Cerebellar degeneration

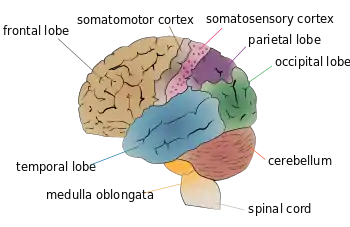

Cerebellar degeneration is a condition in which cerebellar cells, otherwise known as neurons, become damaged and progressively weaken in the cerebellum.[1] There are two types of cerebellar degeneration; paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration, and alcoholic or nutritional cerebellar degeneration.[2] As the cerebellum contributes to the coordination and regulation of motor activities, as well as controlling equilibrium of the human body, any degeneration to this part of the organ can be life-threatening. Cerebellar degeneration can result in disorders in fine movement, posture, and motor learning in humans, due to a disturbance of the vestibular system. This condition may not only cause cerebellar damage on a temporary or permanent basis, but can also affect other tissues of the central nervous system, those including the cerebral cortex, spinal cord and the brainstem (made up of the medulla oblongata, midbrain, and pons).[2]

| Cerebellar degeneration | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cerebellum (labeled bottom right) of the human brain. It is located above the brain stem, posterior to the brain. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Cerebellar degeneration can be attributed to a plethora of hereditary and non-hereditary conditions. More commonly, cerebellar degeneration can also be classified according to conditions that an individual may acquire during their lifetime, including infectious, metabolic, autoimmune, paraneoplastic, nutritional or toxic triggers.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Patients suffering from cerebellar degeneration experience a progressive loss of nerve cells (Purkinje cells) throughout the cerebellum. As well as this, it is common to incur an elevated blood protein level and a high volume of lymph cells within the cerebrospinal fluid, resulting in swelling and enlargement of the brain. The most characteristic signs and symptoms experienced by patients with cerebellar degeneration include:[2][4]

- muscle weakness

- an uncoordinated, staggering walk

- quivering of the torso

- jerky arm and leg movements

- tendency to falling over

- dysarthria (difficulty in articulating speech)

- dysphagia (difficulty in deglutition/swallowing of solids and liquids)

- vertigo (dizziness)

- nystagmus (rapid, involuntary eye movements), causing sleep disturbances

- ophthalmoplegia (paralysis of extraocular muscles)

- diplopia (double vision)

Scientific studies have revealed that psychiatric symptoms are also common in patients with cerebellar degeneration,[5][6] where dementia is a typical psychiatric disorder resulting from cerebellar damage. Approximately 50% of all patients suffer from dementia as a result of paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration.[2]

Causes

The root cause of incurring a cerebellar degenerative condition can be due to a range of different inherited or acquired (non-genetic and non-inherited) conditions, including neurological diseases, paraneoplastic disorders, nutritional deficiency, and chronic alcohol abuse.[7]

Neurological diseases

A neurological disease refers to any ailment of the central nervous system, including abnormalities of the brain, spinal cord and other connecting nerve fibres.[8] Where millions of people are affected by neurological diseases on a worldwide scale,[9] it has been identified that the number of different types of neurological diseases exceeds six hundred,[10] any of which an individual can incur. Some of the most prevalent types include Alzheimer's disease, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, Parkinson's disease and stroke.[11] More specifically, the neurological diseases that can cause cerebellar degeneration include:[12]

Inherited

- Spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA), which refers to a group of conditions caused by mutations in the genes of a human, and are characterised by degenerative changes to many parts of the central nervous system, inclusive of the cerebellum, brain stem, and spinal cord.[13] If a parent is affected by SCA, each of their children will have a 50% risk of inheriting the mutated gene.[13]

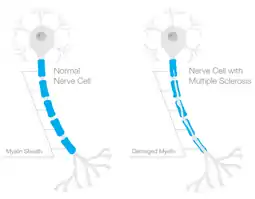

- Multiple sclerosis (MS), a progressive and incurable condition caused by the combination of an individual's genetic influences and environmental circumstances.[4] It occurs when the myelin sheath of the nerve cells becomes damaged.[14] As the myelin sheath is responsible for protecting the nerves and conducting rapid impulses between them, any damage to this lipid-rich layer will result in delayed and interrupted nerve impulses to and from the brain.[15]

Non-inherited

- Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), which refers to a combination of diseases caused by the subsistence of foreign proteins in the blood, called prions.[16] Prions originate in the bloodstream via ingestion of contaminated foods or through contact with contaminated medical instruments, body fluids, or infected tissue. This causes severe inflammation of the brain, impairing one's memory, personality and muscular coordination.

