Chola Navy

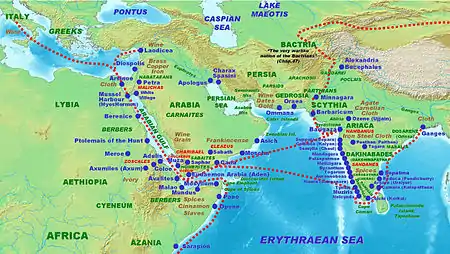

The Chola Navy (Tamil: சோழர் கடற்படை; Transliteration: Cōḻar kadatpadai) comprised the naval forces of the Chola Empire (4th Century BCE – 1279 CE), a Tamil thalassocratic empire of southern India, one of the longest-ruling dynasties in the world. The Chola Navy grew in size and status during the Medieval Cholas reign. Between 900 and 1100 CE, the navy grew from a small backwater entity to a potent maritime and diplomatic force across Asia, with maritime trade links extending from Arabia to China.

| Chola Navy | |

|---|---|

| Kappalpadai | |

Depiction of the siege of Kedah, the battle between Beemasenan's Chola naval infantry and the defenders of Kedah fort. | |

| Founded | 3rd century CE |

| Country | Chola Empire |

| Allegiance | Chola Dynasty |

| Branch | Naval |

| Type | Naval Force |

| Size | ~1 million men, 600–1000 warships (at peak strength) |

| Part of | Chola military |

| Engagements |

|

| Commanders | |

| Ceremonial chief | Chola Emperor (Chakravarthy) – notably, Rajaraja I and Rajendra I |

| Notable commanders |

|

The Cholas were at the height of their power from the latter half of the 9th century CE through the early 13th century CE.[1]:5 Under Rajaraja Chola I (reign c. 985 – c. 1014), Chola territories in South Asia stretched from the Maldives to the banks of the Godavari River in Andhra Pradesh.[2] Between 1010 and 1153 CE, Rajaraja's successors continued the expansion, making the Chola Empire a military, economic and cultural power in South and South-East Asia.[3]:215 During this period, the Chola Navy helped expand the empire with Naval expeditions to the Pala of Pataliputra, along the Ganges and the Chola invasion of Srivijaya (present-day Indonesia) in 1025 CE,[4] as well as repeated embassies to China.[1]:158 The Chola Navy declined in the 13th century when the Cholas fought land battles with the Chalukyas of Andhra-Kannada area in South India, and with the rise of the Pandyan dynasty.[1]:175

The Chola fleet represented the zenith of ancient Indian sea power. At its peak, the Chola Navy was Asia's largest navy, with blue-water capabilities, and a personnel strength of a million men.[5] This multi-dimensional force enabled the Cholas to achieve the Military, Political and cultural hegemony over a vast maritime empire stretching from the Maldives to The Philippines and North India, and trade links stretching from Rome to China. The Chola naval influence resulted in a lasting legacy of Indic cultural influences on language, art, architecture, and religion in Southeast Asia, evidenced in Balinese Hinduism and Cham culture (see Hinduism in Southeast Asia).

History

Historians divide the Chola dynastic rule into three distinct phases: The Early Cholas (c. 4th century BCE – 200 CE), the Medieval or Vijalaya Chola period (848 – 1070 CE), and the Chalukya Chola period (1070 – 1279 CE). The interregunum period between 200 and 848 CE is not well documented, although it is believed that the Chola dynasty continued to rule a diminished kingdom around Uraiyur.

Under Rajaraja Chola I and his son Rajendra Chola I, the dynasty became a military, economic and cultural power in Asia.[6]:115[3]:215 During the period 1010–1200, the Chola territories stretched from the northernmost islands of the Maldives in the south to as far north as the banks of the Godavari River in Andhra Pradesh.[2] Rajaraja Chola conquered peninsular South India, annexed parts of Sri Lanka and occupied the islands of the northernmost atolls of the Maldives.[3]:215 Rajendra Chola sent a victorious expedition to North India that touched the river Ganges and defeated the Pala ruler of Pataliputra, Mahipala. He also successfully raided kingdoms of Maritime Southeast Asia.[lower-alpha 1][7]:211–220[4]

Early Chola Period (c. 4th century BCE – 200 CE)

The Cholas were mentioned in Ashokan Edicts of 3rd Century BCE (located in modern Delhi) as one of the neighboring kingdoms in the South.[8] The earliest mention of specific Chola rulers is found in Sangam literature (c. 100 BCE – 250 CE).[9] The Mahavamsa mentions a Chola prince known as Ellalan invading and conquering Sri Lanka around 235 BCE with the help of a Mysore army.[10][11]

Direct maritime trade between India and the Romans and Greeks began with Augustus' conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE, and the rise of the Ptolemaic dynasty.[12] Roman Egypt built on the existing trade with India from Arab ports, through the harbour of Arsinoe, the present day Suez, and Alexandria.[12][13] Roman and Greek traders frequented the ancient Tamil country, securing trade with the seafaring Tamil states of the Pandyan, Chola and Chera dynasties and establishing trading settlements.

