Charles Goeller

Charles Goeller (1901–1955) was an American artist best known for precise and detailed paintings and drawings in which, he once said, he aimed to achieve "emotion expressed by precision."[1][note 1] Employing, as one critic wrote, an "exquisitely meticulous realism,"[2] he might take a full year to complete work on a single picture.[1] Early in his career he achieved critical recognition for his still lifes, in which one critic saw an "acumen of genius" working to produce "truly superb achievement of team work between eyes that see and hands that do."[3] Later, he also became known for cityscapes in which he employed precisionist flat planes and geometric forms to show the physical structures of his subjects.[1][4]

Charles Goeller | |

|---|---|

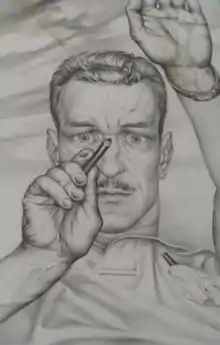

Charles Goeller, self portrait, "How Does It Feel to be a Piece of Paper?" (crayon on paper, 15" x 12") | |

| Born | Charles Louis Goeller November 10, 1901 |

| Died | March 6, 1955 (aged 53) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Artist, art teacher |

Art training

Goeller's father and grandfather were structural engineers who ran a successful iron and steel fabricating plant in Newark, New Jersey.[5] Upon graduating from high school Goeller studied mathematics, civil engineering, and architecture first at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and later at Cornell University.[1][6] Afterwards his grandfather agreed to support five years of art and architecture study in France. Beginning in 1923 he received art instruction from Jean Despujols and other members of the faculty at the École Américaine de Fontainebleau.[1][4] During this period Goeller also studied at Académie de la Grande Chaumière, a small left-bank atelier in Paris.[1][7]

Art career, 1930s

After his return to the United States Goeller joined the young American artists associated with the Daniel Gallery located on Madison Avenue in New York. In March 1929 the gallery included his work in an exhibition that also included paintings by Peter Blume, Preston Dickinson, Elsie Driggs, Karl Knaths, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi.[8][note 2] Reviewing the show, critics called attention to a still life of his called "Checkered Tablecloth." One remarked on the high quality of the work and pointed out that the cloth "drapes itself cunningly,"[13] another noted his "meticulous technique" and "vibrating color,"[14] and a third saw in it a tendency toward Neues Sachlichkeit.[2][note 3][note 4]

The following year the same still life appeared in a group exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art. Called "Forty-six Painters and Sculptors Under Thirty-One Years of Age," it contained an international mix of art by younger artists, including many whose careers would later flourish.[note 5] One critic for the New York Times, Elisabeth Luther Cary, praised the painting as "a truly superb achievement of team work between eyes that see and hands that do"[3] and another Times critic, Edward Alden Jewell, said his still life, with its "fabric wizardry," was attracting much attention.[17] The same year Jewell commented on "Blue Brocade," a still life of Goeller's included in a group show at the Daniel Gallery. Calling it "sumptuous" and "ravishing," he said its virtuosity made it comparable to the work of early-Renaissance goldsmiths and concluded: "Here, once more, in this expert solution of a painter's problem, the centuries become but as a day."[17]

In a paper read at the College Art Association meeting in 1931 Alfred H. Barr cited Goeller as one of a group of young Americans whom he called "New Objectivists."[18][note 6][note 7][note 8] A year later Goeller exhibited work in a show called "American Scenes and Subjects" put on by the College Art Association at the Rehn Gallery.[20][note 9] Reviewing a group exhibition at the Daniel Gallery in 1931, a critic referred to Goeller and the show's other artists as practitioners of "pure painting." By this he meant the group focused the experience of the observer. He said the artists aimed to draw the viewer's attention to "what lies beyond or beneath or above."[23] Another reviewer of that show said one of Goeller's paintings in the exhibition was "a good illustration of the modern use of color as an integral part of the expression form."[24] In 1933 Goeller showed still lifes, figure studies, and landscapes in a solo exhibition at Argent Gallery. In reviewing the show, Howard Devree of the New York Times said Goeller had made a "very commendable achievement." He praised the still lifes for his outstanding use of color and the remarkable fabric textures he was able to achieve, but felt the figure studies were not maturely realized and the landscapes overly flat.[25][note 10]

