Colored Conventions Movement

The Colored Conventions Movement, or Negro Convention Movement, was a series of national, regional, and state conventions held irregularly during the decades preceding and following the American Civil War. The delegates who attended these conventions consisted of both free and fugitive African Americans including religious leaders, businessmen, politicians, writers, publishers, and abolitionists. The conventions provided "an organizational structure through which black men could maintain a distinct black leadership and pursue black abolitionist goals."[1] The minutes from these conventions show that Antebellum African-Americans sought justice beyond the emancipation of their enslaved countrymen: they also organized to discuss issues concerning labor, healthcare, temperance and educational equality.[2] Although the conventions largely subsided following the Civil War, the Colored Conventions of antebellum America are seen as the precursors to larger African American organizations, including the Colored National Labor Union, the Niagara Movement, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.[3]

History

In the early 19th century, national and local conventions involving a variety of political and social issues were pursued by increasing numbers of Americans. In 1830 and 1831, political parties held their first national nominating conventions.[4] Historian Howard H. Bell notes that the convention movement grew out of a trend toward greater self-expression among African Americans and was largely fostered by the appearance of newspapers such as Freedom's Journal, and was first suggested by Hezekiah Grice.[5] The first documented convention was held at Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church in Philadelphia in September 1830.[6] Delegates to this convention discussed the prospect of emigrating to Canada to find refuge from the harsh fugitive slave laws and legal discrimination under which they lived.[7] The first convention elected as president Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), the first independent black denomination in the United States. The idea of buying land in Canada quickly gave way to addressing problems they faced at home, such as education and labor rights.

Philadelphia was the hub of the Colored Conventions movement for several years before nearby cities such as New York City, Albany, and Pittsburgh also started hosting conventions. By the 1850s, the conventions were extremely popular and multiple national, state, and local conventions were held every year. Although the majority of these conventions were held in northern, particularly New England states, conventions are documented as taking place in Kansas, Louisiana, and California. The conventions attracted the most prominent African-American leaders from across the country, including Frederick Douglass, Charles Bennett Ray, Lewis Hayden, Charles Lenox Remond, Mary Ann Shadd, and William Still.

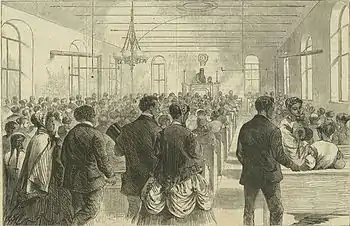

Following the Civil War, colored conventions began to appear in the Southern states as well, with one author noting that "we can not deny that the various conventions of the colored people in the late insurrectionary States compare favorably with those of their white brethren...their reasolutions are of an elevated humanity and common sense to which those of the other Conventions make no pretension."[8]

The post-war conventions culminated with the 1869 National Convention of Colored Men in Washington, D.C. The convention delegates wrote a letter congratulating General Ulysses S. Grant for being elected President of the United States, to which Grant responded, "I thank the Convention, of which you are the representative, for the confidence they have expressed, and I hope sincerely that the colored people of the Nation may receive every protection which the laws give to them. They shall have my efforts to secure such protection."[9]

List of conventions

- 1830 convention at Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church in Philadelphia

- 1831 First Annual Convention of the People of Color, Philiadelphia (proceedings published)[10]

- 1833 Third Annual Convention for the Improvement of the Free People of Color in these United States, Philadelphia

- 1834 Fourth Annual Convention for the Improvement of the Free People of Color in the United States, New York

- 1835 Fifth Annual Convention for the Improvement of the Free People of Color in the United States, Philadelphia

- 1835 Convention which formed the Maine Union in behalf of the Colored Race

- 1840 New York State Convention of Colored Citizens, Albany, New York

- 1841 State Convention of the Colored Freemen of Pennsylvania, held in Pittsburgh, on the 23rd, 24th and 25th of August, 1841, for the purpose of considering their condition, and the means of its improvement

- 1843 National Convention of Colored Citizens in Buffalo, New York

- 1847 National Convention of Colored People and Their Friends in Troy, New York

- 1848 National Convention of Colored Freemen in Newark, New Jersey

- 1849 State Convention of the Colored Citizens of Ohio

- 1851 Address to the constitutional convention of Ohio, from the State Convention of Colored Men

- Colored National Convention of 1855 at Franklin Hall (Philadelphia)

- 1855 First State Convention of the Colored Citizens of California

- Convention of Colored Men, Chatham, Canada West, May 8–10, 1858, organized by John Brown.[11]

- 1864 Proceedings of the National Convention of Colored Men, Syracuse, New York

- 1865 State Equal Rights' Convention, of the Colored People of Pennsylvania, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

- 1865 South Carolina State Convention of Colored People in Charleston, South Carolina

- 1865 First Annual Meeting of the National Equal Rights League , Cleveland, Ohio. The "John Brown Song" was sung at the meeting (p. 11).

