Citizens' initiative referendum (France)

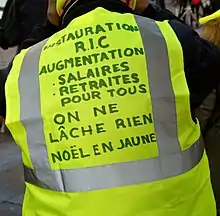

The Référendum d'initiative Citoyenne (abbreviated RIC) is the name given to the proposal for a constitutional amendment in France to permit consultation of the citizenry by referendum concerning the proposition or abrogation of laws, the revocation of politicians' mandates, and constitutional amendment.[2]

The proposed process is a direct democracy mechanism that allows citizens to petition for a referendum without needing the consent of the parliament or president. Similar referendums are used in around forty other countries, including Italy, Switzerland, Taiwan, Venezuela, New Zealand and in the US state of Oregon.

History of the idea in France

In Manifeste au service du personnalisme (1936), Emmanuel Mounier proposed that popular-initiative referenda should counterbalance the parliamentary will in periods between elections. In the 1981, the idea was part of the platform for two Left presidential candidates: Huguette Bouchardeau (United Socialists Party) and Brice Lalonde. In 1983, Charles Pasqua (RPR) introduced a bill in the Senate and in 1987 Yvan Blot (RPR) introduced one in the lower house to permit popular-initiative referenda.[3]

Types of referendums

Citizens' initiative referendums around the world are based on petitions. To have an effect, a sufficient number of signatures must be gathered within a given time period. In France, these four types of popular referenda are being proposed: legislative (propose a law), abrogatory (repeal a law), recall (revoke the mandate of a sitting politician), and constitutional amendment.

In France, yellow vests propose that these referendums should be applicable to four types of procedures:[1]

- the legislative referendum, which would consist in submitting a bill to the people.

The modalities for implementing this type of referendum vary significantly from one country to another. In Taiwan, for example, the signatures of 0.01 and then 1.5% of the population registered on the electoral rolls, collected over a six-month period, make it possible to trigger a referendum on a proposed law. The result, if positive, must reach a quorum of 25% of the registered members to be legally binding.[4][5][6] In contrast, in New Zealand, the signatures of 10% of registrants are required within a year, and the result is not legally binding.[7]

- the abrogatory referendum, which would consist of the possibility for the population to repeal or prevent the implementation of a law previously passed by Parliament.

Being able to oppose the entry into force of a new law is an existing possibility in several countries, including Italy, Slovenia, Uruguay, Taiwan, Switzerland or Liechtenstein. In the latter two, it is known as optional referendum.

- the recall referendum, which would consist in dismissing an elected representative from office.

This procedure exists in very few countries at the national level: at the local level, in some states of the United States as well as in several countries in the Americas, including Peru, where it has become commonplace. At the national level, only Ecuador and Venezuela allow it against the Head of State through a popular initiative. In Venezuela, a consultation can only be held once half of the presidential term has elapsed, requires the signatures of 20% of those registered, and is validated by referendum only by a higher number of votes for revocation than the one obtained by the president during his election, provided that a quorum of 25% of the vote is also reached. In Ecuador, the signatures of 15% of those registered within six months are required. An absolute majority of the voters is sufficient, but it cannot be organised during the first or last year of the elected representative. In both cases, it can only be organised once per mandate.[8]

- the constitutional referendum, which would consist in allowing the people to amend the country's Constitution. Currently, according to Article 89 of the French Constitution, the initiative for such an amendment is concurrently the responsibility of the President of the Republic, on a proposal from the Prime Minister, and the members of Parliament. After the draft or proposed revision has been voted on in identical terms by both assemblies, the text shall be submitted to a referendum for approval unless the President of the Republic submits it to Parliament in Congress, in which case the draft revision shall not be approved unless it is approved by a qualified majority of three fifths of the votes cast.

The importance of a constitutional change means that few countries allow it to have a popular origin, or subject it to stricter conditions. In Uruguay, the collection of signatures from ten per cent of registered voters makes it possible to hold such a referendum, but it is only valid if the "yes" vote receives an absolute majority and at least 35 per cent of the total number of registered voters, which implies a participation of at least 70 per cent. In 2004, Uruguayans used this mechanism to enshrine the right to water and sanitation in their constitutions.[9][10]

Support and criticism

For supporters of the recall referendum, if elected officials are revocable, they will no longer be able to betray their campaign promises with impunity, which could also reduce abstention.[8]

Some personalities criticize the very principle of repeal or revocation referendums, considering that they represent a danger of instability or paralysis and would thus hinder the freedom of action of elected representatives by imposing on them an imperative mandate which is nevertheless contrary to the principle of Article 27 of the Constitution of the Fifth French Republic.[8] Some criticize these proposals as «poujadism», or as demagogy.[11]

See also

References

- "Référendum d'initiative citoyenne : quels modèles étrangers inspirent les "gilets jaunes" ?".

- Zoé Lauwereys (10 December 2018). "Qu'est-ce que le RIC, ce référendum que réclament les Gilets jaunes ?". Le Parisien.

- Laurent de Boissieu (20 December 2018). "Le RIC, de la gauche autogestionnaire à l'extrême droite". La Croix (in French). Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Shih, Hsiu-chuan; Liu, Li-jung (12 December 2017). "Referendum amendment passage makes people masters: president". Central News Agency. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- Lin, Sean (13 December 2017). "Referendum Act amendments approved". Taipei Times. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- Art. 29 of the referendum law

- Citizens Initiated Referenda Act 1993

- "Le RIC, référendum d'initiative citoyenne, une solution à la crise des "gilets jaunes" ?". le Figaro. 11 December 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Carlos Santos; Alberto Villareal (30 September 2010). "Uruguay : l'usage de la démocratie directe pour défendre le droit à l'eau" (in French). Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Beat Müller. "Uruguay, 31. Oktober 2004 : Wasserversorgung in Staatsbesitz". Database and Search Engine for Direct Democracy (in German).

- Laure Equy; Rachid Laïreche (18 December 2018). "Corbière-Houlié : l'amour du RIC (et ses limites)". Libération (in French). Retrieved 7 January 2019.