Charles Paul de Kock

Charles Paul de Kock (May 21, 1793 in Passy, Paris – April 27, 1871 in Paris) was a French novelist.

.png.webp)

Biography

His father, Jean Conrad de Kock, a banker of Dutch extraction, victim of the Terror, was guillotined in Paris 24 March 1794. His mother, Anne-Marie Perret, née Kirsberger, was a widow from Basel. Paul de Kock began life as a banker's clerk. For the most part he resided on the Boulevard St. Martin.

He began to write for the stage very early, and composed many operatic libretti. His first novel, L'Enfant de ma femme (1811), was published at his own expense. In 1820 he began his long and successful series of novels dealing with Parisian life with Georgette, ou la Nièce du tabellion. He was most prolific and successful during the Restoration and the early days of Louis Philippe.

| French literature |

|---|

| by category |

| French literary history |

| French writers |

|

| Portals |

|

He was relatively less popular in France itself than abroad, where he was considered as the special painter of life in Paris. Dostoevsky, in his novel Poor Folk (1846), wrote that reading a novel by De Kock was not becoming for ladies<Poor Folk, Everyman's Library 1948 p. 63>. James Joyce's Ulysses includes references to Paul De Kock, including innuendos on his name in the Calypso, Sirens and Circe episodes. His novel The Girl with the Three Pairs of Stays is also mentioned in the Circe episode. Major Pendennis' remark (in the novel "Pendennis" by the English author William Makepeace Thackeray) that he had read nothing of the novel kind for thirty years except Paul de Kock, who certainly made him laugh, is likely to remain one of the most durable of his testimonials, and may be classed with the legendary question of a foreign sovereign to a Frenchman who was paying his respects, Vous venez de Paris et vous devez savoir des nouvelles. Comment se porte Paul de Kock? The 1920 Encyclopedia Americana attributes his greater popularity abroad to his style, which it describes as his worst feature . . . barely presentable, a fault evidently due to deficiency of education. . . . the defects of style disappear in translation.[1]

The disappearance of the grisette and of the cheap dissipation described by Henri Murger practically made Paul de Kock obsolete. But to the student of manners his portraiture of low and middle class life in the first half of the 19th century at Paris still has its value.

Works

Paul de Kock wrote about 100 volumes. With the exception of a few excursions into historical romance and some miscellaneous works of which his share in La Grande yule, Paris (1842), is the chief, they are all stories of middle-class Parisian life, of guinguettes and cabarets and equivocal adventures of one sort or another. The most famous are André le Savoyard (1825) and Le Barbier de Paris (1826).

The stories are full of observation at first hand and of spicy humor. The 1905 New International Encyclopædia describes his stories as rather vulgar, but not immoral, demanding no literary training and gratifying no delicate taste. They were extraordinarily popular. In 1905, Paul de Kock was seldom mentioned in the more conventional French histories of French literature. Typical examples of his work are:[2]

- Gustave le mauvais sujet (1821)

- Frère Jacques (1822)

- La laitière de Montfermeil (1827)

- Monsieur Dupont (1825)

- Un Tourlouron (1837)

- La femme, le mari et l'amant (1829)

- Le cocu (1831)

- La pucelle de Belleville (1834)

A 56-volume edition of his works came out in 1884. He has had imitators, among them his son Henri (1819–92).[2]

Further reading

- Paul de Kock, Mémoires (1873)

- Th. Trimm, La vie de Charles Paul de Kock (Paris, 1873)

Notes

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Kock, Charles Paul de". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Kock, Charles Paul de". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

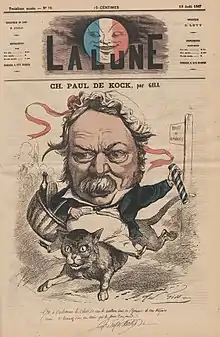

- 1867 Caricature of Charles Paul de Kock by André Gill

- Works by Paul de Kock at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Charles Paul de Kock at Internet Archive

- Works by Charles Paul de Kock at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Guardian Angel A short excerpt from Zizine (1837) at Ex-classics.