Chañares Formation

The Chañares Formation is a Carnian-age geologic formation of the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin, located in La Rioja Province, Argentina. It is characterized by drab-colored fine-grained volcaniclastic claystones, siltstones, and sandstones which were deposited in a fluvial to lacustrine environment. The formation is most prominently exposed within Talampaya National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site within La Rioja Province.[2][3][4]

| Chañares Formation Stratigraphic range: Latest Ladinian? - early Carnian ~237–234 Ma | |

|---|---|

| Type | Geologic formation |

| Unit of | Agua de la Peña Group |

| Sub-units | Lower member, Upper member |

| Underlies | Los Rastros Formation |

| Overlies | Tarjados Formation |

| Thickness | ~70 meters[1] |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Claystone, siltstone, sandstone |

| Other | Tuff, conglomerate |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 29.8°S 67.8°W |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 49.9°S 37.8°W |

| Region | La Rioja Province |

| Country | |

| Extent | Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Chañares River |

Chañares Formation (Argentina) | |

The Chañares formation is the lowermost stratigraphic unit of the Agua de la Peña Group, overlying the Tarjados Formation of the Paganzo Group, and underlying the Los Rastros Formation. Though previously considered Ladinian in age, U-Pb dating has determined that most or all of the Chañares Formation dates to the early Carnian stage of the Late Triassic.[5][6]

The Chañares Formation has provided a diverse and well-preserved faunal assemblage which has been studied intensively since the 1960s. The most common reptiles were proterochampsids (Chanaresuchus, Tropidosuchus, and Gualosuchus), which lived alongside true archosaurs such as Lewisuchus, Lagerpeton, Marasuchus, Gracilisuchus, and Luperosuchus. Cynodonts were abundant, represented by the medium-sized traversodontid Massetognathus, as well as smaller carnivores such as Chiniquodon and Probainognathus. The largest animal in the ecosystem was the giant dicynodont Dinodontosaurus.[3] An older faunal assemblage, distinguished by the large erpetosuchid Tarjadia, has been discovered in the earliest part of the formation.[4] The formation as a whole is considered one of the best sources of Carnian-age tetrapods in South Africa, along with the slightly younger Ischigualasto Formation which lies above the Los Rastros Formation.[2][3]

Geology

The Chañares Formation is the lowermost unit of the Agua de la Peña Group, representing the onset of the first syn-rift phase of the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin. It unconformably overlies red fluvial (river) sediments of the Tarjados Formation of the Paganzo Group, and is conformably overlain by greenish lake and delta sediments of the Los Rastros Formation.[2] The Chañares Formation has also had an interesting history with the lower part of the Ischichuca Formation. This sequence of sediments on the western edge of the basin has occasionally been considered to take priority over the Chañares Formation and the lower part of the Los Rastros Formation. However, this is rare due to the historical significance of the Chañares Formation. As a result, some authors restrict the Ischichuca Formation to a few layers of lake and delta sediments between the Chañares and Los Rastros formations, while others reject using it in the first place.[2]

The Chañares formation was originally thought to be deposited during the Ladinian stage of the Middle Triassic. However, Uranium-Lead radiometric dating by Marsicano et al. (2016) later found that a large portion of the formation was deposited in the early Carnian (237–234 Ma), near the start of the Late Triassic.[6] 2020 U-Pb dating of the overlying lower Los Rastros Formation yielded an age of 234.47 ± 0.44 Ma, making the vast majority of the Chañares Formation lowermost Carnian.[7] Nevertheless, the Ladinian-Carnian boundary may still lie within the first few meters of the formation, despite the primary fossiliferous sections being well-supported as early Carnian in age.[4]

The formation is primarily sandstone, siltstone, and claystone, arranged in a specific sequence of facies. A distinct and uneven unconformity separates the base of the Chañares Formation from the underlying Tarjados Formation. In the field, this unconformity can be identified by a high-relief layer of chert at the top of the Tarjados Formation.[2][3][4][8]

Fluvial olive-grey facies

Above this unconformity lies the oldest section of the Chañares Formation, a package of olive-grey fluvial sediments. As one goes up the section, increasingly finer beds of sandstone and siltstone are interlayered with coarser lenses, corresponding to periodic sheet floods along braided rivers. Weakly-developed palaeosols can be found within this section, filled with root traces, pebbles and small brown calcareous nodules.[2][3][1] Winding systems of burrows have also been found in this section, likely created by small cynodonts.[1]