The main centers of trade with the Cholas were the regional ports of Kaveripattinam and Arikamedu, along with the inland city of Kodumanal.[14] The Periplus of the Erythrean Sea mentions a marketplace named Poduke (ch. 60), which G.W.B. Huntingford identified as possibly being Arikamedu (now part of Ariyankuppam), about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from the modern Pondicherry.[15] Huntingford further notes that Roman pottery was found at Arikamedu in 1937, and archaeological excavations between 1944 and 1949 showed that it was "a trading station to which goods of Roman manufacture were imported during the first half of the 1st century AD".[15]

The earliest specific reference to the Chola navy by an external source comes from a 1st-century Roman report of Kaveripoompattinam (presently known as Poombuhar) as Haverpoum and a description of how the Trade vessels were escorted by the King's fleet to the estuary as it was a natural harbor in the mouth of the river Kaveri.[16] Archaeological evidence of maritime activities of this era include some excavated wooden plaques depicting naval engagements in the vicinity of the old city (See Poompuhar for more details).

Much insight into the Chola naval activity has been gathered from Periplus, which describes the activity of escort ships assigned to merchant vessels with valuable cargo.[14] The Periplus describes 'great ships' (called 'Colandia' ) sailing to pacific islands from three ports in 'Damirica' , with Kaveripattinam as the centre.[17] Pattinathu Pillai is named as the chief of the Chola Navy during that period.[18] These early naval ships are described as having some sort of a rudimentary flame-thrower and/or a catapult type weapon.[19]

Interregnum Period (200–848 CE)

Little is known about the transition period of around three centuries from the end of the Sangam age (c. 300) up to the time when the Pandyas and Pallavas dominated the Tamil country (c. 600). An obscure dynasty, the Kalabhras, invaded the Tamil country, displaced the existing kingdoms and ruled for around three centuries. They were displaced by the Pallavas and the Pandyas in the 6th century.

This period from the 3rd century until the 7th century is a blind spot in the maritime tradition of the Cholas. Little is known of the fate of the Cholas during the succeeding three centuries until the accession of Vijayalaya in the second quarter of the 9th century. In the Interregnum, the Cholas were probably reduced to Vassals of Pallavas, though at times they switched sides and allied with Pandyas and tried to dispose their overlords. But, there is no concrete line of kings or court recordings.

However, even during this time the Cholas had maintained a small but potent Naval force based inland in the Kaveri river. During this time they dominated the inland trade in the Kaveri basin with Musuri as a major inland port. Dry-docks built during this period exist to this day.[20] Accounts from Arab travellers of this period mention that ships in the Indian Ocean were made of wooden planks held together by coir ropes and not by iron spikes.[21]:266

Imperial Chola Period (848–1070 CE)

The Medieval Chola period is the most well-documented era in Chola history, partly due to the survival of the edicts and inscriptions from the time, along with reliable foreign narratives, allowing a clear picture of Chola Naval activity. The Medieval period saw a resurgence of Chola power, with the empire expand from a small, land-locked principality to the pre-eminent power in South India and Southeast Asia.

The Medieval Cholas assumed the mantle of maritime power from the Pallava dynasty, which declined in this period. Significant improvements were made to the Chola Navy in this period, transforming it from a small force to the largest Navy in Asia. The Chola naval fleet from 900 to 1150 CE consisted of between 600 and 1000 warships, and during the reigns of Rajaraja Chola I and Rajendra Chola I, had a manpower of over one million naval soldiers and sailors.[21]:268

848–950 CE

When Vijayalaya Chola (reign 848–870 CE) took the throne, the Chola kingdom was a small, land-locked principality around Uraiyur, sandwiched between the powerful Pallava kingdom of Kanchipuram to the north and the Pandyas to the south, ruling from Madurai. Access to the sea was possible through the Kaveri River. Capitalizing on a war between the Pallavas and the Pandyas, Vijayalaya captured Thanjavur and established the city as the Chola capital. His successor Aditya I (reign c.870–907 CE) successfully defended the kingdom against a Pandya invasion during the last years of Vijayalaya's reign, and conquered the weakened Pallava kingdom in 903 CE. It is unclear if the Chola navy was involved in significant action during these campaigns.

The Chola navy was significantly strengthened during the reign of Aditya I's son, Parantanka I (reign. 907–950 CE). Parantaka continued his father's campaigns to the south, and captured the Pandya capital of Madurai in 910 CE, and later overthrew the Pandya king, Maravarman Rajasinha III, inflicting a final defeat on a combined army of the Pandyas and their Sri Lankan allies at the Battle of Vellore. Following the pacification of Pandya territories, Parantaka embarked on the first significant naval campaign in the Medieval Chola period, a punitive invasion of Ceylon, annexing northern Ceylon.[21]:267

950–985 CE

The 35 years between Parantaka I and the ascension of Rajaraja Chola saw significant instability and intrigue in the Chola kingdom, with little documented naval activity. Internal dissension led to a resurgence of the Pandyas, and an increasingly tenuous hold on Chola territories in Ceylon. Parantaka Chola II (Sundara Chola) defeated another allied Pandyan-Ceylonese force at Chevur, near Pudukkottai in 959 CE, but did not manage to reconquer all Pandya territory. A second Cholan naval expedition against the Ceylon kingdom of Mahinda IV was also unsuccessful. Sundara Chola's heir-apparent, Aditya II was assassinated under mysterious circumstances, While unsuccessful in expanding the empire, Uttama managed to prevent territorial losses from the resurgent Rashtrakutas, as well as the Pandya-Ceylon alliance. He also initiated improvements to the armed forces, which were continued upon his death by his successor, Arulmozhi Varman, who would later be known by the reignal name Rajaraja Chola.

