Commercial graffiti

Commercial graffiti (also known as aerosol advertising or graffiti for hire) is the commercial practice of graffiti artists being paid for their work. In New York City in particular, commercial graffiti is big business and since the 1980s has manifested itself in many of the major cities of Europe such as London, Paris and Berlin. Increasingly it has been used to promote video games and even feature prominently within them, reflecting a real life struggle between street artists and the law. Commercial graffiti has created significant controversy between those who view it as an effective medium of advertising amongst specific target audiences and those who believe that legal graffiti and advertising using it encourages illegal graffiti and crime.

History

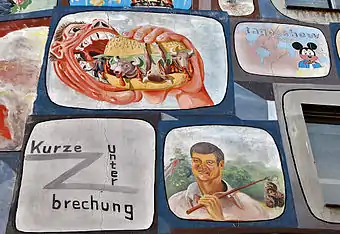

Graffiti as a commercial activity dates back to Ancient Greece,[1][2] when pottery makers employed artists to decorate their items with motifs and intricate designs.[3] The modern era, the phenomenon has been strongly associated with New York City since the late 1960s and the hip hop culture that emerged in the 1980s, according to a 1993 New York Times article that focused on the issue.[4] The term "commercial graffiti" was used in an article by Time as early as 1968 and used to describe activity in Chicago as early as 1970.[5][6] In 1981, Times Square was referenced as featuring "commercial graffiti" through "Japanization", and more recently further "Japanization" of children's culture is cited to be taking place through forms of graffiti in video games and in the increasing popularity of Japanese innovations such as anime.[7][8] Since the early 1980s, commercial graffiti has evidenced itself in Los Angeles[9] and other major American cities[10] and across Europe, particularly Paris, and London and Berlin and features on the walls of numerous galleries across Europe.[11]

With the increasing popularity and legitimization of graffiti, it has increasingly undergone commercialization. In 2001, computer giant IBM launched an advertising campaign in Chicago and San Francisco which involved people spray painting on sidewalks a peace symbol, a heart, and a penguin (Linux mascot), to represent "Peace, Love, and Linux." However, due to illegalities some of the street artists were arrested and charged with vandalism, and IBM was fined more than US$120,000 for punitive and clean-up costs.[12][13]

Controversy

The practice of commercial artistry is controversial,[14] because many commercial establishments feel that professional graffiti art is a valuable form of advertising, while other businesses, law enforcement and others disagree. Legal and commercial graffiti is increasing and has created significant debate amongst graffiti writers and those associated with hip-hop culture.[15] The primary concern by those who oppose graffiti is that the tolerance of professional graffiti in one space leads to more illegal graffiti in other spaces. In some areas such as sports, over advertising in sports venues and even player uniforms in soccer has sometimes been viewed negatively.[16]

Commercial graffiti, seen as a frontier between the street world and the art world,[17] is argued in some cases to promote a more responsible lifestyle for the graffiti artist through formal employment, which may range from actual graffiti advertising on buildings, to making prints and logos for clothing and gallery showcasing.[18] Nancy MacDonland in her book The graffiti subculture: youth, masculinity, and identity in London and New York argues that commercial graffiti artistry "moves writers out of the boundaries of the subculture", because artists "no longer paint for their peers and themselves, they have a new audience".[18]

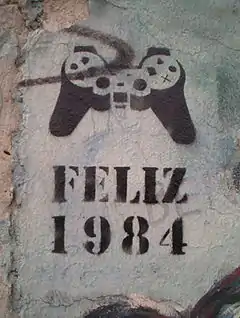

Even in major cities such as New York City and Chicago, commercial graffiti has created some very mixed reactions. For instance in Chicago, despite a significant following in graffiti artistry, in the mid 1980s a commercial which featured a kid spraying "The end is near" caused considerable outrage by Chicago citizens who protested to the Ford Motor Company to take the commercial off air as they believed it encouraged children to freely graffiti property as they desire.[19] Similarly, in 2005, Peter Vallone Jr., a City Council member in New York and several other councilors protested against Sony's decision to use graffiti commercially in their PlayStation Portable advertising in New York, Chicago, Atlanta, Philadelphia, Los Angeles and Miami as they believed it would have a negative influence on children and encourage them to deface property.[20]

