointed, many Germans immigrated to the Americas and Puerto Rico, dubbed as the Forty-Eighters. The majority of these came from Alsace-Lorraine, Baden, Hesse, Rheinland and Württemberg.[34] German immigrants were able to settle in the coastal areas and establish their businesses in towns such as Fajardo, Arroyo, Ponce, Mayagüez, Cabo Rojo and Aguadilla. Those who expected free land under the terms of the Spanish Royal Decree, settled in the central mountainous areas of the island in towns such as Adjuntas, Aibonito and Ciales among others. They made their living in the agricultural sector and in some cases became owners of sugar cane plantations. Others dedicated themselves to the fishing industry.[35]

In 1870, the Spanish Courts passed the "Acta de Culto Condicionado" (Conditional Cult Act), a law granting the right of religious freedom to all those who wished to worship another religion other than the Catholic religion. The Anglican Church, the Iglesia Santísima Trinidad, was founded by German and English immigrants in Ponce in 1872.[35]

By the beginning of the 20th century, many of the descendants of the first German settlers had become successful businessmen, educators, and scientists and were among the pioneers of Puerto Rico's television industry. Among the successful businesses established by the German immigrants in Puerto Rico were Mullenhoff & Korber, Frite, Lundt & Co., Max Meyer & Co. and Feddersen Willenk & Co. Korber Group Inc. one of Puerto Rico's largest advertising agencies was founded by the descendants of William Korber.[36]

The Chinese

When the United States enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act on May 6, 1882, many Chinese in the United States fled to Puerto Rico, Cuba and other Latin American nations. They established small niches and worked in restaurants and laundries. The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law that suspended Chinese immigration. After the Spanish–American War, Spain ceded Puerto Rico to the United States under the conditions established by the Treaty of Paris of 1898. Chinese workers in the United States were allowed to travel to Puerto Rico. Some worked in the island's sugar industry, but most worked in re-building Puerto Rico's infrastructure and rail systems. Many of the workers in Puerto Rico decided to settle permanently in the island.

Various businesses are named "Los Chinos" (The Chinese) and a Valley in the town of Maunabo, Puerto Rico is called "Quebrada Los Chinos" (The Chinese Stream).[37] The Padmasambhava Buddhist Center, whose followers practice Tibetan Buddhism, has a branch in Puerto Rico.[38]

Post Spanish–American War

Puerto Rico was ceded by Spain to the United States at the end of the Spanish–American War in 1898. Almost immediately, the United States began the “Americanization” process of Puerto Rico. The U.S. occupation brought about a total change in Puerto Rico's economy and polity.[39] The "Americanization” process of the island had an immediate effect on the political, commercial, military and sports culture of the Puerto Ricans. Baseball, which has its origins in 18th century England and later developed in the United States, was introduced to the island by a group of Puerto Ricans and Cubans who learned the sport in the United States. The sport was also played by the American soldiers who organized games as part of their training. Puerto Ricans were also introduced to the sport of Boxing and Basketball by the occupying military forces.[40]

Many non-Hispanic soldiers who were assigned to the military bases in Puerto Rico choose to stay and live in the island. Unlike their counterparts who settled in the United States in close knit ethnic communities, these people intermarried with Puerto Ricans and adopted the language and customs of the island thereby completely integrating themselves into the society of their new homeland.[40]

The Jews

Even though the first Jews who arrived and settled in Puerto Rico were "Crypto-Jews" or "secret Jews", the Jewish community did not flourish in the island until after the Spanish–American War. Jewish-American soldiers were assigned to the military bases in Puerto Rico and many chose to stay and live on the island. Large numbers of Jewish immigrants began to arrive in Puerto Rico in the 1930s as refugees from Nazi occupied Europe. The majority settled in the island's capital, San Juan, where in 1942 they established the first Jewish Community Center of Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico is home to the largest and wealthiest Jewish community in the Caribbean with almost 3,000 Jewish inhabitants.[41] Puerto Rican Jews have made many contributions to the Puerto Rican way of life. Their contributions can be found, but are not limited to, the fields of education, commerce and entertainment. Among many successful businesses they established are Supermercados Pueblo (Pueblo Supermarkets), Almacenes Kress (clothing store), Doral Bank, Pitusa and Me Salve.[42][43][44]

Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution of 1959, influenced the large immigration of Chinese and Jews to the island. In 1959, thousands of business-minded Chinese fled Cuba, after the success Cuban Revolution led by Fidel Castro. One of the results of the communist revolution was that the state took over private property and nationalized all private-owned businesses. Most of the Cuban Chinese fled overseas and among the places where many of them settled were Puerto Rico, Miami and New York.[45] Also, almost all of Cuba's 15,000 Jews went into exile. The majority of them also fled to Miami and Puerto Rico.[46]

Puerto Rican migration to the United States

Puerto Ricans were Spanish citizens before Puerto Rico was ceded to the United States under the terms of the Treaty of Paris of 1898. After Puerto Rico was ceded, they became citizens of Puerto Rico. Before 1917, when the U.S. Congress passed the Jones-Shafroth Act, popularly called the Jones Act, which granted Puerto Ricans U.S. citizenship.[47] Puerto Ricans who moved to New York were considered immigrants. Later several factors contributed and led to what became known as "The Great Migration" of Puerto Ricans to New York. These were the following: the Great Depression, World War II and the advent of air travel.

The Great Depression that spread throughout the world also affected Puerto Rico. Since the island's economy depended and still depends on that of the United States, the failure of American banks and industries was strongly felt in the island. Unemployment rose as a consequence and many families fled to the U.S. mainland in search of jobs.[48]

The outbreak of World War II opened doors to many jobs for migrants. Since a large portion of the male population of the U.S. was sent to war, there was a sudden need for people to fill the jobs they left behind. Puerto Rican men and women found jobs in factories and ship docks, producing both domestic and warfare goods.[49]

The advent of air travel provided Puerto Ricans with an affordable and faster way of travel to New York. Eventually some Puerto Ricans adopted the mainland United States as their home and married with non-Hispanics. Their children were of Puerto Rican descent who were inscribed with non-Hispanic surnames.[49]

Puerto Ricans with non-Hispanic surnames

The cultural impact immigrants from non-Hispanic countries have made in Puerto Rico is also apparent in the non-Hispanic surnames of many Puerto Ricans and people of Puerto Rican descent.[2] The following is a list solely of Puerto Ricans or people of Puerto Rican descent with non-Hispanic surnames and is not intended to reflect the ethnicity of the person listed. This list also includes people of Puerto Rican and non-Hispanic descent born in the United States and non-Hispanic men/women who adopted Puerto Rico as their homeland as well.[note 1]

| Notable Puerto Ricans and people of Puerto Rican descent with non-Hispanic surnames. | ||||

|

Chinese origin

Corsican-Italian origin

Czech origin

French origin

German origin

|

(German origin - continued)

Irish-English origin

Jewish origin

|

Note

- References of those listed with articles can be found within wikilinks to the subjects article. Notable Puerto Ricans or people of Puerto Rican descent listed without an article have a reference next to their name.

See also

References

- Archivo General de Puerto Rico: Documentos Archived October 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved August 3, 2007

- "Mainland Passage: The Cultural Anomaly of Puerto Rico"; by: Ramon E. Soto-Crespo; Publisher: Univ of Minnesota Press; ISBN 0816655871; ISBN 978-0816655878

- (Spanish) Citizenship application. Puerto Rico Department of State

- Departamento de Estado expedirá certificados de ciudadanía puertorriqueña

- Puerto Rican Immigrants: A Resource Guide for Teachers and Students. Warren Stevenson, Joshua Romano, Kaitlin Quinn-Stearns, and Thomas Kennedy. Fitchburg State University. Immigration and the American Identity, Dr. Laura Baker. TAH Program. Summer 2009. Page 2. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- "LEY FORAKER DEL 1900 DE PUERTO RICO EN LEXJURIS.COM". www.lexjuris.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2011-07-31. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- (Spanish) 97 DTS 135 -- Ramírez de Ferrer v. Mari Brás

- Puerto Rico: Hearing before the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. US Senate. 109th Congress, 2nd Session on The Report by the President's Task Force on Puerto Rico's Status. Nov 15, 2006. page 114.

