Colpidium colpoda

Colpidium colpoda are free-living ciliates commonly found in many freshwater environments including streams, rivers, lakes and ponds across the world.[1] Colpidium colpoda is also frequently found inhabiting wastewater treatment plants. This species is used as an indicator of water quality and waste treatment plant performance.

| Colpidium colpoda | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Colpidium colpoda | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Tetrahymenidae |

| Genus: | Colpidium |

| Binomial name | |

| Colpidium colpoda (Losana, 1829) Ganner & Foissner, 1989 | |

History and physical characteristics

The first record of Colpidium colpoda was in 1829 by Mathaeo Losana, who placed it in the genus Paramaecia.[2] It was more thoroughly described by Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg in his two volume publication Die Infusionsthierchen als vollkommene Organismen (which roughly translates to “The Infusoria as Perfect Organisms”) in 1838. The species was described in detail by Ganner and Foissner in 1989.[1]

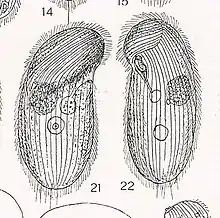

C. colpoda is considered an intermediate sized ciliate,[3] typically between 50 and 150 μm long. The cell is roughly oval or kidney-shaped in profile, with a distinct concavity on the anterior of the oral side. Cilia are arranged in 50-63 longitudinal rows. At the center of the cell is a large, ovoid macronucleus and a small spherical micronucleus. A single contractile vacuole is located slightly posterior to the middle of the body, near the right side.[4]

Like many ciliates, it is a heterotrophic bacterivore that ingests bacteria through an oral groove. C. colpoda reproduces asexually every 4–6 hours,[5] with variation in division rates arising from environmental conditions and the identity of the available bacterial food source.[6]

Phylogeny

In general, it is believed that ciliates form a monophyletic group that diverged from other eukaryotes early in evolutionary history, following the evolution of heterokaryotic genetic systems but prior to the evolution of multicellularity and some organelles such as endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi complex.[7] Colpidium falls within the ciliate taxonomic order Hymenostomatida, which also includes the well-studied Tetrahymena and Glaucoma genera. Previous work suggests that Colpidium seems to be more closely related to Glaucoma than to Tetrahymena.[8] However, more recent analyses have found the opposite – that Colpidium is, in fact, more closely related to Tetrahymena than to Glaucoma.[9]

Genetics

Although a complete genome is not available for Colpidium colpoda, partial sequences have been published for the small subunit 18S rRNA gene and the cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene[10] and complete sequences for the telomerase RNA gene[11] and the 5.8S rRNA gene.[12] Within the same taxonomic family as C. colpoda is the microbial model organism Tetrahymena thermophila. There is a large body of scientific literature on the T. thermophila genome as a representative of the Alveolates, a major evolutionary branch of eukaryotes that includes all ciliates, dinoflagellates and apicomplexans.[13] Like many ciliates, T. thermophila has a surprisingly complex genome that consists of a germline micronucleus and a somatic macronucleus that function and replicate independently of one another. In 2006, the full genome of the T. thermophila macronucleus was sequenced[14]

Ecology

Because Colpidium colpoda feeds on bacteria, this species is typically found in heavily polluted freshwater habitats. For this reason, presence of C. colpoda is often seen as an indicator of poor water quality.[15] C. colpoda and its congeners are also commonly used in laboratory microcosm experiments.[16] Colpidium colpoda can be used to accelerate the rate of degradation of crude oil during bioremediation,[17] although the exact mechanism behind this relationship is unclear. Speculation points toward secretion of mucus that acts as an emulsifier, mechanical action of cilia contributing to emulsification and reduction of competition between bacteria that contribute to hydrocarbon degradation and those that do not through grazing, amongst other possibilities.

References

- Ganner, B.; Foissner, W. (1989). "Taxonomy and ecology of some ciliates (Protozo, Ciliophora) of the saprobic system. III. Revision of the genera Colpidium and Dexiostoma, and establishment of a new genus, Paracolpidium nov. gen". Hydrobiologia. 182 (3): 181–218. doi:10.1007/BF00007515.

- Losana, Mathaeo (1829). "De Animalculis Microscopicis seu Infusoriis". Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Fenchel, T. (1980). "Suspension feeding in ciliated protozoa: functional response and particle size selection". Microbial Ecology. 6 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/BF02020370. PMID 24226830.