Commercial success

In New York City, legal graffiti and employment has become big business, appearing with owners' permission on everything from walls to railroad boxcars.[21] According to Cooper and Sciorra, many young graffiti artists are keen to use their talents and aspire to achieve entrepreneurial success.[21] Local businesses employing well-known graffiti artists are also said to enhance their credibility and business-customer relationship as well as reducing crime by employment.[21] One prominent group in New York City is the "King of Murals" which run a commercial graffiti business and have been employed to promote global brands such as Coca-Cola and M&M's in advertising campaigns and even hired by schools, hospitals and other healthcare groups to create artwork.[21] Bronx-based TATS CRU has made a name for themselves doing legal advertising campaigns for companies like Coca-Cola, McDonald's, Toyota, and MTV. Smirnoff and even Microsoft have hired artists to use reverse graffiti (the use of high pressure hoses to clean dirty surfaces to leave a clean image in the surrounding dirt) to increase awareness of their product.[22] In 2011, Klughaus Gallery started Graffiti USA, a company offering interior graffiti murals for companies. Their work includes murals at the corporate offices of Linked In, Facebook, MasterCard, and ABC News, which featured a Graffiti USA commissioned mural on October 8, 2014 episode of Nightline.[23]

In Boston, Massachusetts, a company named Alt Terrain specializes in hiring graffiti writers to paint legal murals as part of public performances which are hyped as "brand events" and may cost up to $12,500 for live performances.[21] In Pittsfield, Massachusetts for example, after the death of Michael Jackson, Solomon "Disco" Stewart and a team of four artists named "The Berkshire Graffiti Network" for instance were paid to paint a "Michael Jackson Tribute" mural on the wall of a Pittsfield market on North Street.

In the United Kingdom, Covent Garden's Boxfresh used stencil images of a Zapatista revolutionary in the hopes of cross referencing would promote their store. Even the Israeli West Bank barrier has acted as a canvas for professional graffiti for hire teams. One Palestinian pacifist group will spray paint any message for 30 Euros, providing that it is not racist or violently motivated.[24] The Art Crimes website is the first to be established in the field of commercial graffiti and hires some sixty artists to produce artwork.[21]

In video games

Graffiti has become an important part of video game culture, often reflecting the oppression facing graffiti artists in public and battle for it to be seen by the establishment as a legitimate and indeed a legal art form. The Jet Set Radio series (2000–2003) tells the story of a group of teens fighting the oppression of a totalitarian police force that attempts to limit the graffiti artists' freedom of speech [8] and others such as Rakugaki Ōkoku series (2003–2005) for Sony's PlayStation 2 [25] revolves around an anonymous hero and his magically imbued-with-life graffiti creations as they struggle against an evil king who only allows art to be produced which can benefit him. Similarly Marc Eckō's Getting Up: Contents Under Pressure (2006), features a story line involving training in graffiti artistry and fighting against a corrupt city and its oppression of free speech, as in the Jet Set Radio series.[26] Numerous other non-graffiti-centric video games allow the player to produce graffiti, such as the Half-Life series, the Tony Hawk's series, The Urbz: Sims in the City, Rolling and Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas.

In apparel

Graffiti has become a common stepping stone for many members of both the art and design community in North America and abroad. Within the United States, graffiti artists such as Mike Giant, Persue, Rime, Noah and countless others have made careers in skateboard, apparel and shoe design for companies such as DC Shoes, Adidas, Rebel8 Osiris or Circa[27] Meanwhile, there are many others such as DZINE, Daze, Blade, The Mac etc. which have developed into gallery artists and at times do not even use their initial medium (spray paint) to produce artwork.[27]

Keith Haring, a well-known graffiti artist, contributed to bringing graffiti to the commercial mainstream. In the 1980s, Haring opened his first Pop Shop: a store that offered everyone access to his works—which until then could only be found spray-painted on city walls. Pop Shop offered commodities like bags and T-shirts. Haring explained that, "The Pop Shop makes my work accessible. It's about participation on a big level, the point was that we didn't want to produce things that would cheapen the art. In other words, this was still art as statement". Marc Ecko, an urban clothing designer, has been an advocate of graffiti as an art form during this period, stating that "Graffiti is without question the most powerful art movement in recent history and has been a driving inspiration throughout my career."[28]

But perhaps the greatest example of graffiti artists infiltrating mainstream pop culture is by the French crew, 123Klan. 123Klan founded as a graffiti crew in 1989 by Scien and Klor, have gradually turned their hands to illustration and design while still maintaining their graffiti practice and style.[29] In doing so they have designed and produced, logos and illustrations, shoes, and fashion for numerous global firms.

Tourism

Most of the major cities across the world have graffiti and street art tours, often run by local graffiti artists who want to bring their talent to the public on a more socially accepted level.[30]

Originally started with walking or biking tours around the cities, street art tours have expanded to include graffiti workshops, using graffiti art tools, stencils and spray cans.

