Compulsion loop

A compulsion loop or core loop is a habitual chain of activities that will be repeated by the user to cause them to continue the activity. Typically, this loop is designed to create a neurochemical reward in the user such as the release of dopamine.

Compulsion loops are deliberately used in video game design as an extrinsic motivation for players, but may also result from other activities that create such loops, intentionally or not, such as gambling addiction and Internet addiction disorder.

Basis

The understanding of the motivations of compulsion loops came out of experiments performed on laboratory animals in operant conditioning chamber or a "Skinner box", where the animals are given both positive and negative stimuli for performing certain actions, such as providing food by pressing a lever. Besides demonstrating that animals would prefer positive rewards and thus learned to trigger the correct lever, B. F. Skinner found that the effects of random rewards and variable time between awards also became a factor towards how quickly the animals learned the rules of the positive reinforcement system.[1] Ongoing research has shown that dopamine, synthesized in the animal brain, is a key neurotransmitter involved in this process; disabling the ability for receptors to react to dopamine in animal studies can impact how rapidly the animals can be conditioned.[2]

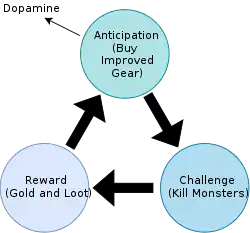

Applying these principles to gaming, a compulsion loop creates a three-part cycle: the anticipation of receiving some reward, the activity that must be completed to receive that reward, and the act of finally obtaining the reward. From a neuroscience aspect, it is believed that the anticipation phase is where dopamine is created by the human brain, while it is released upon obtaining the reward.[3][4][5] Dopamine creates feelings of pleasure in the brain and drives motivation, and while the neurotransmitter itself is not addictive, can lead to addictive behavior as the user desires to experience the further dopamine release.[6][7]

In game design

A core or compulsion loop is any repetitive gameplay cycle that is designed to keep the player engaged with the game. Players perform an action, are rewarded, another possibility opens and the cycle repeats.[8] A compulsion loop may be distinguished further from a core loop; while many games have a core loop of activities that a player may repeat over and over again, such as combat within a role-playing game, a compulsion loop is particularly designed to guide the player into anticipation for the potential reward from specific activities.[1] The compulsion loop can be strengthened by adding a variable ratio schedule, where each response has a chance of producing a reward. Another strategy is an avoidance schedule, where the players work to postpone a negative consequence.[4] Without a lack of meaningful reward, the player may eventually no longer engage with the game, causing extinction of the player population for a game. Particularly for freemium titles, where players can opt to spend real-world money for in-game boosts, extinction is undesirable so the game is designed around a near-perpetual compulsion loop alongside frequent addition of new content.[4]

Compulsion loops in video games can be established through several means. One common approach is to show the player a "baseline" for how powerful the player-character could become, such as starting the game in an advanced power state and shortly stripping the character of those advancements and having the player rebuild the character to that state, or to show them a powerful non-player character that their starting character could eventually build towards. Another approach is through the difficulty curve of the game, making enemies stronger as the player-characters advances deeper into the game, and requiring the player to spent time to improve the character whether through new gear, abilities, or the player's own performance to progress. In multiplayer games, players may also be simply driven by envy towards other players that have more powerful characters.[9] Some loops can rely on the concept of withdrawal, in that the player may get to a state in the game they are content with, but by some means, the game shows the player a potential of where they could be by improving, and anticipating the player to feel like they are lacking something and will return to engage in the game.[9]

A well-known example of a compulsion loop in video games is the Monster Hunter series by Capcom. Players take the role of a monster hunter, using a variety of weapons and armor to slay or trap the creatures. By doing so, they gain monster parts and other loot that can be used to craft new weapons and equipment that is typically stronger than their previous gear. The loop presents itself that players use their current equipment to hunt monsters with a given difficulty level that provide parts that can be used to craft improved equipment. This then lets them face more difficult monsters that provide parts for even better gear. This is aided by the random nature of the drops (a variable ratio), sometimes requiring players to repeat quests several times to get the right parts.[10][11]

