Counter-recruitment

Counter-recruitment refers to activity opposing military recruitment, in some or all of its forms. Among the methods used are research, consciousness-raising, political advocacy and direct action. Most such activity is a response to recruitment by state armed forces, but may also target intelligence agencies, private military companies, and non-state armed groups.

Rationale

The rationale for counter-recruitment activity may be based on any of the following reasons:

- The view that war is immoral - see pacifism.

- The view that some or all military organizations are a tool of imperialism - see anti-imperialism.

- Evidence from Australia,[1] Canada,[2] France,[3][4] the UK,[5][6] and the US[7][8] that abusive behaviour such as bullying, racism, sexism and sexual violence, and homophobia are common in military organizations - see, for example, Women in the military and Sexual orientation and gender identity in military service.

- Evidence from the UK[9][10][11][12][13][14] and US[15][16][17][18][19] that military training and employment lead to higher rates of mental health and behavioural problems than are usually found in civilian life, particularly after personnel have left the armed forces.

- Evidence from Germany,[20] Israel,[21] the UK,[22][5][23][24] the US[25][26][27][28][29] and elsewhere that recruiting practices sanitise war, glorify the role of military personnel, and obscure the risks and obligations of military employment, thereby misleading potential recruits, particularly adolescents from socio-economically deprived backgrounds.

- Evidence from Germany,[20] the UK,[30][5][22] the US[31] and elsewhere[32][33] that recruiters target, and capitalise on the precarious position of, socio-economically deprived young people as potential recruits, in a phenomenon sometimes called the poverty draft.

- The fact that military employment suspends certain fundamental rights and freedoms (such as freedom of association and freedom of speech) and introduces new offences with heavy penalties, such as absence without leave (AWOL) (see, for example, Offences against military law in the United Kingdom).[34]

- The fact that some armed forces rely on children aged 16 or 17 to fill their ranks, and evidence from Australia,[35] Israel,[36] the UK[23][37][38][39][40][24] and from the Vietnam era in the US[41][42][43] that these youngest recruits are most likely to be adversely affected by the demands and risks of military life.

Armed forces spokespeople have defended the status quo by recourse to the following:

Activity

Examples of counter-recruitment activity are:

- Research and analysis of military recruitment practices, and of the effects and outcomes of military employment.[26][5][22][23][46][24][40][33][32]

- Legal advocacy (aimed at changing legislation) and political advocacy (aimed at changing policy) to regulate or limit the scope of military recruitment.[45][47]

- Consciousness-raising to raise awareness and concern about military recruitment practices and the effects of military training and employment.[48][49][50]

- Providing information to potential recruits about the risks and obligations of enlistment,[51][52] or discouraging enlistment.[53]

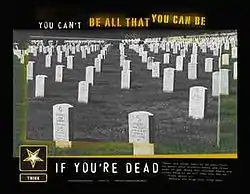

- Satirising the propagandistic glorification of military personnel.[54]

In the United States

Counter-recruitment (which has long been a strategy of pacifist and other anti-war groups) received a boost in the United States with the unpopularity of the war in Iraq and brief recruitment difficulties of branches of the U.S. military, particularly the Army; although the Army has met, or exceeded, its recruitment goals year after year during that period. Beginning in early 2005, the U.S. counter-recruitment movement grew, particularly on high school and college campuses, where it is often led by students who see themselves as targeted for military service in a war they do not support.

Early history

The counter-recruitment movement was the successor to the anti-draft movement with the end of conscription in the United States in 1973, just after the end of the Vietnam War. The military increased its recruiting efforts, with the total number of recruiters, recruiting stations, and dollars spent on recruiting each more than doubling between 1971 and 1974.[55] Anti-war and anti-draft activists responded with a number of initiatives, using tactics similar to those used by counter-recruiters today. Activists distributed leaflets to students, publicly debated recruiters, and used equal-access provisions to obtain space next to recruiters to dispute their claims. The American Friends Service Committee (A.F.S.C.) and the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors (C.C.C.O.) began publishing counter-recruitment literature and attempting to coordinate the movement nationally. These organizations have been continuously involved in counter-recruitment to the present day.[56]

High schools

Most counter-recruitment work in the U.S. is focused at the policy level of public school systems. This work is generally done by parents and grandparents of school-aged children, and the most common activity is information and advocacy with school officials (principals, school boards, etc.) and with the general population in their local school area. CR at the K12 level is categorically different from other movements, since most of the students are underaged minors and parents are their legal custodians and guardians, not the schools.