- Foissner, Wilhelm; Berger, Helmut; Kohmann, F. (1994). Taxonomische und Ökologische Revision der Ciliaten des Saprobiensystems – Band III: Hymenostomata, Prostomatida, Nassulida. Bayerisches Landesamt für Wasserwirtschaft. p. 43.

- Cutler, D.W.; Crump, L.M. (1923). "The rate of reproduction in artificial culture of Colpidium colpoda". Biochemical Journal. 17 (2): 174–86. doi:10.1042/bj0170174. PMC 1259336. PMID 16743173.

- Burbanck, W.D. (1942). "Physiology of the ciliate Colpidium colpoda. I. The effect of various bacteria as food on the division rate of Colpidium colpoda". Physiological Zoology. 15 (3): 342–362. doi:10.1086/physzool.15.3.30151646. JSTOR 30151646.

- Lukashenko, N.P. (2009). "Molecular evolution of ciliates (Ciliophora) and some related groups of protozoans". Russian Journal of Genetics. 45 (8): 885–898. doi:10.1134/S1022795409080018.

- Chantangsi, C.; Lynn, D.H. (2008). "Phylogenetic relationships within the genus Tetrahymena inferred from the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 and the small subunit ribosomal RNA genes". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 49 (9): 979–987. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.09.017. PMID 18929672.

- Strüder-Kypke, M.C.; Lynn, D.H. (2010). "Comparative analysis of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene in ciliates (Alveolata, Ciliophora) and evaluation of its suitability as a biodiversity marker". Systematics and Biodiversity. 8 (1): 131–148. doi:10.1080/14772000903507744.

- Chantangsi, C.; Lynn, D.H.; Brandl, M.T.; Cole, J.C.; Hetrick, N.; Ikonomi, P. (2007). "Barcoding ciliates: a comprehensive study of 75 isolates of the genus Tetrahymena". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 57 (10): 2412–2423. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.64865-0. PMID 17911319. Archived from the original on 2015-01-18.

- Amanda, J.Y.; Romero, D.P. (2002). "Phylogenetic relationships amongst tetrahymenine ciliates inferred by a comparison of telomerase RNAs". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 52 (6): 2297–2302. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02183-0. Archived from the original on 2015-01-18.

- Van Bell, C.T. (1985). "5S and 5.8 S ribosomal RNA evolution in the suborder Tetrahymenina (Ciliophora: Hymenostomatida)". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 22 (3): 231–236. Bibcode:1985JMolE..22..231V. doi:10.1007/BF02099752. PMID 3935804.

- Stover, N.A.; Krieger, C.J.; Binkley, G.; Dong, Q.; Fisk, D.G.; Nash, R.; Sethuraman, A.; Weng, S.; Cherry, J.M. (2006). "Tetrahymena Genome Database (TGD): a new genomic resource for Tetrahymena thermophila research". Nucleic Acids Research. 34 (1): D500–3. doi:10.1093/nar/gkj054. PMC 1347417. PMID 16381920.

- Eisen, J.A.; et al. (2006). "Macronuclear genome sequence of the ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila, a model eukaryote". PLoS Biology. 4 (9): e286. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040286. PMC 1557398. PMID 16933976.

- Al-Shahwani, S.M.; Horan, N.J. (1991). "The use of protozoa to indicate changes in the performance of activated sludge plants". Water Research. 25 (6): 633–638. doi:10.1016/0043-1354(91)90038-R.

- Lawler, S.P.; Morin, P.J. (1993). "Food web architecture and population dynamics in laboratory microcosms of protists". American Naturalist. 141 (5): 675–686. doi:10.1086/285499. JSTOR 2462826. PMID 19426005.

- Rogerson, A.; Berger, J. (1983). "Enhancement of the microbial degradation of crude oil by the ciliate Colpidium colpoda". The Journal of General and Applied Microbiology. 29 (1): 41–50. doi:10.2323/jgam.29.41.

Further reading

- Foissner, W.; Berger, H. (1996). "A user‐friendly guide to the ciliates (Protozoa, Ciliophora) commonly used by hydrobiologists as bioindicators in rivers, lakes, and waste waters, with notes on their ecology". Freshwater Biology. 35 (2): 375–482.

- Foissner, W (2006). "Biogeography and dispersal of micro-organisms: a review emphasizing protists". Acta Protozoologica. 45 (2): 111–136.