Though fossils are relatively uncommon in the lower fluvial beds of the Chañares Formation, they are taxonomically and taphonomically distinct from those of succeeding layers. The most common remains are from large dicynodonts (possibly referable to Dinodontosaurus), the large erpetosuchid Tarjadia, and small non-massetognathine cynodonts closely related to Aleodon and Scalenodon. This ecosystem has been termed the Tarjadia Assemblage Zone, in order to distinguish it from the slightly younger classic Chañares assemblage. No radiometric dating has been done on this section, but it may contain the Ladinian-Carnian boundary based on dates obtained within the younger facies.[4][1][8]

Fossiliferous bluish facies

Above the olive-grey fluvial beds is the most fossiliferous and well-studied portion of the formation. This section is characterized by wide and massive layers of very fine bluish-grey sandstone, siltstone, and claystone. These layers have a high concentration of volcanic ash and debris, ranging from glassy shards at the base to weathered bentonites at the top.[2][3][4][8] Nearby volcanic eruptions likely impacted the local climate and river systems, shifting the depositional regime from a stable braided fluvial system to one dominated by shallow floodplains and lahars.[3] Marsicano et al. (2016) obtained a CA-TIMS U-Pb age of 236.1 ± 0.6 Ma from a siltstone bed immediately below the first major fossil layer within the bluish facies.[6] Ezcurra et al. (2017) later studied a slightly older sandstone bed using LA-MC-IMP-MS U-Pb dating. They found a date of 236.2 ± 1.1 Ma from a cluster of the three youngest zircons.[4]

The most productive and historically relevant fossil beds of the Chañares Formation lie within these volcaniclastic layers. The layers are replete with massive calcareous concretions, some up to 2 meters in width. They commonly preserve articulated skeletal material, often complete skeletons from multiple taxa in a single concretion. Well-preserved fossils found within concretions typically represent smaller taxa, which were buried rapidly after death.[3] Volcanic catastrophes such as lahars, ash falls, or pyroclastic flows[2] are the preferred cause of these rapid mass mortality events.[3] More fragmentary fossils are also occasionally found outside of concretions, much like fossils of the underlying Tarjadia AZ.[4] Fossils found outside concretions are typically from large animals, and were probably buried more slowly (albeit still fairly rapidly) by gradual processes.[3]

The classic Chañares fauna, recently codified as the Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus Assemblage Zone, is characteristic of this section of the formation.[4][1] The largest components of the ecosystem include dicynodonts (namely Dinodontosaurus) and indeterminate carnivorous paracrocodylomorphs, similar to taxa from the underlying Tarjadia AZ.[3][4] By far the most common fossils belong to three species of cynodonts: Massetognathus pascuali, Probainognathus jenseni, and Chiniquodon theotonicus.These three species comprise nearly 3/4ths of the fossils found in the formation, with almost half of the total fossils in the formation referred to Massetognathus alone. Reptile fossils are less prevalent but more diverse, with the most common belonging to the proterochampsid archosauriform Chanaresuchus. Other notable taxa include Lagerpeton, Lagosuchus, and Lewisuchus, which were among the oldest non-dinosaur dinosauromorphs, as well as the first to be described.[2][3] Several communal latrines are known from the bluish facies, preserving dicynodont coprolites filled with plant remains.[8]

Upper member

The olive-grey fluvial section and the bluish-grey volcaniclastic section collectively form the lower member of the Chañares Formation. They are overlain by an upper member, which is practically devoid of body fossils. The upper member is generally similar to the bluish facies in appearance, with wide beds of fine-grained volcaniclastic sediments with a pale grey color. Unlike the bluish facies, concretions and body fossils are absent, having been replaced by Taenidium worm burrows. These burrows likely indicate that the environment had transitioned into a lacustrine (lake) ecosystem by the time that the upper member was deposited. Some outcrops preserve a few sandstone and conglomerate beds near the top of the upper member. These indicate that the depositional regime continued to shift towards the deltaic environment of the overlying Los Rastros Formation.[2][3][4] The coarser beds also contain a few rare body fossils from fish and tetrapods.[9][4][8] A white tuff near the base of the upper member has been dated to 233.7 ± 0.4 Ma,[6] while a zircon cluster from a sandy tuff at the top of the formation was dated to 233.6 ± 1.1 Ma.[4]