The most common policy goal is that the frequency of military recruiters' visits to public schools, their locations in schools, and their types of activities be controlled rather than unlimited. Many of the larger urban school districts have implemented such guidelines since 2001.

Other goals have included "truth in recruiting", that counselors or curriculum elements be implemented to address the deficiency in high school students' understanding of war and the military life, rather than allowing military recruiters to perform that role.

On high school campuses, counter-recruitment activists since 2001 have also focused around a provision of the No Child Left Behind Act, which requires that high schools provide contact and other information to the military for all of their students who do not opt out.

Counter-recruitment campaigns have attempted to change school policy to ban recruiters regardless of the loss of federal funds, to be active about informing students of their ability to opt out, and/or to allow counter-recruiters access to students equal to the access given to military recruiters. These political campaigns have had some success, particularly in the Los Angeles area, where one has been led by the Coalition Against Militarism in Our Schools, and the San Francisco Bay Area. A simpler and easier, though perhaps less effective, strategy by counter-recruiters has been to show up before or after the school day and provide students entering or exiting their school with opt-out forms, produced by the local school district or by a sympathetic national legal organization such as the American Civil Liberties Union or the National Lawyers Guild.

Organizations which have attempted to organize such campaigns on a national scale include A.F.S.C. and C.C.C.O., the Campus Antiwar Network (C.A.N.), and the War Resisters League. Code Pink, with the Ruckus Society, has sponsored training camps on counter-recruitment as well as producing informational literature for use by counter-recruiters. United for Peace and Justice has counter-recruitment as one of its seven issue-specific campaigns. Mennonite Central Committee[57] is another resource on the subject. Some of these organizations focus on counter-recruitment in a specific sector, such as high schools or colleges, while the National network Opposing the Militarization of Youth,[58] founded in 2004, deals with the larger issue of militarism as it affects young people and society.

In Canada

In response to the Canadian Forces' role as a member of the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan, an anti-war movement developed in Canada which has tried to utilize counter-recruitment as a part of its efforts. In particular, Operation Objection emerged as the umbrella counter-recruitment campaign in Canada.[59] Operation Objection claimed to have active counter-recruitment operations in 8 to 10 Canadian cities.[60] However, coordinated attempts at counter-recruitment activism in Canada have been fairly limited as of late, and for the most part, unsuccessful.

In the 2005–06 academic year at York University, the York Federation of Students, a federation representing ten of the university's student unions, clashed with a Canadian Forces recruiter forcibly removing the recruiter and the kiosk from the Student Center. York University maintains that the Canadian Forces have the same right to recruit as any other employer participating in career fairs on campus.[61]

On October 25, 2007, an attempt by the student union at the University of Victoria to ban Canadian Forces from participating in career fairs on campus failed when the student body voted overwhelmingly in favour of allowing the Canadian military to participate in recruitment and career development activities available to students. Approximately 500 students, five times the usual attendance, appeared at the Annual General Meeting of the University of Victoria Students' Society (UVSS), and voted to defeat the motion proposed to stop the Canadian Forces from appearing on campus at career development events, with an estimated 25 votes in favour of the ban. Those voting against the ban argued that the ban was a restriction on freedom of choice and an infringement of students' free speech, that it went beyond the mandate of student government, and that student union executives should not be advocating policy that does not reflect the views of the fee-paying student body.[62][63][64][65]

In November 2007, the Minister of Education for Prince Edward Island, Gerard Greenan, was requested by the Council of Canadians to ban military recruitment on PEI campuses. The Minister responded that military service "is a career and... we think its right to let the Armed Forces have a chance to present this option to students."[66]

See also

References

- Defence Abuse Response Taskforce (2016). "Defence Abuse Response Taskforce: Final report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-13. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

- Canada, Statcan [official statistics agency] (2016). "Sexual Misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces, 2016". www.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2017-12-11.