Imperial navy with blue-water capabilities

The evolution of combat ships and naval-architecture elsewhere played an important part in the development of the Pallava Navy. There were serious efforts in the period of the Pallava king Simhavishnu to control the piracy in South East Asia and to establish a Tamil friendly regime in the Malay peninsula. However, this effort was accomplished only three centuries later by the new Naval power of the Cholas.

The three decades of conflict with the Sinhalese King Mahinda V came to a swift end, after Raja Raja Chola I's (985–1014) ascent to the throne and his decisive use of the naval flotilla to subdue the Sinhalese.

This period also marked the departure in thinking from the age-old traditions. Rajaraja commissioned various foreigners (Prominently, the Arabs and Chinese) in the naval building program.[22] These effort were continued and the benefits were reaped by his successor, Rajendra Chola I. Rajendra led a successful expedition against the Sri Vijaya kingdom (present day Indonesia) and subdued Sailendra. Though there were friendly exchanges between the Sri Vijaya empire and the Chola Empire in preceding times (including the construction of Chudamani Pagoda in Nagapattinam), the raid seems to have been motivated by commercial rather than political interests.

An inscription from Sirkazhi, dated to 1187 AD, mentions a naval officer called Araiyan Kadalkolamitantaan alias Amarakon Pallavaraiyan. He is mentioned as the Tandalnayagam of the Karaippadaiyilaar. The term Karaippadaiyilaar means forces or army of the seashore and the title Tandalnayagam is similar to Dandanayaka and means commander of the forces. The title Kadalkolamitantaan means "one who floated while the sea was engulfed".[23]

Later Cholas

Trade, Commerce, and Diplomacy

The Cholas excelled in foreign trade and maritime activity, extending their influence overseas to China and Southeast Asia.[6]:116–117 A fragmentary Tamil inscription found in Sumatra cites the name of a merchant guild Nanadesa Tisaiyayirattu Ainnutruvar (literally, "the five hundred from the four countries and the thousand directions"), a famous merchant guild in the Chola country.[6]:118 The inscription is dated 1088, indicating that there was an active overseas trade during the Chola period.[6]:117

Towards the end of the 9th century, southern India had developed extensive maritime and commercial activity, especially with the Chinese and Arabs.[6]:12,118 The Cholas, being in possession of parts of both the west and the east coasts of peninsular India, were at the forefront of these ventures.[6]:124[24][25] The Tang dynasty of China, the Srivijaya empire in the Malayan archipelago under the Sailendras, and the Abbasid caliphate at Baghdad were the main trading partners.[7]:604

The trade with the Chinese was a very lucrative enterprise, and Trade guilds needed the king's approval and the license from the customs force/department to embark on overseas voyages for trade.[26] The normal trade voyage of those day involved three legs of journey, starting with the Indian goods (mainly spices, cotton and gems) being shipped to China and in the return leg the Chinese goods (silk, incense,iron) were brought back to Chola ports. After some materials were utilized for local consumption, the remaining cargo along with Indian cargo was shipped to the Arabs. Traditionally, this involved transfer of material/cargo to many ships before the ultimate destination was reached.

Combating Piracy in Southeast Asia

The Strategic position of Sri Vijaya and Khamboj (modern-day Cambodia) as a midpoint in the trade route between Chinese and Arabian ports was crucial. Up to the 5th century, the Arabs traded with Chinese directly using Sri Vijaya as a port of call and replenishment hub. Realizing their potential, the Sri Vijaya empire began to encourage the sea piracy surrounding the area.[27] The benefits were twofold, the loot from piracy was a good bounty and it ensured their sovereignty and cooperation from all the trading parties.[27] Piracy also grew stronger due to a conflict of succession in Sri Vijaya, when two princes fought for the throne and in turn, relied on the loot from the sea-piracy for their civil war.[27]

The pirate menace grew to unprecedented levels. Sea trade with China was virtually impossible without the loss of a third of the convoy for every voyage. A troubling and previously unseen development was attacks even on escorted convoys. Repeated diplomatic missions urged the Sri Vijaya empire to curb the piracy, with little effect. With the rise in piracy, and in the absence of Chinese commodity, the Arabs, on whom the Cholas were dependent of horses for their cavalry corps, began to demand higher prices for their trade, leading to a slew of reductions in the Chola army.[28] The Chinese too were infuriated by the piracy menace in the Melaccas.

In response, the Cholas embarked on their most significant naval campaign, the 1st Expedition of the Chola Navy into the Malay peninsula.[29] In one particular instance, the Cholas went as far as to conquer Kamboja (modern-day Cambodia) and gave it to the Sri Vijaya kings (as per their request) to ensure cooperation in the curbing piracy.