- 1867 Illinois State Convention of Colored Men

- 1869 National Convention of Colored Men of America, Washington, D.C.

- 1870 Colored Labor Convention, Saratoga Springs, New York

- 1871 State convention of the colored citizens of Tennessee

- 1873 National Civil Rights Convention in Washington D.C.

Legacy

As national, state, and local colored conventions began to decline, other national organizations popped up. In response to a denial of African American admittance to the National Labor Union, community leaders and others formed the Colored National Labor Union (CNLU) in December 1869.[12] Former Colored Convention delegates Isaac Myers and Frederick Douglass were instrumental in organizing the CNLU.[13]

The last known colored convention took place in Indianapolis in 1887.[14] The convention movement slowed by the end of the century, and it re-emerged in the early twentieth century as the NAACP, founded in 1909. In the interim, T. Thomas Fortune's National Afro-American League was formed in 1890 and held national and state-level meetings throughout the 1890s. From 1896 to 1914, W. E. B. Du Bois held an annual conference at Atlanta University of national importance. In 1898, bishop Alexander Walters founded the National Afro-American Council, which met annually until 1907 and with Fortune and Booker T. Washington playing prominent roles. In 1905, Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter met near Niagara Falls, Canada, founding the Niagara Movement. Du Bois' continued activism and relationships forged at these meetings led to the foundation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People by Moorfield Storey, Mary White Ovington and Du Bois.

See also

- Richard Allen

- Colored National Labor Union

- Frederick Douglass

- George T. Downing

- Henry Highland Garnet

- First National Conference of the Colored Women of America

- Henry Moxley

- Mary Ann Shadd

- The Atlanta Conference of Negro Problems and the Hampton Negro Conference, both of which began in the 1890s and spilled over into the twentieth century

References

- Yee, Shirley J. (1992). Black Women Abolitionists, A Study in Activism, 1828–1860. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press. pp. 143. ISBN 0870497367.

- "Colored Conventions Project". Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- Bell, Howard. Minutes and Proceedings of the Negro Convention Movement. Argo. Archived from the original on April 16, 2014. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- Webber, Christopher L. (2011). American to the Backbone. New York: Pegasus Books. pp. 63. ISBN 9781605981758.

- Bell, Howard (1969). A Survey of the Negro Convention Movement −1830-1861. New York: Arno Press. p. 10.

- Ernest, John (2011). A Nation Within a Nation: Organizing African-American Communities Before the Civil War. Ivan R Dee. p. 107. ISBN 9781566638074.

- Bell, Howard (1969). "1830, "Proceedings of the Convention," Philadelphia, PA" (PDF). Minutes and Proceedings of the National Negro Conventions, 1830–1864. New York: Arno Press. pp. 1–12.

- Harper's Weekly: 786. December 16, 1865. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Harper's Weekly: 81–82. February 6, 1869. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Yee, Shirley (April 1, 2011), National Negro Convention Movement (1831-1864), blackpast.org, retrieved September 2, 2020

- Hinton, R[ichard] J[osiah] (June 1889). "John Brown and his men, before and after the raid on Harper's Ferry, October 16th, 17th, 18th, 1859". Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly. 2 (6): 691–703, at pp. 695–696.

- Rondinone, Troy. "Colored National Labor Union". Encyclopedia of American History: Civil War and Reconstruction, 1856 to 1869, Revised Edition, vol. V. Archived from the original on April 18, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- "Today in Labor History: Black workers form national union". December 6, 2012. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- Harper's Weekly: 378. May 28, 1887. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

External links

- ColoredConventions.org includes PDFs of antebellum and post-bellum convention minutes, teaching resources, online exhibits and a critical bibliography.

- Digital Public Library of America. Items related to colored conventions, various dates