Confession album

The confession album, or confession book,[1] was a kind of autograph book popular in late-nineteenth-century Britain. Instead of leaving free room for invented or remembered poetry, it provided a formulaic catechism. The genre died out towards the end of the century, with occasional brief revivals in the twentieth century. The same kind of form is now found in the Dutch vriendenboek ("friends book") and German Freundschaftsbuch ("friendship book"), used by small children; and the questions that the confession album contained live on in the Proust Questionnaire often used for celebrity interviews.

Questions

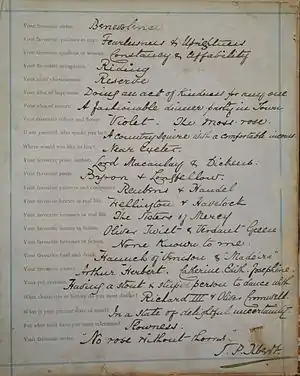

The questions posed in a confession album varied from volume to volume. A typical set of questions, in a book from the 1860s, is given below along with the answers of one respondent (see picture, right). The same set of questions were presented to Queen Victoria's second son, Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in 1873,[2] to Marcel Proust around 1885 and to Claude Debussy in 1889.[3]

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| Your favourite virtue. | Benevolence |

| Your favourite qualities in man. | Fearlessness & Uprightness |

| Your favourite qualities in woman. | Constancy & Affability |

| Your favourite occupation. | Riding |

| Your chief characteristic. | Reserve |

| Your idea of happiness. | Doing an act of kindness for anyone |

| Your idea of misery. | A fashionable dinner party in Town |

| Your favourite colour and flower. | Violet - The Moss-rose |

| If not yourself, who would you be? | A country squire with a comfortable income. |

| Where would you like to live? | Near Exeter. |

| Your favourite prose authors. | Lord Macaulay & Dickens. |

| Your favourite poets. | Byron & Longfellow. |

| Your favourite painters and composers. | Reubens & Handel |

| Your favourite heroes in real life. | Wellington & Havelock |

| Your favourite heroines in real life. | The Sisters of Mercy |

| Your favourite heroes in fiction. | Oliver Twist & Verdant Green |

| Your favourite heroines in fiction. | None known to me. |

| Your favourite food and drink. | Haunch of Venison & "Madeira" |

| Your favourite names | Arthur. Herbert. Catherine. Edith. Josephine. |

| Your pet aversion. | Having a stout and stupid person to dance with. |

| What characters in history do you most dislike? | Richard III & Oliver Cromwell. |

| What is your present state of mind? | In a state of delightful uncertainty. |

| For what fault have you most toleration? | Slowness. |

| Your favourite motto | "No rose without thorns." |

| J. P. Ilbert. |

Among the questions found in other albums, several seem designed to help courtship, sometimes with a reflection of changing relations between the sexes, for instance "What is your opinion of the girl of the period?", " What is your opinion of the man of the period?"[4]

History

Britain and America

The origins of the confession album are unclear. Samantha Matthews notes the similarity to oracle games of the first half of the nineteenth century (she cites examples from 1810 to 1852). These interactive books, which bore titles such as The Young Lady's Oracle: A Fireside Amusement, included questions that resemble those of the confession albums (for instance "Which is your favourite flower?", "Which is your favourite historical character?"), including sexually distinguished questions appropriate to courtship (for instance, "What is the character of your lady love?", "What is the character of him you love?").[5]

Whatever their origins, confession albums were an established form by the 1860s: Henry d'Ideville records using an album in 1861 (see Germany and France below); Karl Marx filled out answers to one in the spring of 1865 (his favourite colour was red); and Friedrich Engels answered another in 1868 (his idea of happiness was Château Margaux 1848).[6] Early albums often had blank pages into which owners would paste the questionnaires; the questions on these could be preprinted or handwritten.[7] One such album with handwritten questions, was that of Karl Marx's daughter Jenny, which contains entries dated from 1865 to 1870. For some of these, she sent the questions to friends, asking them to fill them out and return them. Her comments in a letter of November 1865 suggest that she regarded the genre as a novelty:[8]

I have a whole book filled up in that way and the answers are very amusing when compared with one another. These Confession books have put albums and stamp books quite into the shade. … I should much like to have answers. It is more interesting and amusing than a mere Autograph.