- Leila, Miñano; Pascual, Julia (2014). La guerre invisible: révélations sur les violences sexuelles dans l'armée française (in French). Paris: Les Arènes. ISBN 978-2352043027. OCLC 871236655.

- Lichfield, John (2014-04-20). "France battles sexual abuse in the military". Independent. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

- Gee, D (2008). "Informed Choice? Armed forces recruitment practices in the United Kingdom". Archived from the original on 2017-12-13. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- UK, Ministry of Defence (2015). "British Army: Sexual Harassment Report" (PDF). Retrieved 2017-12-11.

- Marshall, A; Panuzio, J; Taft, C (2005). "Intimate partner violence among military veterans and active duty servicemen". Clinical Psychology Review. 25 (7): 862–876. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.009. PMID 16006025.

- US, Department of Defense (2017). "Department of Defense Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military: Fiscal Year 2016" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-08. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- MacManus, Deirdre; Rona, Roberto; Dickson, Hannah; Somaini, Greta; Fear, Nicola; Wessely, Simon (2015-01-01). "Aggressive and Violent Behavior Among Military Personnel Deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: Prevalence and Link With Deployment and Combat Exposure". Epidemiologic Reviews. 37 (1): 196–212. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxu006. ISSN 0193-936X. PMID 25613552.

- Goodwin, L.; Wessely, S.; Hotopf, M.; Jones, M.; Greenberg, N.; Rona, R. J.; Hull, L.; Fear, N. T. (2015). "Are common mental disorders more prevalent in the UK serving military compared to the general working population?". Psychological Medicine. 45 (9): 1881–1891. doi:10.1017/s0033291714002980. ISSN 0033-2917. PMID 25602942.

- MacManus, Deirdre; Dean, Kimberlie; Jones, Margaret; Rona, Roberto J; Greenberg, Neil; Hull, Lisa; Fahy, Tom; Wessely, Simon; Fear, Nicola T (2013). "Violent offending by UK military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: a data linkage cohort study". The Lancet. 381 (9870): 907–917. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60354-2. PMID 23499041. S2CID 606331.

- Thandi, Gursimran; Sundin, Josefin; Ng-Knight, Terry; Jones, Margaret; Hull, Lisa; Jones, Norman; Greenberg, Neil; Rona, Roberto J.; Wessely, Simon (2015). "Alcohol misuse in the United Kingdom Armed Forces: A longitudinal study". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 156: 78–83. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.033. PMID 26409753.

- Buckman, Joshua E. J.; Forbes, Harriet J.; Clayton, Tim; Jones, Margaret; Jones, Norman; Greenberg, Neil; Sundin, Josefin; Hull, Lisa; Wessely, Simon (2013-06-01). "Early Service leavers: a study of the factors associated with premature separation from the UK Armed Forces and the mental health of those that leave early". European Journal of Public Health. 23 (3): 410–415. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cks042. ISSN 1101-1262. PMID 22539627.

- Jones, M.; Sundin, J.; Goodwin, L.; Hull, L.; Fear, N. T.; Wessely, S.; Rona, R. J. (2013). "What explains post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in UK service personnel: deployment or something else?". Psychological Medicine. 43 (8): 1703–1712. doi:10.1017/s0033291712002619. ISSN 0033-2917. PMID 23199850. S2CID 21097249.

- Hoge, Charles W.; Castro, Carl A.; Messer, Stephen C.; McGurk, Dennis; Cotting, Dave I.; Koffman, Robert L. (2004-07-01). "Combat Duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, Mental Health Problems, and Barriers to Care". New England Journal of Medicine. 351 (1): 13–22. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.376.5881. doi:10.1056/nejmoa040603. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 15229303.

- Friedman, M. J.; Schnurr, P. P.; McDonagh-Coyle, A. (June 1994). "Post-traumatic stress disorder in the military veteran". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 17 (2): 265–277. doi:10.1016/S0193-953X(18)30113-8. ISSN 0193-953X. PMID 7937358.

