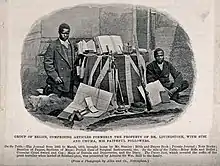

Chuma and Susi

James Chuma and Abdullah Susi were people from central Africa who attended to and accompanied the explorer David Livingstone.

_(14776237225).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Status

James Chuma and Abdullah Susi came to attention after their employer Livingstone died at Chitambo's village (in modern-day Zambia). They decided to carry his body all the way to Bagamoyo (on the coast of modern-day Tanzania) where it was handed over to the British authorities and transported to London for burial.

Background

Chuma was only a boy when David Livingstone and Bishop Charles MacKenzie freed him from slavers in 1861, when he was around 11 years old.[1] From that day Livingstone became his only "family".

Susi joined Livingstone at Chupanga in present-day Mozambique when he was employed to cut wood on Livingstone's "Second Journey".[1] He accompanied Chuma on their epic march to return Livingstone's body, and accompanied Livingstone's remains to England. He afterwards served in mission work in the Nyassa country.

Both Chuma and Susi were presented with a Royal Geographical Society medal on 22 June 1874.[2]

James Chuma

James Chuma (also written as Juma), was born to Chimilengo, who was a fisherman by profession.[3] He was from the Yao people, and probably came from present day Mozambique or Malawi. He was baptised as James Chuma on 10 December 1865 by John Wilson, with David Livingstone present.[4]

Chuma accompanied Joseph Thomson on the Royal Geographical Society’s 1878-80 East African Expedition.[5] He married in 1874, a year after the death of Livingstone.[6] He worked with UMCA from 1875 to 1878[7]

Chuma died towards the end of 1882 of tuberculosis.[8]

Abdullah Susi

Abdullah Susi met Livingstone in 1863 when he was employed to help build the Lady Nyasa; he then sailed to Bombay where he was left by Livingstone and enrolled in Dr Wilson's Free State College.[9]

When Livingstone returned he recruited Susi as a porter for his last journey in 1866-74 to find the source of the Nile.[10]

It was Susi who first noticed the approach of Henry Stanley, when he heard the shots signalling their approach he ran to Stanley, who says

"Suddenly a man - a black man - at my elbow shouts in English, 'How do you do, sir?' 'Hello! Who the deuce are you?' 'I am the servant of Dr Livingstone', he says; but before I can ask any more questions he is running like a madman towards the town"[11]

When Livingstone died in 1873 Susi, Chuma and others of the party debated what to do with the body - arrangements were made for drying and embalming the body after removing the heart for burial under a mvula tree, then undertook the long journey to the coast to return the embalmed body to the UK.[12]

Although Susi and Chuma did not travel with the body from Africa or attend the funeral they were invited by James Young later in 1874 to come to Britain with a view to helping Horace Waller to edit Livingstone's last journals for publication. While in the UK they stayed at Newstead Abbey, home of Livingstone's friend William Webb. They returned to Africa in October the same year.

Back in Africa Susi went on to take part in further expeditions including the one led by Stanley in 1879-82.[13] Originally Muslim, Susi was baptised as a Christian on 23 August 1886 under the name David. He married Mochosi and died 5 May 1891 in Zanzibar.[14]

Like the other followers who accompanied Livingstone on the last journey and carried his body to the coast, Susi was awarded a medal by the Royal Geographical Society in 1874.[15]

References

- David Livingstone and Horace Waller (ed.): The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa from 1865 to his Death. Two Volumes. John Murray, London, 1874.

- Kirk-Greene, A.H.M. (1978). "Review: Dark Companions. By DONALD SIMPSON. London: Paul Elek, 1975. Pp. xi, 228, ill., bibl. £7.50". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 48:2: 191–192.

- Pettitt, Clare (2007). Dr. Livingstone, I Presume?: Missionaries, Journalists, Explorers, and Empire. ebook: Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-67402-487-8.

- Pettitt, Claire (2013). Dr Livingstone I Presume: Missionaries, Journalists, Explorers and Empire. London: Profile Books. p. 156.

- Thomson, Joseph (1880). "'Journey of the Society's East African Expedition'". Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography. 2:12: 721–742.

- Pettitt, Clare. Dr Livingstone I Presume: Missionaries, Journalists, Explorers and Empire.

- Pettitt, Clare. Dr Livingstone I Presume: Missionaries, Journalists, Explorers and Empire.

- Simpson, Donald (1975). The Dark Companions. London: Paul Elek. p. 56.

- Pettitt, Clare (2007). Dr Livingstone I presume. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674024878.

- Simpson, Donald Herbert. (1975). Dark companions : the African contribution to the European exploration of East Africa. London: Elek. p. 89. ISBN 0236400061. OCLC 2930820.

- Bennett, N. R. (1970). Stanley's Despatches to the New York Herald. Boston: Boston University Press. pp. 89.

- Blaikie, William Garden (1880). The Personal Life of David Livingstone. London: John Murray. pp. 446–7.

- Simpson, Donald Herbert. (1975). Dark companions : the African contribution to the European exploration of East Africa. London: Elek. p. 197. ISBN 0236400061. OCLC 2930820.

- Simpson, Donald (1975). Dark Companions. London: Paul Elek Ltd. p. 197. ISBN 0-236-40006-1.

- Simpson, Donald (1975). Dark Companions. London: Paul Elek Ltd. pp. 191, 197. ISBN 0-236-40006-1.