Cosmos (Humboldt book)

Cosmos: A Sketch of a Physical Description of the Universe (in German Kosmos – Entwurf einer physischen Weltbeschreibung) is an influential treatise on science and nature written by the German scientist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt. Cosmos began as a lecture series delivered by Humboldt at the University of Berlin, and was published in five volumes between 1845 and 1862 (the fifth was posthumous and completed based on Humboldt's notes). In the first volume of Cosmos, Humboldt paints a general “portrait of nature”, describing the physical nature of outer space and the Earth. In the second volume he describes the history of science.[1]

Widely read by academics and laymen, Cosmos applied the ancient Greek view of the orderliness of the cosmos (the harmony of the universe) to the Earth, suggesting that universal laws applied as well to the apparent chaos of the terrestrial world. Humboldt suggests that when one contemplates the beauty of the cosmos, one can obtain personal inspiration and a beneficial, if subjective, awareness about life.[2]

Cosmos was influenced by Humboldt's various travels and studies, but mainly by his journey throughout the Americas. As he wrote, “it was the discovery of America that planted the seed of the Cosmos.”[3] Due to all of his experience in the field, Humboldt was preeminently qualified for the task to represent the universe in a single work.[1] He had extensive knowledge of many fields of learning, varied experiences as a traveler, and the resources of the scientific and literary world at his disposal.[1]

Cosmos was highly popular when it was released, with the first volume selling out in two months, and the work translated into most European languages.[4] Although the natural sciences have diverged from the romantic perspective Humboldt presented in Cosmos, the work is still considered to be a substantial scientific and literary achievement, having influenced subsequent scientific progress and imparted a unifying perspective to the studies of science, nature, and mankind.[4]

Background and influences

Since the early years of the nineteenth century, Humboldt had been a world-famous figure, second in renown only to Napoleon. As the son of an aristocratic family in Prussia, he received the best education available at the time in Europe, studying under famous thinkers at the universities of Frankfurt and Göttingen. By the time he wrote Cosmos, Humboldt was an esteemed explorer, cosmographer, biologist, diplomat, engineer, and citizen of the world.[1] While considered a geographer, he is accredited with contributing to most of the sciences of the natural world environment found today.[5]

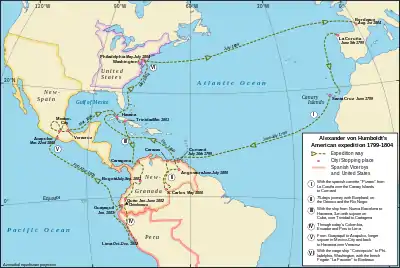

Humboldt in the Americas

Probably more than any other factor, Humboldt's career was shaped by his travels in South and Central America in the five years from 1799 to 1804.[1] Humboldt said that his Cosmos was born on the slopes of the Andes.[3] Beginning in Venezuela, he explored the Orinoco and upper Amazon valleys, climbed Mount Chimborazo in Ecuador — then believed to be the world's highest mountain — investigated changing vegetation from the tropical jungles to the top of the Andes, collected thousands of plant specimens, and accumulated a vast collection of animals, insects, and geological fragments.[1] From the notes he gathered on this journey, Humboldt was able to produce at least thirty volumes based on his observations.[4] His studies related to many scientific fields, including botany, zoology, geology, and geography, as well as narratives of popular travel and discussions of political, economic, and social conditions.[1]

Humboldt in Asia

Twenty-five years after his exploration of the Americas, at the age of sixty, Humboldt undertook an extended tour, subsidized by the Tsar of Russia, into the interior of Asia.[1] Between May and November 1829, Humboldt and his two subordinates, C.G. Ehrenberg and Gustav Rose, traveled across the vast expanse of the Russian empire. Upon his return, Humboldt left the publication of the scientific results to Ehrenberg and Rose, while his own work — a three-volume descriptive geography entitled Asie Centrale — did not appear until many years later. This work was very modest in comparison to Humboldt's South American publications. Asie Centrale focused on the facts and figures of Central Asian geography, along with data to complete his isothermal world map.[4] It was during his South American and Asian explorations that Humboldt made the observations crucial to forming his physical description of the universe in Cosmos.[1]