Having achieved critical recognition for his still lifes in the early 1930s, Goeller painted a larger number of landscapes during the middle and late years of the decade.[4][25] After joining the Public Works of Art Project, he painted the highly regarded "Third Avenue" in 1934.[29] In a style that was identified as precisionist, this painting used geometric forms and flat planes to emphasize "the scale and power of modern technology," according to a biographer,[4] Following his employment in the Public Works of Art Project, Goeller joined the Federal Art Project.[30] Subsequently, a mural of his won a cash prize in a 1935 competition and was exhibited at the Architectural League.[31]

Art career, 1940s–1950s

During the 1940s Goeller was represented by the Bonestell Gallery.[note 11] In reviewing the first of his shows with that gallery Howard Devree noted a wide range in style, "from almost stereoscopic realism to a misty impression of New Jersey meadows and veritable silver point drawings of great delicacy and technical perfection."[32] In reviewing the second he added that Goeller found "reluctant beauty" in the landscapes and was able to obtain a "strange mood."[33]

Sometime before 1943 Goeller drew a trompe l'oeil self-portrait entitled "How Does It Feel to be a Piece of Paper?" The drawing makes it seem as if the viewer's eye is the paper on which the artist's pencil is descending.[1] He showed it in the Society of Independent Artists annual exhibition of 1943, at the Bonestell Gallery in 1945, and in museum exhibitions in 1943, 1949, and 1953.[1][note 12] In 1941 and 1942 he showed with a group called Modern Artists of New Jersey.[37][38][note 13] In 1943 Goeller joined the Associated Artists of New Jersey and showed with them at the Riverside Museum in 1943, 1944, 1947, and 1950.[41][42][43][44][note 14]

In 1952, not long before his untimely death, a landscape of Goeller's appeared in the Whitney Museum annual exhibition of contemporary painting. In reviewing the show Howard Devree listed it along with others that he deemed to be outstanding, describing it as a "moody monochromatic interpretation of the Jersey meadows."[48]

At the outset of his artistic career Goeller said he aimed to achieve coherence in his work and a freedom from exaggeration. He said he wished to avoid "sacrifices to obtain an effect."[note 15] At the end of his career his work was noted as evoking a pervasive mood of "wistful loneliness" and possessing a "haunting, disquieting aspect" which bore out his belief in "emotion expressed by precision."[1]

Art teacher

Goeller, who has been called a "passionate advocate for art education,"[4] was an art instructor in the College of Architecture at Cornell University between 1931 and 1933[49][50] and an instructor in the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Arts in the early 1950s.[51][52]

Personal life

Goeller was born in Irvington, New Jersey, on November 10, 1901.[53][54] His father, Charles Goeller was born 1876 in Germany and brought to the United States by his parents in 1879.[55][56][57] Apart from the few years in Irvington between 1900 and 1910, he lived most of his life in Newark. He was living in nearby Elizabeth when he died in 1961, having outlived his son Charles by six years. In 1884 Goeller's paternal grandfather, Frederick Goeller, founded the Goeller Iron Works in Newark, specializing in ornamental structures.[5][56] By 1917 Goeller's father had assumed control of the business and renamed it the Charles Goeller Steel Co.[58] In 1942, he again reorganized it, this time as Charles Goeller, Inc., contractors in structural iron and steel.[59] Goeller's mother was Hulda Weiss Goeller, born in 1878, who emigrated to the United States with her parents and seven siblings in 1883.[60] He had an older brother, Leopold, born in Newark in 1899, and a younger sister, Hulda, born in Newark in 1907.[56][61][62]

Goeller lived at his parents' Newark home through the 1920s,[54][63] he shared an apartment in New York in the 1930s,[1] and returned to his parents' home in the early 1940s.[64] He lived in and around northern New Jersey during the remainder of his life.[65]