- Acute & haemorrhagic stroke, resulting in the death of neurons in the cerebellum due to a disrupted flow of oxygen to the brain.[17] This disrupted flow may be due to one of two causes; either a narrowing or blocked artery which derives from a build-up of plaque in the inner walls of the coronary arteries, or a ruptured blood vessel, commonly deriving from high blood pressure or head trauma.[18]

Paraneoplastic disorders

Paraneoplastic disorders are a combination of non-inherited conditions that are activated by an individual's autoimmune response to a malignant tumour. These disorders prevail when T-cells (also known as white blood cells) begin to harm familiar cells in the central nervous system rather than the cancerous cells,[2] resulting in degeneration of neurons in the cerebellum. Other signs and symptoms that commonly result from the incursion of a paraneoplastic disorder include an impaired ability to talk, walk, sleep, maintain balance and coordinate muscle activity, as well as experiencing seizures and hallucinations.[19] Paraneoplastic disorders are prevalent among middle-aged individuals, typically those suffering from lung, lymphatic, ovarian or breast cancer.[20]

Nutritional deficiency

Nutritional deficiency relates to an insufficient amount of macronutrients and micronutrients being provided to the body. Nutrient deficiencies are most prevalent among infants, the elderly, the poverty-stricken, and individuals with eating disorders.[21] Chronic alcohol abuse is the diagnosis of which an individual frequently consumes excessive amounts of alcohol, and thus becomes dependent on the intoxicating substance. Studies show that men of every age group consume more alcohol than women, where the prevalence is higher in some regions of the world than others, such as across Western Europe and Australia.[22][23] Both nutritional deficiency and chronic alcohol abuse are non-inherited conditions that lead to impaired absorption or utilisation of the vitamin thiamine (B-1) by the body, thus causing temporary or permanent damage to cerebellar cells.[2] Alcoholic degeneration of cerebellar cells is the most common trigger of spinocerebellar ataxia.[24]

Diagnosis

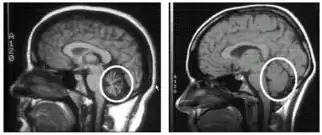

To select an appropriate and accurate diagnostic test for cerebellar degeneration, it is crucial that a range of factors specific to each patient are taken into consideration. These include; the patient's age, acuity of their signs and symptoms, associated neurological conditions, and family history of hereditary forms of cerebellar degeneration.[3] A diagnosis for cerebellar degeneration is regarded after any of the aforementioned signs and symptoms surface. For genetically-classified forms of cerebellar degeneration, genetic testing can be carried out in order to confirm or deny the diagnosis, where this form of testing is only possible if the gene responsible for the cause of the condition is recognised.[25] In saying this, for most conditions the genetic cause of cerebellar degeneration is unidentified, hence these patients cannot proceed with genetic testing.[1] In cases where cerebellar degeneration is acquired, a diagnosis can be established using imaging methods such as computerised tomography (CT scans) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), necessary to detect brain abnormalities in patients suffering from cerebellar degeneration.[26]

Treatment

Like any other disease, treatment for cerebellar degeneration is contingent on the underlying cause, unique to each patient. As of present time, hereditary forms of cerebellar degeneration are incurable, though they can be managed. Management is centred around coping with symptoms and improving a patient's quality of life. In these cases, immediate management of inherited cerebellum damage should involve consultation with a neurologist, followed by specific management approaches based on the signs and symptoms experienced by each unique patient.[3] These management approaches aim to provide supportive care to the patient, consisting of physical therapy to strengthen muscles, occupational therapy, and speech pathology. Long-term management of inherited cerebellar degeneration involves an ongoing commitment to supportive care therapies, as well as a longitudinal relationship with a neurologist. In some instances adjustments need to be made in the patients home, to improve accessibility and mobility in and around their living environment, to optimise safety.[3]

For non-hereditary types of cerebellar degeneration, some physical and mental indicators can be reversed by treating the fundamental cause.[27] For instance, the signs and symptoms of paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration can be managed by initially terminating the underlying cancer with treatments such as surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. In cases of nutritional or alcoholic cerebellar degeneration, symptoms of these conditions can be relieved by initially consuming a balanced diet and discontinuing the consumption of alcohol respectively, followed by dietary supplementation with thiamine.[2]