Paleobiota

Plant remains and palynomorphs preserved in the dicynodont coprolites were described in 2018. Though it is difficult to determine the affinities of the larger plant fragments, the palynomorphs are more conclusive. They belong to a broad range of plants, most abundantly pollen from umkomasiales (a type of seed fern), and in smaller portions from podocarpean and voltzialean conifers. Spores from humid-loving groups such as bryophytes, lycopsids, true ferns, and algae were also present but rare. The palynomorph taxa generally resemble those of the Dicroidium flora which is common in other late Ladinian-early Carnian units. More precisely, the flora is intermediate between the temperate Ipswich flora of far southern Gondwana, and the hot, subtropical Onslow flora which developed along the southern shore of the Neotethys. This transitional character is also observed in the flora of the nearby Ischigualasto Formation, as well as the Flagstone Bench Formation of Antarctica. Curiously, the Los Rastros Formation, which was deposited between the Chañares and Ischigualasto Formations, preserves a typical Ipswich flora. This likely indicates that all three formations lie at a latitude which allows them to quickly shift between the different floras during small climatic changes.[8]

Tetrapod burrows, likely produced by small eucynodonts, have been described from the lower section of the formation.[1]

Synapsids

Color key

|

Notes Uncertain or tentative taxa are in small text; |

| Synapsids of the Chañares Formation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Assemblage Zone | Material | Notes | Images |

| cf. Aleodon[4] | Tarjadia AZ | A single partial skull | A small chiniquodontid cynodont | ||

| Chiniquodon | C. theotonicus | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Numerous specimens[3] | A common chiniquodontid cynodont |  |

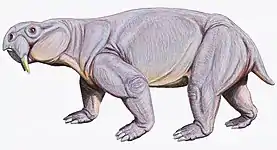

| Dinodontosaurus | D. brevirostris | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Several specimens[3][10] | A large kannemeyeriiform dicynodont | |

| D. platyceps | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Two specimens[3][10] | A massive kannemeyeriiform dicynodont | ||

| D. platygnathus | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | One fragmentary specimen[3][10] | A massive kannemeyeriiform dicynodont | ||

| D. sp. | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Several specimens[3][10] | A massive kannemeyeriiform dicynodont |  | |

| Kannemeyeriiformes indet.[4] | Tarjadia AZ | Several specimens | Indeterminate remains from massive kannemeyeriiform dicynodonts, possibly referrable to Dinodontosaurus | ||

| Massetognathus | M. major | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | A single skull | A junior synonym of Massetognathus pascuali[11] | |

| M. pascuali[12] | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Numerous specimens (almost half of all recovered fossils)[3] | An abundant massetognathine traversodontid cynodont | ||

| M. teruggii[12] | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Several skulls | A junior synonym of Massetognathus pascuali[11] | ||

| Megagomphodon | M. oligodens | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | A pair of skulls | A junior synonym of Massetognathus pascuali[11] | |

| Probainognathus[13] | P. jenseni | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Numerous specimens[3] | A very common probainognathid cynodont |  |

| Probelesodon | P. lewisi[14] | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Numerous specimens | A probable junior synonym of Chiniquodon theotonicus[15] |  |

| P. minor[16] | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Numerous specimens | A probable junior synonym of Probelesodon lewisi or Chiniquodon theotonicus[15] | ||

| cf. Scalenodon/Mandagomphodon[4] | Tarjadia AZ | Two partial jaws | A small basal traversodontid cynodont | ||

| Stahleckeria[17] | S. sp. | Tarjadia AZ | An incomplete ulna | A large stahleckeriine dicynodont |  |