- Bouffard, Leana Allen (2016-09-16). "The Military as a Bridging Environment in Criminal Careers: Differential Outcomes of the Military Experience". Armed Forces & Society. 31 (2): 273–295. doi:10.1177/0095327x0503100206. S2CID 144559516.

- Merrill, Lex L.; Crouch, Julie L.; Thomsen, Cynthia J.; Guimond, Jennifer; Milner, Joel S. (August 2005). "Perpetration of severe intimate partner violence: premilitary and second year of service rates". Military Medicine. 170 (8): 705–709. doi:10.7205/milmed.170.8.705. ISSN 0026-4075. PMID 16173214.

- Elbogen, Eric B.; Johnson, Sally C.; Wagner, H. Ryan; Sullivan, Connor; Taft, Casey T.; Beckham, Jean C. (2014-05-01). "Violent behaviour and post-traumatic stress disorder in US Iraq and Afghanistan veterans". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 204 (5): 368–375. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.113.134627. ISSN 0007-1250. PMC 4006087. PMID 24578444.

- Germany, Bundestag Commission for Children's Concerns (2016). Opinion of the Commission for Children's Concerns on the relationship between the military and young people in Germany.

- New Profile (2004). "The New Profile Report on Child Recruitment in Israel" (PDF). Retrieved 2017-12-10.

- Gee, D; Goodman, A. "Army visits London's poorest schools most often" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-05-29. Retrieved 2017-12-10.

- Gee, D (2017). "The First Ambush? Effects of army training and employment" (PDF). Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- Gee, David; Taylor, Rachel (2016-11-01). "Is it Counterproductive to Enlist Minors into the Army?". The RUSI Journal. 161 (6): 36–48. doi:10.1080/03071847.2016.1265837. ISSN 0307-1847. S2CID 157986637.

- Hagopian, Amy; Barker, Kathy (2011-01-01). "Should We End Military Recruiting in High Schools as a Matter of Child Protection and Public Health?". American Journal of Public Health. 101 (1): 19–23. doi:10.2105/ajph.2009.183418. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3000735. PMID 21088269.

- American Public Health Association (2012). "Cessation of Military Recruiting in Public Elementary and Secondary Schools". www.apha.org. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- "Soldiers of Misfortune: Abusive U.S. Military Recruitment and Failure to Protect Child Soldiers". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- Diener, Sam; Munro, Jamie (June–July 2005). "Military Money for College: A Reality Check". Peacework. Archived from the original on 2006-10-11.

- "Amid Scandal, Recruitment Halts". CBS News. 2005-05-20.

- Morris, Steven (2017-07-09). "British army is targeting working-class young people, report shows". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- Segal, D R; et al. (1998). "The all-volunteer force in the 1970s". Social Science Quarterly. 72 (2): 390–411. JSTOR 42863796.

- Brett, Rachel, and Irma Specht. Young Soldiers: Why They Choose to Fight. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2004. ISBN 1-58826-261-8

- "Machel Study 10-Year Strategic Review: Children and conflict in a changing world". UNICEF. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- UK, Ministry of Defence (2017). "Queen's Regulations for the Army (1975, as amended)" (PDF). Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- Australia, Department of Defence (2008). "Defence Instructions General: Management and administration of Australian Defence Force members under 18 years of age" (PDF). Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- Milgrom, C.; Finestone, A.; Shlamkovitch, N.; Rand, N.; Lev, B.; Simkin, A.; Wiener, M. (January 1994). "Youth is a risk factor for stress fracture. A study of 783 infantry recruits". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 76 (1): 20–22. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.76B1.8300674. ISSN 0301-620X. PMID 8300674.

- UK, Ministry of Defence (2017). "UK armed forces suicide and open verdict deaths: 2016". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- Blacker, Sam D.; Wilkinson, David M.; Bilzon, James L. J.; Rayson, Mark P. (March 2008). "Risk factors for training injuries among British Army recruits". Military Medicine. 173 (3): 278–286. doi:10.7205/milmed.173.3.278. ISSN 0026-4075. PMID 18419031.