Berlin lectures

In 1827, having spent himself into poverty publishing his scientific works, his king, Friedrich Wilhelm III, reminded Humboldt of his debt and recalled him to Berlin. When he arrived in Berlin, Humboldt announced that he would give a course of lectures on physical geography. From November 1827 to April 1828, he delivered a series of sixty-one lectures at the University of Berlin. The lectures were so well-attended that Humboldt soon announced a second series, which was held in a music hall before an audience of thousands, free to all comers.[3] Beginning in 1828, Humboldt finally gave expression to his concept in his Berlin lectures, and from then on he labored to produce his physical description of the universe in book form.[4] Collaborators pledged to his assistance included the greatest scientists of his generation, including leaders in chemistry, astronomy, anatomy, mathematics, mineralogy, botany, and other areas of study.[1]

Publication

In 1828 after the Berlin lectures, Humboldt began formulating his vision in writing. His factual text, heavily loaded with footnotes and references, was sent in proof sheets to all the various specialists for comments and corrections before publication. In this way, he aimed to ensure that what he wrote was both accurate and up-to-date. He continually looked to his friend and literary advisor Varnhagen von Ense for advice in the matter of his style of writing.[4] In total Cosmos took twenty-five years to write.[5]

Humboldt felt as if publishing Cosmos was a race against death. The first volume was published in 1845 when he was seventy-six, the second when he was seventy-eight, the third when he was eighty-one, and the fourth when he was eighty-nine. The fifth volume, however, was only half-written when Humboldt died in 1859 and had to be completed from his notes and provided with an index over a thousand pages long.[4]

Content

Humboldt viewed the world as what the ancient Greeks called a kosmos – “a beautifully ordered and harmonious system” – and coined the modern word “cosmos” to use as the title of his final work.[6] This title allowed him to encompass heaven and Earth together.[3] He reintroduced Cosmos as “the assemblage of all things in heaven and earth, the universality of created things constituting the perceptible world.”[7] His basic purpose is outlined in the introduction to the first volume:

"The most important aim of all physical science is this: to recognize unity in diversity, to comprehend all the single aspects as revealed by the discoveries of the last epochs, to judge single phenomena separately without surrendering their bulk, and to grasp Nature's essence under the cover of outer appearances."[1]

Humboldt soon adds that Cosmos signifies both the “order of the world, and adornment of this universal order.”[7] Thus, there are two aspects of the Cosmos, the “order” and the “adornment.” The first refers to the observed fact that the physical universe, independently of humans, demonstrates regularities and patterns that we can define as laws. Adornment, however, is up to human interpretation. To Humboldt, Cosmos is both ordered and beautiful, through the human mind.[3] He created a dynamic picture of the universe that would continually grow and change as human conceptions of nature and the depth of human feeling about nature enlarge and deepen.

To represent this double-sided aspect of Cosmos, Humboldt divided his book into two parts, with the first painting a general “portrait of nature.”[1] Humboldt first examines outer space – the Milky Way, cosmic nebulae, and planets – and then proceeds to the Earth and its physical geography; climate; volcanoes; relationships among plants, animals, and mankind; evolution; and the beauty of nature. In the second part, on the history of science, Humboldt aims to take the reader on an inner or “subjective” journey through the mind.[1] Humboldt is concerned with “the difference of feeling excited by the contemplation of nature at different epochs,” that is, the attitudes toward natural phenomena among poets, painters, and students of nature through the ages.[3] The final three volumes are devoted to a more detailed account of scientific studies in astronomy, the Earth's physical properties, and geological formations.[1] On the whole, the final work followed the scheme of the Berlin lectures reasonably faithfully.[4]

In the book Humboldt provided observations supporting the elevation crater theory of his friend Leopold von Buch. The theory in question intended to explain the origin of mountains and retained some popularity among geologists into the 1870s.[8]

Response to Cosmos

Reception

Cosmos was considered to be both a scientific and literary achievement, immensely popular among nineteenth-century readers.[1] Although the book bore the daunting subtitle of A Sketch of a Physical Description of the Universe, and had an index that ran to more than 1,000 pages, the first volume sold out in two months, the work was translated into all major languages and sold hundreds of thousands of copies.[9] Humboldt's publisher claimed: "The demand is epoch-making. Book parcels destined for London and St. Petersburg were torn out of our hands by agents who wanted their orders filled for the bookstores in Vienna and Hamburg." [9]

Cosmos largely enhanced Humboldt's reputation in his own lifetime, not only in his own country but throughout Europe and America. Its enthusiastic reception in England, where it came out in the Bohn Scientific Library in a translation by Elizabeth Leeves, particularly surprised him. The reviews were gushing in praise of both the author and his work.[4]

However, some felt he had not done justice to the contribution of modern British scientists and many were quick to point out that Humboldt, who had written so exhaustively about the creation of the universe, failed to ever mention God the Creator.[4]