Tours exist in New York, London, Berlin, Hamburg, Reykjavik, Barcelona, Montreal and Paris.[31]

Marketing

Commercial graffiti is used as a type of marketing known as guerrilla marketing where one company has limited funds for advertising its product may it be goods or services. Generally done by smaller companies at the beginning due to small budgets but adopted by big brands (e.g. Coca-Cola[32]). This type of marketing has a way of going viral as it is done in a public place with limited resources but with new technology such as smart phones which can upload pictures and videos instantly to social media, so if there is legal permission by the government for graffiti people would do it during peak hours in communities for maximum exposure[33]( Navrátilová, L. Milichovský, F(2015)).

References

- Kipfer, Barbara Ann (2007). Dictionary of artifacts. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-4051-1887-3. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Morgan, Catherine; Tsetskhladze, Gocha R. (September 2004). Attic fine pottery of the archaic to Hellenistic periods in Phanagoria. BRILL. p. 150. ISBN 978-90-04-13888-9. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Morris, Ian (1994). Classical Greece: ancient histories and modern archaeologies. Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-521-45678-4. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Marriott, Michel (October 3, 1993). "Too Legit to Quit". The New York Times. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- Hoffmann, Frank W.; Bailey, William G. (23 July 1990). Arts & entertainment fads. Harrington Park Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-918393-72-2. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Fellowship of Religious Humanists (1970). Religious humanism. Fellowship of Religious Humanists. p. 120. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- New York Media, LLC (17 August 1981). New York Magazine. New York Media, LLC. p. 17. ISSN 0028-7369. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- West, Mark I. (2009). The Japanification of children's popular culture: from godzilla to miyazaki. Scarecrow Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-8108-5121-4. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Price, Vincent Barrett (18 April 2003). Albuquerque: a city at the end of the world. UNM Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8263-3097-0. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Brodkin, Sylvia Z.; Pearson, Elizabeth J. (1975). Native voices: a collection of modern essays. Globe Book Co. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-87065-176-2. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- New Europe College (1 January 2003). New Europe College regional program yearbook. New Europe College. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Niccolai, James (April 19, 2001). "IBM's graffiti ads run afoul of city officials". CNN. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- "Sony Draws Ire With PSP Graffiti". Wired. December 5, 2005. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Eskilson, Stephen (2007). Graphic design: a new history. Laurence King. ISBN 978-1-85669-512-1. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Iveson, Kurt (2007). Publics and the city. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-4051-2730-1. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Murray, Bill; Murray, William J. (1 January 1998). The world's game: a history of soccer. University of Illinois Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-252-06718-1. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Pereira, Sandrine (25 May 2005). Graffiti. Silverback Books. p. 104. ISBN 978-2-7528-0181-4. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Macdonald, Nancy (4 September 2001). The graffiti subculture: youth, masculinity, and identity in London and New York. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-333-78190-6. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Johnson Publishing Company (November 1984). Ebony Jr. Johnson Publishing Company. p. 31. ISSN 0022-2984. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- "Sony asked to clean up NYC graffiti ads". Ars Technica. January 16, 2006. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Snyder, Gregory J. (January 2009). Graffiti lives: beyond the tag in New York's urban underground. NYU Press. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-0-8147-4045-3. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Forsyth, Patrick (2009). Marketing: A Guide to the Fundamentals. Bloomberg Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-1-57660-329-1. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- "abcnews.go.com/Nightline/video/watch-artists-created-nightline-graffiti-mural-26063838". ABC News. 9 Oct 2014.

- McGirk, Tim. Graffiti for Hire in the West Bank. Time. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- "Graffiti Kingdom: Playstation 2 Video Game Review". Kidzworld. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Stang, Bendik (1 November 2006). The book of games. Book of Games. p. 96. ISBN 978-82-997378-0-7. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Ganz, Nicolas. "Graffiti World". New York. Abrams. 2004

- "Marc Ecko Hosts "Getting Up" Block Party For NYC Graffiti, But Mayor Is A Hater". SOHH.com. August 17, 2005. Archived from the original on October 4, 2006. Retrieved October 11, 2006.

- Computer arts. Future. 1 January 2004. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- "Incredible Street Art Tours". Telegraph. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- "Conde Nast Traveler". Conde Nast Traveler. 7 November 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- "Coca-Cola Small World Machines -- Bringing India & Pakistan Together". Archived from the original on 2013-05-20.

- Ludmila, František, Navrátilová, Milichovský. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Strategic Innovative Marketing (IC-SIM 2014), Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 12 February 2015 175:268-274. Elsevier Ltd. pp. 268–274.