By the end of the decade, the printed and bound confession book had been introduced. The earliest currently known example with a printed publication date is Mental Photographs, an album published in New York in 1869, which contained place for a photograph as well as the set of questions (a combination already found in Jenny Marx's album).[9] The albums seem to have enjoyed their greatest popularity in the following decades, but to have become unfashionable by the early years of the twentieth century. At their height, confession albums were widespread enough that in 1883 Douglas Sladen could rely on readers' familiarity with the form to play on it with a poetical answer.[10] He begins:

My favorite virtue, I confess, is chivalrous devotedness,

My favorite quality in man, the manful genius that can

With iron will and eye sublime, up to the heights of empire climb;

Although in woman, as I think, gentleness is perfection's pink

This ubiquity was accompanied by a certain exasperation. In a novel of 1886, a character asks:[11] "A propos of the confessional, did any of you ever come under the torture of that modern Inquisition, the 'Confession Book?'" Early twentieth century writers look back on the books as a long unfashionable genre. A writer in 1915 records:[12]

So far as I can recollect it was voted a bore at the end of the 'seventies and, except in suburban homes, such as my own, was never referred to except with a yawn or a smile after the early eighties.

The Daily Chronicle in 1906 remarks:[13] "'If not yourself, who would you rather be?' was a favourite question of the confession album of the seventies." A. A. Milne (1882–1956) looked back in 1921 on the album as something from his childhood:[14]

The confession-book, I suppose, has disappeared. It is twenty years since I have seen one. As a boy I told some inquisitive owner what was my favourite food (porridge, I fancy), my favourite hero in real life and in fiction, my favourite virtue in woman, and so forth.

Some album producers saw World War I as an opportunity to revive the confession book. The new albums, unlike their Victorian predecessors, ignored questions appropriate to courtship. They were clearly intended to be filled out by soldiers, a point spelt out in the title of one: My Brave Friend's Confession Book (1915).[15]

Germany and France

According to Henry d'Ideville, he had an "album-questionnaire" in which he collected the responses of friends and acquaintances in 1861, when as a diplomat in Naples he took the answers of Urbano Rattazzi and Mme de Solms, which he reproduces. His account, written in 1872, explains the nature of the album, as though he did not expect readers to be familiar with it:[16]

Here is what the operation consists of: you pose a series of questions to the unfortunate subject of the interrogation and he has to answer them one after the other. – What poet, what painter, what occupation, what pleasure, what sensation, etc. etc. do you prefer? The answers are written down, then the person signs and dates his interrogation and that's the game over.

British confession albums also circulated on the continent (see Questions above), and (perhaps in imitation of them) there were also questionnaire books in other languages. In Germany there were several, notably Erkenne Dich Selbst! ("Know Yourself"), which first appeared in 1878 and survived to around 1900, going through at least 22 impressions, produced by Friedrich Kirchner (1848–1900). The Leipziger Illustrirte Zeitung, which belonged to the same publishers as Kirchner's album, set his questions to celebrities, a forerunner of the modern use as the Proust Questionnaire; facsimiles of these answers were in turn printed in the album. In France, two are known, both containing the word Confidences in the title to represent the English "confessions". Here too the Revue illustrée set confession album questions to the famous, including Zola and Verlaine.[17]

Revivals

Friendship books

In the Netherlands, where autograph books are very popular among young schoolchildren, publishers have recently started bringing out an alternative in the so-called vriendenboek or vriendjesboek ("Friends book"), which much like the confession album come preprinted with a set of questions about the respondents' hobbies, idols and wishes. Some children prefer the new format, which says more about the person answering, but most prefer the traditional autograph book, which leaves more room for their own creativity.[18] The modern German Freundschaftsbuch ("Friendship book") has the same kind of preprinted questions and is typically aimed at the same age group.[19]

Proust Questionnaire

In 1886, Marcel Proust, then a child of fourteen, filled out the answers to an English confession album, which bore the title Confessions. An Album to Record Thoughts, Feelings, &c. (his answers were auctioned in 2003 for $34,000).[20] Interest in Proust led to a later revival of the questions as a kind of formulaic interview for celebrities, first by Léonce Peillard in France in the 1950s, later in French and American television and in the magazine of the German Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, starting in 1980,[21] and in Vanity Fair since 1993, under the name of "The Proust Questionnaire", which disguises its unintellectual British origins.[22] This use too had been anticipated by nineteenth century journals (see Germany and France).

Slam Books

A slam book is a notebook (commonly the spiral-bound type) which is passed among children and teenagers. The keeper of the book starts by posing a question (which may be on any subject) and the book is then passed round for each contributor to fill in their own answer to the question.

Footnotes

- So called by e. g. A. A. Milne, Not that it Matters , London: Methuen (1921), 79; Once a Week , London: Methuen (1922), 180.