Reptiles

| Reptiles of the Chañares Formation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Assemblage Zone | Material | Notes | Images |

| Chanaresuchus[18] | C. bonapartei | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Several specimens[3] | A fairly common proterochampsid archosauriform | |

| Elorhynchus[19] | E. carrolli | Tarjadia AZ | One specimen | A stenaulorhynchine rhynchosaur | |

| Gracilisuchus[20] | G. stipaniciorum | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Several specimens[3] | A small gracilisuchid pseudosuchian | |

| Gualosuchus[18] | G. reigi | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Two specimens[3] | A rare proterochampsid archosauriform |  |

| Lagerpeton[21] | L. chanarensis | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Several specimens[3] | A small lagerpetid avemetatarsalian. |  |

| Lagosuchus[21] | L. talampayensis | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | One specimen (apart from those referred to Marasuchus) | A small bipedal dinosauriform. Original specimen may be indeterminate[22] or valid[23] |  |

| Lewisuchus[24] | L. admixtus | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Several specimens, including two with cranial material.[25][26] | A silesaurid dinosauriform[25] |  |

| Luperosuchus[27] | L. fractus | Tarjadia AZ[4] | A partial skull | A large predatory loricatan pseudosuchian |  |

| Marasuchus[22] | M. lilloensis[28] | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Several specimens[3] | A small bipedal dinosauriform, originally described as a species of Lagosuchus. May be a junior synonym of Lagosuchus talampayensis[23] |  |

| Paracrocodylomorpha indet. | Tarjadia AZ,[4] Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ[3] | Several specimens | Medium-sized to very large indeterminate paracrocodylomorphs | ||

| Pseudolagosuchus | P. major | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Several specimens | A junior synonym of Lewisuchus admixtus[26] | |

| Rhadinosuchinae indet. | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | A pair of partial skeletons, one of which including a skull | Indeterminate rhadinosuchine proterochampsids showing a combination of features from previously-known rhadinosuchine species such as Chanaresuchus, Gualosuchus, and Rhadinosuchus[29] | ||

| Stenaulorhynchinae indet.[4] | Tarjadia AZ[4] | A few tooth plates and jaw fragments[30][4] | Indeterminate stenaulorhynchine rhynchosaurs, likely synonymous with Elorhynchus[19] | ||

| Tarjadia | T. ruthae | Tarjadia AZ[4] | Several specimens | A large predatory erpetosuchid[4] | |

| Tropidosuchus | T. romeri | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ | Several specimens[3] | A fairly common proterochampsid archosauriform | |

Fish

| Fish of the Chañares Formation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxon | Assemblage Zone | Material | Notes | Images |

| Mawsoniidae indet. | Massetognathus-Chanaresuchus AZ (lower member of the formation) | Skull fragment | An indeterminate mawsoniid coelacanth[9] | |

| cf. Pseudobeaconiidae | Upper member of the formation | Scale patches | An indeterminate pseudobeaconiid perleidiform[9] | |

References

- Fiorelli et al., 2018

- Rogers et al., 2001

- Mancuso et al., 2014

- Ezcurra et al., 2017

- Kent et al, 2014, p.7959

- Marsicano et al., 2016

- Mancuso et al., 2020

- Pérez et al., 2018

- Gouiric-cavalli et al., 2017

- de los Angeles Ordonez et al., 2020

- Abdala & Giannini, 2000

- Romer, 1967, III

- Romer, 1971, VI

- Romer, 1971, V

- Abdala & Giannini, 2002

- Romer, 1971, XVIII

- Mancuso & Irmis, 2019

- Romer, 1971, XI

- Ezcurra et al., 2021

- Romer, 1972, XIII

- Romer, 1972, X

- Sereno & Arcucci, 1994

- Agnolin & Ezcurra, 2019

- Romer, 1972, XIV

- Bittencourt, 2014

- Ezcurra et al., 2019 (Lewisuchus)

- Romer, 1971, VIII

- Romer, 1972, XV

- Ezcurra et al., 2019 (Rhadinosuchines)

- Ezcurra et al., 2014

Bibliography

- Ezcurra, Martin D.; Lucas E. Fiorelli; M. Jimena Trotteyn; Agustín G. Martinelli, and Julia M. Desojo. 2021. The rhynchosaur record, including a new stenaulorhynchine taxon, from the Chañares Formation (upper Ladinian–?lowermost Carnian levels) of La Rioja Province, north-western Argentina. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology in press. .

- de los Angeles Ordoñez, María; Claudia A. Mariscano, and Adriana C. Mancuso. 2020. New specimen of Dinodontosaurus (Therapsida, Anomodontia) from west-central Argentina (Chañares Formation) and a reassessment of the Triassic Dinodontosaurus Assemblage Zone of southern South America. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 100. .