- Vazquez, Larizza (December 8, 2000). "Los Judios en Puerto Rico". El Nuevo Dia (in Spanish). Archived from the original on October 14, 2008.

- Taliman, Valerie. Taíno Nation alive and strong. Indian Country Today. 24 Jan 2001. Retrieved 24 Sept 2009.

- Bartolomé de las Casas. Oregon State University Archived 2002-12-26 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- The First West African on St. Croix? Archived 2012-02-17 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- African Aspects of the Puerto Rican Personality by (the late) Dr. Robert A. Martinez, Baruch College. (Archived from the original on July 20, 2007)

- Encyclopedia of Days Archived August 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved August 8, 2007

- "Irish and Scottish Military Migration to Spain". Trinity College Dublin. 2008-11-29. Retrieved 26 May 2008.

- "The Celtic Connection". Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- Alejandro O'Reilly 1725–1794 Archived 2008-12-05 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved November 29, 2008

- El Nuevo Dia 3 Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "Figuras Historicas De Puerto Rico, Vol. 2” ; Eitor: Adolfo R. Lopez; Page 5 and 6; 2000. Publisher: Editorial Codillera, Inc.; ISBN 0-88495-188-X.

- "Tras las Huellas de Nuestro Paso"; by: Ildelfonso López; Publisher: AEELA, 1998

- Héctor O'Neill repasa su trayectoria en Guaynabo

- Biografias Archived July 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Historical Preservation Archive: Transcribed Articles & Documents

- Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Biography and Autobiography by J. R. Beard, 1863

- "The Haitian Revolution". Archived from the original on 2007-08-09. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- Corsican immigration to Puerto Rico Archived 2007-10-28 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved July 31, 2007

- Preserving our traditional Puerto Rican cuisine

- Manuel Gregorio Tavarez. Archived 2013-12-30 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopedia Puerto Rico. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- Women, Creole Identity, and Intellectual Life in Early Twentieth-Century Puerto Rico; By Magali Roy-Féquière, Juan Flores, Emilio Pantojas-García; Published by Temple University Press, 2004; ISBN 1-59213-231-6, ISBN 978-1-59213-231-7

- Los Primeros años de Tangüis Archived 2008-02-18 at the Wayback Machine

- "Corsican immigration to Puerto Rico". Archived from the original on 2007-10-28. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- Corsican Immigrants to Puerto Rico, retrieved July 31, 2007

- Dr. Ursula Acosta: Genealogy: My Passion and Hobby

- [Breunig, Charles (1977), The Age of Revolution and Reaction, 1789 - 1850 (ISBN 0-393-09143-0)]

- La Presencia Germanica en Puerto Rico

- Group

- Quebrada Los Chinos Archived July 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Budda Net

- Safa, Helen (March 22, 2003). "Changing forms of U.S. hegemony in Puerto Rico: the impact on the family and sexuality". Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- Primera Hora newspaper; "Eran otros tiempos"; by: Alex Figueroa Cancel, July 20, 2008

- The Virtual Jewish History Tour Puerto Rico, Jewish Virtual Library, Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- Toppel, 84, supermarket mogul, philanthropist, Palm Beach Post, Retrieved January 9, 2009

- Puerto Rico Companies Archived 2005-05-03 at the Wayback Machine, Right Management, Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- Work hard and improve constantly. (Israel Kopel, president of Almacenes Pitusa) (Top 10 Business Leaders of Puerto Rico: 1991), Caribbean Business, Retrieved January 9, 2009

- Tung, Larry (June 2003). "Cuban Chinese Restaurants". Gotham Gazette. Retrieved September 14, 2008.

