Coining press

A coining press is a manually operated machine that mints coins from planchets. After centuries it was replaced by more modern machines.

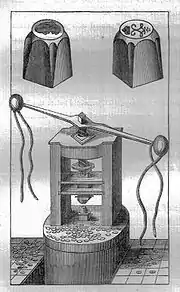

Presses came in multiple shapes and with different accessories (to collect the coins, etc.) They were made of cast iron. The basic elements are:[1][2][3]

- A triumphal arch with a built-in base

- A vertically arranged leadscrew that supported an inertia wheel or more commonly, a piece made up of two radial arms with weights at the ends.

- The leadscrew (male) rotates inside a threaded (female) nut. The nut is attached to the structure. The turn of the inertia wheel (or bar with weights) determines the rotation of the thread bar and its vertical displacement (up or down depending on the direction of rotation).

- Vertical guides allow vertical displacement of the holder (upper die) without rotating.

Operation

Each coin is formed in a single operation. The press holds two negatives (molds that show each side of the coin) The body (material from which the coin is to be formed) is placed on the lower negative and the upper negative is lowered to create pressure sufficient to emboss the negatives onto the body. The upper negative descends directly without turning, pushed by a threaded bar that rotates, turned by a lever, compensated by an anti-torsion system. It is called a cold deformation as not heat is applied.[4]

History

Before the press, coins were minted with a hammer:

After this, the "flam" were distributed to the moneyers to have the impressions put on them. Each moneyer had two irons or puncheons, one of which was called the "pile” and the other the “ Trussell” The "pile” was from seven to eight inches long and was firmly fixed in a block of wood (called "ceppeau ' in the French Ordonnances). On the pile” was engraved one side of the coin, and on the " Trussell,” the other. The “flan "being placed on the “pile" the " Trussell" was applied to the upper side of it by means of a twisted wand, or by the hand, and the moneyer then struck the end of the puncheon with the hammer until the impression was produced on the "flan.[4]

Gallery

References

- Joaquim Botet i Sisó; Joaquim Botet y Sisó (1997). Obra numismàtica esparsa i inèdita de Joaquim Botet i Sisó. Institut d'Estudis Catalans. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-84-7283-379-1.

- Notícia del volum tercer del "Tratado de las monedas labradas en el Principado de Cataluña por el Dr. D. Josef Salat"

- Jean Boizard (1711). Traité des monoyes, de leurs circonstances & dépendances. Chez Jacques Le Febvre. p. 145.

- Robert William Cochran-Patrick (1876). Records of the Coinage of Scotland: From the Earliest Period to the Union. Edmonstron and Douglas. pp. 49–.

- Irish Milled Coins.

- -en-scene-sa-mecanique-et-son-remplacement / La frappe au balancier monétaire (with the French terminology of a press).

- Vista de la casa de moneda cantonal. Cartagena Ilustrada. Año 1874. Año III. Número 31. Página 123.

Bibliography

- Burke, James (1985). The Day The Universe Changed. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 12049817.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cribb, Joe; Cook, Barrie; Carradice, Ian (1990). The Coin Atlas. New York: Facts on File. OCLC 19456971.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- de la Portilla, J.M. & Ceccarelli, Marco, eds. (2011). History of Machines for Heritage Engineering Development. New York: Springer. OCLC 729875665.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grier, John A. (January–June 1898). "A Familiar Chat About Our Mints". Modern Machinery: A Monthly Journal of Mechanical Progress. Chicago: Modern Machinery Publishing. 3: 326. OCLC 1713651. Retrieved July 14, 2014 – via Google Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Linecar, Howard (1971). Coins and Coin Collecting. Feltham, New York: Hamlyn. OCLC 667688.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Porteous, John (1969). Coins In History. New York: Putnam. OCLC 44608.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Price, Martin Jessop, ed. (1980). "The Nature of Coinage". Coins: An Illustrated Survey. New York: Methuen. OCLC 6194437.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yeoman, R. S. (1980). Bressett, Kenneth (ed.). 1981 Handbook of United States Coins with Premium List (38th ed.). Racine, Wisconsin: Western Publishing. OCLC 754090776.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2007). ——— (ed.). A Guide Book of United States Coins (61st ed.). Atlanta: Whitman. OCLC 123445484.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coining presses. |

_01.jpg.webp)