Central Asians in Ancient Indian literature

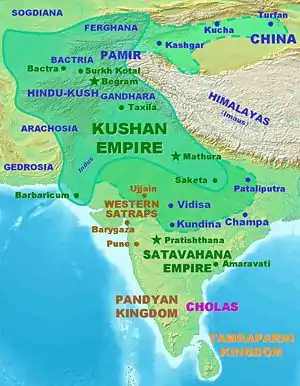

Central Asia and Ancient India have long traditions of social-cultural, religious, political and economic contact since remote antiquity.[1] The two regions have common and contiguous borders, climatic continuity, similar geographical features and geo-cultural affinity. But the flow of people and the impact on native population and its archaeogenetics have been negligible throughout the thousands of years of contact.

Migrations

In classical Indian tradition clans of the Shakas, Yavanas, Kambojas, Pahlavas, Paradas and others are also attested to have been coming as invaders and that they were all finally absorbed into the community of Kshatriyas.[2]

Chinese author Ma-twan-lin writes that, "The nomenclature of the early Sakas in India shows an admixture of Scythian, Parthian and Iranian elements. In India the Scythians soon adapted themselves to their new environs and began to adopt Indian names and religious beliefs."[3]

Central Asian people in ancient Indian literature

Atharvaveda

Atharvaveda refers to Gandhari, Mujavat and Bahlika from the north-west (Central Asia). Gandharis are Gandharas, the Bahlikas are Bactrians, Mujavat (land of Soma) refer to Hindukush–Pamirs (the Kamboja region) and possibly be the Muztagh Ata mountain.[4]

The post-Vedic Atharvaveda-Parisista (Ed Bolling & Negelein) makes first direct reference to the Kambojas (verse 57.2.5). It also juxtaposes the Kambojas, Bahlikas and Gandharas.[5]

Sama Veda

The Vamsa Brahmana of the Sama Veda refers to Madrakara Shaungayani as the teacher of Aupamanyava Kamboja. Sage Shangayani Madrakara, as his name itself shows, and as the scholars have rightly pointed out, belonged to the Madra people.

Prof Jean Przylusky has shown that Bahlika (Balkh) was an Iranian settlement of the Madras who were known as Bahlika-Uttaramadras i.e. the northern Madras, living in Bahlika or Bactria country. These Bahlika Uttara Madras are the Uttara Madras of the Aitareya Brahamana.

This connection between the Uttara Madras and the Kambojas is said to be natural because they were close neighbours in the north-west.[6]

Manusmriti

Manusmriti asserts that the Kambojas, Sakas, Yavanas, Paradas, Pahlavas, etc., had been Kshatriyas of good birth but were gradually degraded to the barbaric status due to their not following the Brahmanas and the Brahmanical code of conduct.

The Silk road route through which erstwhile Hindu Vedic societies became partially Buddhists as well as the Hindu names and history of these kingdoms lend credence to this idea. Furthermore, almost invariably, the royal clans of Central Asia and Northwestern India claimed descent from historical Hindu royalties and royal lines such as Suryavanshi and Chandravanshi. Many of these kings and nobilities often claimed direct descent from Lord Rama and Pandavas to strengthen their claim to throne.[7]

Puranas

The Haihaya Yadavas are the first known invaders in the recorded history of the sub-continent. Described in the Puranas as allying with four other groups, the invaders were eventually defeated and assimilated into the local community under different castes from Kshatriyas to Shudras.[8] Alberuni refers to this description, saying that the "five hordes" belonged to his own people, i.e. Central Asia.[9]

The Puranic Bhuvanakosha attests that Bahlika or Bactria was the northernmost Puranic Janapada of ancient India and was located in Udichya or Uttarapatha division of Indian sub-continent.[10] The Uttarapatha or northern division of Jambudvipa comprised an area of Central Asia from the Urals and the Caspian Sea to the Yenisei and from Turkistan and Tien Shan ranges to the Arctic (Dr S. M. Ali).

Kavyamimamsa of Rajashekhara

The 10th century CE Kavyamimamsa of Pandit Rajashekhara knows about the existence of several Central Asian tribes. He furnishes an exhaustive list of the extant tribes of his times and places the Shakas, Tusharas, Vokanas, Hunas, Kambojas, Vahlika, Vahlava, Tangana, Limpaka, Turushka and others together, styling them all as the tribes from Uttarapatha or north division.[11]

See also

References

- Alberuni's India, 2001, p 19-21, Edward C. Sachau - History; Dates of the Buddha, 1987, p 126, Shriram Sathe; Foundations of Indian Culture, 1984, p 20 sqq, Dr Govind Chandra Pande - History; India & Russia: Linguistic & Cultural Affinity, 1982, Weer Rajendra Rishi; Geographical and Economic Studies in the Mahābhārata: Upāyana Parva, 1945, Dr Moti Chandra - India; Linguistic & Cultural Affinity, 1982, Weer Rajendra Rishi; Racial Affinities of Early North Indian Tribes 1973, Myths of the Dog-Man, 1991, David Gordon White - Social Science; Sudhakar Chattopadhyaya - Ethnic Groups.

- History and Culture of Indian People, The Vedic Age, pp 286-87, 313-14.

- Social and Cultural History of Ancient India, Manilal Bose, p.26

- Witzel, Michael (2012). "Vedic Gods (Indra, Agni, Rudra, Varuṇa, etc.)". Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Brill.

- AV-Par, 57.2.5; cf Persica-9, 1980, p 106, Dr Michael Witzel.

- Vedic Index, 138

- Cultural Heritage of India, I, p 612.

- "The Hindu : Harappa and Vedic Civilisation". www.hindu.com.

- Alberuni's India, Trans. Sachau, p 20-21.

- Kirfel's list of the Uttarapatha countries of Bhuvanakosa.

- Kavyamimamsa Ed. Gaekwad's Oriental Series, I (1916) Chapter 17; Introd., xxvi. Rajashekhara is dated c 880 AD - 920 AD.

Books and periodicals

- Ancient Kamboja, People and the Country, 1981, Dr Kamboj

- Political History of Ancient India, 1996, Dr H. C. Raychaudhury

- India and Central Asia, 1955, Dr P. C., Bagchi.