- Luxner, Larry, "Puerto Rico's Jews planting roots on an island with little Jewish history" Archived 2005-11-07 at the Wayback Machine, Luxner News, Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- Levinson, Sanford; Sparrow, Bartholomew H. (2005). The Louisiana Purchase and American Expansion: 1803–1898. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 166, 178.

U.S. citizenship was extended to residents of Puerto Rico by virtue of the Jones Act, chap. 190, 39 Stat. 951 (1971)(codified at 48 U.S.C. § 731 (1987)

- Great Depressions of the Twentieth Century, edited by T. J. Kehoe and E. C. Prescott

- "LAS WACS"-Participacion de la Mujer Boricua en la Seginda Guerra Mundial; by: Carmen Garcia Rosado; page 60; 1ra. Edicion publicada en Octubre de 2006; 2da Edicion revisada 2007; Regitro tro Propiedad Intectual ELA (Government of Puerto Rico) #06-13P-)1A-399; Library of Congress TXY 1-312-685.

- Vancouver welcomes the world

- NY Daily News Juan Manuel Garcia Passalacqua

- Puerto Rico Herald

- "US Department of Housing and Urban Development" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-02. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- Lajas

- WAPA

- "Protagonistas de nuestra historia". Archived from the original on 2010-11-16. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- New York Times

- "Puerto Rican Nationalist Party". Archived from the original on 2016-03-06. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- "Estadio Juan Ramón Loubriel - Bayamón, Puerto Rico" (in Spanish). Puerto Rico Islanders. 2008-08-23. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- Joaquin Mouliert

- Surgery at the Service of Theology.

- Souffront, Evelyn

- GOVERNMENT DEVELOPMENT BANK FOR PUERTO RICO

- Korber House

- Noticieros

- Gran tributo a Orvil Miller

- Dictionary of Literary Biography intro online

- Heath Anthology bio

- Pacific News Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine

- 82 Sigma Convención. Puerto Rico: Fi Sigma Alfa. October 2010. p. 7.

- Fallece Waldemar Schmidt

- 1974 Miss Universe Beauty Pageant

- Fernández-Marina, Ramón (2006). "CULTURAL STRESSES AND SCHIZOPHRENOGENESIS IN THE MOTHERING-ONE IN PUERTO RICO". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 84: 864–877. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb39120.x.

- German Surnames - Meanings & Origins

- Puerto Rico Herald

- Narrativa Cuento y Novela

- Gente de Arecibo

- Cruz Monclova, Lidio, Historia de Puerto Rico en el Siglo XIX, 3 vols., Ed. U.P.R., Río Piedras, 1958; 1972; 1974)

- American Idol: Scotty McCreey Called "True Artist" by Jennifer Lopez, Confirms Puerto Rican Heritage from Fox News 5 May 2011

- prpop Puerto Rico Popular Culture Sharon Riley

- 1986 Miss Universe Pageant

- Paul Rober Walker (1988). "The way of the Jibaro". Pride of Puerto Rico: The life of Roberto Clemente. United States: Harcourt Brace & Company. p. 3. ISBN 0-15-307557-0.

Roberto's father, Don Melchor Clemente, worked as foreman in the sugar fields.

- Puerto Rico Popular Culture

- "The Ballplayers - Bernie Williams Biography". BaseballLibrary.com. Archived from the original on 2008-12-27. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- Hedgebrook Archived July 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Komix

- Reflections on the Centenary of the United States' Acquisition of Puerto Rico Archived 2012-10-20 at the Wayback Machine, Yale University, Retrieved January 9, 2009

- Levins Morales Blog: http://www.historica.us

- The Show Must Go on: How the Deaths of Lead Actors Have Affected Television By Douglas Snauffer, Joel Thurm. McFarland press. p. 74.

- "Freddie Prinze Jr . com". Freddieprinzejr.com. Archived from the original on 2010-03-08. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- highest-ranking Latina in network television

- Antimusic - Singled out:Ra