Cooperation with the Chinese

Chinese Song Dynasty reports record that an embassy from Chulian (Chola) reached the Chinese court in the year 1077,[6]:117[3]:223[30] and that the king of the Chulien at the time was called Ti-hua-kia-lo.[7]:316 It is possible that these syllables denote "Deva Kulo[tunga]" (Kulothunga Chola I). This embassy was a trading venture and was highly profitable to the visitors, who returned with '81,800 strings of copper coins in exchange for articles of tributes, including glass articles, and spices'.[lower-alpha 2][1]:173

The close diplomatic tie between the Song dynasty of China and the Medieval Cholas facilitated many technological innovations to travel both ways. The more interesting ones to have reached Chinese shores are:

- The famous Chola ship-designs employing independent water tight compartments in the hull of a ship.

- The mariner's compass

- The continuously shooting flamethrowers for naval warfare.[31]

Organization and administration

The extent of the Chola empire necessitated that the Navy possess capabilities in riverine, littoral, and open-ocean naval combat, as well as large-scale expeditionary capabilities. A sophisticated and diversified force, the Chola Navy was able to carry out both combat and non-combat capabilities, including escorting trade convoys and friendly vessels, patrolling and anti-piracy interdiction, sabotage of enemy ships, naval combat in river basins, and land assault by establishing beachheads.

Ports and fleets

The oldest and most famous port in the Chola Empire was Poompuhar. Other naval ports were located at Arikamedu, Kancheepuram, Nagapattinam, Kulachal, Korkai, Kadalur, and Thoothukudi. In addition to these sea ports, there were many inland ports, such as Musuri and Worayur (or Urayur) and dry docks navigable from the sea along the Kaveri and Thamarabarani rivers which served commercial fleets and shipbuilding. In times of war, to facilitate mass production, ships were built inland and ferried through the rivers to the Ocean.

Administration

The king/emperor was the supreme commander of all the military forces including the navy. The operational responsibilities were conducted by Admirals of the Pirivu-Athipathy and Ganathipathy ranks. Chola Admirals commanded much respect and prestige in society, and were given a free hand in recruiting and training of sailors, engineers, oarsmen and marines. Recruitment was egalitarian; any citizen or even non-citizen could join the navy, although it is unclear if they would be assigned their preferred duties. During the early period of the Chola Navy, preference was given to retired soldiers and sailors, their sons, and noblemen. However, this attitude changed in later days and many soldiers and sailors distinguished themselves, irrespective of rank and social class.

Rank structure

Due to the presence of both Naval and Marine infantry elements, the Chola Navy used a hybrid rank structure, with dedicated naval ranks as well as army-derived ranks.[32] The approximate rank hierarchy in the Chola Navy was:

- Chakravarthy : The Commander-in-Chief, i.e. the Chola Emperor

- Jalathipathi : The Chief of navy, roughly equivalent to the Secretary of the Navy.

- Tandalnayagam : The Commander of the Navy, roughly, equivalent to Admiral of the fleet.[33]

- Pirivu-Athipathy : Alternatively called Pirivu-Devar/Devan/Nayagan. The commander of a fleet, roughly equivalent to an Admiral

- Ganathipathy : The commander of a Taskforce, roughly the equivalent of a Vice Admiral

- Mandalathipathy : The commander of a group, the equivalent of a Rear Admiral

- Jalathalathipathi : The commander of a flotilla or fleet squadron, approximately equivalent to a Commodore

- Kalapathy : The commanding officer of a ship, equivalent to Captain in modern navies.

- Kaapu : Roughly performing the duties of the executive officer and weapons officer of a ship.

- Seevai : The officer in-charge of the oarsmen / masts, roughly the equivalent of the master chief and engineering officer.

- Eeitimaar : The officer in-charge of the marine boarding party. Equivalent to a captain or major.

Fleet Organization

The Imperial Navy of the Medieval Cholas was composed of a multitude of forces under its command. In addition to the regular navy (Kappalpadai), there were many auxiliary forces that could be used in naval combat as reserves or irregulars. Unlike many of its contemporaries, the Chola Navy was an autonomous service. The Army depended on the Naval-fleets for transportation and logistics. The navy also had a Marine Corps. Pearl fishermen were utilized as saboteurs to dive and disable enemy vessels by destroying or damaging the rudder.[31]

The Chola Navy had a sophisticated organisation structure, with multiple levels and battle group sizes depending on the operational requirements, akin to modern day Naval fleet organisation. This organisation became necessary after the conquest of Ceylon. The navy was organised into role-based squadrons and divisions, containing various ship types assigned for specific roles and home-ported at associated ports. A Ganam was typically the largest operational unit, consisting of between 100 and 150 ships of various types, and included a strong marine infantry presence.

During the reign of Rajaraja Chola I and Rajendra Chola I, the main navy (Kappalpadai) comprised five fleets – three fleets of warships, two fleets of logistics ships, as well as transport ships to serve the needs of the Army. The main war fleet was home ported in Nagapattinam, the second war fleet at Kadalur, and a smaller fleet based inland at Kanchipuram, along the Palar River. In later years, these numbers increased drastically. By the late 11th century, there were a total of nine battle fleets, based in various locations across the Chola empire, ranging from the present day Aceh, Angkor Wat, to the southern reaches of Ceylon. Fleets were usually named after past monarchs and gods. The most distinguished ones were granted Royal prefixes like Theiva.