He moved from New York to New Jersey in 1939 to work in his father's iron and steel factory.[1][64] During World War II he was employed in the graphic art department of Fleetwings, a firm that made airplanes and aircraft components, located in Bristol, Pennsylvania.[1] In addition to preparing technical drawings Goeller wrote a cartoon for the firm's bi-weekly tabloid newspaper, Fleetwing News. The cartoon featured a female character, Evangeline, who represented the contributions that young women were making to homefront production work.[1][note 16] Goeller's wartime contribution also included evening classes he taught at Drexel Institute to help prepare for young people for factory work.[1] He died at his home in Elizabeth, New Jersey, on March 6, 1955.[65]

Other names

Goeller's full name was Charles Louis Goeller.[70] He signed his works either Goeller or Charles L. Goeller.[4]

Notes

- Goeller made the statement to an interviewer in 1953. The quote appeared in an article in the Newark Sunday News of June 28, 1953. The article is cited in a critical essay within an art exhibition catalog, Emotion Expressed Through Precision: The Art of Charles Goeller (New York, N.Y.: Gallery, 2003). The essay was by Gail Stavitsky. The exhibition was held at three New York galleries: Gallery, Franklin Riehlman Fine Art, and Megan Moynihan Fine Art. Gallery is the name of a gallery, now called Gallery Schlesinger, on 24 East 73rd Street, Manhattan.

- The Daniel Gallery had opened in 1913. Run by Charles Daniel, with help from Alanson Hartpence, it showed the work of young American artists such as Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Rockwell Kent, Maurice Prendergast, and Man Ray.[9][10][11] One of the relatively few galleries that showed art by women, it had a stable of artists that included many of Katherine Schmidt's friends from the Art Students League and Whitney Studio Club.[9][10][11][12]

- The still life was first shown in 1928 at the Société du Salon d'Automne, Paris. Subsequent to the Daniel Gallery show it appeared in 1930 at the Museum of Modern Art ("46 Painters and Sculptors Under 35 Years of Age") and in Goeller's one-man show at the Argent Gallery.[1]

- The term Neues Sachlichkeit is said to be difficult to define. It seems generally agreed that the style evolved as an extension to Expressionism, that aimed to achieve a "magic naturalism" through a precise matter-of-factness.[15] Magic naturalism, also called magic realism, has been defined as post-expressionist style that, in opposition to abstraction and emotionally charged imagery, was characterized by ultrasharp focus in depicting "the autonomy of the objective world" and "the wonder of matter" in such a way that objects would be "seen anew." The quoted text appears in Lois Parkinson Zamora and Wendy B. Faris, eds., Magical Realism: Theory, History, Community (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1995)

- In addition to Goeller, the American artists in this show included Peggy Bacon, Peter Blume, Alexander Brook, Elsie Driggs, Arshile Gorky, Stefan Hirsch, Luigi Lucioni, Reginald Marsh, Marjorie Phillips, and Ben Shahn.[16]

- The others mentioned by Barr were Reginald Marsh, Charles Burchfield, Peter Blume, Stefan Hirsch, Luigi Lucioni and Katherine Schmidt.[18]

- Founded in 1911, the College Art Association aimed to establish art and art history as subjects for academic study. It has accomplished this objective through conferences, standards-setting, sponsored exhibitions, and the publication of influential journals, including Art Bulletin, Parnassus, and Art Journal.[19]

- The term New Objectivity was a common translation of Neues Sachlichkeit.

- Frank Knox Morton Rehn (1886-1956), son of the artist Frank Knox Morton Rehn (1848-1914), founded the gallery in 1918. Although its official name was the Frank K. M. Rehn Galleries, it was often called the Rehn Gallery or simply Rehn's. Goeller was not represented by the gallery and apparently only showed there on this one occasion.[21][22]

- The Argent Galleries were located in the headquarters building of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors on West 57th Street. Founded in 1930, they were mainly used to show work by the group's members, but, in between these shows, they were made available for outsiders' use, particularly one-man exhibitions such as Goeller's.[26][27][28]

