Codex Boernerianus

Codex Boernerianus, designated by Gp or 012 (in the Gregory-Aland numbering), α 1028 (von Soden), is a small New Testament codex, measuring 25 x 18 cm, written in one column per page, 20 lines per page. It is dated paleographically to the 9th century.[1] The name of the codex derives from the theology professor Christian Frederick Boerner, to whom it once belonged. The manuscript is lacunose.

| New Testament manuscript | |

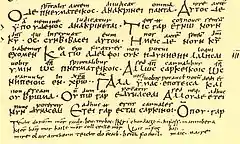

.jpg.webp) First page of the codex with lacunae in Romans 1:1-4 | |

| Name | Boernerianus |

|---|---|

| Sign | Gp |

| Text | Pauline epistles |

| Date | 850-900 |

| Script | Greek/Latin diglot |

| Found | Abbey of St. Gall, Switzerland |

| Now at | Saxon State Library Dresden |

| Cite | A. Reichardt, Der Codex Boernerianus. Der Briefe des Apostels Paulus, Verlag von Karl W. Hiersemann, Leipzig 1909. |

| Size | 25 x 18 cm |

| Type | Western |

| Category | III |

| Note | Irish verse on folio 23v. |

Description

The manuscript contains the text of the Pauline epistles (but does not contain Hebrews) on 99 vellum leaves. The main text is in Greek with an interlinear Latin translation inserted above the Greek text (in the same manner as Codex Sangallensis 48).

The text of the codex contains six lacunae (Romans 1:1-4, 2:17-24, 1 Cor. 3:8-16, 6:7-14, Col. 2:1-8, Philem. 21-25). Quotations from the Old Testament are marked in the left-hand margin by inverted commas (>), and Latin notation identifies a quotation (f.e. Iesaia). Capital letters follow regular in stichometric frequency. This means codex G was copied from a manuscript arranged in στίχοι. The codex sometimes uses minuscule letters: α, κ, ρ (of the same size as uncials). It does not use Spiritus asper, Spiritus lenis or accents.[2]

The Latin text is written in minuscule letters. The shape of Latin letters: r, s, t is characteristic of the Anglo-Saxon alphabet.

The Codex does not use the phrase ἐν Ῥώμῃ (in Rome). In Rom 1:7 this phrase was replaced by ἐν ἀγαπῃ (Latin text – in caritate et dilectione), and in 1:15 the phrase is omitted (in both Greek and Latin).

After the end of Philemon stands the title Προς Λαουδακησας αρχεται επιστολη (with interlinear Latin ad Laudicenses incipit epistola), but the apocryphal epistle is lost.[3]

Text

The Greek text of this codex is a representative of the Western text-type. Aland placed it in Category III.[1]

The section 1 Cor 14:34-35 is placed after 1 Cor 14:40, just like other manuscripts of the Western text-type (Claromontanus, Augiensis, 88, itd, g, and some manuscripts of Vulgate.[4][5]

The Latin text has some affinity with Liber Comicus.[6]

- Romans 6:5 αλλα και της αναστασεως ] αμα και της αναστασεως

- Romans 12:11 κυριω ] καιρω

- Romans 15:31 διακονια ] δωροφορια — B D Ggr

- Romans 16:15 Ιουλιαν ] Ιουνιαν — C.[7]

- Galatians 6:2 αναπληρωσατε ] αναπληρωσετε — B 1962 it vg syrp,pal copsa,bo goth eth[8]

- Philippians 3:16 τω αυτω στοιχειν ] το αυτο φρονειν, τω αυτω συνστοιχειν — supported by F[9]

- Philippians 4:7 νοηματα ] σωματα — F G[10]

In Romans 8:1 it reads Ιησου (as א, B, D, 1739, 1881, itd, g, copsa, bo, eth). The Byzantine manuscripts read Ιησου μη κατα σαρκα περιπατουσιν αλλα κατα πνευμα.[11]

It does not contain the ending Romans 16:25-27, but it has blanked space at Romans 14:23 for it.[12]

In 1 Corinthians 2:1 it reads μαρτυριον along with B D P Ψ 33 81 104 181 326 330 451 614 629 630 1241 1739 1877 1881 1962 1984 2127 2492 2495 Byz Lect it vg syrh copsa arm eth. Other manuscripts read μυστηριον or σωτηριον.[13]

In 1 Corinthians 2:4 it reads πειθοις σοφιας (plausible wisdom) along with 46. The Latin text supports reading πειθοι σοφιας (plausible wisdom) – 35 and Codex Augiensis (Latin text).[13]

In 2 Corinthians 2:10 the Greek text reads τηλικουτου θανατου, along with the codices: א, A, B, C, Dgr, K, P, Ψ, 0121a, 0209, 0243, 33, 81, 88, 104, 181, 326, 330, 436, 451, 614, 1241, 1739, 1877, 1881, 1962, 1984, 1985, 2127, 2492, 2495, Byz.[14]

The Old Irish Poem in the Codex Boernerianus

On folio 23 verso at the bottom is written a verse in Old Irish which refers to making a pilgrimage to Rome:

Téicht doróim

mór saido · becc · torbai ·

INrí chondaigi hifoss ·

manimbera latt nífogbái ·

Mór báis mor baile

mór coll ceille mor mire

olais airchenn teicht dó ecaib ·

beith fo étoil · maíc · maire ·

Stokes and Strachan's translation:[15]

To go to Rome, much labour, little profit: the King whom thou seekest here, unless thou bring him with thee, thou findest him not. Much folly, much frenzy, much loss of sense, much madness (is it), since going to death is certain, to be under the displeasure of Mary's Son.