- Mancuso, Adriana C.; Cecilia A. Benavente; Randall B. Irmis, and Roland Mundil. 2020. Evidence for the Carnian Pluvial Episode in Gondwana: New multiproxy climate records and their bearing on early dinosaur diversification. Gondwana Research in press. . doi:10.1016/j.gr.2020.05.009

- Lecuona, Agustina; Julia Brenda Desojo, and Ignacio Alejandro Cerda. 2020. New information on the anatomy and histology of Gracilisuchus stipanicicorum (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia) from the Chañares Formation (early Carnian), Argentina. Comptes Rendus Palevol 19. 40–62. Accessed 2020-09-01.

- Mancuso, Adriana C., and Randall B. Irmis. 2019. The Large-Bodied Dicynodont Stahleckeria (Synapsida, Anomodontia) from the Upper Triassic (Carnian) Chañares Formation (Argentina); New Data for Triassic Gondwanan Biogeography. Ameghiniana 57. 45-57.

- Ezcurra, Martin D.; M. Belén Von Baczko; M. Jimena Trotteyn, and Julia M. Desojo. 2019. New Proterochampsid Specimens Expand the Morphological Diversity of the Rhadinosuchines of the Chañares Formation (Lower Carnian, Northwestern Argentina). Ameghiniana 56. 79-115.

- Agnolin, Federico L., and Martin D. Ezcurra. 2019. THE VALIDITY OF LAGOSUCHUS TALAMPAYENSIS ROMER, 1971 (ARCHOSAURIA, DINOSAURIFORMES), FROM THE LATE TRIASSIC OF ARGENTINA. Breviora 565. 1–21.

- Ezcurra, Martín D.; Sterling J. Nesbitt; Lucas E. Fiorelli, and Julia B. Desojo. 2019. New specimen sheds light on the anatomy and taxonomy of the early Late Triassic dinosauriforms from the Chañares Formation, NW Argentina. The Anatomical Record 303. 1393-1438.

- Fiorelli, Lucas E.; Sebastián Rocher; Agustín G. Martinelli; Martín D. Ezcurra; E. Martín Hechenleitner, and Miguel Ezpeleta. 2018. Tetrapod burrows from the Middle–Upper Triassic Chañares Formation (La Rioja, Argentina) and its palaeoecological implications. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 496. 85–102. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Pérez Loinaze, Valeria Susana; Ezequiel Ignacio Vera; Lucas Ernesto Fiorelli, and Julia Brenda Desojo. 2018. Palaeobotany and palynology of coprolites from the Late Triassic Chañares Formation of Argentina: implications for vegetation provinces and the diet of dicynodonts. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 502. 31–51. Accessed 2018-09-08.

- Ezcurra, Martín D.; Lucas E. Fiorelli; Agustín G. Martinelli; Sebastián Rocher; M. Belén von Baczko; Miguel Ezpeleta; Jeremías R. A. Taborda; E. Martín Hechenleitner, and M. Jimena Trotteyn. 2017. Deep faunistic turnovers preceded the rise of dinosaurs in southwestern Pangaea. Nature Ecology & Evolution 1. 1477–1483.

- Gouiric-cavalli, Soledad; Julia Brenda Desojo; Martin Daniel Ezcurra; Lucas Ernesto Fiorelli, and Agustin Guillermo Martinelli. 2016. First Fish Remains from the Earliest Late Triassic of the Chañares Formation (La Rioja, Argentina) and Their Paleobiogeographic Implications. Ameghiniana 54. 137-150.

- Marsicano, Claudia A.; Randall B. Irmis; Adriana C. Mancuso; Roland Mundil, and Farid Chemale. 2016. The precise temporal calibration of dinosaur origins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113. 509–513. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Mancuso, Adriana; Leandro Gaetono; Juan Leardi; Fernando Abdala, and Andrea Arcucci. 2014. The Chañares Formation: a window to a Middle Triassic ~ tetrapod community. Lethaia 47. 244–265. Accessed .

- Bittencourt, Jonathas S.; Andrea B. Arcucci; Claudia A. Marsicano, and Max C. Langer. 2014. Osteology of the Middle Triassic archosaur Lewisuchus admixtus Romer (Chañares Formation, Argentina), its inclusivity, and relationships amongst early dinosauromorphs. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology _. 1–31. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Kent, Dennis V.; Paula Santi Malnis; Carina E. Colombi; Oscar A. Alcober, and Ricardo N. Martínez. 2014. Age constraints on the dispersal of dinosaurs in the Late Triassic from magnetochronology of the Los Colorados Formation (Argentina). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111. 7958–7963. Accessed 2018-09-08.