- Goeller was given solo exhibitions at the Bonestell Gallery in 1945 and 1947.[32][33] The Bonestell Gallery, operated by Blanche Bonestell at 18 East 57th Street, showed modern painting and sculpture by a wide variety of artists, including especially American women, Hispanics, and, in general, avant-garde artists of the 1940s and 1950s.[34][35] In 1939 the gallery held an exhibition of a group of experimental artists known as "The Ten" whose members were Ben-Zion, Ilya Bolotowsky, Adolph Gottlieb, Louis Harris, Jack Kufeld, Mark Rothko (then known as Marcus Rothkowitz ), Louis Schanker, and Joseph Solman.[36]

- In 1943 Goeller showed the self portrait at the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco; in 1949 at the Irvington Art and Museum Association, New Jersey; and in 1953 at the New Jersey State Museum, Trenton.[1]

- The Modern Artists of New Jersey group was headed by Raymond O'Neill, an artist who taught art at Columbia University during the 1930s, and who was chairman of the New Jersey State Art Committee in 1939. The group staged exhibitions of work by New Jersey artists, particularly young, unknown artists, and sponsored lectures, demonstrations, and public forums to further the advancement of modern art.[39][40]

- The Associated Artists of New Jersey was founded in 1941 in the studio of artist Anne Steele Marsh, sister-in-law of artist Reginald Marsh. Limited to a membership of fifty, the group staged exhibitions in galleries and museums and sponsored public forums.[45][46][47]

- Goeller's statement appears in an undated clipping (ca. 1827–28) quoted by Gail Stavitsky in the art exhibition catalog of 2003, already cited.[1]

- Fleetwings did not win government contracts to build complete warplanes but did become a successful supplier of wings, control surfaces, and other components, such as solenoid-operated flap valves.[66] It also made specialized tools, including a "light-weight long-reach jaw for rivet squeezers, enabling women to take over what had been strictly a man's job."[67][68] In 1943 the firm ran two ten-hour shifts with a total of close to 5,000 employees.[1][69]

References

- Gail Stavitsky; Charles Goeller (2003). [Art Exhibition Catalog] Emotion Expressed Through Precision. New York: Gallery. pp. 32 [unpaginated].

- Margaret Breuning (1929-03-09). "Many Group Exhibitions of Water Colors and Prints Feature the Week". New York Evening Post.

Charles Goeller's "Checkered Table Cloth" makes a handsome painting in which shapes and colors and lines all get accounted for in plastic design. There is something of "Neues Sachlichkeit" in this exquisitely meticulous realism, a fact which shows how art currents are setting.

- Elizabeth Luther Cary (1930-04-13). "THE LEXICON OF YOUTH: A Stimulating Mixed Exhibition Is Now Presented at the Museum of Modern Art". New York Times. p. 132.

Charles Goeller in his still life gives due weight to a heavy table, textile quality to a white towel with red-lined border, and the acumen of genius to the discriminated planes and color regulations of a checked tablecloth. A truly superb achievement of team work between eyes that see and hands that do.

- "Charles L. Goeller". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- "Charles Goeller". New York Times. 1961-08-01. p. 31.

- Cornell University (1919). The Register, Cornell University. p. 257.

- "Home - L'Académie de la Grande Chaumière". Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- "Display ad: Daniel Gallery; Special Exhibition". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1929-03-03. p. E7.

Blume, Dickinson, Driggs, Goeller, Knaths, Kuniyoshi; 600 Madison Ave.

- "Oral history interview with Katherine Schmidt, 1969 December 8–15". Oral Histories; Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- "Man With a New Method". New York Press. 1914-01-25. p. 8.

- Robert M. Austin (11 December 1992). American Salons : Encounters with European Modernism, 1885–1917. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-19-536220-6.

- Michael Kimmelman (1994-01-07). "Review/Art; An Early Champion of Modernists". New York Times. p. C27.

The list of artists, diverse and impressive, includes Man Ray and Alexander Archipenko, Joseph Stella and Marsden Hartley, Charles Demuth and Charles Sheeler, Peter Blume and Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Marguerite Zorach and William Zorach, Raphael Soyer and Glenn O. Coleman.