Prognosis

The long-term prospect for patients suffering from cerebellar degeneration differs according to the underlying cause of the disease.[1] Each inherited or acquired disease that results in cerebellar degeneration has its own specific prognosis, however most are generally poor, progressive and often fatal.[3]

Epidemiology

Cerebellar degeneration continues to carry a considerable burden on the health of the world population, as well as on health agencies and governing bodies across the globe. Cerebellum-related disorders generally transpire in individuals between the ages of 45 to 65 years, however the age of symptomatic onset differs in accordance with the underlying cause of the degenerative disorder.[1] For paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration, the average age of onset is 50 years, generally affecting a greater population of males than females.[2] Nutritional and alcoholic cerebellar degeneration, being more prevalent than paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration, affects individuals with a thiamine deficiency and dipsomaniacs, respectively.[2] Recent epidemiological studies on cerebellar degeneration estimated a global prevalence rate of 26 per 100,000 cases of cerebellar degeneration in children.[28]

References

- "Cerebellar degeneration". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- "Cerebellar Degeneration, Subacute". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- "Cerebellar degeneration". Clinical Advisor. 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- "Cerebellar degeneration". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- Liszewski CM, O'Hearn E, Leroi I, Gourley L, Ross CA, Margolis RL (February 2004). "Cognitive impairment and psychiatric symptoms in 133 patients with diseases associated with cerebellar degeneration". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 16 (1): 109–12. doi:10.1176/jnp.16.1.109. PMID 14990766.

- Phillips JR, Hewedi DH, Eissa AM, Moustafa AA (2015). "The cerebellum and psychiatric disorders". Frontiers in Public Health. 3: 66. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2015.00066. PMC 4419550. PMID 26000269.

- Agamanolis D. "Ataxia and cerebellar degeneration". neuropathology-web.org. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- Liszewski CM, O'Hearn E, Leroi I, Gourley L, Ross CA, Margolis RL (2004). "Cognitive impairment and psychiatric symptoms in 133 patients with diseases associated with cerebellar degeneration". J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 16: 109–12. doi:10.1176/jnp.16.1.109. PMID 14990766..

- Liszewski CM, O'Hearn E, Leroi I, Gourley L, Ross CA, Margolis RL (2004). "Cognitive impairment and psychiatric symptoms in 133 patients with diseases associated with cerebellar degeneration". J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 16: 109–12. doi:10.1176/jnp.16.1.109. PMID 14990766..

- Phillips JR, Hewedi DH, Eissa AM, Moustafa AA (2015). "The cerebellum and psychiatric disorders". Front Public Health. 3: 66. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2015.00066. PMC 4419550. PMID 26000269..

- Agamanolis D. "Ataxia and cerebellar degeneration". neuropathology-web.org. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- "Spinocerebellar ataxia". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- "Spinocerebellar ataxia". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- "Multiple sclerosis (MS)". Australian Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- "Myelin Sheath - Definition and Function | Biology Dictionary". Biology Dictionary. 2017-02-10. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- "Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies (TSEs)". European Food Safety Authority. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- "About Stroke". Stroke Foundation - Australia. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- "Stroke - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- "Paraneoplastic syndromes of the nervous system - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- "Paraneoplastic Neurologic Disorders | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- "Nutritional Deficiencies". www.clinicaladvisor.com. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- "Alcohol consumption". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Vogeltanz-Holm ND, Gmel G (September 2009). "Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS project". Addiction. 104 (9): 1487–500. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02696.x. PMC 2844334. PMID 19686518.

- Shanmugarajah PD, Hoggard N, Currie S, Aeschlimann DP, Aeschlimann PC, Gleeson DC, Karajeh M, Woodroofe N, Grünewald RA, Hadjivassiliou M (2016-10-03). "Alcohol-related cerebellar degeneration: not all down to toxicity?". Cerebellum & Ataxias. 3 (1): 17. doi:10.1186/s40673-016-0055-1. PMC 5048453. PMID 27729985.

- "Autosomal Dominant Hereditary Ataxia". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- "Cerebellar Disorders - Neurologic Disorders". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- Salman MS (February 2018). "Epidemiology of Cerebellar Diseases and Therapeutic Approaches". Cerebellum. 17 (1): 4–11. doi:10.1007/s12311-017-0885-2. PMID 28940047. S2CID 46763077.