- Ezcurra, Martín D.; M. Jimena Trotteyn; Lucas E Fiorelli; M. Belén von Baczko; Jeremías R. A. Taborda; Maximiliano Iberlucea, and Julia B. Desojo. 2013. The oldest rhynchosaur from Argentina: a Middle Triassic rhynchosaurid from the Chañares Formation (Ischigualasto–Villa Unión Basin, La Rioja Province). Paläontologische Zeitschrift 88. 456-460.

- Abdala, Fernando, and Norberto Giannini. 2002. Chiniquodontid cynodonts: systematic and morphometric considerations. Palaeontology 45. 1151–1170.

- Rogers, R.R.; A.B. Arcucci; F. Abdala; P.C. Sereno; C.A. Forster, and C.L. May. 2001. Paleoenvironment and taphonomy of the Chañares Formation tetrapod assemblage (Middle Triassic), northwestern Argentina: spectacular preservation in volcanogenic concretions. Palaios 16. 461–481. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Abdala, Fernando, and Norberto Giannini. 2000. Gomphodont Cynodonts of the Chañares Formation: The Analysis of an Ontogenetic Sequence. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20. 501–506.

- Arcucci, A., and C.A. Marsicano. 1999. A distinctive new archosaur from the Middle Triassic (Los Chañares Formation) of Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 19. 228–232. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Sereno, P.C., and A.B. Arcucci. 1994. Dinosaurian precursors from the Middle Triassic of Argentina: Marasuchus lilloensis, gen. nov. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 14. 53–73. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Arcucci, A.B. 1987. Un nuevo Lagosuchidae (Thecodontia-Pseudosuchia) de la fauna de Los Chañares (Edad Reptil Chañarense, Triasico Medio), La Rioja, Argentina. Ameghiniana 24. 89–94. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- The Chañares Triassic reptile fauna

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1973. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XX. Summary. Breviora 413. 1–20. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood, and Arnold D. Lewis. 1973. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XIX. Postcranial materials of the cynodonts Probelesodon and Probainognathus. Breviora 407. 1–26. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1973. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XVIII. Probelesodon minor, a new species of carnivorous cynodont; family Probainognathidae nov. Breviora 401. 1–4. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XVII. The Chañares gomphodonts. Breviora 396. 1–9. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XVI. Thecodont classification. Breviora 395. 1–15. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XV. Further remains of the thecodonts Lagerpeton and Lagosuchus. Breviora 394. 1–7.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XIV. Lewisuchus admixtus, gen. et sp. nov., a further thecodont from the Chañares beds. Breviora 390. 1–13. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XIII. An early ornithosuchid pseudosuchian, Gracilisuchus stipanicicorum, gen. et sp. nov. Breviora 389. 1–8. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XII. The postcranial skeleton of the thecodont Chanaresuchus. Breviora 385. 1–21. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XI. Two new long-snouted thecodonts, Chanaresuchus and Gualosuchus. Breviora 379. 1–22. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. X. Two new but incompletely known long-limbed pseudosuchians. Breviora 378. 1–8. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. IX. The Chanares Formation. Breviora 377. 1–8. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. VIII. A fragmentary skull of a large thecodont, Luperosuchus fractus. Breviora 373. 1–8. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Jenkins, Farish A. 1970. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. VII. The postcranial skeleton of the traversodontid Massetognathus pascuali (Therapsida, Cynodontia). Breviora 352. 1–28. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1970. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. VI. A chiniquodontid cynodont with an incipient squamosal-dentary jaw articulation. Breviora 344. 1–18. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1969. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. V. A new chiniquodontid cynodont, Probelesodon lewisi - cynodont ancestry. Breviora 333. 1–24. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1968. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. IV. The dicynodont fauna. Breviora 295. 1–25. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1967. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. III. Two new gomphodonts, Massetognathus pascuali and M. teruggii. Breviora 264. 1–25. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1966. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. II. Sketch of the geology of the Rio Chañares-Rio Gualo region. Breviora 252. 1–20. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood. 1966. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. I. Introduction. Breviora 247. 1–14. Accessed 2019-03-28.