- Edward Alden Jewell (1929-03-10). "BEAUTIFUL FRENCH WORK: Water-Colors and Drawings Yield No Dull Moment--Coleman and Other Artists". New York Times. p. 136.

Charles Goeller is another new man, whose name ought to become familiar enough if he continues to paint as well as he has painted in "The Checkered Tablecloth." The fabric, humble but brightly blue and white, drapes itself cunningly.

- "Daniel Gallery Opens With American Group". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1929-11-03. p. E7.

- Dennis Crockett (1999). German Post-Expressionism : The Art of the Great Disorder 1918Ð1924. Penn State Press. p. 156. ISBN 0-271-04316-4.

- "MODERN ART MUSEUM OPENS 'UNDER 35' SHOW: Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture Intended to Show Vitality of Younger Artists". New York Times. 1930-04-13. p. 33.

- Edward Alden Jewell (1929-04-20). "BEAUTY STILL ORACULAR: Birthday Armor at Metropolitan--Young Moderns--Edzard Wins His Battle--Cats". New York Times. p. 108.

.. and here is another piece of fabric wizardry by Charles Goeller, whose table with its blue and white checked cloth at the Museum of Modern Art has been attracting so much attention. The present fabric is more sumptuous; it is a ravishing blue brocade, rumpled, of course, to accommodate virtuosity that would look far before finding a rival—the kind of virtuosity one associates with the goldsmiths of the early Renaissance. Here, once more, in this expert solution of a painter's problem, the centuries become but as a day.

- Alfred H. Barr (May 1931). "Postwar Painting in Europe; Paper read at the Twentieth Annual Meeting of the College Art Association". Parnassus (PDF). New York: Stanley Lewis. 3 (5): 20–22. JSTOR 770532.

In America, if one may diverge geographically for a moment, the New Objectivity has spread with amazing speed, in large part because the formal, abstract qualities of much fashionable French painting are essentially foreign to American art, which is naturally more naive and more realistic. Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, Charles Sheeler, Preston Dickinson, who once experimented with Cezannesque or cubistic formulae, have become of recent years only slightly stylized realists, while Edward Hopper definitely continues the tradition of Homer. Reginald Marsh, Charles Burchfield, Charles Goeller, Peter Blume, Stefan Hirsch, Luigi Lucioni and Katherine Schmidt are some of the younger Americans who might be classed as New Objectivists.

- "Centennial | College Art Association | CAA | Advancing the history, interpretation, and practice of the visual arts for over a century". College Art Association. New York. Archived from the original on 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- Edward Alden Jewell (1931-09-29). "ART: Three New Exhibitions. Art From the Andes. Americans' Work Shown. Burr's Etchings on View". New York Times. p. 23.

- "Detailed description of the Frank K.M. Rehn Galleries records, 1858-1969, bulk 1919-1968 - Digitized Collection". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-05-21.

- "Frank K. M. Rehn Galleries". Burchfield Penney Art Center. Retrieved 2016-05-21.

- Edward Alden Jewell (1931-11-04). "ART: Exhibition at Daniel Gallery". New York Times. p. 29.

- Margaret Breuning (1931-11-07). "Retrospective Exhibition of Works by Henri Matisse at Modern Museum". New York Evening Post. p. D7.

Charles Goeller's "Blue Box" is almost virtuosity, yet sheers well away from that dangerous reef. It is a good illustration of the modern use of color as an integral part of the expression form.

- Howard Devree (1933-11-26). "Argent Gallery". New York Times. p. X12.

The still-lifes are outstanding both in color and in the remarkable fabric textures obtained. Figure studies among the paintings seem not so maturely realized; and landscapes are more flatly mural in "feel" than his other work. But the carefully distinguished textures in the still-life subjects make Mr. Goeller's first one-man show a very commendable achievement.

- "Women Artists in New Quarters; Hold Opening Exhibition in Recently Acquired Argent Galleries". New York Sun. 1930-05-07. p. 20.