Unit Hierarchy

| Unit Name | Commander | Modern equivalent | Composition | Functions | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kanni | Senior-Kalapathy (equivalent to a Commodore)[lower-alpha 3] | Division | Not more than five ships of any role | A special purpose, tactical formation, a kanni would lure enemy ships to a particular area where larger naval groups (usually, a Thalam) would wait in ambush. During a strategic deployment, the formation would be used many times as lure before engaging in combat with the main fleet. | [lower-alpha 4] [lower-alpha 5][34] |

| Jalathalam or simply, Thalam | Jalathalathipathy[lower-alpha 6] | Fleet-Squadron or Flotilla | 5 main battle vessels, 3 auxiliary vessels, 2 logistics vessels, and 1–2 Privateers. | Reconnaissance, patrol or interdiction. The thalam was the smallest self-sustained permanent formation in the Chola navy. Normally, 2–3 Thalam operated in sector, allowing them to search a wide area but remain close enough to quickly reinforce each other. | [lower-alpha 7] [lower-alpha 8] |

| Mandalam | Mandalathipathy | Roughly equivalent to Task force or Battle groups | 48 Ships of various roles | A semi-permanent formation, mostly used in expeditionary deployment. Used as individual combat units, especially during pincer or break-neck maneuvering in the high-seas. | [lower-alpha 9] |

| Ganam | Ganathipathy (equivalent to Vice-Admiral) | Taskforce or battle group | 3 mandalams (100–150 Ships of various roles) | A self-reliant, permanent unit of the force, only smaller than the Fleet, with combat, reconnaissance, logistics and resupply/repair units. | [lower-alpha 10] [lower-alpha 11] |

| Ani | Anipathy | Battle Fleet | 3+ ganams (300–500 ships) | A special expeditionary group, rarely used, and raised only for specific military campaigns. | [lower-alpha 12][35] |

| Pirivu | Commanded by a prince or confidante of the King, the title varies.[lower-alpha 13] | Fleet | They functioned much like modern Naval fleets. There were two to four fleets in the Chola navy during various times. The principal fleet was based in the east. Later, a second fleet was based in Ceylon. During and after the reign of Rajendra I, three or four fleets existed. | [lower-alpha 14] |

Auxiliary naval forces

In addition to the standing navy, other services which had their own naval arms, notably the Customs department, militia, and the state monopoly of pearl fisheries. In addition to the Kappalpadai, small but formidable irregular Naval forces were maintained by the trade guilds, which secured the trade convoys in their voyages. The auxiliary naval forces were highly regulated and acted as mercenaries and Naval reserves in times of need.[36]

Customs and Excise

The Customs force, called Sungu (Sunga Illaka) was highly organized, and largely operated as the Chola Empire's equivalent of a Coast Guard. Under the command of a Director-General officer, called Thalai-Thirvai (Thalai – Head, Thirvai – customs duty), the Sungu had various departments:[37]

| Department | Duties | Assets |

|---|---|---|

| Thirvai (Customs) | This unit employed merchants and economists who deduced and set the Customs duty rates for commodities for a particular season, based on economic factors. Trade-voyages were influenced by ocean currents and hence the price changed accordingly. | They typically had boarding officers, boarding crafts and some sea vessels as most of their responsibilities were inland. |

| Aaivu (Inspection and enforcement) | This unit was the enforcement arm of the customs department. They inspected ships for contraband or wrongly declared tonnage, investigated and policed small crimes, and protected the harbours. | Fast assault and boarding vessels. The Chola navy often sought its help in intercepting rogue vessels. |

| Ottru (Intelligence) | They were the intelligence corps of the territorial waters of the Chola dominion. They tailed foreign vessels, performed path-finding for larger forces or convoys and gave periodic updates for the kings and the trade guilds of the happenings in the sea. | They operated highly capable vessels designed for stealth and speed, equipped with concealed catapults and flame-throwers. Most of their vessels were privateered and contained no national markings. |

| Kallarani | Privateers under the seal of the Chole Empire were used in auxiliary roles to patrol the coastline, and to deal with piracy, especially in the Arabian Sea. | These mercenaries operated a variety of captured ships. Kallarani ships were commanded and crewed by sailors from many different countries and ethnic groups. Notable among them the Arabian Amirs, who were highly regarded for their loyalty and fervour in combat. |

| Karaipirivu | They performed duties akin to the modern coast-guard, search and rescue and coastal patrols. Their primary duties, however, were land-based, providing a seaward defense. | They operated substantially smaller crafts and occasionally, catamarans. |

Coast guard

In the late 12th century CE, the Chola navy was constantly battling in many fronts to protect commercial, religious and political interests across the empire. With the larger, more powerful ships being deployed in large numbers to reinforce and support the fleet in the high seas, the home ports were left relatively undefended. This led to a change in Chola naval strategy, leading to the development of a specialised auxiliary force with large numbers of fast and heavily armed light ships in large numbers. The Karaipirivu was the natural choice for this expansion and in time they became an autonomous force vested with the duties of protecting the Chola territorial waters, home ports, patrol of newly captured ports and coastal cities.

Privateers

The state's dependence on overseas trade for much valued foreign exchange created powerful trade-guilds, some of which grew more powerful than the regional governors.[36] With the Naval fleet often deployed in military expeditions, the guilds employed privateer navies for protection and support. These forces performed path-finding, escort and protection duties but were often also summoned to serve the Empire's interests. Like their European counterparts, the guild navies had no National markings and employed multi-national crews.