Another type of compulsion loop are offered through many games in the form of a loot box or similar term, depending on the game. Loot boxes are earned progressively by continuing to play the game; this may be as a reward for winning a match, purchasable through in-game currency that one earns in game, or through microtransactions with real-world funds. Loot boxes contain a fixed number of randomly chosen in-game items, with at least one guaranteed to be of a higher rarity than the others. For many games, these items are simply customization options for the player's avatar that has no direct impact on gameplay, but they may also include gameplay-related items, or additional in-game currency. Loot boxes work under the psychology principle of variable rate reinforcement, which causes dopamine production at higher rates due to the unpredictable nature of the reward in contrast to fixed rewards.[12] In many games, opening a loot box is accompanied by visuals and audios to heighten the excitement and further this response. Overall, a loot box system can encourage the player to continue to play the game, and potentially spend real-world funds to gain loot boxes immediately. Controversy arose in 2018 around loot boxes with several experts, governments, and concerns citizens fearing that loot boxes could lead to gambling, particularly in youth, and some governments took step to ban loot box practices that involved real-world funds.[12]

Compulsion loops can be used as a replacement for game content, especially in grinding and freemium game experience models. The opposite of rewarding predictable, tedious and repetitive tasks are reward action contingency based systems, where players overcome game challenges with clear signals of progress.[13]

Psychological effects

Encouraging players to return to the game world can lead to video game addiction.[14] Internet addiction disorder can also result from a compulsion loop created by users in checking email, websites, and social media to see the results of their actions.[15][5] A further concern related to compulsion loops in video games is a potential for violent video games to lead to violent behavior. While the American Psychological Association (APA) had asserted in 2019 that there is no direct connection between violent video games and real-world violent behavior,[16] some still fear that compulsion loops in these types of games can help to reinforce violence tendencies.[17]

References

- Kim, Joseph (March 23, 2014). "The Compulsion Loop Explained". Gamasutra. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- Barrus, Michael M.; Winstanley, Catharine A. (January 20, 2016). "Dopamine D3 Receptors Modulate the Ability of Win-Paired Cues to Increase Risky Choice in a Rat Gambling Task" (PDF). The Journal of Neuroscience. 36 (3): 785–794. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2225-15.2016. PMID 26791209. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- Samson, Sebastien (November 13, 2017). "Compulsion Loops & Dopamine in Games and Gamification". Gamasutra. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- Hopson, John (April 27, 2001). "Behavioral Game Design". Gamasutra. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- Davidow, Bill (July 18, 2012). "Exploiting the Neuroscience of Internet Addiction". The Atlantic. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- Baliki MN, Mansour A, Baria AT, Huang L, Berger SE, Fields HL, Apkarian AV (October 2013). "Parceling human accumbens into putative core and shell dissociates encoding of values for reward and pain". The Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (41): 16383–93. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1731-13.2013. PMC 3792469. PMID 24107968.

- Wang, Qianjin; Ren, Honghong; Long, Jiang; Liu, Yueheng; Liu, Tieqiao (July 18, 2018). "Research progress and debates on gaming disorder". General Psychiatry. 32 (3): e100071. doi:10.1136/gpsych-2019-100071. PMC 6678059. PMID 31423477.

- Keith Stuart: My favourite waste of time: why Candy Crush and Angry Birds are so compulsive, The Guardian, 21 May 2014

- Mandryka, Alexandre (August 10, 2016). "Compulsion loop is withdrawal-driven". Gamasutra. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- Busby, James (December 2, 2016). "The First Monster Hunters". Kotaku UK. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- Stranton, Rich (July 15, 2016). "Monster Hunter Generations review – fantastic beast hunt hits new heights". The Guardian. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- Wiltshire, Alex (September 28, 2017). "Behind the addictive psychology and seductive art of loot boxes". PC Gamer. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- Brock, Dubbels (2016-11-23). Transforming Gaming and Computer Simulation Technologies across Industries. IGI Global. ISBN 9781522518181.

- Mez Breeze: A quiet killer: Why video games are so addictive, TNW, Jan 12, 2013

- Schwartz, Tony (November 29, 2015). "Addicted to Distraction". The New York Times. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- Draper, Kevin (August 5, 2019). "Video Games Aren't Why Shootings Happen. Politicians Still Blame Them". The New York Times. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Parkin, Simon (August 8, 2019). "No, Video Games Don't Cause Mass Shootings. But The Conversation Shouldn't End There". Time. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

Amy Edwards - 25th June 2020 The Rest Of Us Just Live Here by Patrick Ness