- Marion Clyde McCarroll (1930-05-12). "Women and Artists May Be Traditionally Impractical, But Here's a Combination of the Two Things That Isn't; Argent Galleries Are Tangible Proof of Their Ability". New York Evening Post. p. 5.

- "A Descriptive Calendar of the New York Galleries". Parnassus (PDF). New York: Stanley Lewis. 6 (5): 26–33. March 1934. JSTOR 770969.

Five shows are held yearly, including two new membership Jury Shows. The balance of the season is filled with one-man shows by both men and women.

- "Third Avenue by Charles L. Goeller". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- "Detailed description of the Federal Art Project, Photographic Division collection, circa 1920-1965, bulk 1935-1942 | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution". Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Philippa Whiting (February 1935). "Speaking About Art". American Magazine of Art (PDF). 28 (2): 108. JSTOR 23932788.

- Howard Devree (1945-10-07). "A DOZEN ONE-MAN SHOWS: Genre and Abstraction Surrealism to Dogs". New York Times. p. X7.

Charles Goeller, at the Bonestell, ranges from almost stereoscopic realism to a misty impression of the New Jersey meadows and veritable silver point drawings of great delicacy and technical perfection. This dozen small pictures, imaginative and well realized, constitutes some of the artist's most persuasive work. The large desktop still-life, "Dream of Fair Women," is an ambitious undertaking spiritedly carried out.

- Howard Devree (1947-05-04). "Exhibitions by Four Sculptors -- Painting From Traditional to Ultra-Modern". New York Times. p. X10.

Charles L. Goeller, at the Bonestell Gallery, continues to find reluctant beauty in the Jersey meadows. Goeller's work is individual—most of all when with stereoscopic foreground and misty of flatly brushed background he obtains strange mood. Sparingly used intense color heightens his effects.

- "Display Ad: Blanche Bonesteil Gallery". Partisan Review (PDF). New York. 15 (1): 124. January 1948. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- "Display Ad: Shum From Spain; Paintings". New York Times. 1946-11-10. p. X11.

- "The Ten". Warholstars, a site by Gary Comenas dedicated to the memory of the art writer and collector, William S. Wilson. Archived from the original on 2016-05-21. Retrieved 2016-05-30.

- Howard Devree (1941-11-16). "Brief Comment on Some Shows Recently Opened". New York Times. p. X10.

- "Along the Trail". New York Times. 1942-04-26. p. X5.

- "CAFE VENUS RULING CITED IN ART ROW: Modern Artists Group in Jersey Hails Burnett as Better Critic Than Montclair Museum". New York Times. 1936-03-24. p. 2.

- New Jersey: A Guide to Its Present and Past. Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration for the State of New Jersey. 1939. p. 186.

- Howard Devree (1943-05-16). "A REVIEWER'S NOTEBOOK: Brief Comment on Some Recently Opened Group and One-Man Shows". New York Times. p. X12.

- Howard Devree (1944-11-12). "A REVIEWER'S NOTES: Brief Comment on Some Recently Opened Group and One-Man Exhibitions". New York Times. p. X8.

- Edward Alden Jewell (1947-03-04). "IRISH ART DISPLAY OPENS AT GALLERY: Exhibition of Work by Painters in Ireland Is Presented by Associated Artists Group". New York Times. p. 29.

- "FOURTH SHOW HERE BY JERSEY ARTISTS: 85 Works Included in Display of Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture at Riverside". New York Times. 1950-02-11. p. 8.

- "Essex Fells, N.J.". New York Times. 1941-07-20. p. X7.

- "N. J. Artists to Exhibit in Chatham". The Forum. Hackettstown, N.J. 1977-02-23. p. 25.

- Vivien Raynor (1990-05-27). "ART; Eclectic Works at an Old Mill". New York Times. p. 20.

- Howard Devree (1952-11-09). "BALANCED ANNUAL: Contemporary Painting at the Whitney". New York Times. p. X9.

- "Faculty" (PDF). Announcement of the College of Architecture for 1931-32; Architecture, Landscape Architecture, Painting, Sculpture (PDF). Ithaca, New York: Cornell University. 22 (9): 3. 1930-12-15. Retrieved 2016-05-15.

