Chemisorption

Chemisorption is a kind of adsorption which involves a chemical reaction between the surface and the adsorbate. New chemical bonds are generated at the adsorbant surface. Examples include macroscopic phenomena that can be very obvious, like corrosion, and subtler effects associated with heterogeneous catalysis, where the catalyst and reactants are in different phases. The strong interaction between the adsorbate and the substrate surface creates new types of electronic bonds.[1]

In contrast with chemisorption is physisorption, which leaves the chemical species of the adsorbate and surface intact. It is conventionally accepted that the energetic threshold separating the binding energy of "physisorption" from that of "chemisorption" is about 0.5 eV per adsorbed species.

Due to specificity, the nature of chemisorption can greatly differ, depending on the chemical identity and the surface structural properties. The bond between the adsorbate and adsorbent in chemisorption is either ionic or covalent.

Uses

An important example of chemisorption is in heterogeneous catalysis which involves molecules reacting with each other via the formation of chemisorbed intermediates. After the chemisorbed species combine (by forming bonds with each other) the product desorbs from the surface.

Self-assembled monolayers

Self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) are formed by chemisorbing reactive reagents with metal surfaces. A famous example involves thiols (RS-H) adsorbing onto the surface of gold. This process forms strong Au-SR bonds and releases H2. The densely packed SR groups protect the surface.

Gas-surface chemisorption

Adsorption kinetics

As an instance of adsorption, chemisorption follows the adsorption process. The first stage is for the adsorbate particle to come into contact with the surface. The particle needs to be trapped onto the surface by not possessing enough energy to leave the gas-surface potential well. If it elastically collides with the surface, then it would return to the bulk gas. If it loses enough momentum through an inelastic collision, then it "sticks" onto the surface, forming a precursor state bonded to the surface by weak forces, similar to physisorption. The particle diffuses on the surface until it finds a deep chemisorption potential well. Then it reacts with the surface or simply desorbs after enough energy and time.[2]

The reaction with the surface is dependent on the chemical species involved. Applying the Gibbs energy equation for reactions:

General thermodynamics states that for spontaneous reactions at constant temperature and pressure, the change in free energy should be negative. Since a free particle is restrained to a surface, and unless the surface atom is highly mobile, entropy is lowered. This means that the enthalpy term must be negative, implying an exothermic reaction.[3]

Physisorption is given as a Lennard-Jones potential and chemisorption is given as a Morse potential. There exists a point of crossover between the physisorption and chemisorption, meaning a point of transfer. It can occur above or below the zero-energy line (with a difference in the Morse potential, a), representing an activation energy requirement or lack of. Most simple gases on clean metal surfaces lack the activation energy requirement.

Modeling

For experimental setups of chemisorption, the amount of adsorption of a particular system is quantified by a sticking probability value.[3]

However, chemisorption is very difficult to theorize. A multidimensional potential energy surface (PES) derived from effective medium theory is used to describe the effect of the surface on absorption, but only certain parts of it are used depending on what is to be studied. A simple example of a PES, which takes the total of the energy as a function of location:

where is the energy eigenvalue of the Schrödinger equation for the electronic degrees of freedom and is the ion interactions. This expression is without translational energy, rotational energy, vibrational excitations, and other such considerations.[4]

There exist several models to describe surface reactions: the Langmuir–Hinshelwood mechanism in which both reacting species are adsorbed, and the Eley–Rideal mechanism in which one is adsorbed and the other reacts with it.[3]

Real systems have many irregularities, making theoretical calculations more difficult:[5]

- Solid surfaces are not necessarily at equilibrium.

- They may be perturbed and irregular, defects and such.

- Distribution of adsorption energies and odd adsorption sites.

- Bonds formed between the adsorbates.

Compared to physisorption where adsorbates are simply sitting on the surface, the adsorbates can change the surface, along with its structure. The structure can go through relaxation, where the first few layers change interplanar distances without changing the surface structure, or reconstruction where the surface structure is changed.[5] A direct transition from physisorption to chemisorption has been observed by attaching a CO molecule to the tip of an atomic force microscope and measuring its interaction with a single iron atom.[6]

For example, oxygen can form very strong bonds (~4 eV) with metals, such as Cu(110). This comes with the breaking apart of surface bonds in forming surface-adsorbate bonds. A large restructuring occurs by missing row.

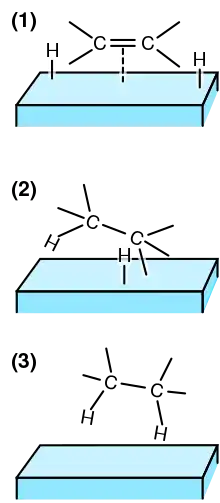

Dissociation chemisorption

A particular brand of gas-surface chemisorption is the dissociation of diatomic gas molecules, such as hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen. One model used to describe the process is precursor-mediation. The absorbed molecule is adsorbed onto a surface into a precursor state. The molecule then diffuses across the surface to the chemisorption sites. They break the molecular bond in favor of new bonds to the surface. The energy to overcome the activation potential of dissociation usually comes from the translational energy and vibrational energy.[2]

An example is the hydrogen and copper system, one that has been studied many times over. It has a large activation energy of .35 – .85 eV. The vibrational excitation of the hydrogen molecule promotes dissociation on low index surfaces of copper.[2]

See also

References

- Oura, K.; Lifshits, V.G.; Saranin, A.A.; Zotov, A.V.; Katayama, M. (2003). Surface Science, An Introduction. Springer. ISBN 3-540-00545-5.

- Rettner, C.T; Auerbach, D.J. (1996). "Chemical Dynamics at the Gas-Surface Interface". Journal of Physical Chemistry. 100 (31): 13021–33. doi:10.1021/jp9536007.

- Gasser, R.P.H. (1985). An introduction to chemisorption and catalysis by metals. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198551630.

- Norskov, J.K. (1990). "Chemisorption on metal surfaces". Reports on Progress in Physics. 53 (10): 1253–95. Bibcode:1990RPPh...53.1253N. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/53/10/001.

- Clark, A. (1974). The Chemisorptive Bond: Basic Concepts. Academic Press. ISBN 0121754405.

- Huber, F.; et al. (12 September 2019). "Chemical bond formation showing a transition from physisorption to chemisorption". Science. 365 (xx): 235–238. Bibcode:2019Sci...366..235H. doi:10.1126/science.aay3444. PMID 31515246. S2CID 202569091.

Bibliography

- Tompkins, F.C. (1978). Chemisorption of gases on metals. Academic Press. ISBN 0126946507.

- Schlapbach, L.; Züttel, A. (15 November 2001). "Hydrogen-storage materials for mobile applications" (PDF). Nature. 414 (6861): 353–8. doi:10.1038/35104634. PMID 11713542. S2CID 3025203.