Catha (mythology)

Catha (Cavatha, Cavtha, Cath, Cautha, and Kavtha) is a female Etruscan lunar or solar deity, who may also be connected to childbirth, and has a connection to the underworld.[1][2] Catha is also the goddess of the south sanctuary at Pyrgi, Italy[1] She is often seen with the Etruscan god Śuri with whom she shares a cult.[3] Catha is also frequently paired with the Etruscan god Fufluns, who is the counterpart to the Greek god Dionysus, and Pacha, the counterpart to the Roman god Bacchus.[4] Additionally, at Pyrgi, Catha is linked with the god Aplu, the counterpart to the Greek god Apollo.[5] Aplu may have even taken some of the characteristics of Catha when he was brought into the Etruscan religion.[5] Giovanni Colonna has suggested that Catha is linked to the Greek Persephone since he links Catha's consort, Suri, to Dis Pater in Roman mythology.[6]

Inscriptions

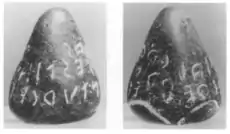

The bulk of information regarding Catha comes mostly from inscriptions on Etruscan artifacts. One example that shows the importance of Catha at Pyrgi is the discovery of gold earrings dating from 530 to 520 BCE which were dedicated to Catha.[7] The Sarcophagus of Laris Pulenas from the third century BCE from Tarquinia has an epitaph stating that the deceased individual was a priest of Catha amongst many other titles.[8] Catha is named on the Piacenza Liver on the right lobe where the gods of the lights and heavens are listed.[9] This suggests that Catha was a cult deity. On some inscriptions, Catha is simply referred to as "daughter", and in Martianus Capella she is referred to as "the Daughter of the Sun".[10] She has also been called the "Eye of the Sun".[11] This evidence, along with her placement on the Piacenza Liver over Usil, suggests that she may be the counterpart to the Roman Solis Filia; however Solis Filia does not have the underworld connection that Catha does.[12] Catha's underworld connections can be best seen on an Attic skyphos from a necropolis in San Cerbone dating to the 5th century BCE with an inscription stating it is dedicated to Catha.[13]

Images

Although there are no known labeled images of Catha, Nancy de Grummond has argued that there are a number of depictions of Catha in art. She has stated that there are several kraters that show a deity that could be identified as Catha.[14] One example that she cites is a krater from Asciano from 350-300 BCE that shows a deity beside two horses instead of four; a sign that they are there to take the dead to the afterlife, and this coupled with the other imagery on the krater suggests that this has an underworld aspect which Catha is associated with.[14] Another potential image of Catha is a figure on an antefix on the twenty-celled building on Pyrgi who is again depicted with two horses.[15] This claim is supported by the fact that this antefix is paired with another antefix that depicts a solar divinity who is likely Śuri, the consort of Catha.[16] A terracotta head discovered at Pyrgi from the fourth century BCE could also potentially a representation of Catha since she was a highly important goddess in the city.[17]

Debates

Nancy de Grummond has also argued that Catha could be a lunar divinity as opposed to a solar divinity. She points out that just because Catha is called the "Daughter of the Sun" does not necessarily mean that she is a solar goddess because Selene, the moon goddess in Greek mythology, is sometimes referred to as the daughter of the Sun as well.[11] Some kraters that potentially illustrate Catha show the deity as having an ambiguous gender which is consistent with Greek, Roman, and Egyptian mythologies.[18] Luna and Selene of Roman and Greek mythology, respectively, are shown driving two-horse chariots often in art.[18] De Grummond has also suggested that since Śuri is a solar god and his consort is Catha, it would make logical sense for his partner to be lunar as opposed to another solar divinity.[19]

References

- Haynes 2000, p. 183.

- de Grummond 2008, p. 419.

- Simon 2006, p. 7.

- Bonfante 2006, p. 13, 19.

- Jannot 2005, p. 146.

- de Grummond 2004, p. 359.

- Colonna 2006, p. 148-149.

- Bonfante 2006, p. 13.

- Bonfante 2006, p. 11.

- Simon 2006, p. 57.

- de Grummond 2008, p. 422.

- de Grummond 2004, p. 361.

- de Grummond 2004, p. 360.

- de Grummond 2008, p. 422-423.

- de Grummond 2008, p. 423-425.

- de Grummond 2008, p. 424-425.

- de Grummond 2008, p. 427.

- de Grummond 2008, p. 423.

- de Grummond 2008, p. 422, 425.

Bibliography

- Bonfante, L (2006). "Etruscan Inscriptions and Etruscan Religion". In de Grummond, NT; Simon, E (eds.). The Religion of the Etruscans. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292782334.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Colonna, G (2006). "Sacred Architecture and the Religion of the Etruscans". In de Grummond, NT; Simon, E (eds.). The Religion of the Etruscans. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292782334.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- de Grummond, NT (2004). "For the Mother and for the Daughter: Some Thoughts on Dedications from Etruria and Praeneste". Hesperia Supplements (33): 351–370.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- de Grummond, NT (2008). "Moon Over Pyrgi: Catha, an Etruscan Lunar Goddess?". American Journal of Archaeology. 112 (3): 419–428.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haynes, S (2000). Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History. Getty Publications. ISBN 9780892366002.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jannot, J (2005). Religion in Ancient Etruria. Translated by J.K. Whitehead. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299208448.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simon, E (2006). "Gods in Harmony: The Etruscan Pantheon". In de Grummond, NT; Simon, E (eds.). The Religion of the Etruscans. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292782334.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- De Grummond, Nancy T. "Moon over Pyrgi: Catha, an Etruscan Lunar Goddess?" American Journal of Archaeology 112, no. 3 (2008): 419-28. Accessed May 10, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/20627480.

External links

Media related to Catha (mythology) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Catha (mythology) at Wikimedia Commons