- The earliest dated answer in the album pictured is 1868. Prince Alfred's answers are given in A.M. Broadley, Chats on Autographs, London: T. Fisher Unwin (1910), 148-51, with the comment: "It is not often that Royalty honours one of those irritating social tortures entitled 'An Album of Confessions to Record Thoughts and Feelings.'" (online at archive.org).

- Touttavoult (1990), 14-17 (Proust) and 138-9 (Debussy).

- Matthews (2000), 137-8; 141; 145.

- Matthews (2000), 126-30.

- Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Collected Works, London: Lawrence and Wishart, vol. 42 (1987), 567 and 674 (Marx); vol 43 (1988), 541 (Engels). For online transcriptions of the Marx and Engels confessions, and a reproduction of his entry in Jenny's confession book, see External links. Marx filled out answers on two other occasions, including one for his daughter Jenny's confession album, the book from which Engels' confession is taken. Omura et al. (2005) contains a facsimile of this album with some commentary and a (slightly inaccurate) transcription.

- Kohlbecher (2007), 26.

- Omura et al. (2005), 24-5

- R. Saxton (ed.), Mental Photographs. An Album for Confessions of Tastes, Habits and Convictions New York: Leypoldt & Holt (1869). See Kolhbecher (2007), 25-6; 28-9; 32. The questions elicited a satirical response from Mark Twain, "Mental Photographs", published in Mark Twain's Sketches, London: Routledge (1872), 148-9 (online at archive.org).

- D. A. B. Sladen, "A Confession. (Written for a Lady's Character Book)" in Australian Lyrics, Melbourne and Sydney: George Robertson (1883), 39-40. The poem is quoted and discussed in Matthews (2000), 139-40.

- Annie G. Savigny, A heart-song of to-day (disturbed by fire from the 'unruly member'), Toronto: Hunter Rose (1886), Chapter 31 (online at Project Gutenberg).

- C.F. Really & Truly: A Book of Literary Confessions: Designed by a Late-Victorian London: Arthur L. Humphreys (1915), 7, cited in Matthews (2000), 132.

- Quoted in the Oxford English Dictionary s.v. "confession" III.9 and in Matthews (2000), 132; similarly Jerome K. Jerome, Idle Ideas in 1905 London: Hurst & Brackett (1905), 25, speculates about a future revival of the "old confession book".

- A. A. Milne, Not that it Matters, London: Methuen (1921), 79.

- Matthews (2000), 132; 147-51.

- H. d'Ideville, Journal d'un diplomate en Italie, Notes intimes pour servir à l'historie du second empire, Turin 1859-1862, Paris: Hachette, 1872, 101 "Voici en quoi consiste l'opération: On adresse au malheureux interrogé une série de questions auxquelles il doit répondre successivement. – Quel poëte? quelle occupation? quel plaisir? quelle sensation, etc., etc., préférez-vous? Les réponses sont inscrites, puis la personne signe, date son interrogatoire et le tour est joué."

- Kohlbecher (2007), 28-9; 33-4.

- M. Van den Berg, "Zur Erinnerung, Poesiealben aus Flandern", Acta Ethnographica Hungarica 44 (1999), 247-59 (on this point 249).

- For instance Pettersson und Findus - Alle meine Freunde, illustrated by Sven Nordquist, Oetinger (2005), ISBN 978-3-7891-1330-7

- L. Van Gelder, "Arts briefing", New York Times, May 5, 2003.

- Kohlbecher (2007), 25; 29.

- "Proust Questionnaire".

See also

References

- Guido Kohlbecher (2007), "Das Fragebogenalbum des 19. Jahrhunderts", Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Buchforschung in Österreich, 25-35 (online).

- Samantha Matthews (2000), "Psychological Crystal Palace? Late Victorian Confession Albums", Book History 3, 125-54.

- Izumi Omura, Valerij Fomičev, Rolf Hecker and Shun-ichi Kubo, eds. (2005), Familie Marx privat, Die Foto- und Fragebogen-Alben von Marx' Töchtern Laura und Jenny Berlin: Akademie Verlag, ISBN 3-05-004118-8

- Fabrice Touttavoult (1988), Confessions, Paris: Éditions Belin; German translation by J. Kunze (1990), Bekentnisse, Stuttgart, Patricia Schwarz, ISBN 3-925911-22-7. A collection of confessions by famous nineteenth century figures (with discussion): Cézanne, Debussy, Engels, Mallarmé, Marx, Proust. As Kohlbecher (2007) notes, the author's name ("avows everything") seems to be a pseudonym.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Confessions album. |

- Confession album entries for Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels at marxists.org

- Confession album answers by Marcel Proust