Notable Trade guilds which employed a privateer navy were:

- Nanadesa Tisaiyayirattu Ainnutruvar – literally, "the five hundred from the four countries and the thousand directions"

- Maalainattu Thiribuvana Vaanibar kzhulumam – The merchants from the high-country in three worlds (meaning the 3 domiciles of Chinese, Indian and Arabian empires)

- Maadathu valaingair (or valainzhr) vaanibar Kzhu – The pearl exporters guild from Kanchipuram

Vessels and weapons

Even before the accounts of the 1st century BCE, there were written accounts of shipbuilding and war-craft at sea, including a comprehensive book of naval-architecture in India dating to the 2nd century BCE, if not earlier.[39]:642–648

The designs of early-Chola vessels were based on trade vessels with little more than boarding implements. In time, the navy evolved into a specialized force with ships designed for specific combat roles. During the reign of Raja Raja and his son, there were a complex classification of class of vessels and its utility. Some of the survived classes' name and utility are below.[40]

| Dharani | Primary weapons platform with extensive endurance (up to 3 months) in the high-seas, they normally engaged in groups and avoided one on one encounters. Probably equivalent to modern-day Destroyers. |

| Loola | Lightly armored fast attack vessels, designed for light combat and escort duties. They could not perform frontal assaults. Equivalent to modern-day Corvettes. |

| Vajra | Highly capable fast attack crafts, with light armor, typically used to reinforce/rescue a stranded fleet. Probably equivalent to modern-day Frigates. |

| Thirisadai | The heaviest class known, comparable to modern-era Battle cruisers or Battleships. Large and heavily armoured, these ships had extensive war-fighting capabilities and endurance,[41] with a dedicated marine force of around 400 Marines to board enemy vessels. They are reported to be able to engage three vessels of Dharani class, hence the name Thirisadai, which means, three braids (Braid was also the name for oil-fire during that period).

Though all ships of the time employed a small Marine force for boarding enemy vessels, Thirisadais had separate cabins and training area for them.[42] |

.jpg.webp)

In addition to the major warship types, many ship classes and their operations in both inland waters and the open oceans are described in Purananuru:

- Yanthiram – Hybrid ship employing bot sails and oars or probably Paddle wheels of some type (Yanthiram is translated literally as 'mechanical wheel' or 'apparatus')

- Kalam – Large vessels with 3 masts which can travel in any direction irrespective of winds.

- Punai – medium-sized vessels that can be used to coastal shipping as well as inland.

- Patri – Large barge type vessel used to ferrying trade goods.

- Oodam – Small boat with large oars.

- Ambi – Medium-sized boat with a single mast and oars.

- Toni – small boat used in rocky terrain.

Apart from class definitions, there are names of Royal Yachts and their architecture. Some of which are,

- Akramandham – A royal Yacht with the Royal quarters in the stern.

- Neelamandham – A royal Yacht with extensive facilities for conducting courts and accommodation for hi-officials/ministers.

- Sarpammugam – these were smaller yachts used in the Rivers (with ornamental snake heads)

Campaigns

In the tenure spanning the 700 years of its documented existence, the Chola Navy was involved in confrontations for probably 500 years.[43] There were frequent skirmishes and many pitched battles. Not to mention long campaigns and expeditions. The 5th centuries of conflict between the Pandyas and Cholas for the control of the peninsula gave rise to many legends and folktales. Not to mention the heroes in both sides. The notable campaigns are below[44][45][46]

- War of Pandya Succession (1172)

- War of Pandya succession (1167)

- The destruction of the Bali fleet (1148)

- Sea battle of the Kalinga Campaign (1081–1083)

- The second expedition of Sri Vijaya (1031–1034)

- The first expedition of Sri Vijaya (1027–1029)

- The Annexation of Kedah (1024–1025)

- Annexation of the Kamboja (?-996)

- The invasion of Ceylon/Sri Lanka.(977-?)

- Skirmishes with Pallava Navy (903–8)

Political, cultural and economic impact

The Grand vision and imperial energy of the Father and son duo Raja Raja Chola I and Rajendra Chola I is undoubtedly the underlying reason for expansion and prosperity. But, this was accomplished by the tireless efforts and pains of the navy. In essence, Raja Raja was the first person in the sub-continent to realize the power projection capabilities of a powerful navy. He and his successors initiated a massive naval buildup and continued supporting it, and they used it more than just wars.

The Chola navy was a potent diplomatic symbol, the carrier of Chola might and prestige. It spread Hindu culture, its literary and architectural grandeur. For the sake of comparison, it was the equivalent of the " Gunboat diplomacy " of the modern-day Great powers and super powers.

There is evidence to show that the king of Kambujadesa (modern Cambodia) sent an ornamental chariot to the Chola Emperor, probably to appease him to limit his strategic attention to the Malay peninsula.

Depictions in popular culture

A number of novels and moves have been inspired by the Chola Empire and the Chola Navy, mostly in the Tamil language:

- Yavana rani : A historical novel by Sandilyan surrounding the events of the Karikala's Ascendence to throne.

- Ponniyin selvan : A novel by Kalki Krishnamurthy about the life of Rajaraja I. Considered the greatest novel written in Tamil, the novel makes significant mentions about the Chola navy and its organization.