- "Faculty" (PDF). Announcement of the College of Architecture for 1932-33; Architecture, Landscape Architecture, Painting, Sculpture (PDF). Ithaca, New York: Cornell University. 23 (9): 3. 1931-12-12. Retrieved 2016-05-15.

- David B. Dearinger. "Leo Dee (1931–2004)". Traditional Fine Arts Organization. Archived from the original on 2015-12-04. Retrieved 2015-10-02.

[This] essay was excerpted from the illustrated catalogue (ISBN 0-934552-72-X) for the exhibition Power Line: The Art of Leo Dee, held February 18 through April 30, 2005 at the Boston Athenæum.

- John R. Mayor (December 1951). "What Is Going on in Your School?". Mathematics Teacher (PDF). 44 (8): 583. JSTOR 27953895.

- "Charles L Goeller in entry for Charles Goeller, 1915". "New Jersey State Census, 1915", database, FamilySearch. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- "Charles Goeller, 1925". "New York, New York Passenger and Crew Lists, 1909, 1925-1957," database with images, FamilySearch; citing Immigration, New York, New York, United States, NARA microfilm publication T715 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.). Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- "Karl Friedrich Goeller". "Deutschland Geburten und Taufen, 1558-1898," database, FamilySearch; citing Speyer, Bayern, Germany; FHL microfilm 192,373. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- "Leopold F Goeller in household of Charles Goeller, District 2 Irvington town, Essex, New Jersey, United States". "United States Census, 1900," database with images, FamilySearch; citing sheet 7B, family 149, NARA microfilm publication T623 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,240,969. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- "Hulda Louise Goeller, 1925". ""United States Passport Applications, 1795-1925," database with images, FamilySearch; citing Passport Application, New Jersey, United States, source certificate #508962, Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 - March 31, 1925, 2700, NARA microfilm publications M1490 and M1372 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,763,401. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- "Charles Goeller, 1917-1918". "United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918," database with images, FamilySearch; citing Newark City no 9, New Jersey, United States, NARA microfilm publication M1509 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,753,733. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- "CHARLES GOELLER INC - ROSELLE PARK, NJ - Business Page". Dun & Bradstreet, Inc. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- "Johanna Weiss, 1883". "New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1891," database with images, FamilySearch; citing NARA microfilm publication M237 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- "Leopold F. Goeller, 24 Jul 1899". "New Jersey, Births, 1670-1980," database, FamilySearch; citing Newark, Essex, New Jersey, United States, Division of Archives and Record Management, New Jersey Department of State, Trenton.; FHL microfilm 494,243. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- "Hulda Goeller, 1925". "New York, New York Passenger and Crew Lists, 1909, 1925-1957," database with images, FamilySearch; citing Immigration, New York, New York, United States, NARA microfilm publication T715 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.). Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- "Charles L Goeller in entry for Charles Goeller, 1930". "United States Census, 1930", database with images, FamilySearch. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- "Charles L Goeller in household of Charles Goeller, Maplewood Township, Essex, New Jersey, United States". "United States Census, 1940," database with images, FamilySearch; citing enumeration district (ED) 7-221, sheet 14A, family 306, NARA digital publication T627 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2012), roll 2336. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- "Charles L. Goeller". New York Times. 1955-03-08. p. 27.

- Donald E. Wolf (1996). Big Dams and Other Dreams: The Six Companies Story. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 174–175. ISBN 978-0-8061-2853-5.

- "Flying". Flying. Chicago, Ill.: Ziff-Davis. 31 (2): 66. August 1942. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- "Flying". Flying. Chicago, Ill.: Ziff-Davis. 33 (1): 102. July 1943. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- "[Finding Aid:] James M. Shimer Kaiser-Fleetwings papers, 1942-1958". Philadelphia Area Consortium of Special Collections Libraries. Retrieved 2016-05-31.

- "Artist File: Charles Louis Goeller". New York Art Resources Consortium; Frick. Retrieved 2016-06-01.