Legacy

Humboldt's Cosmos had a significant impact on scientific progress, as well as various scientists and authors throughout Europe and America.[9] Humboldt's work gave a strong impetus to scientific exploration throughout the nineteenth century, inspiring many, including Charles Darwin, who brought some of Humboldt's earlier writings with him on his voyage as the naturalist aboard the Beagle in the 1830s.[1] Darwin called Humboldt "the greatest scientific traveler who ever lived."[1]

Cosmos influenced several American writers and artists, including Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Frederic Edwin Church.[3] [10] Emerson read Humboldt's work throughout his life, and for him, Cosmos capped Humboldt's role as a scientific revolutionary.[3] Edgar Allan Poe was also an admirer of Humboldt, even dedicating his last major work, Eureka: A Prose Poem, to Humboldt.[3] Humboldt's attempt to unify the sciences was a major inspiration for Poe's work.[3] Walt Whitman was said to have kept a copy of Cosmos on his desk for inspiration as he wrote Leaves of Grass, and Henry David Thoreau's Walden, like Eureka, was a response to Humboldt's ideas.[3] Following the itinerary of Humboldt's expeditions to Colombia and Ecuador, Church found subject matter for some of his most monumental landscape paintings, including The Falls of the Tequendama near Bogota, New Granada.[11]

Although Cosmos and Humboldt's work in general had such a lasting impact on scientific thought, interest in Humboldt's life, work, and ideas over the past two centuries has dwindled in comparison to what it once was.[12] However, starting in the 1990s and continuing to date, an upswing in scholarly interest in Humboldt has occurred.[12] A new edition of Cosmos released in Germany in 2004 received avid reviews, renewing Humboldt's prominence in German society.[12] German media outlets hailed the largely forgotten Humboldt as a new avatar figure for German national renewal and a model cosmopolitan ambassador of German culture and civilization for the twenty-first century.[12]

Humboldt is also credited with laying the foundations of physical geography, meteorology, and especially biogeography. His account in Cosmos of the propagation of seismic waves also became the basis of modern seismology.[4] His most enduring contribution to scientific progress, however, in his conception of the unity of science, nature, and mankind.[1] Cosmos showed nature as a whole, not as unconnected parts.[5]

Editions

- Kosmos: Entwurf einer physischen Weltbeschreibung, editiert und mit einem Nachwort versehen von Ottmar Ette und Oliver Lubrich, Berlin: Die Andere Bibliothek 2014, ISBN 978-3-8477-0014-2.

See also

- Cosmos by Carl Sagan; like Cosmos this 1980 book is wide-ranging, discussing much of the extent of the then-known universe and humankind's place in it

References

- Robert B. Downs, Landmarks in Science: Hippocrates to Carson (Littleton, Colo: Libraries Unlimited, 1982), 189-191.

- Walls, L. D. (2009). "Introducing Humboldt's Cosmos". Minding Nature. August: 3–15.

- Laura Dassow Walls, The Passage to Cosmos: Alexander von Humboldt and the Shaping of America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

- Douglas Botting, Humboldt and the Cosmos (New York: Harper & Row, 1973), 258-262.

- Jeff Lee, Alexander von Humboldt (New York: American Geographical Society, 2001).

- Aaron Sachs, "The Humboldt Current: Nineteenth-Century Exploration and the Roots of American Environmentalism." (New York: Viking, 2006).

- Alexander von Humboldt, Cosmos (George Bell, 1883) 1:24.

- Şengör, Celâl (1982). "Classical theories of orogenesis". In Miyashiro, Akiho; Aki, Keiiti; Şengör, Celâl (eds.). Orogeny. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 4–6. ISBN 0-471-103764.

- Sachs, A. (1995, 03). Humboldt's legacy and the restoration of science. World Watch, 8, 28. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/230005809

- Baron, Frank. (2005). "From Alexander von Humboldt to Frederic Edwin Church: Voyages of Scientific Exploration and Artistic Creativity". HiN. Alexander von Humboldt im Netz. 6.

- Baron, Frank. (2005). "From Alexander von Humboldt to Frederic Edwin Church: Voyages of Scientific Exploration and Artistic Creativity". HiN. Alexander von Humboldt im Netz. 6.

- Kent Mathewson, Humboldt's Twenty-First-Century Currency: Recent Upwellings, Commemorations, and Critical Commentaries" (New York: American Geographical Society, 2006).

External links

- COSMOS: A Sketch of the Physical Description of the Universe, Vol. 1, Translated by E C Otte on Project Gutenberg