- Kadal Pura : Historical novel by Sandilyan about the foundation of the Chalukya Chola dynasty, the conquest of Sri Vijaya, and the connections between the Chola and the Song dynasties. The novel has intricate details of the navies of the day and naval warfare, including the various weapons and tactics employed by the Cholas and Chinese navies and their combined efforts to overthrow the Sri Vijaya dynasty.

- Kanni Maadam : A historical novel by Sandilyan in the time of Rajathiraja Chola. The work describes the Pandya civil war, the geopolitical strategms between the Pandya, Ceylon, and Chola kingdoms, and detailed descriptions of battlefield maneuvering, Naval power, and logistics in an overseas campaign.

- Aayirathil Oruvan (2010 film) : A movie about the search for an exiled Chola prince directed by Selvaraghavan.

Timeline of events

The major events which had direct and some of them deep impact in the development of the Chola Naval capability are listed here, which is in no case comprehensive.

Archeological evidence: The dated excavations,

- 3000 BCE – Dugout canoes were found in Arikamedu, now in Puducherry.

- 700 BCE – The first mention of the word Yavana in pottery around korkai.(meaning Greeks or Romans).

- 300 BCE – A load-stone compass with Chinese inscriptions is found off the coast of Kaaveripoompatnam.

- 100 BCE – A settlement of Tamil/Pakrit speaking merchants founded in Rome.

- Late 1st century BCE – Roman glass was found in southern coastal regions of Tamil Nadu,[47] see: Indo-Roman trade relations

Literary references and recordings

- 356-321 BCE: The Periplus of Niarchus, an officer of Alexander the Great, describes the Persian coast. Niarchus commissioned thirty oared galleys to transport the troops of Alexander the Great from northwest India back to Mesopotamia, via the Persian Gulf and the Tigris, an established commercial route.[48]

- 334–323 BCE: Eratosthenes, the librarian at Alexandria, drew a map which includes Sri Lanka and the mouth of the Ganges. Which states the exchange of traffic and commodity in the regions.[49]

- 1st century BCE : When Vennikkuyithiar mentions about Karikala, he mentions several class of inland vessels by name. Some are Kalam, Punai, and Patri.

Gallery

An early silver coin of Uttama Chola found in Sri Lanka showing the Tiger emblem of the Cholas[1]:18[50]

An early silver coin of Uttama Chola found in Sri Lanka showing the Tiger emblem of the Cholas[1]:18[50]

The Chola empire and region of influence at the height of its power (c. 1050) during the reign of Rajendra Chola I.

The Chola empire and region of influence at the height of its power (c. 1050) during the reign of Rajendra Chola I.

References

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1955). A History of South India: From Prehistoric Times to the Fall of Vijayanagar. Oxford University Press.

- Majumdar (contains no mention of Maldives)

- Keay, John (12 April 2011), India - A History, Open Road + Grove/Atlantic, ISBN 978-0-8021-9550-0.

- Meyer, p. 73

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/when-chola-ships-of-war-anchored-on-the-east-coast/articleshow/63260602.cms

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A History of India. Berlin: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1138961159.

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1935). The CōĻas. University of Madras.

- "KING ASHOKA: His Edicts and His Times". www.cs.colostate.edu. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- "History of India by Literary Sources", Prof. E.S. Narayana Pillai, Cochin University

- Tripathi (1967), p. 457

- R, Narasimhacharya (1942). History of the Kannada Language. Asian Educational Services. p. 48. ISBN 9788120605596.

- Lindsay 2006: 101

- Shaw 2003: 426

- Halsall, Paul. "Ancient History Sourcebook: The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century". Fordham University.

- Huntingford 1980: 119.

- "South India Handbook", Robert Bradnock, pp 142.

- K.M.Panikkar, "Geographical Factors in Indian History", page 81.

- 'Mayillai.Seeni. VenkataSwamy', சங்ககால தமிழக வரலாற்றில் சில செய்திகள், page-149

- "The Commerce and Navigation of the Ancients in the Indian Ocean", William Vincent, Page 517-521

- The Archaeological Survey of India's report on Ancient ports, 1996, Pages 76–79

- Dhanalekshmi, V. (2017). "7" (PDF). Administration under the Imperial Chols 850 to 1070 AD (PhD). Manonmaniam Sundaranar University.

- "India and China- Oceanic, Educational and technological cooperation", Journal of Indian Ocean Studies 10:2 (August 2002), Pages 165–171

- Hermann Kulke, K Kesavapany, Vijay Sakhuja (2009). Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2009. pp. 92–93. ISBN 9789812309372.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Tripathi, p 465

- Tripathi, p 477

- "Antiquities of India: An Account of the History and Culture of Ancient Hindustan", Lionel D. Barnett, Page 216.

- Prakash Nanda (2003). Rediscovering Asia: Evolution of India's Look-East Policy. pp. 56–57. ISBN 81-7062-297-2.

- The Military History of south Asia, By Col. Peter Stanford, 1932.