- Kapur, Navneet; While, David; Blatchley, Nick; Bray, Isabelle; Harrison, Kate (2009-03-03). "Suicide after Leaving the UK Armed Forces —A Cohort Study". PLOS Medicine. 6 (3): e1000026. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000026. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 2650723. PMID 19260757.

- Gee, D and Goodman, A (2013). "Young age at Army enlistment is associated with greater war zone risks: An analysis of British Army fatalities in Afghanistan". www.forceswatch.net. Retrieved 2017-12-13.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Knapik; et al. (2004). "A review of the literature on attrition from the military services: Risk factors for attrition and strategies to reduce attrition". Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- King, D. W.; King, L. A.; Foy, D. W.; Gudanowski, D. M. (June 1996). "Prewar factors in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: structural equation modeling with a national sample of female and male Vietnam veterans". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 64 (3): 520–531. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.64.3.520. ISSN 0022-006X. PMID 8698946.

- Schnurr, Paula P.; Lunney, Carole A.; Sengupta, Anjana (April 2004). "Risk factors for the development versus maintenance of posttraumatic stress disorder". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 17 (2): 85–95. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.538.7819. doi:10.1023/B:JOTS.0000022614.21794.f4. ISSN 0894-9867. PMID 15141781. S2CID 12728307.

- Hansard (2016). "Armed Forces Bill 2016 (col. 1211)". hansard.parliament.uk. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- Hansard (2016). "Armed Forces Bill 2016 (col. 1210)". hansard.parliament.uk. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- Gee, D (2013). "The Last Ambush? Aspects of mental health in the British armed forces" (PDF). www.forceswatch.net. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- Child Soldiers International (2017). "The British armed forces: Why raising the recruitment age would benefit everyone". Child Soldiers International. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- Veterans For Peace Greater Seattle, Chapter 92. "Counter Recruiting Action Team". www.vfp92.org. Archived from the original on 2019-07-11. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- "ABOUT". Veterans For Peace UK. 2016-11-21. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- ForcesWatch (2017). "Take Action on Militarism". Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- - The National Network Opposing the Militarization of Youth (NNOMY) (2016). "Considering Enlisting?". nnomy.org. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- Before You Sign Up (2017). "Joining the army". beforeyousignup.info. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- Veterans for Peace UK (2017). "Don't Join the Army". Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- Cullen, D (2015). "Action Man: Battlefield Casualties – A Veterans for Peace UK film". Action Man: Battlefield Casualties. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- Cortright, David (2005). Soldiers in Revolt. Haymarket Books. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-931859-27-1.

- Cortright, David (2005). Soldiers in Revolt. Haymarket Books. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-931859-27-1.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-07-16. Retrieved 2013-06-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "• Home Page - the National Network Opposing the Militarization of Youth (NNOMY)".

- "Canadian Forces Operations in Afghanistan". dnd.ca. Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- http://www.themanitoban.com/2006-2007/1004/102.Operation.objection.is.a.lie.org. Retrieved November 21, 2007. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Archived May 6, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Carson Jerema (2007-10-29). "Students say let the military recruit". Macleans.ca. Archived from the original on 2011-05-18. Retrieved 2010-11-24.

- Colonist, Times (2007-10-26). "UVic students overturn military recruitment ban". Canada.com. Archived from the original on 2012-11-04. Retrieved 2010-11-24.

- "Canadian Forces Ban Vote at the UVSS AGM". YouTube. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2010-11-24.

- Archived November 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Recruit away in P.E.I. schools". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2012-09-12. Retrieved 2010-11-24.

External links

- The 2004 Official US Military School Recruiting Program Handbook

- Mennonite Central Committee

- National Network Opposing the Militarization of Youth, founded in 2004, deals with the larger issue of militarism as it affects young people.

- Hagopian, A.; Barker, K. (2011). "Should we end military recruiting in high schools as a matter of child protection and public health?". American Journal of Public Health. 101 (1): 19–23. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.183418. PMC 3000735. PMID 21088269.