Bruce M. Metzger in his book Manuscripts of the Greek Bible[16] quotes this poem, which seems to have been written by a disappointed pilgrim.[17]

History

The codex was probably written by an Irish monk in the Abbey of St. Gall, Switzerland between 850-900 A.D. Ludolph Kuster was the first to recognize the 9th century date of Codex Boernerianus.[18] The evidence for this date includes the style of the script, the smaller uncial letters in Greek, the Latin interlinear written in Anglo-Saxon minuscule, and the separation of words.[19]

In 1670 it was in the hands of P. Junius at Leiden.[20] The codex got its name from its first German owner, University of Leipzig professor Christian Frederick Boerner, who bought it in the Dutch Republic in the year 1705.[2] It was collated by Kuster, described in the preface to his edition of Mill's Greek New Testament. The manuscript was designated by symbol G in the second part of Wettstein's New Testament.[21] The text of the codex was published by Matthaei, at Meissen, in Saxony, in 1791, and supposed by him to have been written between the 8th and 12th centuries.[22] Rettig thought that Codex Sangallensis is a part of the same book as the Codex Boernerianus.[23]

During World War II, the codex suffered severely from water damage. Thus, the facsimile, as published in 1909, provides the most legible text. Some scholars believe that, originally, this codex formed a unit with the Gospel manuscript Codex Sangallensis 48 (Δ/037). Boernerianus is housed now in the Saxon State Library (A 145b), Dresden, Germany, while Δ (037) is at Saint Gallen, in Switzerland.[3][24]

References

- Aland, Kurt; Aland, Barbara (1995). The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism. Erroll F. Rhodes (trans.). Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-8028-4098-1.

- Gregory, Caspar René (1900). Textkritik des Neuen Testaments. 1. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung. p. 112.

- Metzger, Bruce M.; Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption and Restoration (4 ed.). New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-19-516122-9.

- NA26, p. 466.

- Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft: Stuttgart, 2001), pp. 499-500.

- A. H. McNeile, An Introduction to the Study of the New Testament, revised by C. S. C. Williams, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1955, p. 399.

- UBS3, p. 575.

- UBS3, p. 661.

- UBS4, p. 679.

- NA26, p. 521.

- UBS3, p. 548.

- UBS3, p. 577.

- UBS3, p. 581.

- UBS3, p. 622.

- Stokes, Whitley; Strachan, John, eds. (1903). Thesaurus Palaeohibernicus. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 296.

- Metzger, B. M. (1981). Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Palaeography. Oxford University Press. p. 104.

- Scrivener, Frederick Henry Ambrose; Edward Miller (1894). A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament. 1 (4 ed.). London: George Bell & Sons. p. 180.

- Alexander Reichardt (1909). Der Codex Boernerianus. Der Briefe des Apostels Paulus. Leipzig: Verlag von Karl W. Hiersemann. p. 9.

- Victor Gardthausen, Griechische Paläographie (Greek Paleography). Leipzig 1879. p. 271, 428 and 166; see also. H. Marsh, Comments. . to J. D. Michaelis' Introduction. I. p. 263

- C.v. Tischendorf, Editio octava critica maior, p. 427.

- Alexander Chalmers, The General biographical dictionary (London 1812), Vol. 4, pp. 508-509.

- Ch. F. Matthaei, XIII epistolarum Pauli codex Graecus cum versione latine veteri vulgo Antehieronymiana olim Boernerianus nunc bibliothecae electoralis Dresdensis, Meissen, 1791.

- H. C. M. Rettig, Antiquissimus quattuor evangeliorum canonicorum Codex Sangallensis Graeco-Latinus intertlinearis, (Zurich, 1836).

- "Liste Handschriften". Münster: Institute for New Testament Textual Research. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

Further reading

- Peter Corssen, Epistularum Paulinarum Latine Scriptos Augiensem, Boernerianum, Claromontanum, Jever Druck von H. Fiencke 1887-1889.

- W. H. P. Hatch, On the Relationship of Codex Augiensis and Codex Boernerianus of the Pauline Epistles, Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, Vol. 60, 1951, pp. 187–199.

- Alexander Reichardt, Der Codex Boernerianus. Der Briefe des Apostels Paulus, Verlag von Karl W. Hiersemann, Leipzig 1909.

- Bruce M. Metzger, Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Palaeography, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1981, pp. 104–105.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Codex Boernerianus. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- INTF. "Codex G/012 (GA)". Liste Handschriften. Münster Institute. Retrieved 2013-01-15.

- Codex Boernerianus Gp (012) at the CSNTM (images of the 1909 facsimile edition)

- Codex Boernerianus Gp (012) recently made photos at SLUB Dresden Digitale Bibliothek

- Codex Boernerianus recently made photos at SLUB Dresden Digitale Bibliothek (PDF)

- Manuscript Gp (012) at the Encyclopedia of Textual Criticism