- Military Leadership in India: Vedic Period to Indo-Pak Wars By Rajendra Nath, ISBN 81-7095-018-X, Pages: 112–119

- See Thapar, p xv

- Historical Military Heritage of the Tamils By Ca. Vē. Cuppiramaṇiyan̲, Ka.Ta. Tirunāvukkaracu, International Institute of Tamil Studies

- Shaf, William, The history of the navies of India, 1996, pp. 45–47

- Hermann Kulke, K Kesavapany, Vijay Sakhuja. Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2009. p. 92.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Indian Ocean Strategies Through the Ages, with Rare and Antique Maps", Moti Lal Bhargava, Reliance publication house, ISBN 81-85047-57-X

- "The Encyclopedia of Military History from 3500 B.C. to the Present", Page 1470-73 by Richard Ernest Dupuy, Trevor Nevitt Dupuy −1986,

- Majumdar, Romesh Chandra (1922). Corporate Life in Ancient India (PDF). Calcutta University Press.

- Maritime trade and state development in early Southeast Asia, Kenneth Hallp.34, citing Pattinapalai, a Sangam poem of the 1st century, quoted in K.V. Subrahmanya Aiyer, 'Largest provincial organisations in ancient India', Quarterly Journal of the Mythic Society 65, 1 (1954–55): 38.,

- Southeast Asia, Past and Present By D. R. Sardesai, Page 47

- Majumdar, Romesh Chandra (1954). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Classical Age. 3. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

See: The History and Culture of the Indian People

- Majumdar, Romesh Chandra (1957). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Struggle for Empire. 5. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

See: The History and Culture of the Indian People

- The History shipbuilding in the sub-continent , By Prof R C Majumdar, Pages, 521–523, 604–616

- A History of South-east Asia – Page 55 by Daniel George Edward Hall – Asia, Southeastern Publishers, 1955, Pages 465–472, 701–706

- The Politics of Plunder: The Cholas in Eleventh-Century Ceylon,George W. Spencer,The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 35, No. 3 (May, 1976), pp. 405–419, Summary at JSTOR 2053272

- "An atlas and survey of south Asian History" , By M E Sharpe, 1995, Published by Lynne Rienner, Pages 22–28

- The geo-Politics of Asia, By Michael D. Swaine & Ashley J. Tellis, Published by Konark publishers for the center for policy research, New Delhi, Page 217-219

- D The Chola Maritime Activities in Early Historical Setting, By: Dr. K.V. Hariharan

- Casson, Lionel (2012). The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Princeton University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-1400843206. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 June 2003. Retrieved 25 December 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 August 2007. Retrieved 25 December 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Chopra et al., p 31

Footnotes

- The kadaram campaign is first mentioned in Rajendra's inscriptions dating from his 14th year. The name of the Srivijaya king was Sangrama Vijayatungavarman. – K.A. Nilakanta Sastri, The CōĻas, pp 211–220

- "The Tamil merchants took glassware, camphor, sandalwood, rhinoceros horns, ivory, rose water, asafoetida, spices such as pepper, cloves, etc." – K.A. Nilakanta Sastri, A History of South India, p 173

- Kalapathy as a rank is equivalent to the modern rank of Ship Captain

- Kanni (கண்ணி) in Tamil means trap. This is not to be confused with the similarly transliterated kanni (கன்னி), which may mean any of the following in Tamil: Virgin/Unmarried Girl, First timer, the Eastern corner/direction.

- Due to the nature of their role, Kannis had a bad reputation for losses, since they could be annihilated if reinforcements were delayed by weather or unfavourable currents.

- athipathy = 'overlord' or 'Commanding Officer'

- Thalam being both the name of a tactical formation of the army and navy. Thalapathy meaning the lord of a Thalam, roughly a division, and the rank is comparable to a modern-day colonel.

- A fully equipped Chola Thalam is said to have been able to withstand an attack by a fleet more than twice its size. This is attributed to the superior range of missile weapons in the Chola inventory.

- mandalam in Tamil and other Indian languages is the word representing the number 48

- Ganam in Tamil means volume and three

- Normally, this would be the minimum strength/size of the overseas deployment.

- Only 2 instances of an Ani being deployed in a combat have been documented.

- The title varied according to where the fleet is based, and the Commander. For example, the eastern fleet commander would be named Keelpirivu-athipathy or Keelpirivu-Nayagan or Keelpirivu-Thevan, depending on the person. Keelpirivu : 'Eastern fleet'.

- The rise of Chera naval power put economic and military pressure on the Chola Empire, prompting them to permanently station a fleet in the Malabar coast.

External links

- http://www.tifr.res.in/~akr/crab_webtifr.html (Indian subcontinent section)

- https://web.archive.org/web/20080514170634/http://www.sabrizain.demon.co.uk/malaya/early2.htm

- https://web.archive.org/web/20091203133836/http://www.tsr8283.com/general/history.htm

- http://nandhivarman.indiainteracts.com/2007/11/01/chola-maritime-conquests-and-technological-grandeur/

- http://www.cmi.ac.in/gift/Archeaology/arch_tambaramhistory.htm

- http://www.sangam.org/articles/view2/print.php?uid=1012

- https://web.archive.org/web/20081105144141/http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/NAVY/History/1600s/Prakash.html

- Keay, John (12 April 2011), India: A History, Open Road + Grove/Atlantic, ISBN 978-0-8021-9550-0

- Tripati, Sila (April 2006), "Ships on Hero Stones from the West Coast of India" (PDF), International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 35 (1): 88–96, doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2005.00081.xCS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Rao, K.V. Ramakrishna (2007), "The Shipping Technology of Cholas" (PDF), 27th Annual South Indian History Congress: 326–345